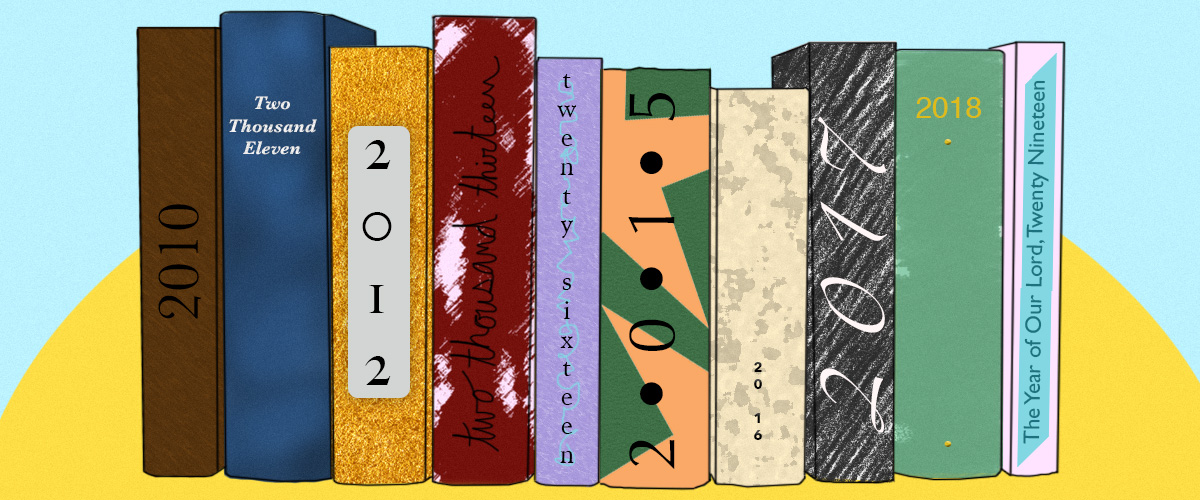

100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (2010)

The novel is dead. Long live the anti-novel, built from scraps.

*

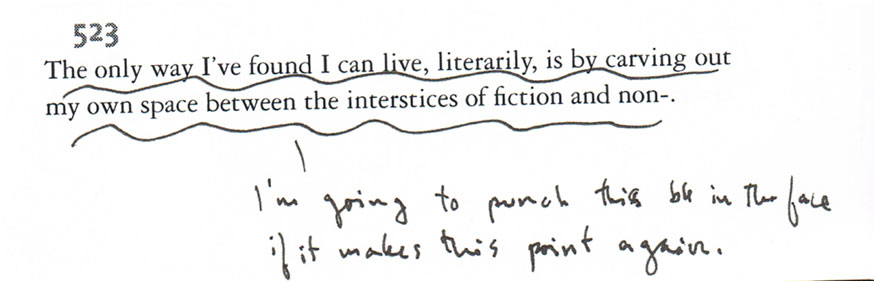

Essential stats: 618 numbered sections, 26 chapters, including “hundreds of quotations that go unacknowledged in the body of the text.” These are acknowledged only at the end of the book, in the 15-page appendix, at the behest of Random House’s lawyers, though Shields begs the reader to cut this out with “a sharp pair of scissors or a razor blade or box cutter” or at the very least not to read them. Oh and also, innumerable think pieces and counter-arguments and exhausting discourse of varying levels of intensity and intelligence.

What was it all about? Basically that remix culture, collage, plagiarism, intertextuality, and genre-blending (especially between fictional and nonfictional forms) and was our generation’s way of seeking a sense of “reality” in art. Or as Shields himself put it in the beginning of this book:

My intent is to write the ars poetica for a burgeoning group of interrelated (but unconnected) artists in a multitude of forms and media (lyric essay, prose poem, collage novel, visual art, film, television, radio, performance art, rap, stand-up comedy, graffiti) who are breaking larger and larger chunks of “reality” into their work. (Reality, as Nabokov never got tired of reminding us, is the one work that is meaningless without quotation marks.)

What did the critics say? Some appreciated it, others not so much.

In the New York Times Book Review, Luc Sante was open to Shield’s vision:

On the whole . . . he is a benevolent and broad-minded revolutionary, urging a hundred flowers to bloom, toppling only the outmoded and corrupt institutions. His book may not presage sweeping changes in the immediate future, but it probably heralds what will be the dominant modes in years and decades to come. The essay will come into its own and cease being viewed as the stepchild of literature. Some version of the novel will endure as long as gossip and daydreaming do, but maybe it will become more aerated and less controlling. There will be a lot more creative use of uncertainty, of cognitive dissonance, of messiness and self-consciousness and high-spirited looting. And reality will be ever more necessary and harder to come by.

In The Guardian, Blake Morrison wrote:

Shields sells fiction short. “Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole,” he claims. Does it? Isn’t this patronising to novelist and reader alike? Can’t wresting order out of chaos be a triumph against the odds? And what exactly is this hated creature, the “conventional” or “standard” novel? The premise is that because life is fragmentary, art must be. But poems that rhyme needn’t be a copout. And novels with a clear plot and definite resolution can still be full of ambiguity, darkness and doubt. By the same token, to engage with the dilemmas of an imaginary character means learning to empathise with otherness, and few skills are more important in the world today.

Shields has written a provocative and entertaining manifesto. But in his hunger for reality, he forgets that fiction also offers the sustenance of truth.

In The New Yorker, James Wood was mostly unimpressed.

Shields prosecutes an effective, if coarse, sub-Barthesian argument against the traditional novelistic machinery. He rants a bit, apparently fearful that if he were quieter we would not believe in his sincerity; hungry for his own reality, certainly, he also mentions himself a great deal . . . Like most aesthetic manifestos, his book is an argument for realism; it’s just that he prefers his kind of realism to that of traditional fiction, which strikes him as fake.

. . .

His complaints about the tediousness and terminality of current fictional convention are well-taken: it is always a good time to shred formulas. But the other half of his manifesto, his unexamined promotion of what he insists on calling “reality” over fiction, is highly problematic. A moment’s reflection might prompt the thought, for example, that Tolstoy (who so often reproduced reality directly from life) is the great “reality-artist,” and a powerful argument against Shields’s anti-novelistic religious fury. When one first reads Tolstoy, one feels the bindings being loosed, and the joyful realization is that the novel is stronger without the usual nineteenth-century appurtenances—coincidence, eavesdropping, melodramatic reversals, kindly benefactors, cruel wills, and so on. It is hard to imagine a writer more obviously “about what he’s about.” Strangely enough, using Shields’s aesthetic terms and most of his preferred writers (along with some of those he seems not to prefer), a passionate defense of fiction and fiction-making could easily be made. Perhaps he will write that book next.

And then there’s Sam Anderson:

And seven years later, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Stephen Marche argued that the novel was only published before its time:

“The lifespan of a fact is shrinking,” Shields wrote in 2010. “I don’t think there’s time to save it.” Time for the fact officially ran out on November 9, 2016, leaving us faced with numbing and confounding questions that Reality Hunger posed early and urgently: How do we find the truth in an age when technology and politics have rendered the line between fiction and nonfiction nearly impossible to distinguish? How do we write about the real world when reality itself is up for grabs? Reality Hunger has become, quite unintentionally to its author, a book about how to write now, in 2017.

That’s still up for debate.

Previous Article

The Booksellers’ Year in Reading:Part Two