100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

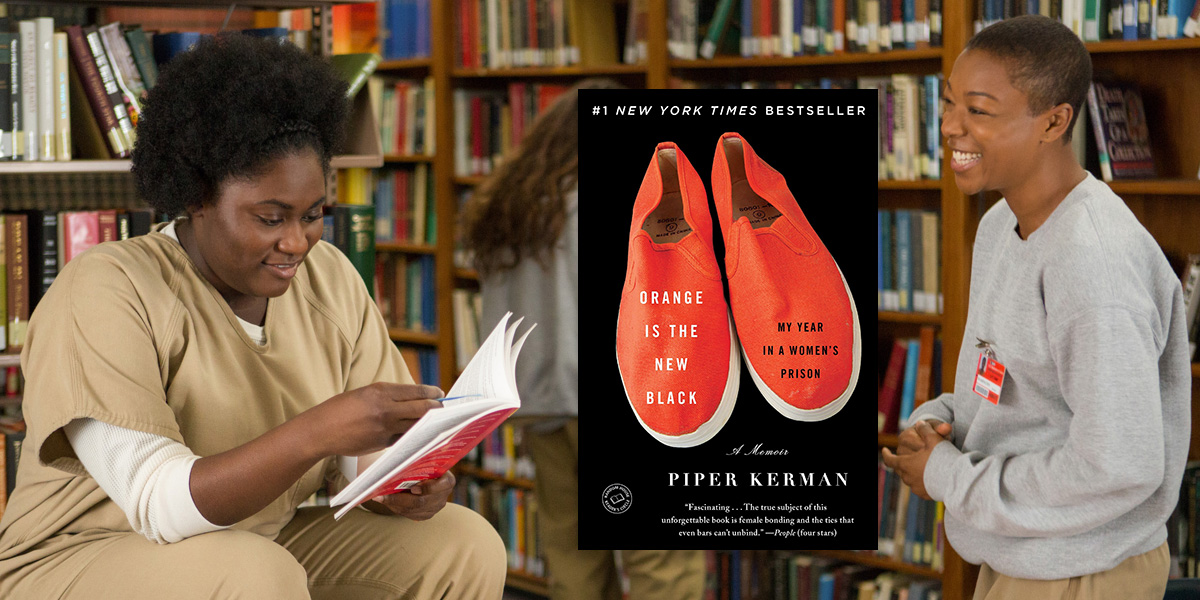

Piper Kerman, Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison (2010)

Two hundred women, no phones, no washing machines, no hair dryers—it was like Lord of the Flies on estrogen.

*

Essential stats: The most important stat about “nice blond lady” Kerman’s extremely buzzy memoir of her time in a women’s federal prison is, of course, that it was adapted into the long running television show (2013-2019) of the same name, which in the New York Time’s look back at the decade in culture, Wesley Morris called “the best show on TV, in any format.” It was Netflix’s most watched original series this decade. In fact, many reviewers concluded that the show was much better than its source material—but then again, the show had a lot more time.

What did the critics say? Opinions were mixed. In Slate, Jessica Grose wrote:

If you pick up Kerman’s book looking for a realistic peek inside an American prison, you will be disappointed. Orange Is the New Black belongs in a different category, the middle-class-transgression genre. . . . The tales of these well-educated women follow essentially the same narrative arc: Girl is bored, girl seeks titillating transgression, girl regrets, girl renounces prior misdeeds, girl lives happily ever after. The girl never serves out a life sentence carving deadly points on toothbrushes or ends up a strung-out old lady on a street corner.

J. Courtney Sullivan was somewhat gentler in the Chicago Tribune, calling it “a perceptive, if imperfect inside look at our criminal justice system and the women who cycle through it.”

Ok, so the real import of the book is the show. What made that so good? As TIME’s TV critic Judy Berman wrote, Orange Is the New Black is the most important television show of the decade because not only was it good, but it smashed all the molds around it:

When it came to representation, this wasn’t merely the first prestige show since The Wire built around poor and nonwhite people—or the rare program intended for a general audience that featured more than a token queer regular. It also endowed each of these characters with stereotype-defying specificity. In 2014, when this magazine declared that America had reached a “transgender tipping point,” Laverne Cox’s breakthrough role as trans inmate Sophia Burset made her the face of that moment. For once, women whom mainstream society habitually ignored were being represented in pop culture as individuals with virtues and flaws, rather than as a monolithic mass of degenerates or vixens.

The show’s mix of gallows humor and high tragedy disrupted genre categories to the extent that the Emmys moved it from comedy to drama between Seasons 1 and 2. And over the years, its unflinching depiction of the American justice system has both mirrored and catalyzed intensifying debates around mass incarceration, private prisons, systemic racism, economic inequality and police violence against people of color. Some of these story lines have been controversial: Kohan got blowback for having a guard kill Samira Wiley’s bighearted Poussey Washington at the end of Season 4. Maybe the point was that even Litchfield’s gentlest inmate could be a casualty of police brutality, but many fans just saw another black body sacrificed in service of a plot twist. Still, the conversations that have come out of Orange’s perceived missteps have felt as vital as the ones around its successes.

Previous Article

The Booksellers’ Year in Reading:Part Two