100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

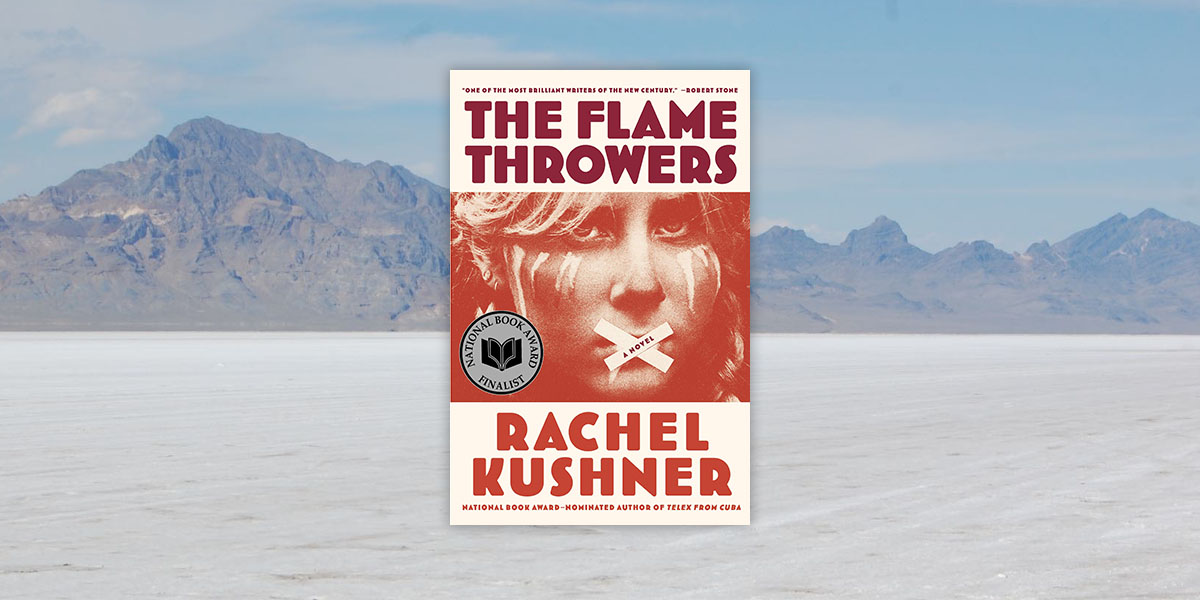

Rachel Kushner, The Flamethrowers (2013)

The desire for love is universal but that has never meant it’s worthy of respect. It’s not admirable to want love, it just is.

*

Essential stats: It was a bestseller and a National Book Award finalist; it was New York magazine’s favorite book of the year, and it was on pretty much everyone else’s list—because, and this of course is the most important stat of all, everyone you knew in 2013 was reading it.

What did the critics say? There was some arguing. James Wood loved it, and so did Ron Charles, and Maud Newton, and Christian Lorentzen, and Tom Bissell—a veritable who’s who of book reviewers. But in The New York Review of Books, Frederick Seidel was less enthused, complaining that the book was “somehow lacking in feeling.” Heat but no warmth, as he put it. Shortly thereafter, Nicholas Miriello rebutted Seidel’s review (imagine!) in The Los Angeles Review of Books, calling it “gallingly condescending” and “often inadequate” and noting that “Seidel at times doesn’t even bother writing complete sentences, let alone a sound argument.” Zing. He concludes:

Ultimately, the problem with this review is that Seidel seems to think he, not the book, is the star of the essay, and so we are treated to endless personal asides—his motorcycles, his gasps, his pondering of why he was chosen to review this book—and unsupported opinion that blends into repurposed summary that blends into more unsupported but cruel opinion once more. The review doesn’t come out and say it, not explicitly anyway, but its form, its mere existence says enough: The book doesn’t deserve a proper review, Seidel is implying, so I haven’t given it one.

Suffice it to say, the book was polarizing, and its fans passionate. But wait, just one more, which is close to my heart: at Tablet, Adam Kirsch wrote:

What makes The Flamethrowers a book for our moment is the way it implodes all the usual assumptions about what gender means in literature. Are “women’s novels” supposed to have robin’s-egg-blue covers and deal with domestic issues and personal relationships and offer likable protagonists?

. . .

Kushner is out to create a mystique, and her book is full of portentous atmosphere and self-conscious cool. In other words, The Flamethrowers manages to be a macho novel by and about women, which may explain why it has been received so enthusiastically by the critics.

. . .

The novel itself is, if not “mansplaining,” at least always insisting on its own mystique. But a novelist should not be a mythmaker, not when one of the greatest powers of the novel is the ability to penetrate the myths we make about ourselves—to show how things really work, instead of how they claim to work. The Flamethrowers is too cool, too stylish; in this it resembles some of the most famous writing of the 1970s, including Robert Stone’s novels and Joan Didion’s essays.

This, you may not be shocked to learn, irritated yours truly—and it irritated Kushner too, though she was nicer about it than I was.

About the cover: Interesting story. As Kushner wrote in The Paris Review:

The first image I pinned up to spark inspiration for what would eventually be my novel The Flamethrowers was of a woman with tape over her mouth. She floated above my desk with a grave, almost murderous look, war paint on her cheeks, blonde braids framing her face, the braids a frolicsome countertone to her intensity. The paint on her cheeks, not frolicsome. The streaks of it, dripping down, were cold, white shards, as if her face were faceted in icicles. I didn’t think much about the tape over her mouth (which is actually Band-Aids over the photograph, and not over her lips themselves). This image ended up on the jacket of The Flamethrowers, whose first-person narrator, introduced in this issue, in the story “Blanks,” is a young blonde woman. A creature of language, silenced.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.