100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

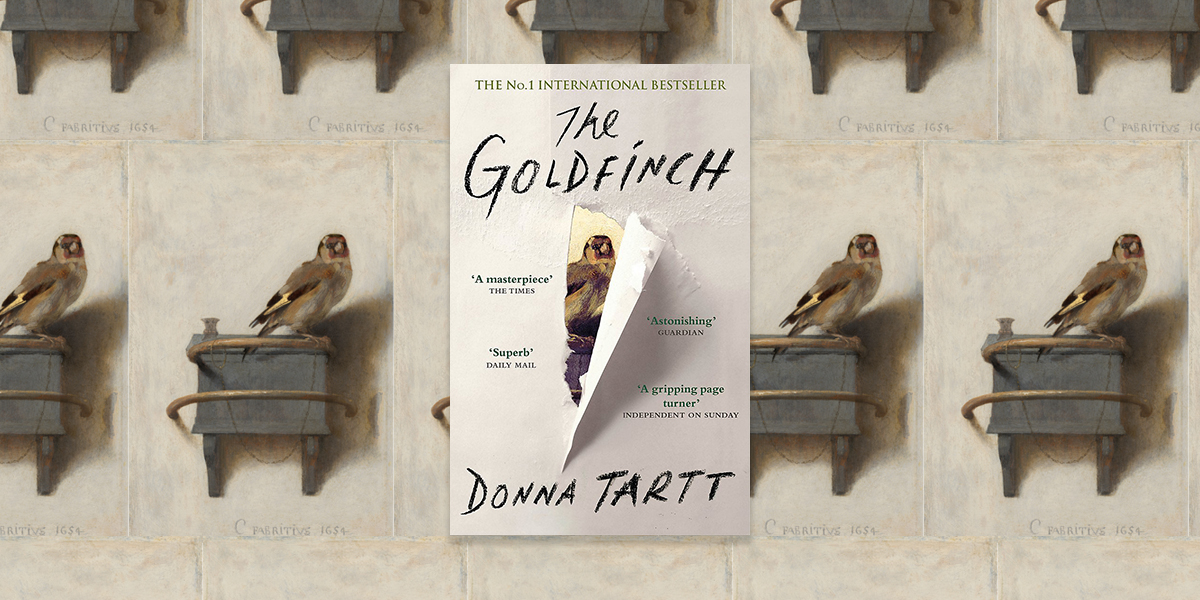

Donna Tartt, The Goldfinch (2013)

Caring too much for objects can destroy you. Only—if you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it? And isn’t the whole point of things—beautiful things—that they connect you to some larger beauty?

*

Essential stats: Tartt’s longest, most Dickensian novel was, of course, an international #1 bestseller, and spent more than 30 weeks on the New York Times list, selling some million and a half copies in the first year. It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction in 2014, and was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Baileys Women’s Prize.

Why was it defining? Well, the revered lady Tartt only blesses us with a novel once a decade, so every time she does it’s a major event. But this novel was more than that: it was without question the most anticipated and discussed novel of the year—so big that even the Frick, a stuffy (if lovely) museum in New York City that happened to have the painting in question on hand, became a major tourist destination.

But it also sharply divided critics. As Evgenia Peretz put it in Vanity Fair, in addition to the mountains of praise (and, you know, that Pulitzer) the book also received “some of the severest pans in memory from the country’s most important critics and sparked a full-on debate in which the naysayers believe that nothing less is at stake than the future of reading itself.”

Wait, what happened to the future of reading? Spoiler alert: it’s still there.

Okay, whew, go on: Michiko Kakutani loved it, citing “the Russian masters” and calling it “enthralling.” James Wood sniffed in The New Yorker that it was “a virtual baby: it clutches and releases the most fantastical toys,” but also that it was for babies: “Its tone, language, and story belong to children’s literature.” After Tartt was awarded the Pulitzer, Wood told Vanity Fair: “I think that the rapture with which this novel has been received is further proof of the infantilization of our literary culture: a world in which adults go around reading Harry Potter.” Yikes.

As Peretz wrote, “No novel gets uniformly enthusiastic reviews, but the polarized responses to The Goldfinch lead to the long-debated questions: What makes a work literature, and who gets to decide?” That is, is it about the story, or the way the story is told? Is it about what the critics think, or what the readers think? The answer, of course, is that it is about all of these, and none, and everyone should just decide for themselves what they like and leave it at that.

To cap things off, there’s the terrible film adaptation:

But hey, seriously, friend to friend, is the book any good? As a reasonably well-read senior editor at a literary website and the most devoted fan of The Secret History there ever was, I say: I mean, it could have used some more editing. But boy was it fun.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.