100 Books That Defined the Decade

For good, for bad, for ugly.

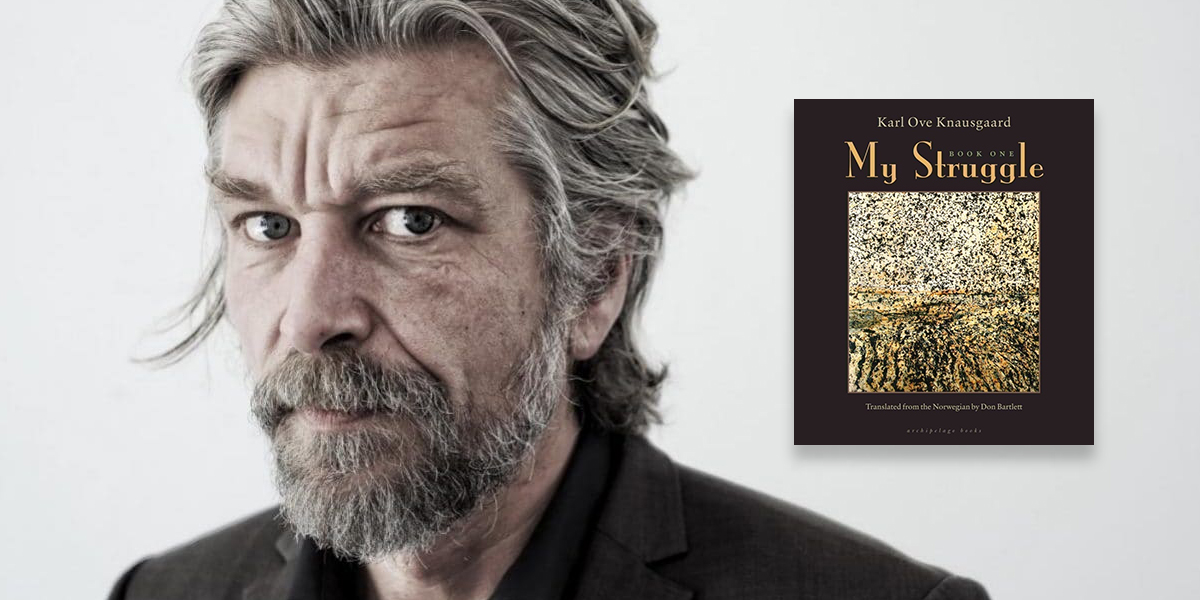

Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Don Bartlett, My Struggle: Book 1 (2012)

As your perspective of the world increases not only is the pain it inflicts on you less but also its meaning. Understanding the world requires you to take a certain distance from it. Things that are too small to see with the naked eye, such as molecules and atoms, we magnify. Things that are too large, such as cloud formations, river deltas, constellations, we reduce. At length we bring it within the scope of our senses and we stabilize it with fixer. When it has been fixed we call it knowledge.

*

Essential stats: the first of six books, which would total some 3,600 pages, and which were massive bestsellers in his native Norway, put up modest sales in the US and UK but had outsize impact on the literary landscape.

Why was it defining? A Knausgaard stand-in appeared on Younger feeding candy to Hannah Montana in Sockerbit, which is how, if you’re any sort of publishing-adjacent person, you really know you’ve made it:

Why was it really defining? There are only a few modes of literature that could be said to have definitively defined the decade, and one of them is “autofiction,” of which Knausgaard is the Platonic ideal—or as John Williams put it, “the sun in this genre’s planetary system.” Tying the My Struggle series to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels (see below), Charles Finch recently wrote:

In overlapping moments, these two Europeans’ respective multivolume novels won huge rapid fame — for being highly personal, very long and perhaps more than anything for the unusual, almost guilty intensity with which people devoured them. (As The Times’s Dwight Garner memorably commented, reading the first volumes of Knausgaard’s My Struggle was like “falling into a malarial fever.”) Above all, they were close to identical in their most serious and unexpected offer to the reader: unmediated access, over many pages, to precisely one other consciousness.

. . .

Knausgaard and Ferrante promise so little. But they give it. Each recounts, in the close first person, the inside of a human life. That’s something innumerable writers have done, obviously, but they seemed to do it in a newly dangerous way — with a pitiless, dispassionate modesty of ambition. Neither narrator extrapolates larger truths from experience. Both trust themselves as far as their own fingertips; Ferrante portrays the intricate social world of working-class Naples, but in a state of constantly renewed bafflement, while Knausgaard (“He broke the sound barrier of the autobiographical novel,” the novelist Jeffrey Eugenides told a reporter for The New Republic) abandons almost all narrative pretense to describe his time on earth as straightforwardly as he can.

The effect this method had on me, and I believe on many people, was one of immediate trust and identification. Somewhere in the stretch between Sept. 11, 2001, and the 2016 election, such limited claims to certainty came to seem not unambitious, but like the only sane rejoinder to the world as it had become. And the length of the books — their uncompressed, occasionally boring plots — created a profound new version of the self-forgetting that the best stories give us.

But are the books amazing or boring? Both, I guess. General consensus in the literary office is that the first book is good, and that the rest of the series descends into annoying navel gazing. This writer’s belief is that the first paragraph of the first book is good, and the rest of the series descends into annoying navel gazing. Don’t @ me with your pearl clutching, Karl Ove stans.

Extra credit: Knausgaard on John Fosse · Knausgaard on ice cream · Knausgaard on writing

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.