At this point, what is really left to say about 2020? It was pretty bad, overall. Some parts were okay. There were some good books. There were some bad actions. There were some much-needed reckonings. Our lives and listicle intros were overwhelmed by a deadly pandemic (bad), a treasonous president (worse), and righteous protests (better, but bittersweet). Still, time stops for no man nor website, and soon it will be 2021. Is the transition from one year to the other symbolic at best? Of course. But this is how we register the shape of our lives, not to mention our content, so there’s no use stopping now.

Below, you’ll find the second installment of our countdown of the 50 biggest literary stories of the year, so you can remember the good (yes, there was some!), the bad, and the Zoom book launch. Join us, won’t you, on this very special journey.

30. Barnes & Noble tried its hand at diversity. . . and failed miserably.

In February (remember February?), Barnes & Noble and Penguin Random House came together to bring the world “Diverse Editions.” This special series was “part of a new initiative to champion diversity in literature.”

That sounds like a good idea, right? Want to know how they were going to encourage this diversity in literature? By slapping characters of color onto the covers of classics by white writers. Yes, the twelve titles getting this cool, woke treatment were: Alice in Wonderland, Romeo and Juliet, Three Musketeers, Moby Dick, The Secret Garden, The Count of Monte Cristo, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Emma, The Wizard of Oz, Peter Pan, Treasure Island, and Frankenstein. Just in time for Black History Month!

The initiative was immediately met with criticism calling out their superficial attempts at diversity and inclusion. They rolled it back, saying in an official statement: “The covers are not a substitute for Black writers or writers of color, whose work and voices deserve to be heard.” In summation: simply read more books by Black writers. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

29. #PublishingPaidMe revealed disparities between payment of white writers and writers of color.

As we reported at the time, in early June, a hashtag took Book Twitter by storm. #PublishingPaidMe, kicked off by author LL McKinney, was a refreshing act of financial transparency in which writers shared their advances. (Among the most shocking and rage-inducing was the fact that Jesmyn Ward only received $100K for Sing, Unburied, Sing despite Salvage the Bones’ major National Book Award win! For reference, this white man received an $800K advance for his debut.)

As Jonny Diamond wrote, “#PublishingPaidMe [was] in some ways a response to the now ubiquitous corporate declarations of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement (some of these are substantive, most are not), and is—as an exercise in financial transparency—an important way of putting a number on the systemic racism that undergirds American society, including publishing.”

So to the companies that are making sweeping statements of solidarity as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, I hope it isn’t purely performative. Put your activism where your advances are! –KY

28. Nikil Saval got into politics!

After defeating incumbent Larry Farnese in the Democratic primary race for Pennsylvania’s 1st District senate seat, Nikil Saval—former editor of literary and political magazine n+1, where he still serves on the Board of Directors—went on to win the seat officially on election day (one of the few definitely, inarguably good things that came out of that semi-cursed night). Endorsed by Bernie Sanders, Saval will now represent large parts of South Philly as a Democratic Socialist. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

27. Skyhorse publishes everyone else’s canceled books.

The Trump era will be defined by many things: greed, racism, incompetence, irreality… But the last four years has also been a boom time for opportunistic grift, from the president on down. Enter Skyhorse, the “renegade” publishing house who will go where others dare not. In 2020 alone, Skyhorse published Woody Allen’s memoir (canceled by Hachette after internal protest), a Garrison Keillor novel, and an Alan Dershowitz defense of Donald Trump; and while one might take issue with the alleged personal transgressions of these men there really isn’t an argument to be made against anyone’s right to publish them. Where things get trickier, though, is when lives are at stake: Skyhorse also publishes anti-vaxx, anti-mask propaganda, justifying the dissemination of misinformation with a now familiar “free speech” argument about both sides of a given subject, even when that subject is based in fact, not opinion. “More speech defeats bad speech” used to work when we all lived in the same public square but these days, when we turn life-saving matters of scientific fact into a “debate,” people die. Oh, and per this delicately titled Vanity Fair exposé, “Skyhorse Publishing’s House of Horror,” it’s also not a great place to work. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Photo: Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times

Photo: Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times

26. Viet Thanh Nguyen became the first Asian American on the Pulitzer Prize Board.

In September Viet Thanh Nguyen, joined the Pulitzer Prize Board as its first Asian American and Vietnamese American member. As we noted in The Hub, “The Pulitzer co-chairs—Stephen Engelberg of ProPublica and Aminda Marqués Gonzalez of the Miami Herald—said in a statement they were ‘delighted’ at his addition to the board: ‘His remarkable range of experiences as a novelist, journalist, essayist and scholar make him a wonderful addition to the board in this time of extraordinary ferment.'” Nguyen, a professor at the University of Southern California, won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Sympathizer and packs a punch on Twitter. (Fans, we’re getting the sequel to The Sympathizer in March 2021!) –EF

25. The rise of funding and aid networks for writers and booksellers.

For many reasons we need not go into here, 2020 has been a terrible, hard year for millions upon millions of people. But if we must find a silver-lining, it is that in the absence of basic government intervention, Americans of all walks of life took it upon themselves to organize support networks of mutual aid; and while many had been doing this work all along, for others it was something of an awakening to the power of very local politics.

The literary and bookselling communities (particularly the latter) have always consisted of supportive networks, and as the pandemic started to take its toll on lives and livelihoods, the book world snapped into action: always at the forefront of bookseller support was The Book Industry Charitable Foundation (BINC) which reported at the end of May that requests for assistance had increased by 321 percent; The Bookstore at the End of the World, a collective of unemployed and underemployed booksellers, organized a digital storefront at Bookshop.org and declared themselves “unemployed and open for business!”; ArtistRelief.org raised $10 million for artists and writers; the National Book Foundation, the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses, and the Academy of American Poets created the Literary Arts Emergency Fund for literary nonprofits and small publishers; PEN America launched an Emergency Writers’ Fund. All of this organizing (and there was a lot more!) also saw an increased awareness of publishing workers’ rights, so the formation of a group called Book Worker Power—which aims at “building worker power in the world of books”—came as no surprise. One can only hope these very hard won lessons of precarity stay with us in happier times. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

24. The romance industry faced a good ol’ reckonin’.

Just in time for Valentine’s Day, the board of the Romance Writers of America resigned.

As previously reported at Lit Hub, the leadership shake-up came after a debate over Kathryn Lynn Davis’s 1999 novel Somewhere Lies the Moon; writer Courtney Milan called the book’s descriptions of Chinese women racist, and Davis along with writer Suzan Tisdale filed complaints against her with the organization. The RWA disciplined Milan, which was the final straw for a number of members that said it was just the latest example of the organization failing to address racism within the community. In May, the organization replaced its annual RITA Awards, which has never awarded a Black author, with the Vivian, announcing it would rework the selection ad judging process and add “a category devoted to recognizing unpublished authors.”

N. K. Jemisin said on Twitter that the mess should be instructive for other literary organizations and publishers that need to address similar issues, adding, “Whew, 2020 has been a year already, huh?” She wrote that in early February. February! I’ll leave you with that. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

23. The last volume of Hilary Mantel’s beloved Cromwell trilogy was published, but alas, it did not net her a Booker three-peat.

In March, Hilary Mantel published The Mirror & The Light, the final installment in the wildly popular and critically acclaimed trilogy that began with Wolf Hall, and which already has two (2) Booker prizes to its name. In July, as anyone might have expected, the Booker Prize announced its 2020 longlist, and there it was, along with eight debuts, ready for the three-peat. Alas, it was not to be. The Mirror & The Light did not make the shortlist. Gasp! But why? Judge and novelist Lee Child told The Guardian that The Mirror and the Light was “an absolutely wonderful novel, there’s no question about it,” but “as good as it was, there were some books which were better.” Fair enough. What did Dame Hilary Mary Mantel have to say? While she told the Sydney Morning Herald she was disappointed, she also explained to the Guardian that she “respect[s] the judges’ decision because I’ve been a judge and it’s very hard. I accept that books are born in a certain cultural moment. They surf on the tide of the times. In some ways I feel freed, too. I think the trilogy is built to last,” she said. “There’s nothing I can say except to congratulate everyone on the shortlist.” –ET

22. We saw the rise and fall of the National Emergency Library project.

Back in March, in the early days of the pandemic, the Internet Archive (whatever that is) drew the ire of publishers and authors around the country by releasing some 1.4 million digitized books to the public for free in response to the shuttering of bookstores and libraries caused by the coronavirus pandemic, suspending their normal 14-day lending schedule.

“This suspension will run through June 30, 2020, or the end of the US national emergency, whichever is later,” read the announcement for the launch of the National Emergency Library (italics mine because, you know, lol).

On first hearing, a mysterious digital library throwing open its doors to the shut-in masses sounded wonderful, but the NEL pissed a lot of people off.

First came the Author’s Guild:

The Authors Guild is appalled by the Internet Archive’s (IA) announcement that it is now making millions of in-copyright books freely available online without restriction on its Open Library site under the guise of a National Emergency Library. IA has no rights whatsoever to these books, much less to give them away indiscriminately without consent of the publisher or author. We are shocked that the Internet Archive would use the Covid-19 epidemic as an excuse to push copyright law further out to the edges, and in doing so, harm authors, many of whom are already struggling.

Then, on June 1, a group of book publishers—Hachette, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House, all member companies of the Association of American Publishers—filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against the Internet Archive.

In the end, the National Emergency Library was forced to shutter its digital doors. Goodnight, sweet, copyright-infringing prince. –DS

21. The Associated Press (AP) revised its style guide, and will now capitalize the “b” in “Black.”

Following the national uprisings and global protests in response to the murder of George Floyd and longstanding police violence, the Associated Press and many news organizations released statements declaring that they would begin to capitalize the letter “b” in the word “Black” when referring to Black people and communities.

“Black with a capital B refers to people of the African diaspora. Lowercase black is simply a color,” wrote Lori Tharps, a journalism professor at Temple University. “We are a community of people who deserve to be reference with the capital letter. We are not speaking of people’s skin color, we are speaking of a culture.”

While the Seattle Times and Boston Globe made this stylistic change last year (and while other Black news outlets like Essence and the Chicago Defender advocated for and made this change for years), this mass revision follows calls for journalists to confront their own racial biases, coverage choices, and hiring practices. We mustn’t forget that some of the same organizations that made this change were also the ones to publish anti-Black pieces on police violence.

“When people are offended by how we describe their community, we have to listen,” said Cristina Silva, an editor at USA Today and co-chair of the newspaper’s diversity committee, in a statement. –Rasheeda Saka, Editorial Fellow

20. Famous people read a lot of literature to us through our screens.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought forth the near extinction of celebrity culture (or, at least, I prefer to think it almost did). As America was thrown into crisis in early March, celebrities not only fled to their second (or third or fourth…) homes but also took to social media to offer words of consolation and gestures of solidarity that struck a hollow chord with many folks, especially those who were and are bearing the brunt of our current pandemic.

Like the literary world (and pretty much all the worlds), the world of entertainment and celebrity had important questions to ask of themselves—like, what do we do now, given that our entire careers are largely based on the amount of attention we receive? Or perhaps (for the less cynical), what should we do now to stay informed and use our platforms for good, instead of spewing out ready-made platitudes of feel-good optimism and “positive vibes only” affirmations?

For some, this meant creating book clubs or joining online reading initiatives. Ethan Hawke, for one, recently recorded a three-hour abridged version of Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. (And he even shared some of his insights and general love of Robinson’s work.)

Earlier in March, a coterie of actors (hello Tilda Swinton, Iggy Pop, Marianne Faithfull, and Jeremy Irons) teamed up with the Art Institute of Plymouth University to offer a grand reading of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which they hoped would speak to such an intensely isolating and lonesome period.

Actor Patrick Stewart offered a daily recitation of a Shakespearean sonnet for a few months. And Jimmy Fallon, Betty White, and Jennifer Garner took to reading children’s books with the hopes of giving overloaded parents a generous respite.

Even elite fashion model Kaia Gerber launched an Instagram book club this past spring, where she read such titles as Sally Rooney’s Normal People, Laurie Frankel’s This Is How It Always Is, and Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. I was able to attend one such meeting and watched as Gerber brought Jia Tolentino on her Instagram (IG) Live for a discussion of Trick Mirror and the way social media acutely impacts the lives of teenagers.

If there’s anything this pandemic has taught us, among its many lessons, it is that literature will always be there for us in times of crisis and joy. And that it might even be enough to rescue and polish the tainted image of celebrity. –RS

19. Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize.

After choosing, in 2019, to bestow the highest honor in the literary world upon a man who defended the genocidal regime of Slobodan Miloševic, the Swedish Academy regained some credibility in October when it awarded American poet Louise Glück the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Despite being a Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winner, as well as a former US Poet Laureate and National Humanities Medal recipient, Glück hadn’t been considered among the favorites to pick up this year’s prize. Her win makes Glück the first American woman to receive the prize since Toni Morrison in 1993.

The prize committee cited Glück’s “unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal,” with the committee Chair Anders Olsson noting, “In her poems, the self listens for what is left of its dreams and delusions, and nobody can be harder than she in confronting the illusions of the self.”

When asked where newcomers to her work should start, Gluck replied, “I would suggest they don’t read my first book unless they want to feel contempt. But everything after that might be of interest. I like my recent work. Averno would be a place to start, or my last book Faithful and Virtuous Night.”

Here is Glück on realism and fantasy, as well as her thoughts on how she writes. –DS

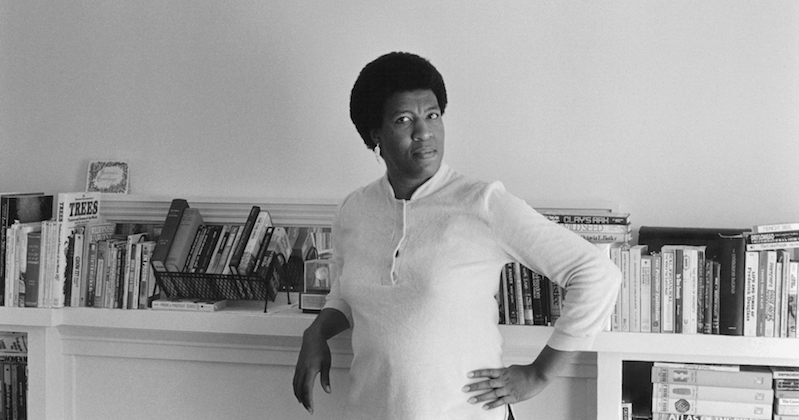

18. The New York Times bestseller list caught up with Octavia Butler.

Fifty years after selling her first story, and fourteen years after her untimely death, the revered science-fiction author Octavia Butler landed on the New York Times’s bestseller list—one of Butler’s dreams—with one of her most popular novels, Parable of the Sower.

The news was warmly greeted and not too surprising. Butler inspired a generation of speculative fiction authors and prominent Afrofuturist cultural figures, from Nnedi Okorafor to Janelle Monáe.

In the years since Donald Trump’s 2016 election, Butler’s work has experienced a resurgence—from illustrated adaptations of her novel Kindred to the creation of a fellowship in her name and an array of essays and commentaries on her work.

The Butler revival is in some ways comparable to the renaissance James Baldwin’s work has seen in roughly the same period, thanks in part to the award-winning 2017 documentary I Am Not Your Negro. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

17. We were introduced to The Chain.

Last year all the literary young wans went mental over Sally Rooney’s perfect “millennial novel” Normal People, and for good reason. This year, the literally captive audience we all became were gifted with Rooney’s adaptation of the novel for television, a twelve episode EVENT that sparked a million reviews and roundtables, think-pieces, behind the scenes descriptions (and also, critically, introduced American audiences to Liveline). Lorrie Moore liked it! (If you don’t want to read her whole review, here are our favorite ten sentences) Lit Hub ran a piece about what it was like being an extra on the show. But the true star of Normal People was Paul Mescal/Connell’s chain, an Argos catalogue-cheap loop of silver links laid across the hairless, agricultural chest of history’s most smoking minor hurler. And, look, I know I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know. Googling “Connell’s chain” produces 40K website results, and you’ve read most of them. From “There’s *Much* More To Connell’s Chain Than You Realise” to “Snag a Chain Like Connell’s from Normal People for Less Than $50.” Also: “Connell’s Normal People Chain Has Its Own Instagram Account And It’s Time We Talk About It” and “Is This the Sexiest Thing About Normal People?” The chain, that is to say, is, like, more than a chain? It’s a symbol; it’s a phenomenon. In Bakhtinian terms, it is a chronotope, a site of literary space-time, super-dense with meaning. The chain is wherein all that is desire and longing in 2020 has been cathected and set to simmer. And trust me, I get it—when I was 23 I dated an Irish guy who wore an Argos chain. And Reader, I married him. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

16. President Barack Obama published his memoir and saved Christmas.

As I “reported” earlier this year, not even the Booker Prize can compete with the awesome power of the Obama Publishing Machine. The Booker Prize Foundation announced back in September that it was moving the virtual announcement of its 2020 winner from November 17 to November 19 to avoid a conflict with the release of Barack Obama’s memoir, A Promised Land.

Was this a humbling admission by the Booker folks of their place in the global literary pecking order? Yes. Was it also a wise decision, given the expected magnitude of the post-election Obama memoir rollout. Also yes.

To meet what is expected to be unprecedented demand, A Promised Land (the 768-page first of two volumes by the Reader in Chief) is getting an Ent-enraging three million copy first printing and will surely dominate the literary landscape well into the new year.

Back in early 2018, Barack and Michelle Obama sold their memoirs to Crown as a package deal for a record-breaking $65 million. Michelle did her bit to pay off the advance, selling more than 8.1 million units of Becoming in the United States and Canada. Now it’s Barack’s turn, and the smart money is on A Promised Land shifting north of two million copies before his former VP takes office on January 21.

Who knows, if everyone remembers to shop indie instead of Amazon this holiday season, Obama’s memoir may just help some beleaguered independent booksellers reach their own promised land (post-COVID solvency). –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

15. A novel about sexual assault was the subject of controversy, but not for the reasons you might think.

Kate Elizabeth Russell’s hotly anticipated debut novel, My Dark Vanessa, about a woman who was preyed upon by her high school English teacher and remains convinced that their skewed relationship was born out of love, was released to much fanfare in March of this year—yet accusations of privilege, unearned advances, and industry racism had emerged long before publication date. At the end of January, Latina author Wendy Ortiz published an article that detailed the similarities between My Dark Vanessa and her own 2014 memoir of an abusive relationship with a teacher, as well as criticizing industry gatekeepers for pouring resources into the work of white women while undercutting the potential success of authors of color. Coming soon after the controversy over American Dirt, the article created a new firestorm of debate, especially given that My Dark Vanessa had received a similarly sizable advance and large amount of publisher support.

Kate Elizabeth Russell took down her Twitter profile and retreated from the limelight, before making a statement about her own experiences of sexual abuse, allaying any further accusations of plagiarism. Despite Russell’s statement, Oprah’s Book Club, reeling from their experiences with American Dirt, dropped My Dark Vanessa as their March selection. While publishing pay disparities and gatekeeping are acknowledged and long-standing issues, publishers are often willing to pay much higher advances for commercial fiction than thoughtful memoirs, adding further complexity to the issue. The general consensus, when the dust cleared, was that the issues Wendy Ortiz raised are real, but not the fault of Russell. The book went on to become a huge bestseller. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

14. Resignations, open letters, and lawsuits swirled around the National Book Critics Circle.

As this summer brought a widespread uprising over racism in the US, it also revealed the fault lines in literary organizations that have failed to adequately address racism in their own house. One place where that conversation blew up: the National Book Critics Circle.

In early June, a committee of NBCC board members drafted a statement affirming the NBCC’s support for writers of color, then circulated it among the rest of the board for review. Carlin Romano, a board member who has courted controversy in the past—including in 1994, when he publicly speculated about raping a legal scholar in a book review, just to prove a point about her work—responded in an email that was critical of the statement and of the premise that white people in positions of power have inadequately supported marginalized writers. “I resent the idea that whites in the book publishing and literary world are an oppositional force that needs to be assigned to re-education camps,” he wrote.

The fallout was fast. Board member Hope Wabuke posted the email thread on Twitter; a number of board members resigned; the remainder began discussing how to remove Romano from his position, and in response, Romano threatened to sue the board along with individual board members. Finally, the membership organized a vote in late August, in which Romano, narrowly, prevailed. He’ll keep his seat through the end of his term in 2022.

David Varno, who was elected NBCC president following the flurry of resignations, attributed Romano’s win in part to the fact that he had instilled the fear of litigation in fellow members. “Before the meeting, Carlin threatened people with litigation and made people feel afraid to vote for removal and afraid to state why he should be removed,” he told Publishers Weekly.

Sounds like a great way to hang onto power! –CS

13. The heads of the Poetry Foundation resigned.

In June, when the country was rocked by protests over the killing of George Floyd, the Poetry Foundation—which has drawn criticism before for exclusionary practices that seem to favor white people—published a statement that was only slightly more lengthy than a bumper sticker and seemed about as well-considered. A group of prominent poets, including Kaveh Akbar, Ocean Vuong, and others responded with an open letter calling its statement “worse than the bare minimum”; they also said they would stop contributing to Poetry or collaborating with the foundation until it made a more substantial commitment to anti-racism and to supporting marginalized poets.

The dispute led to the resignation of president Henry Bienen and Willard Bunn III, chair of the Board of Directors, in June. Two months later, Poetry editor Don Share also resigned following backlash over a poem in the July/August issue that uncritically used racist language. After that, the organization announced it would, for the first time in more than 100 years, pause publication on Poetry for a month while it addressed the editorial process and hiring practices there. While that process seems to be ongoing, the organization’s critics say it has a long way to go. –CS

12. A new genre was born. Let’s call it COVID-lit.

The pandemic brought us a slew of quarantine diaries and Goodbye to All That essays with a shiny new angle. Meghan Daum wrote about fleeing NYC for the Appalachian mountains, Mira Jacob depicted her family’s escape in graphic form, Bryan Mealer left New York just like his ancestors, and even Masha Gessen went to Cape Cod.

Predictably, there was backlash. Quite a bit of it. “As essays go, these are limp specimens, outbursts of defensiveness gussied up with sentimental riffs about meadows and streams, the ghosts of pandemics past, and a washer-dryer in the home,” wrote Claire Fallon in HuffPost. “The revelations they hold are both deeply boring and deeply annoying.” The essays acknowledged race and class privilege, or they did not, and many shrugged at yet another iteration of white flight. (Also, Twitter wanted to know, weren’t New Yorkers . . . supposed to be staying put?)

Much less offensive (to most) were the fictions that cropped up, likely requested by editors looking for something both topical and safe. Call it the rebirth of an ancient genre—the New York Times did.

And that doesn’t even include all the crashed-out Covid books, of which there have already been so many that they necessitate a list. More are coming. So many more. –ET

11. Svetlana Alexievich took a stand during the political crisis in Belarus.

One of the year’s most volatile, ongoing political upheavals is in Belarus, where Alexander Lukashenko, the country’s first and so far only president—he is widely seen as a dictator—has been attempting to crackdown on Belarusian citizens ever since mass protests began following his dubious re-election in early August. To Lukashenko’s surprise and chagrin, most Belarusians supported his opponent, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who has since fled the country with her children.

The anti-Lukashenko opposition consists of hundreds of thousands of people. Protestors have been detained by state police, beaten, and tortured. When it became clear that they would not be deterred by violent reactionary tactics, Lukashenko’s administration began targeting leaders in the uprising. After 200,000 protestors staged a demonstration in Minsk, a Coordination Council was formed to work toward a peaceful resolution to the national crisis.

Most members of the council were arrested or exiled. For some time, Svetlana Alexievich, the Belarusian journalist and historian who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015, was the last original member of the Coordination Council active in Belarus. This was until late September, when Alexievich left for Germany.

Before then, Alexievich had been the subject of a criminal investigation by Belarusian authorities who accused her of undermining national security. After men in ski masks attempted to break into her apartment, Alexievich, one of the most popular Belarusian cultural figures, asked supporters to come to her home in Minsk. Pictures circulated online of Alexievich surrounded by journalists, fans, and sympathetic European diplomats.

It is still unclear how, or when, the unrest in Belarus will resolve. –AR