What can we say about 2021, as a whole? It was a little bit better than 2020, if still not the greatest year in recent memory. It brought us many things: Bean Dad, Bernie’s mittens, Amanda Gorman, variants Delta and Omnicron, Taylor’s Version, but don’t forget Adele, Hot Vax Summer, the immediate end of Hot Vax Summer, Kate Winslet’s vape, the boat stuck in the Suez Canal, the return of Bennifer, the return of the ’90s, a free and glorious Britney, open movie theaters, the Friends reunion, an Asian American muppet on Sesame Street, Harry and Meghan on Oprah, Pete Davidson and Kim Kardashian, Simone Biles somehow being even more of a role model, that Star Wars meme, and, you know, THE VACCINE.

It also brought us a few developments in the wide world of literature. Today, we have reached the top ten biggest literary stories of the year. If you’ve stuck with us this long, bless you. If you’ve just stumbled on this insane list, well, bless you too—and best of luck for 2022.

10. At long last, Jonathan Franzen’s professional reputation overshadowed his personal one.

Before this year, you probably knew Jonathan Franzen as the guy Jennifer Weiner was really mad at, or the guy who spurned Oprah Winfrey, or even the guy who preferred not to do his research on the internet, but what you may not have realized until 2021 is that Jonathan Franzen also writes novels. Blessedly for us all, this was the year that the internet spent more time talking about the fiction of Franzen than the facets of Franzen.

It helped that his new novel, Crossroads, was widely agreed to be excellent. It also helped that Franzen’s public opinions—whose expression the release of his excellent new book necessitated—were widely agreed to be measured and thoughtful. And, as we all know, measured, thoughtful opinions just don’t set the internet ablaze like bonkers and terrible ones do. (Unless we’re talking about Jonathan Chait’s internet.) In a profile in WSJ Magazine, Franzen explained why he didn’t sign the infamous Harper’s letter (“I felt it could be construed as somehow an attack on Black Lives Matter at a moment when that was just not the thing to do”) and why he’s not terribly concerned about the menace of cancel culture (“until people start being sent off to Lubyanka for having said the wrong thing to the wrong person, the risk is probably overblown”).

Speaking to Merve Emre in Vulture, Franzen recommended a number of books by women, which one could read as a rebuke to past accusations of misogyny, or as a genuine expression of admiration for Nell Zink, Christina Stead, and other wonderful women writers. (I choose the latter—it’s a very good reading list.) In the interview, Franzen also explained that he hadn’t read Sally Rooney, but that “People seem to speak well of her.” An extremely non-controversial statement from a man who is now primarily known for writing good novels! –JG

9. Department of Justice sues to stop Penguin Random House from buying Simon & Schuster

This is a “news” story that has stayed news for over a year, and will be giving us headlines well into 2022. It was announced in late November 2020 that Viacom had agreed to the $2.2 billion sale of Simon & Schuster to Bertelsmann, the parent company of Penguin Random House.

This, of course, meant the Big 5 of corporate publishing would now become the Big 4—along with Hachette, Harper-Collins (which bought HMH, btw), and Macmillan—increasing the ever-present anxiety of many in the book world over the threat of consolidation and monopoly. As details of the massive deal began to emerge earlier this year, those concerns only grew, with many wondering out loud about the merger’s impact on the livelihoods of mid-level, non-blockbuster writers.

But almost a year after the deal was announced, the Department of Justice announced it would be filing suit to prevent it from moving forward. As our own Jessie Gaynor reported on November 2:

In welcome news for fans of both books and strong antitrust regulation, the US Department of Justice filed a civil lawsuit today to block Penguin Random House’s acquisition of Simon & Schuster. The complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, details how the proposed merger would “would likely result in substantial harm to authors of anticipated top-selling books and ultimately, consumers.”

Penguin Random House would control close to half of the market for the acquisition of publishing rights to anticipated top-selling books. Penguin Random House’s next largest competitor would be less than half its size. Post-merger, the two largest publishers would collectively control more than two-thirds of this market, leaving hundreds of authors with fewer alternatives and less leverage.

The complaint also gets into the bidding process, giving some recent examples of how competition between houses can drive up advances for the author. “The head-to-head competition between Defendants has allowed authors of anticipated top-selling books to secure higher advances and other favorable terms.”

In addition to its impact on authors, the merger would also make business more difficult for small presses, many of whom rely on Penguin Random House or Simon & Schuster for distribution services.

The suit also brought to light internal documents that belie PRH’s public suggestions that the merger would serve as a bulwark against Amazon’s ever-increasing hegemony over all things book, with PRH CEO Markus Dohle admitting that “he never bought into that argument” and that “one goal of [the merger] is to become better partners to Amazon.”

As promised, the story keeps going: earlier this month PRH and S&S released a joint response to the suit. As Daniel Petrocelli, a lawyer representing PRH and Bertelsmann, told the Times, “The government wants to block the merger under the misguided theory that it will diminish compensation to just the highest-paid authors. That is legally, economically, and financially wrong, and it ignores the vast majority of authors who will indisputably benefit from the transaction.”

The DOJ suit, though it has made things difficult (and embarrassing) for all involved, seems likely to only delay the merger, and we’ll almost certainly have some version of Penguin Random House Simon and Schuster by this time next year. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor in Chief

8. Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo faced mounting allegations that he illegally used state resources to write his memoir.

This year certainly brought a stark reckoning for New York’s former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who resigned after a state investigation led by New York Attorney General Letitia James found him guilty of sexually harassing women on his staff and the FBI began investigating how his office handled data on the number of pandemic-related deaths in New York’s nursing homes. This November brought a new chapter, as New York’s Joint Commission on Public Ethics revoked the permission it had granted last year for Cuomo to write a book, stating that he may have to forfeit the profits he earned from its publication.

Crown published Cuomo’s memoir, American Crisis: Leadership Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic, last October, as the pandemic began a deadly winter surge; even then, the timing seemed off, with Megan Garber pointing out in The Atlantic that the book was one of those that are “poorly aged from the moment they’re published.” A member of the state ethics panel had approved the book project in July, outside of its usual procedure—which would have involved a vote and official authorization—and Cuomo reportedly received a seven-figure advance for it.

In March, as the furor over Cuomo’s handling of nursing-home deaths ramped up, Crown halted promotion of the book, stating that it did not have plans for a reprint. Now, the subject of a state ethics inquiry is whether Cuomo illegally used state resources in the production of the book for his personal profit. The ethical commission certainly thinks so; it released a resolution, approved 12-1, stating that “state property, resources and personnel, including staff volunteers, were used in connection with the preparation, writing, editing and publication of the book.” The New York Times reported that, among other instances, aide Melissa DeRosa “attended video meetings with publishers, and helped him edit early drafts.” Cuomo has rebuked the allegations, stating that “any help that was given was done so outside of working hours on a volunteer basis.” (Okay.) So far, Cuomo has earned $1.5 million from the book and donated $500,000 of it to the United Way of New York, the Associated Press reported. –CS

7. Six of Dr. Seuss’s books were removed from print by Dr. Seuss Enterprises due to offensive imagery. Conservatives cried cancel culture.

Early this year, President Biden omitted Dr. Seuss from Read Across America Day, the White House’s annual celebration of reading. The absence of Seuss’s books, which had heavily featured in both President Obama and President Trump’s Read Across America Days, prompted conservative speculation that progressives had “canceled” Dr. Seuss for “racial undertones” in his books—said undertones being the caricaturish, offensive ways Seuss tended to draw Asians and African-Americans. The next day, on Seuss’s birthday, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the foundation responsible for Seuss’s legacy, announced they would cease publication of six of Seuss’s books. In a statement to the Associated Press, Dr. Seuss Enterprises said the books “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong” and “ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families.”

The books Dr. Seuss Enterprises will let go out of print: And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street!, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer. (Seuss wrote over sixty books under the Seuss pseudonym in his life.)

Though Dr. Seuss Enterprises probably made this move to preserve Dr. Seuss’s legacy, conservative politicians and thinkers swiftly condemned the decision, calling it cancel culture in action. Fox News covered the controversy heavily. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, after saying on the House floor that Democrats were outlawing Dr. Seuss posted a YouTube video of himself reading “Green Eggs and Ham.” Meanwhile, Seuss books surged to the top of Amazon’s print bestseller list.

Conservatives may have had reasons for covering Seuss so heavily other than simply stoking partisan animus. Jon Oliver, in a Last Week Tonight segment, made a compelling argument that Fox News went out of its way to get angry about the Seuss news to avoid talking about the Congressional testimony of FBI Director Christopher Wray: “It’s not hard to see why Tucker [Carlson] would be so anxious to talk about Dr. Seuss this week, because if he talked about Christopher Wray’s testimony about white supremacists participating in the attack on the Capitol, it would have contradicted what he’s been telling his viewers for weeks now,” Oliver said. “So instead, Tucker and conservative media fell back on their classic playbook of distracting from important issues with bullshit culture wars.”

Also, to the conservatives complaining that Dr. Seuss Enterprises is trying to cancel children’s books: physician, heal thyself. –WC

6. Critical race theory became the hot-button topic of (conservative) moral outrage.

This year, we saw a considerable increase in the discourse surrounding critical race theory—specifically in vocalized pushback from Republicans and conservative school boards. In Pennsylvania, the Central York School District made national headlines when the school board decided to ban a list of resources written by authors of color, including the James Baldwin-centric documentary I Am Not Your Negro. However, after students, parents, and teachers protested, the all-white school board reversed its decision.

Specific authors such as Toni Morrison were also targeted in Republican-backed battles. Recently, Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Beloved became a talking point in the Virginia governor race. Writing for the Washington Post, Farah Jasmine Griffin discussed the misguided intention to ban Morrison in order to protect children: “Efforts to ban works like Beloved undermine democracy, even if they aren’t intended to.” In other parts of the country, some teachers were punished or fired for teaching CRT-related materials. The outrage wasn’t limited to schools. Right-wing groups across the nation supported removing antiracism literature from public libraries. The opposition may (wrongly) believe that CRT is an anti-white campaign concocted by Democrats and a vindictive “woke” mob obsessed with “identity politics,” but this theory only highlights how our county’s shallow understanding of history is governed by the pervasive institution of whiteness.

The body of scholarship known as CRT is “the practice of interrogating the role of race and racism in society,” as defined by the pioneering lawyer, scholar, and professor Kimberlé Crenshaw. For many people of color, CRT is a valid framework used to describe the legacy of systemic oppression that is woven into American society. It shouldn’t be controversial to acknowledge the fact that racism exists or that our creed of “liberty and justice for all” is reserved for the privileged few.

As illustrated in Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project (which, unsurprisingly, was widely criticized by right-wing circles and some historians), slavery shaped this country. And it has never really disappeared, as argued in Ava Duvernay’s documentary 13TH. Slavery has simply acclimated to the times, mutating into different forms of culturally and lawfully acceptable oppression. Why, then, does the subject attract such fierce debate? I don’t think any mental gymnastics are needed to land on a conclusion.

Acknowledging the validity of CRT is too frightening, too radical for some people because it directly challenges the mythology of American exceptionalism and equality. CRT is a refusal to bury the sins of the country’s past; it acts as a throughline to the present. In other words, this has all happened before and it will all happen again: our country likes to rip itself apart over anything related to race and/or racism, and the civil rights movement happened so long ago so why are we STILL talking about something that’s ancient history and not EVERYTHING is about race, ok? (That last part was sarcasm, by the way.) –VW

5. Amanda Gorman became the world’s most famous living poet (and sparked some controversy).

The “famous living poets” club is a small one, and in 2021, now-23-year-old Amanda Gorman ascended to its inner circle. Most of the world first learned Gorman’s name when she was selected as the youngest inaugural poet in memory. After reciting her poem “The Hill We Climb” at Joe Biden’s inauguration, Gorman promptly became a best-seller (her two books, The Hill We Climb and Change Sings: A Children’s Anthem, both forthcoming at the time, shot to the top of Amazon’s charts) and a certified sensation.

Since the inauguration, Gorman has performed at the Super Bowl (yes, the Super Bowl of football!); been on the covers of both TIME and Vogue; teamed up with Penguin Random House to launch the Amanda Gorman Award for Poetry; become the face of Estée Lauder; and hosted the Met Gala.

Gorman’s success, along with increasing recognition of young poets of color including Ocean Vuong and Danez Smith, led CNN to declare a “new golden age” of poetry, noting that Poets.org saw an additional one million pageviews in 2021, which the Academy of American Poets attributed at least partly to Gorman’s performance at the inauguration.

Of course, Gorman’s rise has not been entirely without controversy. In an interview with the New Yorker, satirist and noted Hamilton hater Ishmael Reed voiced his displeasure with Jill Biden’s decision to appoint Gorman inaugural poet over US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo.

“What bothers Reed most is the Hamilton-loving Gorman’s ascent to Black Lives Matter icon by executive fiat,” wrote Julian Lucas in The New Yorker. “Can you imagine Fannie Lou Hamer on the cover of Vogue?” Reed wondered.

Controversy also erupted in a more esoteric arena: the world of Dutch translation. In February, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, the translator of the Dutch edition of The Hill We Climb, stepped down after criticism from some poets and journalists that a white translator was selected to translate a work by a Black woman that deals with race.

Rijneveld’s resignation ignited a larger conversation about race, inequity, and the role of the translator. In TIME, Jhumpa Lahiri described the decision as “problematic,” and said that “it goes against what translation at heart really is, which is a bringing together of those who are different, and don’t know one another’s experiences vis a vis language.”

The cover of Vogue, a performance at the Super Bowl, and a controversy that calls into question the very nature of language? Not bad for a poet. –JG

4. Supply chain nightmares upend publishing.

“Supply chain” is probably one of the most overused yet misunderstood phrases of 2021. From a pulled-back, society-wide view, it’s not entirely a bad thing that the pandemic has shown many of us how the simple comforts of daily life rest upon a fragile chain of cheap resources and exploited labor that, per late capitalism’s twin engines of growth and efficiency, is consistently pushed to a breaking point.It’s pretty obvious our habits of immediate and endless consumption are not sustainable—the system, by design, has no margin for error. So how has this affected the publishing industry?

As ably summarized by Walker Caplan in September:

There are two main factors causing the book supply chain issues: a paper shortage and COVID-19. First, the paper shortage. Demand for wood pulp has rapidly increased, in no small part due to the massive amount of cardboard used by online shopping. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of wood pulp has gone up 50.2% over the past year; the cost of paper has gone up 14.2%. For years sawmills have been cutting production due to lack of demand, and when the pandemic hit, they cut production even more in anticipation of less demand. But instead, demand ramped up—and now there’s a major lumber shortage, which is causing delays in the paper-making process as well as sky-high prices. (That’s the reason everyone started hoarding toilet paper.)

Then there’s the pandemic. Quarantine and COVID outbreaks mean that there are many fewer workers in factories, in warehouses that pack and ship books, on shipping docks, and driving the trucks to transport books—causing major delays at pretty much every step of the book delivery process. Plus, high-volume shipping ports overseas are closed due to COVID risk, meaning longer production times as well. These delays build on each other, causing the much-discussed supply chain issue.

As for next year—and as with most aspects of our lives—it’s very hard to say what a new normal will even look like. Publishers, ever at the mercy of their printers, who are at the mercy of the paper supply, continue to change pub dates, and if things continue like this, it will only serve to heighten corporate publishing’s tendency to favor the select big titles at the expense of the many smaller ones. Nobody wins when that happens. –JD

3. Philip Roth biographer Blake Bailey was accused of sexual assault, which led his publisher to abandon a project years in the making.

Let’s start with Philip Roth: controversial; renowned; brilliant; famously and fastidiously image-conscious (evidenced by his public persona along with his lifelong literary project of analyzing his own selfhood); vitriolic in response to his critics, particularly the women he had dated, married, and sometimes mistreated; distrustful of interpretation, especially from anyone who would claim the herculean task of documenting the breadth of his life and legacy. To even take on the project of writing his biography—especially while he was still alive and able to object to just about anything—must, one imagines, involve a particular combination of ambition, determination, and insanity. Blake Bailey showed up in 2012 to nominate himself for the job.

Others had tried and failed before. In 2009, after working with his friend and professor Ross Miller for five years, Roth fired him from the project after they disagreed about its direction. Roth himself had failed, too; he had previously penned “Notes for my Biographer,” a nearly 300-page response to Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir of their marriage, Leaving a Doll’s House, but abandoned its publication at the urging of some wise friends. Bailey, who had previously published biographies on John Cheever and Richard Yates, approached Roth a few years later; following extensive conversations about Bailey’s intentions for the project, Roth offered it to him, as the story goes, as the two rhapsodized over the good looks of Ali MacGraw, the actress who starred in Goodbye Columbus. That detail, like several in this saga, is one of those that seems a little too on the nose to be real.

Bailey started working. His research involved unprecedented access to Roth’s papers, including those that the author had instructed his estate to destroy after his death. He spoke with more than 100 people in Roth’s life, in addition to lengthy interviews with Roth himself; he told Vulture that they had a “nice rapport,” adding that he “did not openly discuss, unless he confronted me, what sort of conclusions I was reaching. I let him do the talking.”

In 2017, he began writing, and Roth died in 2018, of congestive heart failure. W.W. Norton published Philip Roth: The Biography in April to respectful, though mixed, reviews. Roth’s relationship with women was, Pahrul Sehgal wrote, at the center of the book, which she described as “most thoroughly a sprawling apologia for Roth’s treatment of women, on and off the page,” while Bailey remained “strangely reticent on the work.” Other reviewers picked up on the feeling of male complicity that suffused the work; as The New Republic‘s Laura Marsh wrote, “In Bailey, Roth found a biographer who is exceptionally attuned to his grievances and rarely challenges his moral accounting … this sympathetic biography makes him a spiteful obsessive.”

Over the course of the following weeks, a story would emerge that would profoundly change the book’s reception and lead to its abandonment by W.W. Norton. Shortly after the book’s publication, several women accused Bailey of sexually assaulting them; Valentina Rice, who said that Bailey had attacked her in 2015, revealed that she had anonymously emailed her allegations to W.W. Norton president Julia Reidhead in 2018. A week after the email, Bailey contacted her directly to say that the publisher had shown him the note; he denied the accusation and asked her not to pursue it any further. (Rice also anonymously emailed a New York Times reporter, who responded to her, but Rice decided at the time not to reply back.) Additionally, several former students recounted that he had groomed them as a middle school teacher years before; one of them, Eve Payton, said that Bailey had raped her in 2003 and told her that he had been attracted to her when he met her at the age of 12.

W.W. Norton, in response, stopped distribution of the biography and, on April 27, announced it would take the book out of print—an almost unheard of move. The following month, it was picked up by Skyhorse, which proudly brands itself as “[willing] to tackle tough issues that other publishers won’t touch”; the publishing house previously adopted Woody Allen’s memoir after internal protests at Hachette led to its cancellation there.

The string of events has frustrated many of Roth’s contemporaries and scholars that focus on his work. Joel Conarroe, Roth’s friend and former executor, told The New York Times it was a “shame for Philip that he has to be associated with what occurred,” adding, “What troubles some of us is that this affects Philip’s reputation.” Whether or not it directly affects the author’s reputation, the incident has indisputably become another entry in the long story of a complicated legacy. –CS

2. Maybe you heard, but Sally Rooney published a novel . . .

Would it surprise you to learn that it was less than a year ago when we heard the first whisper about Sally Rooney’s latest novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You? It’s true: FSG announced the news in January, the cover was revealed in April, and arguably the biggest (or at least the most relentlessly hyped) novel of 2021 landed on September 7, to the delight and/or discourse of all.

Despite the fact that Rooney only agreed to do a single official event for the novel, the hype machine was in full gear, with anticipation, as Kate Dwyer put it in the Times, approximating “streetwear-drop levels.” Yes, I’m talking about the bucket hat. There was also the tote bag, the pencils, the t-shirts, the umbrella, and the coffee truck. The merch was not just merch, of course, but status, inspiring the mid-level denizens of the literary world to wring their hands after opening the mail.

Emily Bootle nailed the tailspin at The New Statesman: “I might sincerely like Sally Rooney, and therefore instinctively want the tote bag for reasons I cannot fully explain. But I know that using the tote bag will identify me as someone who likes Sally Rooney, and everyone else also understands that I know that. So depending on your view, wearing it either results in me looking pretentious (clearly someone who wants everyone to know she’s read Sally Rooney!) or authentic (clearly someone who doesn’t care that everyone knows that she likes Sally Rooney!). These trains of thought very quickly become tedious for everyone involved.”

For those not in the industry, early galleys were selling for hundreds of dollars on eBay. In the UK, Faber opened a Sally Rooney pop-up shop to sell “copies of the novel as well as Rooney’s previous works, plus a selection of the author’s recommended reads” and “host workshops, book clubs and daily giveaways, including a calligraphy and candle-making class.” Said pop-up shop even came with a mural.

Obviously, people bought it. After three days, Beautiful World, Where Are You? was already Waterstones’ biggest fiction title of 2021. Less than two weeks after its publication, it had already racked up 67 professional reviews, making it the most widely reviewed book in recent memory, more discussed even than Normal People (which after all, did not feature a Rooney stand-in character who hates, just hates, being a famous writer, yum yum yum). Don’t even get me started on Twitter. (In fact, the only person who didn’t have an opinion on Sally Rooney, it seemed, was Jonathan Franzen.)

By the time we got to Israel, it was all beginning to feel like Discourse Mad Libs, but so it goes with Rooney, who for at least 24 hours was decried as anti-Semitic because she declined to allow her new book to be translated into Hebrew by Israel-based Modan Publishing House, in compliance with the BDS movement’s boycott guidelines.

Heaven help us when it gets made into a Hulu show. –ET

1. “Bad Art Friend” blew up the internet, raised questions about the ethics of art borrowing from life, and highlighted a real scarcity of resources in the literary industry.

Yes, you knew it was coming: the Bad Art Friend comes back to haunt us all. Now that it’s no longer the hot topic in your group texts (which will hopefully never be subpoenaed), it’s time to revisit.

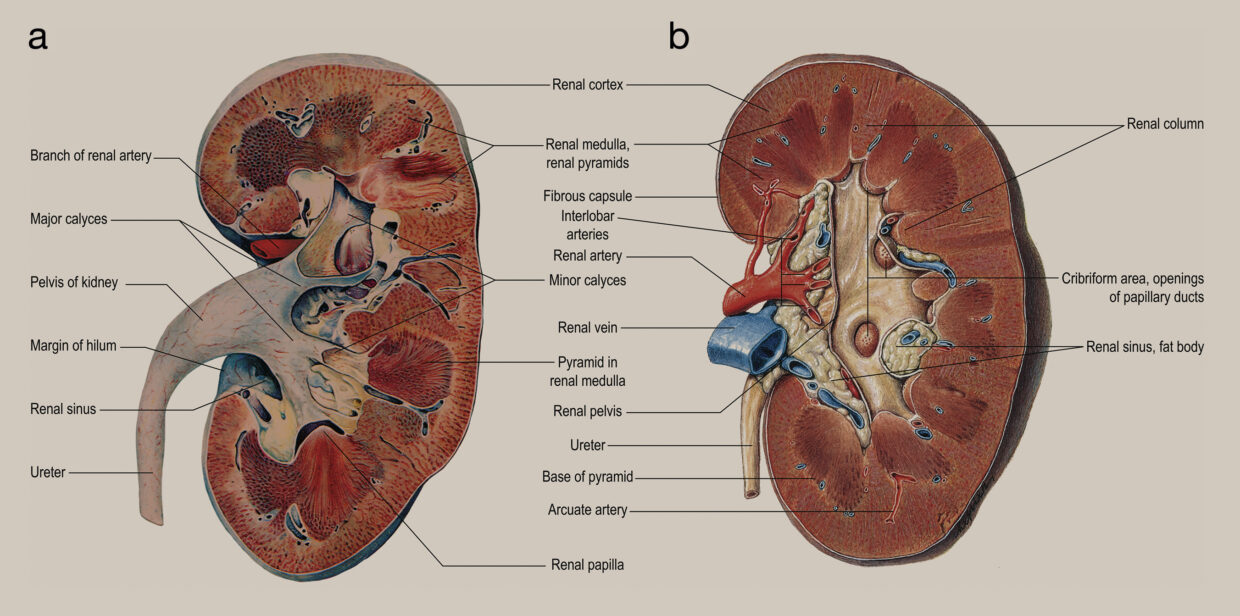

October 5, 2021. It was a Tuesday just like any other. New books were coming into the world. The National Book Award shortlist was announced. But all anyone could talk about was kidneys, or more specifically, Robert Kolker’s New York Times feature, titled “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?”. If you have somehow managed to avoid this chaos, or if you have willfully blocked this debate from your memory, here’s a quick recap: In 2015, a writer named Dawn Dorland donated one of her kidneys to a complete stranger. (For the record, Lit Hub’s official stance on kidney donation is that it’s good.) She also started a private Facebook group consisting of family, friends, and a few fellow writers from the Boston-based writing center GrubStreet—people with whom she wanted to share this journey. One of the things she posted to the group was a very nice letter she had written to the kidney recipient, in which she earnestly divulged some of her backstory, her personal hardships, and her hopes for this unknown reader.

That’s all well and good, but this is where the story gets weird. Dawn was miffed that some of the people who she had thought of as close friends had not responded to her posts. There was one person in particular whose praise and acknowledgement she seemed to hunger for: Sonya Larson, a GrubStreet writer whose work was getting some traction in their literary community. Dawn messaged Sonya, fished for a compliment. They exchanged a few room-temperature texts.

Fast-forward several months and Dawn catches wind of a short story Sonya had written—a story about (you guessed it) kidney donation. If you want the play-by-play, I strongly recommend you read the original tell-all. It contains a lot of tantalizing details. There’s Dawn’s letter, slightly reworded, in Sonya’s final draft. There’s Dawn calling GrubStreet management and the Boston Book Festival in an attempt to discredit Sonya. There’s a lawsuit. There’s Sonya’s group text being subpoenaed. The whole incident has even resulted in a few staffing changes at the organization where they all met.

This certainly isn’t the first time that life has inspired art. (See: most art ever created.) But the ethics seem to get a little murkier when the life you’re borrowing from isn’t yours. Much like the infamous “Cat Person” story before it, Kidney Gate had the literary internet once again asking: Who gets to tell what story?

There have been a lot of takes on this piece. Like, a lot. Even Celeste Ng (of Little Fires Everywhere fame and who apparently runs in the same literary circles as Sonya) weighed in on Twitter to clarify some things. As it goes with The Discourse, everyone had their soapbox. A few incisive people have pointed out that the real winner of this whole ordeal was Robert Kolker, who The New York Times undoubtedly paid a tidy sum for the thousands of words he used to report the story. Other authors have waded into these waters as well. Danielle Evans came in with the good take that this is less a story about morality and art than it is a story about friendship dynamics.

Whether you’re on Team Dawn or Team Sonya, it’s worth taking a step back and considering the background of each of these writers, and the ways that the literary industry as a whole has perhaps been less than welcoming to them. Dawn grew up in rural Iowa, where she and her family lived in near poverty. Sonya, on the other hand, is a biracial Chinese American woman who was raised in predominantly white Minnesota. It will come as no surprise that publishing, much like the rest of the world, can be a cruel place—nearly impossible to break into if you are not wealthy, not white, not based in New York City. As any diversity report will tell you, it’s a serious industry-wide problem.

Perhaps what the Bad Art Friend story reminds us is that if you do not embody these institutionally favored demographics, there are very few spots left for you. More than anything, this piece draws attention to the scarcity of resources that poor writers and writers of color have available to them. You have to fight tooth and nail, pen and kidney, to get to the top. Maybe the literary industry was the real Bad Art Friend all along, and maybe we should try to do better next year. –KY