August 18 – 22, 2025

- The pleasures of lap-swimming at a bargain gym in East LA

- Laurie Stone rewatches Paper Moon

- Angelina Mazza makes the case for Goodreads

Support Lit Hub.

The Ten Thousand Doors of January

Alix E. Harrow

One Person’s Junk Is Another Person’s Treasure

In Brazil, One Man Collects Fragments of Discarded Lives

Lit Hub Daily: September 16, 2019

THE BEST OF THE LITERARY INTERNET

Searching for Women’s Voices in the Harshest Landscape on Earth

Elizabeth Rush on Antarctica, the "Last Male Sanctuary."

How to Be Human in a Time

of Climate Crisis

On Relearning the History of an Earth on the Verge

On Alma Mahler, Muse and Mistress of Fin-de-Siecle Vienna

Cate Haste Considers the Legacy of "a modern woman who

lived out of her time."

Faster Than We Thought: What Stories Will Survive Climate Change?

Omar El Akkad on Our Obligation to Preserve Memories

Helen Phillips on Her Dark Exploration of Motherhood

The Author of The Need on First Draft

Elizabeth McCracken: Remembering Susan Kamil, Friend and Editor

"Susan was always looking out for the safety and happiness

of those she loved."

Can Climate Fiction Be… Hopeful?

Alex DiFrancesco and Ashley Shelby on Writing

Mythology for a New Era

The US Tour That Made Gertrude Stein a Household Name

She Was Always Ready for the Paparazzi

Will It Ever Be Ethical for Athletes to Edit Their Genes?

Françoise Baylis on the Problematic New Science of

"Building Better Humans"

Marching on London with Extinction Rebellion

Thomas Bunstead on the Pilgrimage from East Sussex to London

On the Rare Decency of

Susan Kamil

John Freeman Remembers One of Publishing's Great Editors

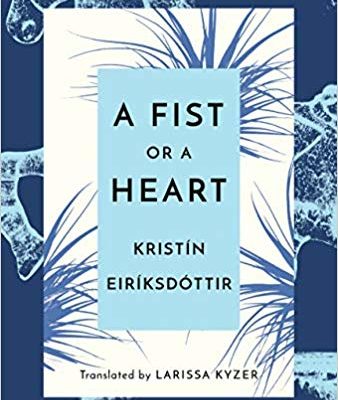

A Fist or a Heart

Kristín Eiríksdóttir (trans. Larissa Kyzer)

Lit Hub Weekly: September 9 – 13, 2019

THE BEST OF THE LITERARY INTERNET

Page 1339 of 1866