One Person’s Junk Is Another Person’s Treasure

In Brazil, One Man Collects Fragments of Discarded Lives

Bagé, in Porto Alegre, would be a street like any other in the neighborhood of Petrópolis. It would be, were it not for house number 81. A sliver of chaos in the cosmic order of Bagé. A triangle in the middle of a row of squares. A raw protest against consumer society, disposable and implacable. Number 81 Bagé Street is the lair of a little man, not even five feet tall, frail as a sigh: Oscar Kulemkamp. Inside the house lie fragments of an entire city.

Nobody knows when Oscar Kulemkamp initiated his resistance. He spends day after day on a pilgrimage through the streets of Porto Alegre. He began by rescuing amputated stools and giving them back their legs. Eventually he took on the mission of gathering up bits and pieces of the city. He goes from trash bin to trash bin, as far as he can, retrieving chunks of wood and pipe, broken fans, cracked vases, abandoned toys. It is an arduous task, because he’s a lone combatant against an army of 1.3 million people who toss out the remnants of their lives every day.

Oscar Kulemkamp has reclaimed these cast-off lives and saved them from the landfill of oblivion. That’s how the simple house where he raised seven children was transformed into a lair. Remnants of existence have gradually taken over the rooms of his home. When the inside overflowed, he began occupying the front yard, the breezeway, the backyard. When every space was filled, he began hanging things from the branches of the chinaberry and avocado trees. After the trees, it was the sidewalk’s turn. Oscar Kulemkamp’s cocoon would not stop growing. Now the windows are covered by obsolescent things, and he can only penetrate the house by snaking through a tunnel of remains.

If he weren’t reinventing the world, Oscar Kulemkamp would merely be the owner of a life that had departed. Like his wife did, four years ago. And a daughter, lost to cancer. For most of his 85 years he was a waiter, but the tables he served no longer exist. They are names from the past, thin air, like Sherazade Restaurant. Stories no longer told, streets now gone, characters that inhabit only cemeteries.

He emerges from his timeless tunnel like a little mole. He is wearing cheap clothing, threadbare and dingy from the dust of days. He’s deafer than a doornail, as he puts it. If he didn’t salvage the remains of other people’s existences, he’d only have the two sons who share his cave, one who lives in darkness and never leaves home, one who sometimes threatens to kill him. And the four married children who don’t understand his obsession. And the two cats who wage never-ending battles with the squadron of rats who stalk this elderly inhabitant of Bagé.

Oscar Kulemkamp has stitched his patchwork from other people’s lives, from the rubbish of other people’s lives. Cards never sent to him: “I prayed so hard to spend this Christmas with you.” Manuals for objects that never belonged to him: “Please note: this television set offers a number of innovative features. To understand and enjoy them all, it is essential that you begin by reading the instruction manual.” Packages he never ordered: “Services paid for by check will only be delivered after the check has cleared.” Strangers’ IDs, business cards from professions never to be his. Magazine pages, leaflets, prayer cards. A photograph of a royal family, a picture of snow. Even a piece of paper that reads “I’m happy!” Christmas bulbs from a tree that didn’t glow in his December.

In Oscar Kulemkamp’s hideout, deflated balloons from the birthday party of a child he doesn’t know adorn every day of his life. A decoration some other child made from Popsicle sticks—later abandoned by the mother who received it—is housed in the living room cupboard. Twisted, broken, beat-up dolls sit in a row. And rejected little girls in smiling photos hang there like beloved granddaughters.

The neighbors are alarmed by the relentlessly expanding cocoon, by the shadows—half-tree, half-garbage—that advance into the street. One woman living nearby asked the Department of Urban Sanitation to do something about it, and they carried off part of Oscar Kulemkamp’s treasure. He was driven to such despair that no one else has had the courage to protest. A sympathetic neighbor now keeps a hose at hand, so the day it all goes up in flames, he can at least save the man entrenched in his cave. Then Oscar Kulemkamp can resume his endless journey to save the bits and pieces of the city.

When he appears from within today, skeptical and smiling, Oscar Kulemkamp hurries to explain that one day, one day soon, he’s going to carry it all off to build a beach house. A paradise where weary dolls, photos of children no longer loved, and cards from birthdays past do not turn into trash. A world where neither things nor people are disposable. Where nothing and nobody becomes obsolete once it is old, broken, or bent. A world where everyone is of equal value, and no one’s lot is a garbage bin.

Number 81 Bagé Street is the castle of a man who has invented a world without leftovers. By assigning value to things that have none, Oscar Kulemkamp values himself. By collecting cast-off lives, Oscar Kulemkamp salvages his own. Perhaps this is the mystery of house number 81. And perhaps this is why it is so frightening.

___________________________

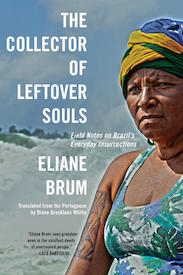

From The Collector of Leftover Souls: Field Notes on Brazil’s Everyday Insurrections by Eliane Brum, translated from the Portuguese by Diane Grosklaus Whitty. Used with permission of the publisher, Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2019 by Eliane Brum. English translation copyright by Diane Grosklaus Whitty.

Diane Grosklaus Whitty has translated The Collector of Leftover Souls: Field Notes on Brazil’s Everyday Insurrections by Eliane Brum, as well as Activist Biology by Regina Horta Duarte, and The Sanitation of Brazil by Gilberto Hochman. She has also translated prose and poetry by Adriana Lisboa, Marina Colasanti, and Ma´rio Quintana, among others. Her translations have appeared in the Guardian, the Lancet, History Today, and Litro. She lives in Madison, Wisconsin.