Our Favorite Lit Hub Stories From 2021

The Best Writing at the Site This Year, According to Us

From essays to interviews, excerpts, blog posts, and reading lists, we publish around 500 features a month. And while we are proud of all the 6,000+ pieces we’ve shared in 2021, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of the pieces we loved best on Lit Hub from this long, dark year.

“The Long Unpredictable Life of Art” by Francine Prose

During the pandemic, Prose taught a class at a men’s maximum security prison as part of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). The class was remote, without video, the men coming up to a microphone to participate. One of the stories she taught in the class was “Gold Coast,” by James Alan McPherson. “I met Jim McPherson in 1967, in a writing class at Harvard, where I was an undergraduate and he was attending Harvard Law School,” she writes in her essay. “He was writing ‘Gold Coast’ in that class, that semester.” McPherson was so good that Prose wrote nothing all semester (“We were at an age when another writer’s talent can make you want to quit forever.”). A thin through-line connects her memories of McPherson, the dedication of her incarcerated students, and their engagement with the text, and… crying? Some stories make us cry, for no reasons and for all reasons. It is because of the “long, unpredictable life of art.” This is a beautiful, meditative essay on what it means to be a reader. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

“The Complicated Grief of Trying to Adopt a Child” by Sarah Sentilles

I’m a big fan of Sarah Sentilles. Her 2017 book Draw Your Weapons—a memoir-reported-theology-visual culture mash up about war, weapons, PTSD, and art—is a book I continue to think about today. This year she published Stranger Care, a memoir about her decision to adopt a foster child and the unrelenting heartbreak of that process. This essay, which felt both part of the book and wholly new, lays bare Sentilles love for a three-year-old girl named Coco alongside the heartache wrought by the complicated process of adoption… and a moose that’s wandering in her neighborhood. Bring tissues. –EF

“On the Power of the Unlinked Short Story Collection” by Chris Stuck

We publish a lot of reading lists on Lit Hub, and usually there’s a book I haven’t read that I get to add to my TBR pile. But every so often we publish a reading list where I have read every book on there and it reminds me why these books are so good (and sends me back to them). Stuck’s reading list on unlinked story collections is an ode to the type of book, he argues, that isn’t published as often these days because The Publishing Industry is looking for stories that act like novels. These collections are more like albums, each story is doing their own thing in its own way, and doing it brilliantly. After we published this, I reread both James Alan McPherson, Hue and Cry and ZZ Packer’s Drinking Coffee Elsewhere (and, of course, Stuck’s Give My Love to the Savages). –EF

“What the Dixie Chicks Meant to Me as a Teenager in Namibia” by Rémy Ngamije

As a teenager, Rémy Ngamije’s dream was to leave Namibia. His family had immigrated from Rwanda (via Nairobi) in 1996, landing in the small, boring town of Windhoek. “In the early 2000s, whatever happened to be cool in the world was lukewarm when it arrived in Namibia.” And so, it was the Dixie Chicks that Ngamije heard on the radio and fueled his desire for “wide open spaces… room to make mistakes… new faces.” It’s then ironic that almost two decades later he finds himself back in Windhoek when COVID begins. “Much like my teenage years, when it felt like Namibia received things when they were no longer en vogue, it is scary and disheartening to realize in this desperate fight to contain the coronavirus’s spread and reach herd immunity, we are most certainly going to be one of the last countries to receive vaccines.” Ngamije’s mediation on home, migration, and yes, The Dixie Chicks as pandemic comfort is a surprisingly beautiful read. –EF

“Private Practice: Toward a Philosophy of Sitting” by Antonia Pont

This marvelous essay by Antonia Pont is perhaps one of my favorite things we’ve ever published at Lit Hub, not least because it is about such a humble subject: yes, sitting. What is there really to say about sitting-as-practice? An awful lot, as it turns out. With an inviting mix of amiable erudition, well-earned wisdom, and absolutely spot-on comic timing, Pont does, indeed, fulfill the promise of the title. Smart, funny, revelatory… we are all better for this perfect philosophy of sitting. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

“Searching for the Sacred on a Planet in Crisis” by Megan Mayhew Bergman

“Perhaps the planet’s failing health calls for new belief systems and spiritual practices that promote harmony and balance with the natural world.” This gorgeous essay by Megan Mayhew Bergman is an important reminder that even as we struggle to grasp the enormity of the changes we have wrought upon our planet, so too do we each struggle to find meaning in the small moments of our lives. If there is grace in this broken world, Mayhew Bergman seems to suggest, if we are to salvage hope and purpose from these dark times, it will be through acts of witness and testimony that move us beyond our old and inward human-centered view of life. –JD

“A Dinner in France, 1973: Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, and a Very Young Henry Louis Gates, Jr” by Harmony Holiday

“You can tell they’re outside of the US because they don’t euphemize, they know the heart of the crisis of Americanism.” Part anecdotal history, part travelogue, part contemporary polemic, this Harmony Holiday essay will linger with me for a long time. Holiday sets the incredible scene in 1973 when a young Henry Louis Gates Jr. traveled to the south of France to interview Josephine Baker and James Baldwin, and moves from there through meditations on Blackness, exile, and all this nation has lost through its foundational cruelties and delusions of justice. Yes, there is lamentation here, but so too is there joy. –JD

“The Ambiguous Loss of (Probably) Not Selling My Novel” by Danielle Lazarin

Writers talk a lot about rejection in general terms. We will allow, from a safe distance, that rejection is a constant of the trade. It’s rarer to hear from a writer in the middle of the kind of slow, ambiguous rejection that comprises so much of the atmosphere of publishing. Danielle Lazarin’s essay is a beautiful meditation on that limbo, written when her novel had been on submission for 16 months. She grapples not only with the strange liminal space between hope and grief, but also our hunger for redemption narratives, and the double-edged sword of external validation. One to bookmark, and return to often. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

“Is There a More Interesting Way to Talk About the Blurry Line Between a Writer’s Life and Their Fiction?” by Sara Martin

I wish I could say I have never said yes to something because saying yes seemed more like what a character in a short story would do than saying no—but I don’t want to lie to you. Luckily, Sara Martin put words to this phenomenon. “How much of your life,” she asks in this essay, “has been determined by fiction?” She considers both the conscious pursuit of situations that remind us of beloved stories as well as the way in which those stories blur with memories. After all, is the life of a character read and reread in childhood any less a part of us than an actual person? The desire to enter a story isn’t limited to childhood, of course. “There is a kind of bibliomancy, the use of books in divination, to being a reader of fiction,” Martin writes. I love this exploration of reading as roadmap and surrogate memory. –JG

Whither the Plain Female Protagonist? On “Great Beauty in Literature” by Lucinda Rosenfeld

A fun thing to try, as a woman, is saying “I’m not beautiful” in mixed company. The speed and vehemence with which everyone will rush to assure you that you’re mistaken will tell you a great deal about the incredibly outsized value we place on female beauty. Lucinda Rosenfeld’s wonderful essay explores this phenomenon in literature. Why is it so rare, she wonders, for a female protagonist to be simply not beautiful? “The instinct to render fictional heroines ‘hot,'” she writes, “has both a long history and one which continues to this day.” I loved reading Rosenfeld’s exploration of the missed opportunities of failing to look deeper at beauty, or the lack thereof. –JG

“How The Power of the Dog Eviscerates the Myths of the Old Western” by Michelle Nijhuis

“The sun may have set on the Western genre, but we still need reminding that those with the biggest hats have the fewest cattle.” My favorite piece on my favorite film of 2021, Michelle Nijhuis’s multi-pronged essay considers the depiction of masculinity and queerness in Jane Campion’s adaptation of Thomas Savage’s subversive 1967 novel, The Power of the Dog, as well as the way in which the Western genre’s masculine ideal has both expanded and curdled in the decades since its publication. The essay’s final paragraphs make for particularly chilling reading. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor in Chief

“Check Out the Original 1851 Reviews of Moby-Dick” by Book Marks

“Thrice unlucky Herman Melville! … This is an odd book, professing to be a novel; wantonly eccentric; outrageously bombastic…” As someone who spent a sizable chunk of 2021 finally working my way through Melville’s leviathan whaling opus, I was tickled to discover this selection of reviews—some ecstatic, some derisive—from the fall and winter of 1851. The prickly comments from Moby-Dick stans and haters underneath the piece are, as you would expect, also a hoot (special shout-out to the reader who declared, quite rightly, that “there is no reason to poop on Dostoevsky”). –DS

“An Essay About Tiny, Spectacular Futures Written a Week or So After a Very Damning IPCC Climate Report” by Lucas Mann

“In this one, she never knows hunger or pure, crystalline fear. In this one, she does.” I was so very moved by this beautiful, dreamy, and quietly terrifying lyrical essay, built around a refrain, in which Mann imagines various futures—near and distant, cataclysmic and utopian, cozy and expansive—for his young daughter. Mann lays bare the comforting fantasies and nagging fears that swirl around his mind, as a young husband and father, when he thinks about his beloved wife and child. It’s a gorgeous, vulnerable, disquieting piece, one I’m certain I’ll revisit often in the years ahead. –DS

“What Happens If You Get Sucked Into a Black Hole?” by Jorge Cham and Daniel Whiteson

Never have I ever clicked on a Lit Hub piece so quickly! This is one of those burning questions I have that I have never thought to google. Black holes, like quicksand and anvils, are one of those things that come up in cartoons that I always thought I might encounter someday. So far, so good, but it might be a smart idea to learn a little something about these ultimate voids—just in case. Personally, I have always found science to be quite poetic, and this piece is no exception. For example, I have now learned that while blackholes appear to the eye as exactly that, the supermassive ones might have a bunch of space trash (gas, dust, etc.) swirling around, waiting for their turn to get sucked in; the speed at which this space trash spins around actually rips it apart, emitting a lot of energy, or a lot of light. This means that really big black holes might actually have the brightest light in the universe around them. This piece is also a delight to read because the writers are fun about things like getting ripped apart, or “spaghettified.” Science! –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

“Hanif Abdurraqib on What It Was Like to Work at a Chain Bookstore” by Hanif Abdurraqib

The world would be a much better place if everyone had to experience working in customer service. Customers mostly suck. People mostly suck. Except for Hanif Abdurraqib, and the stranger named Steve he befriended one day at the shop. It would not surprise readers to know that the writer—author of Go Ahead in the Rain—spent a lot of his time at the chain bookstore in the music aisle. In this sweet piece, he describes the comfortable unfolding of friendship between himself and this fellow music lover, an old man, a widower, the engaging voice on the other end of the telephone. Of their bond, he says: “I learned to be a critic from people like Steve, who chose to meet me where I was and talk to me about a shared passion.” I, for one, am grateful for their meeting. –KY

“What Is Revealed by the Family Stories That Go Untold?” by Kei Miller

Writers love gossip. Writers love secrets. Family secrets are a particularly juicy subsect, ripe with possibilities for storytellers. (That’s the author’s instinct in you, isn’t it? To want to spill all the beans and let all the cats out of all the bags!) Every family has its skeletons in the closet, but those skeletons are rarely like any others. And what happens when you only get a little bit of the story—just a bone and not the whole body? In this gorgeous, incisive, and personal piece, Kei Miller (author of Things I Have Withheld) gets into how to talk about the things we were never told. Listen to this: “Maybe all that a family is, is the stories we do not tell. Maybe all that a family is, is the shape of its silence.” –KY

“How the War on Terror Became America’s First “Feminist” War” by Rafia Zakaria

Remember those two weeks in September, when the story of the US military leaving Afghanistan was overwhelmingly framed as a crisis of feminism, as if America… actually… cared about non-white, non-American women? Rafia Zakaria, attorney and author of Against White Feminism, delves into that subject here, starting with Zero Dark Thirty and the women who played a part in capturing bin Laden, then moving on to the “liberation lie” of the War on Terror: “Caught in its fevers, American feminists did not question loudly enough the wisdom of exporting feminism through bombs and drones.” A sobering but essential read for making sense of one of the biggest stories of the year (and past two decades). –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

“The Work of Home: Cleaning, Writing, and Communing with Ghosts” by Laura Cronk

“It feels tired to try to say anything about [housework],” Laura Cronk writes, and yet she has written the most untired piece about housework I’ve ever read. Published in February, aka month 11 of lockdown, this essay—about gendered labor; ghosts and visions; the Fly Lady, a weird staple of my childhood in the Bible Belt; and, yes, the pandemic—gave me language for so many things on my mind in Month 11 (“I think the gendered part of my lizard brain can’t help itself. A pandemic is running its scythe through the country and I must keep working”)—but also traveled far beyond its original premise, like every truly great essay. Pair it with this great piece by Melissa Febos on the origins of the word “slut.” –ES

“What’s Missing Here? A Fragmentary, Lyric Essay About Fragmentary, Lyric Essays” by Julie Marie Wade

I mean, the title of this one says it all. Simultaneously a manifesto on lyric essays and a love letter to teaching lyric essays—while also, of course, being a lyric essay—this one strikes a lot of chords for me. “The hardest thing you may ever do in your literary life is to write a lyric essay—that feels finished to you; that you’re comfortable sharing with others; that you’re confident should be called a lyric essay at all,” writes Julie Marie Wade. If that’s music to your ears, so too will be this piece. –ES

Winning the Game You Didn’t Even Want to Play: On Sally Rooney and the Literature of the Pose by Stephen Marche

Love it or hate it (and I loved it), this essay by Stephen Marche deserves your attention as he attempts to figure out just what is happening to the tone of contemporary literature, which—have you noticed?—is cool, collected, and above all careful. Marche notes a shift in dominant literary sensibility from writers of the Voice—”distinguished by the distinctness” of their style—to writers of the Pose, whose deeply depersonalized prose could be described as “language trying not be language, with the combed-through feeling of cover letters to job applications in which a spelling mistake might mean unemployment.” From where did this mode of writing emerge, and how are we to understand it? Whether you have a passing familiarity with, or a thorough appreciation (and strong opinion) of, this phenomenon, Marche’s argument is fascinating, engaging, and assigns order to chaos. It’s worth reading. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Taking a Much-Needed Road Trip to Italy, Texas by Andrea Bajani

This essay holds so much. On the surface, it is the story of attempting to build a home and a language for a son that exists between cultures—in this case, American and Italian. In Bajani’s telling, this story becomes a subtle, complex reflection on the ways that language constructs our lives and influences our view of reality itself. As he writes, “Dante and Baudelaire have taught us that you knead the world with words, and it’s truly the world. The world we see with our hearts isn’t any more true or false than the world we see with our eyes.” Culminating in a road trip to Italy, Texas, a place that encapsulates this relationship between heart and place, Bajani’s essay is a moving look at the world of a family. –CS

From Construction to Teaching: Seven Writers On Their Day Jobs by Emily Alexander

How often, especially on the internet, do you hear an honest accounting of how writers earn their income and whether they actually like it? For this piece, Emily Alexander corralled a number of writers into doing just that, and their contributions—from a bartender, social worker, pharmacist, construction worker, and others—are insightful, enlightening, funny, and remarkably forthright. Writers are the best observers: in my favorite mini-essay, Chessy Normile, an administrator in New York City, notes that, “Language in an office goes haywire. Sometimes I’ll be in a meeting and everyone’s talking about skeletons. They’ll say, “Chessy, can you get a skeleton to me by EOD?” and I’m like “. . . yes.” This piece felt like a conversation you could overhear in the early morning hours at a bar—a moment of connection at a time when I’m not taking those for granted. –CS

The Only Living Black Man in New York: On an Overlooked, Subversive Sci-Fi Story by W.E.B. Du Bois by Gabrielle Bellot

This essay by Gabrielle Bellot was an insightful learning experience. I was familiar with Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk but had no idea he’d made a foray into sci-fi. Du Bois’s “The Comet” centers on a Black man named Jim, who finds himself in Manhattan on the day a comet is supposed to illuminate the city skyline. Jim works as a “messenger” and is sent into underground tunnels to retrieve important papers. However, he gets trapped underground as the comet passes, inadvertently saving him from death by noxious gas. Jim emerges and searches for survivors. He bumps into a white woman named Julia and they think they’re the last two people alive. However, this all changes when Julia’s father and a group of white men arrive. By some miracle, Jim escapes a possible lynching and eventually is reunited with his family, who have also survived. Bellot’s in-depth analysis of the short story is smart, sharp, and enlightening, highlighting the lasting relevance and echoing truths of “The Comet.” She writes, “A hundred and one years later, as the systemic murder of Black Americans continues to be an all-too-banal evil, I think of Du Bois’ subtle genius here, capturing the way that racism, that death-shadowed thing, can perhaps never truly leave America.” Du Bois’s short story is at once ominous and hopeful, which Bellot expertly examines. –Vanessa Willoughby, Assistant Editor

How Audre Lorde’s Genre-Blurring Zami Spoke My Truth Into Existence by Jamika Ajalon

Audre Lorde is a literary touchstone for many writers, readers, and activists. This is evident in Jamika Ajalon’s essay, which is a stirring portrait of an artist who discovered that she could—and must—move beyond the boundaries of societal norms in order to honor her inner truths. Ajalon cites Zami as a critical text to her self-actualization, praising the author for her groundbreaking insight: “Lorde both named and gave a blueprint for a way of writing our existence, our truth.” Ajalon’s essay also describes the vulnerability of unbridled romance and love, of suddenly losing yourself to someone and forever capturing the moment in a photograph. The discussion of representation (and its limits) is honest and hits on the tension between society’s flattened ideals of “acceptable” Black identity and the many nuanced, underrepresented narratives that make up the Black community. The repeated images of fire, flames, and burning are smartly employed. Ajalon’s essay may be on the shorter side, but her prose is confident and commanding. –VW

How My Passion Project Led to Burnout: On the Bittersweet Rewards of Creative Risks by Leigh Stein

Leigh Stein’s Self Care is a biting, satirical novel about girlboss culture, capitalism, the wellness industry, and white feminism. When I first read the novel, I was hooked by Stein’s sharp humor and compelling narrative style. The female-founded company depicted in Self Care is entirely fictional but exhibits shades of real-life companies that were initially touted for their “women first” mantras and declarations of inclusivity only to be exposed for adopting the very same toxic, emotionally abusive, unsustainable practices that plague male-dominated corporations. We’ve all heard the saying, “There’s no ethical consumption under capitalism,” and Stein’s novel shows how under the rule of patriarchal capitalism, feminism can be exploited and commodified. Lo and behold, when I stumbled upon a Twitter thread written by Stein that detailed the challenges of running the literary nonprofit BinderCon, I knew she could expand this experience into a full-length feature and provide valuable insight for Lit Hub readers. This essay pulls back the curtain on what it means to be a working writer, alternative literary communities, and burnout. Stein’s honesty is much appreciated, and she doesn’t sugarcoat the mental, emotional, physical, and financial commitment of attempting to form a grassroots alternative to big-wig, fully funded organizations. Her essay illuminates how the writing and publishing industry can be quite inaccessible to those who don’t have the privilege of wealth or access to disposable income. And yet, despite everything, Stein’s essay ends on a hopeful, positive note: it’s better to have tried and failed than to have not tried at all. –VW

“Maybe More People Should Have Writer’s Block.” In Which Joy Williams Responds to Our Questions Via Typewriter by Joy Williams

I mean, come on. It’s charming. I am charmed. On the occasion of her new book, Harrow, Joy Williams elected to respond to our questions on her Hermes 3000 typewriter (with seafoam-colored keys) and send them back to us by snail mail. That would be delightful enough, but her answers themselves are also perfectly irreverent, particularly in this day and age of careful, encouraging author statements. I love the way she talks about writing, and interviewing, and the “weird beauty” of art, and whether more people should have writer’s block. (Probably they should.) –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Why Does Lionel Messi Ignore the Ball for the First Five Minutes of a Match? by Simon Kuper

Like many soccer fans, I am fascinated by Lionel Messi. He looks like your cousin who is killing time working as a used car salesman before he decides what he wants to do with his life; he plays like a god. (Actually this is one of the many things that make him better than Ronaldo, don’t @ me.) This piece is almost as fun to read as Messi is fun to watch, which is saying something. –ET

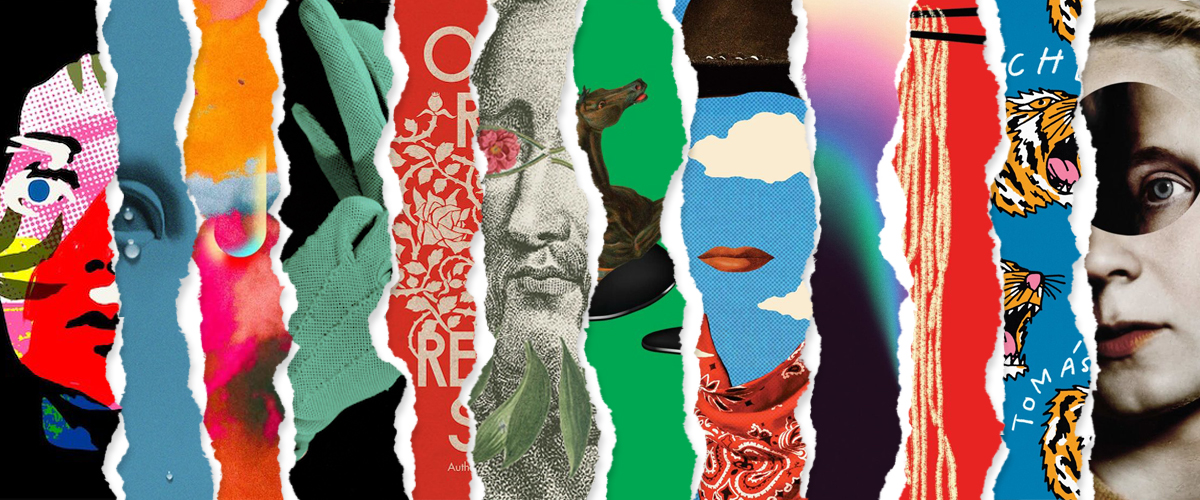

The 101 Best Book Covers of 2021 by Emily Temple

That’s right, I chose this last year and I’m choosing it again. And yes, I know it is technically by me, and I’m sorry about that, but this is always my favorite end of year feature (to read and to put together) and in truth I’m just the organizer—what’s really of value here is getting to see not only the many (101!) engaging, beautiful, funny, and downright odd book covers that have been produced over the last year, but also getting to hear professional designers’ takes on them. I’m grateful, as ever, for the contributions of all these artists to our lives and bookshelves. –ET

Puncturing a Dream: On the Dark-Edged Fantasy of the Ballerina and Traditional Femininity by Rachel Kapelke-Dale

The essay by Rachel Kapelke-Dale is a sharp look into the darkness lurking underneath the fantasy of ballerinas, and the wider traditional ideals of femininity that underpin that fantasy. Kapelke-Dale uses her own experiences as a dancer, and a novelist writing about ballet, to consider the ways in which this dangerous fantasy begins in childhood, and continues as the years go on, masking the physical, mental, and emotional toll that most dancers endure. She writes, “As I probed my own nostalgia, I started to get angry, but my anger was wild and unfocused. I didn’t know exactly what I was mad at. All I knew was that I wanted to puncture this dream, to disrupt it.” And in her disruption, she lays bare the empty promises of such fantasies, instead pushing herself, and her readers, toward new terrains of dreaming. –Snigdha Koirala, Editorial Fellow

The Work of Living Goes On: Rereading Mrs Dalloway During an Endless Pandemic by Colin Dickey

As Colin Dickey points out, Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway is deeply concerned with how any kind of moving on can happen after a large-scale loss—from war, from influenza, from their repercussions. Reading it during the the ongoing era of COVID, Dickey writes, “Woolf understood that a dystopian future would not look like The Hunger Games or The Road so much as it would the everyday, banal world of Before, shot through now with the dead and their ghosts—where everything is the same but all is changed, changed utterly.” Grappling with how one should—or rather, how one can—live after a tragedy, as Woolf does, Dickey offers a reading of Mrs Dalloway, inflected with the heavy weight of the past two years, and surely, of what’s to come. –SK

Defamiliarizing the Mother Tongue: On Immigration’s Impact on Learning and Losing Language by Julie Sedivy

Julie Sedivy’s essay considers the ways in which the defamiliarization of Czech, her mother tongue, offers possibilities in writing. Inflected with the grief of losing a language, or slowly having it to recede to second place, Sedivy emphasizes the ways in which Czech still remains her mother tongue, explaining that it is “the language in which the dramas of my childhood unfolded. My most unruly passions and rages, not yet restrained by maturity or training, were expressed in this language.” And within this tension—of having Czech as a mother tongue, yet on the cusp of losing, or almost losing it, Sedivy finds a liminal, creative space. Considering the mood and texture of both languages, she offers us a porous, liquid relationship to language. –SK

The Mistake No Dialogue Writer Should Ever Make by Dan O’Brien

It can be a struggle to write naturalistic dialogue—and once you’ve done it, there’s the question of how to edit, when life’s conversations can be meandering and undramatic. How to use speech to gesture at the unspeakable, as Dan O’Brien puts it? In this brief and action-packed piece, O’Brien lays out the terms of successful naturalistic dialogue; dispels beginners’ myths; and dispenses actually practical suggestions. Here’s a single sentence: “Pronouns in naturalistic speech are often implied; relatedly, don’t fake urgency by stating a character’s name repeatedly; try to make your wells and you knows mean something; never echo a line or phrase at the end of a scene for dramatic effect.” O’Brien crams a masterclass into a few hundred words. –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

How the Culture of the University Covers Up Abuse by Sarah Ahmed

“My task in Complaint! is relatively simple,” writes Sara Ahmed in her new book. “I listen to, and learn from, those who make complaints about abuses of power within universities.” In this particular essay, Ahmed maps the relationships of the university and the ways that its structures can silence and bind. Ahmed trains her gaze on “collegiality,” the protection collegiality affords, and the university system as a “web of past intimacies” that insulates beloved members from critique. What is it about the university that makes it a breeding ground for abuses of power? Ahmed will tell you. –WC

Ann Patchett on Creating The Workspace You Need by Ann Patchett

Simple and miraculous: in this essay, Ann Patchett tells the story of her changing writing process, from writing anywhere (which strained her body) to using an ergonomic keyboard and walking desk. It’s an everyday tale of a writing life, but it’s heartening—reminding the reader that adapting to new circumstances, especially in one’s creative process, is a gain rather than a loss. –WC

Terry Tempest Williams on the Loves (and Appetites) of the Great Jim Harrison by Terry Tempest Williams

I loved this memoriam of Jim Harrison, and I loved it even more for the fact it’s the intro to his Collected Poems. One of the most human, nuanced, honest depiction of loving a flawed person that I’ve ever read. It is an example of how to encompass someone in their fullness instead of just the good or the bad, the black or the white. Terry Tempest Williams admired and respected Jim Harrison, and also was demeaned by him, also felt confused by him, also wished he was different. An example, for us who love flawed men, which many of us do, in how to talk about them and how to talk to them, like her letter she wrote to him after he intentionally disrespected her at a conference they spoke at, words I’ve been thinking of since I read them: “You spoke. I became mute. Every woman in that audience recognized my silence as their own.” This piece is about Jim Harrison, but it isn’t really. It’s about Terry Tempest Williams, and it’s about women who love. This essay felt like one of the truest examples I’ve read of wanting someone to be both culpable, and also forgiven, and is a lesson in humanness and love that all will take something from. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Do Fictional Critiques of the Wealthy Ever Really … Work? by Andrew Martin and Benjamin Nugent

Two writers, talking about Gatsby. One is speaking from a world without riches, and upon reading the novel parts his hair a certain way and emulates its main character in a certain way, whereas the other goes to private school down the road from Princeton, and knows enough to rue the idea of emulating Gatsby. This take on The Great Gatsby was new, and particularly modern in how it reflected our inundation with depictions of wealth, in all its glory and all its greed, gore, and distance from many of our lives. –JH

On Grit: How Cheryl Strayed Learned to Ride Into Battle by Debbie Millman

It’s been almost ten years since the publication of Wild, but Cheryl Strayed’s voice is still welcome to me. It is especially great to hear her speak of her memoir and mother and that specific time in her life. I loved her focus on the word “grit”—I’ve been experiencing a similar focus on the word “fight” since Miriam Toews’ Fight Night came out—and how a term like that can summon life behind it. In this interview, Strayed speaks of creativity and making big things, and the grit that got her here. –JH

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.