The 40 Best Literary Adaptations to Stream Right Now

It's Like Books On Your Screens!

With nowhere to go in the evenings, I’m finding myself watching more TV and movies than ever before—and as we all know, the best TV and movies are based on books. Yes, it’s true. So which to pick? And which to pick that I can watch with the subscriptions I already have? In case you’re asking yourself the same questions, I looked through the current offerings of Hulu, Netflix, and HBO GO (not Prime Video, sorry, save for one exception) and picked a few of my favorites, in no particular order. What are you watching next? (And what did I miss?) As ever, add on at will in the comments.

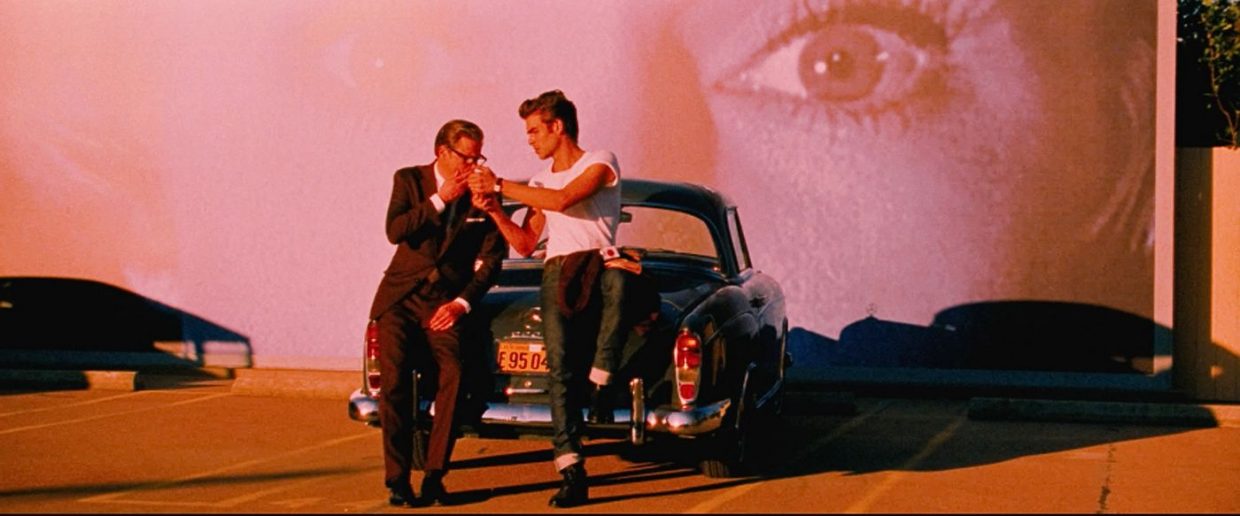

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

Based on: The Talented Mr. Ripley, by Patricia Highsmith

Streaming on: Netflix

A truly perfect film based on a truly perfect novel—though this adaptation manages to improve on the book’s ending, which is fairly incredible. This is also fairly good viewing for anyone who wishes they were hanging out in a villa somewhere (though less good viewing for those isolating with friends they don’t trust). –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

My Brilliant Friend (HBO, 2018-present)

Based on: The Neapolitan novels, by Elena Ferrante

Streaming on: HBO GO

As previously reviewed: I can tell you: it is slow. But its slowness is part of what makes it great television. And for the record: I found all four actresses to be phenomenal, especially for being untrained, but also probably because of it. Gaia Girace, who plays teenage Lila, is particularly striking; it’s hard to look away from her when she’s on screen, which surely tracks with Ferrante’s vision.

The show, overall, is very loyal to its source material—it had to be, lest the fans revolt—and so let’s be real: the book is also slow. I don’t mean this as a criticism. My Brilliant Friend is slow, particularly at the beginning, because it is dealing with the minutiae of children’s lives. It has lots of characters whose names and ages and relationships to one another you keep forgetting. It is a thorough, detailed account of the consciousness of one girl living in relative poverty. Like Knausgaard’s My Struggle, with which Ferrante’s works are often paired as an example of “autofiction,” the slowness is part of the point. It’s what makes it feel like life. . . .

We’re not used to slow TV. We’re not used to slow anything anymore. And this show is so slow it has subtitles. I mean, when’s the last time you saw a television show with subtitles? I know: it’s hard to read a television show. That’s not what we come to television for. How are we supposed to also scroll through Twitter or our group text, because one screen is never enough, if we have to read the show we’re watching? Reading is for books! Well, yes. But you might want to bone up on your TV-reading skills. My Brilliant Friend is HBO’s first ever series to be shot in a language other than English—it was produced in conjunction with Italy’s RAI network—but it won’t be the last: they have an Israeli drama, filmed in Hebrew and Arabic, as well as a Spanish-language comedy in the pipeline.

For me, there is something deeply refreshing about the kind of attention the subtitles require from the viewer, a kind of attention not demanded by any other popular show on TV right now. You have to keep looking, even though there are a lot of long shots where no one says anything, and where in the book, you’d been hearing Elena’s thoughts. You also have to spend time being fully in the world of the neighborhood, lush in its bleakness, and of Ischia, lush in its lushness. You begin to notice things—facial tics, background space, the lighting. While watching, I thought often of Luca Guadagnino’s recent adaptation of André Aciman Call Me By Your Name. The adaptations faced a similar struggle—how to adapt a novel that relies heavily on the complex interiority of an outwardly quiet first-person narrator—and a similar solution: rely on silence, atmosphere, and acting. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Based on: Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, by Stephen King

Streaming on: Netflix

So Andy Dufresne gets sent to prison for the murder of his wife and her lover (“You strike me as a particularly icy and remorseless man, Mr. Dufresne.”) Her lover was a golf pro. And Andy did sit in his car looking at a gun, thinking about something (killing them? killing himself? we’ll never know) before throwing the gun into the river. So he’s sentenced to life, of course, and when they give you life, that’s exactly what they take, don’t you know. First night in Shawshank with the other “fresh fish” and BOOM, the sadistic guard Hadley beats to death some poor fat lad who won’t stop weeping. Red (Morgan Freeman), who has been in there for nearly 20 years at this point, bets on Andy to crack that first night. (“He looked like a stiff breeze would blow him over”) Andy doesn’t make a sound though. Oh, Andy is big into geology, polishing rocks, making them into chess pieces etc. Red is a man who knows how to get things, and so he gets Andy a rock hammer. Now warden Norton, he is one nasty piece of work. Big bible thumper, but also corrupt as all hell. “Put your trust in the lord. Your ass belongs to me.” Andy and Red become fast friends. But oh shit, now Andy has become the target of Boggs and his gang of rapists. Anyway, the rest of Red’s crew (nice fellas mostly) don’t really know what to make of Andy, don’t know how to reconcile his high breeding with the brutality of his crime. How does he endear himself to them you ask? Well, they’re all up on top of the prison one hot afternoon, tarring the roof, and Andy overhears Hadley nattering on about how he got some inheritance but the IRS are gonna take most of it etc etc and Andy, ballsy guy that he is, walks up to Hadley and says “Do you trust your wife?” and Hadley says “That’s funny. You’re gonna look funnier suckin’ my dick with no fuckin’ teeth,” which, as a line, in fairness. Anyway, Hadley gets pissed off at this line of questioning and tries to throw Andy off the roof, but just before he can Andy says “because if you do trust her there’s no reason you can’t keep all that money,” or some such. He agrees to do the paperwork required for a one time cash gift to your spouse (which is tax free, apparently. Or at least it was tax-free in 1940s Maine) in exchange for, wait for it, two beers a piece for every man tarring the roof. Red: “We sat there and drank with the sun on our backs and felt like free men. Hell, we could have been tarring the roof of one of our own homes.” Very nice moment. But let’s not forget about the raping, because that’s still going on. Until Hadley beats the bejesus out of Boggs. Red: “Two things never happened after that. The Sisters never bothered Andy again, and Boggs never walked again.” So what else what else… Oh, Andy starts writing to the prison board to get them sent books (Andy’s a big believer in reading and education). He writes letters every damn day until those books arrive and he builds a library. Oh, he calls it the Brooks Hatlen memorial library, or some such, because Brooks was an old inmate who had a pet crow (by the name of Jake I believe). Brooks got paroled but had been institutionalized, you see, and couldn’t keep pace with the world outside. So he hanged himself in the halfway house he was living in. Very sad. Andy also breaks in to the warden’s office at one point to play some lovely classical music across the PA system for the inmates. That earns in a spell in the hole, but I think we can all agree it was worth it. What else what else . . . –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Justified (FX, 2010-2015)

Based on: “Fire in the Hole” by Elmore Leonard

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Calling Justified, the FX series that premiered in March of 2010 and ran for six glorious seasons, a literary adaptation is at once misleading and fundamentally, somewhat poetically accurate. As a starting point, it’s nominally based on the Elmore Leonard short story, “Fire in the Hole,” which introduces US Marshal Raylan Givens, a plays-by-his-own-rules fugitive hunter who returns to his hometown of Harlan, Kentucky and has some tension with an old coal mining buddy turned criminal, Boyd Crowder. All of that gets the show through a few episodes. But what really, and a little counterintuitively, makes Justified such an achievement of literary adaptation is that even once the series was off-book, as it were, it always felt distinctly located within the strange and wonderful moral universe of Elmore Leonard’s fiction.

Every character had a hustle going, every crime required several minutes of banter, and the line between hero and lowlife was ever thin. The Crowders, the Crowes, the Bennetts, the Givens—all these hill clans, criminal or otherwise, carried down their own traditions and moral codes, and sure enough they more often than not came into conflict. Creator and showrunner Graham Yost has famously said that the writers of the series would wear bracelets bearing the initials WWED as a reminder, whenever they were stuck on a plot development or a character arc, to ask themselves, “What Would Elmore Do?” The great author’s stamp is all over this show, a modern western-cum-crime show that smuggles in a few Shakespearean touches and adds some pretty steamy sexual tension to boot. Through the magic of great source material and great week-to-week writing, not to mention the phenomenal acting, Justified established itself as one of the decade’s most entertaining series, and without a doubt one of its most stylish. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

There Will Be Blood (2007)

Based on: Oil! by Upton Sinclair

Streaming on: Netflix

Watch it with a homemade milkshake. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Winter’s Bone (2010)

Based on: Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone (which she also co-wrote with producer Rosellini) is a beautiful, gritty, horrifying masterpiece. Based on the novel by Daniel Woodrell and released in 2010, it is the story of a teenage girl named Ree (Jennifer Lawrence, before her rise to fame and giving the best performance of her career) who lives in the Ozark Mountains with her mother and younger siblings. She serves as the primary caretaker for her whole family—her drug-dealing father has disappeared, and her mother suffers from mental illness. When her family is threatened with eviction, she decides to track down her father. But the neighbors are resistant to her attempts to pry into her father’s life—and she is emphatically discourages by her uncle, a conflicted meth addict named Teardrop (John Hawkes) from searching any further. It is a brutal, cutting film—its pacing is incredibly suspenseful and the acting (often stony), is pitch-perfect. It is a movie of silence, of snow—muted sounds and colors. Until it isn’t, and it transforms into a shocking, scarring, and vibrant spectacle of horror. Debra Granik should direct every movie. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Blade Runner: The Final Cut (1982, 2007)

Based on: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick

Streaming on: Netflix

If you have two hours to spare, why not revisit the king of all SF movies, in all its glory, just as as God (er, Ridley Scott) intended? –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Sherlock (BBC, 2010-2017)

Based on: The Sherlock Holmes stories, by Arthur Conan Doyle (1887-1927)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventures of Sherlock Homes has taken on a life of its own. The characters have starred in other writers’ stories, and the premise has been adapted for television and film many, many times. The best adaptation, I daresay, features Benedict Cumberbatch as a brilliant, impatient, delightfully smug Sherlock to Martin Freeman’s compassionate Watson, an earnest war veteran who blogs about their crime-solving adventures. And who could forget Andrew Scott’s role as Moriarity? Before he was the Fleabag’s Hot Priest, he was a twisted mastermind pulling the strings in a theatre of cruelty. The crimes are eerie and psychologically haunting (years later, you’ll find yourself thinking of the woman in “A Study In Pink,” who tried to claw her daughter’s name in the floorboards before she died, as a clue) but there’s a playfulness there, too. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock and Andrew Scott’s Moriarity mirror each other in a clever cat-and-mouse dance, and it’s fun to watch. You buy into their love of the game. You learn to love it, too. (The fun makes it all the more creepy, really. You wonder if Sherlock, if all of us, aren’t a little more like Moriarity than we care to admit.) And, of course, the unlikely friendship between Sherlock and Martin Freeman’s Watson is another great joy of the series. The wonderful thing about this adaptation is that as it goes on, it becomes less about individual one-off mysteries and more about the characters’ backstories and growth, their individual psychology—the greatest mystery of all. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

The Social Network (2010)

Based on: The Accidental Billionaires by Ben Mezrich (2009)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: It’s not going to surprise anyone that David Fincher is has a prominent place on a list like this. His 2014 adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl claims one of the spots in the top 10. His 2011 The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo very easily could have made it, too—it was arguably one of the most anticipated adaptations in several decades, and despite a lukewarm critical reception at the time has been aging pretty well into something closer to wide acclaim. Mindhunter gets a nod in the TV department. But the real crowning achievement of Fincher’s impressive decade is the one with no killers, no gore, and no brooding violence at all, really, except the violence done to the American social fabric thanks to the rise of a new class of reckless tech billionaires. Somehow, with its dark campus landscapes, Trent Reznor score, and unabashed displays of ambition, The Social Network turns out to be one of Fincher’s most insidious, disturbing works. The adaptation, from Ben Mezrich’s 2009 book, The Accidental Billionaires, was done by none other than Aaron Sorkin, and like Mezrich’s book, the screenplay zeroes in on the lawsuits filed by the various founders and early developers of Facebook. Depositions have never been captured so perfectly on film, with Jesse Eisenberg as the seething anti-hero, Zuckerberg, facing off against rivals, enemies, and himself. Looking back almost ten years later, it’s incredible just how prescient The Social Network was about the principles and players behind social media. Fincher and Sorkin seemed to see clearly the insecurities and threats behind this strange force. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Hook (1991)

Based on: Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie

Streaming on: Netflix

Okay, so Hook is only based on Peter Pan in the barest of ways, but who cares? It’s a goddamn delight. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019)

Based on: A Song of Ice and Fire by George R. R. Martin

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Quibble with the final season, go ahead, I won’t stop you. Quibble with the bouts of misogyny and overly graphic/exploitative background action, which may or may not have been appropriate to the time and place depicted, a fantasy realm so who the hell knows? But what you can’t quibble with, or even overstate, really, is the cultural impact of Game of Thrones, one of the most fervently and widely watched series in the history of modern television and a global pop culture phenomenon like no other on this list. It didn’t matter if you were a fantasy nerd, a reader, an avid watcher of television, or a virtual recluse; chances are at some point during the decade past, Game of Thrones came across your radar, you decided to watch it, and probably got into some very involved discussions of its progress.

There were kings, queens, courtiers, schemers, risers, fallers, dragons, clashing civilizations, more dragons, and more worlds to discover every week. And it was ambitious to boot. With David Benioff and D.B. Weiss at the helm, adapting the epic works of George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire cycle, the priority was placed on closely observed worlds and the type of passionate, high-stakes storytelling that have marked sagas and origin stories from the dawn of time. Look, if you’ve read this far and have never tried or enjoyed Game of Thrones, I don’t know what to tell you. Probably you can’t be converted. Or maybe now that the dust has settled you’ll give it another shake. Maybe not. All I’m sure of is that for several years this decade, there was a show that a good portion of the human race was really, really into. It was the show everybody seemed to be watching, and when they went off-book, for better or worse, and drew the whole thing to a close, it was invigorating to know that a community around the world was fully immersed in the same rich story. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Watchmen (HBO, 2019)

Based on: Watchmen, by Alan Moore

Streaming on: HBO GO

Only a literary adaptation in the sense that it uses Moore’s characters, but one of the weirdest and best shows in recent memory. If you haven’t indulged, now is the time. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

High Fidelity (2020)

Based on: High Fidelity by Nick Hornby

Streaming on: Hulu

I’m pairing this with Watchmen because it’s also a creative use of IP—it’s more of an adaptation of the John Cusack move than it is of Hornby’s novel, but considering how close those are it doesn’t really matter. At any rate, it’s very fun, and filled with incredible music. It more than earns its place. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

True Grit (2010)

Based on: True Grit by Charles Portis (1968)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: True Grit, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen in 2010, is the second adaptation of Charles Portis’s 1968 novel of the same name. The first one, which was made in 1969 and starred John Wayne (in the November of his career), was a chipper, watered-down version of the original story, a vehicle for Wayne to pastiche his whole career as a crochety, no-nonsense cowboy. Wayne won an Oscar (kind of as a tribute) for his role as the crapulent, cantankerous, eye-patch-wearing U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn, forever associating himself and his legend with the film. The Coen Brothers’ retelling of the story fully (productively) ignores that the first True Grit even happened, drawing its script from Portis’s grim novel, to focus more on the protagonist that the first film dismissed: Mattie Ross, a formidable fourteen-year-old girl who arrives in a small town to retrieve the body of her murdered father. Played to poker-faced perfection by Hailee Steinfeld (and Elizabeth Marvel, later on), Mattie hires Rooster (Jeff Bridges, who has in the last two decades found his calling playing sloppy, insouciant older men) to hunt down and take into custody Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), her father’s murderer. Also along for the ride is a patronizing Texas Ranger named LeBoeuf (Matt Damon, who pronounces it “luh beef”). While the film is structured around the hunt for the killer, it is more about the relationships between the three characters on the journey—or, really, the lack of relationships between them. The film eschews the traditional “it’s the journey, not the destination” cliché of so many expedition-focused stories—the yearning for a connection between them is there, but they are not able to bring it to fruition.

But this is a Western, which means that the relationships that form are not limited to humans. Mattie’s most loving connection will be to Little Blackie, the shiny horse she picks out for herself to ride on the trip. He will (spoiler) ultimately give up his life to save hers, carrying her to medical care after an accident. Horses in True Grit, seem to play a particularly large role in the film’s construction of a moral hierarchy and are represented as providing integrity to an otherwise cold and chaotic world. As emblematized most obviously by the strutting, gauche Rooster, the wild west of True Grit turns everything and everyone into animals. As Mattie (her family’s breadwinner, now) tries to avenge her father, she is truly on the hunt for humanity and support—someone who can help her carry her family through this hard time. But humans, with their nominal superiority of morality and thought, will almost always fail her. And the film beautifully, sadly, darkly, watches humanity leave her with nothing—like the horses who love her back, she too must live as a beast of burden. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

A Single Man (2009)

Based on: A Single Man, by Christopher Isherwood

Streaming on: Netflix

Colin Firth is very, very good in Tom Ford’s adaptation of Isherwood’s classic—it has both style and substance, which is rarer than you might think. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Orange is the New Black (Netflix, 2013-2019)

Based on: Orange is the New Black by Piper Kerman (2010)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Admittedly, Orange is the New Black had its ups and downs (everyone has their own ranking, and while I’m not sure there’s any true consensus, I feel confident in saying Season 2 forever), but on the whole, it’s impossible not to highlight it here. We were introduced to the inmates of Litchfield Penitentiary in 2013, only a few years after the release of Kerman’s much-hyped memoir about her time as a Nice White Lady in prison, but the show has far eclipsed the book. Part of it was luck: it was one of Netflix’s earliest forays into original programming. As TV critic Judy Berman wrote:

Brought to bear on [creator Jenji Kohan’s] expansive vision at a critical moment in the rise of streaming, that freedom yielded a series that smoothed the transition from cable’s 2000s golden age to the vibrant and diverse, if fragmented, era that’s come to be known as Peak TV. More than a bold experiment in representational sleight of hand, Orange became the most influential show of the decade.

. . .

[I]t would be hard to underestimate how much has changed on the small screen since 2013. . . . the phrase “binge watching” was just starting to gain currency when the first season of Orange—all 13 hours of it—showed up on Netflix. Viewers who now regularly consume a full season’s worth of a given series within 24 hours still weren’t sure that they could get used to this new form of couch potato–dom. Kohan’s show played no small part in converting skeptics. I remember marathoning the season in a weekend, spurred on by my impatience to know everyone in Orange’s tremendous cast of characters. For better or worse, bingeing is now so common that a term for watching one episode of TV at a time would be more useful.

Which isn’t even to scratch the surface of what has really been so influential and satisfying about this show: its massive cast, and that cast’s ability to portray a diverse, complicated group of women—something never seen before on television, or at least not at this magnitude. Judy again:

When it came to representation, this wasn’t merely the first prestige show since The Wire built around poor and nonwhite people—or the rare program intended for a general audience that featured more than a token queer regular. It also endowed each of these characters with stereotype-defying specificity. In 2014, when this magazine declared that America had reached a “transgender tipping point,” Laverne Cox’s breakthrough role as trans inmate Sophia Burset made her the face of that moment. For once, women whom mainstream society habitually ignored were being represented in pop culture as individuals with virtues and flaws, rather than as a monolithic mass of degenerates or vixens.

And of course, it was a hell of a lot of fun, too. It had good stories, unforgettable characters, and witty repartee in spades—and those are probably why it’s actually been so massively popular: Netflix says that 105 million people (actually, users, which as we all know might mean multiple people) have watched at least one episode, which makes it the platform’s most-watched original offering. Which certainly says something. We’ll just forget about season six. And five. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Based on: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy by John le Carré (1974)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: Swedish purveyor of moody, broody atmospherics Tomas Alfredson (Let the Right One In) conjures the beige-hued, ashen-faced world of jaded British spycraft so impeccably in his adaptation of John Le Carré’s seminal 1974 novel that you can almost smell the stale cigarette smoke and flop sweat, feel the scratchy suit fabric and stained shag carpeting. Gary Oldman plays the latest incarnation of Le Carré’s beleaguered-but-deceptively-cunning career intelligence officer George Smiley, here brought out of retirement and tasked with rooting out a Soviet mole in the upper echelons of the secret service. Alongside him is a rogue’s gallery of stony-faced British acting royalty: Colin Firth, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch, John Hurt, and Tom Hardy, to name but a few. These are men whose emotional lives have been slowly eroded by the grim rituals and moral compromises of service. The whole thing is just so damn bleak, but in a transfixing kind of way. I know that’s a strange argument to make for exalting a film to Best of the Decade status, but Alfredson’s remake is such a fully realized vision that every time I sit down to watch TTSS (usually in the dead of night) I am instantly transported, mesmerized. It’s paradoxical, but there’s something both deeply soothing and deeply unnerving about following Oldman’s stoic, melancholy Smiley through the ruins of this fallen kingdom—a post-Kim Philby landscape of stagnating enmities and vanished idealism. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (2015)

Based on: Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke

Streaming on: Netflix

This transporting miniseries based on Clarke’s beloved alternate history is even better than you think it will be. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

The Leftovers (HBO, 2014-2017)

Based on: The Leftovers by Tom Perrotta (2011)

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Damon Lindelof and Tom Perotta’s supernatural mystery drama series (centered around brooding upstate New York police chief Kevin Garvey and his family as they struggle to adjust to life in the wake of the Departure—a mysterious global event that resulted in 2% of the world’s population disappearing from the face of the earth) was that rarest of birds: a literary adaptation that successfully expanded upon, and eventually transcended, its source material to become something altogether more glorious and profound. The first season (which many found too relentlessly grim but which I have a real soft spot for), a relatively straightforward adaptation of Perotta’s novel, focused on Garvey’s attempts to keep the peace between the still-raw citizenry of his small town and the inscrutable nihilist cult (the Guilty Remnant) which has ensnared his wife. The Second (which marked a complete tonal reimagining of the show) took place in Jarden, Texas—the site of the Garveys’ fresh start, chosen for its famed status as the only town in America which suffered no Departures—and the Third brought our battered antiheroes and their hefty emotional baggage to Australia as the auspicious seventh anniversary of the Departure approached.

There are so many scorching, aching performances in this show—from Christopher Eccleston’s increasingly desperate reverend to Ann Dowd’s uncompromising Guilty Remnant matriarch, Liv Tyler’s terrifying convert-turned-zealot to Scott Glenn’s grizzled and (possibly) insane Kevin Garvey Sr.—but none more memorable than Carrie Coon’s career-making turn as Nora Garvey, a woman stripped bare, reconstituted, by the enormity of her Departure Day trauma. Like Watchmen, Lindelof’s equally brilliant new creation, The Leftovers was a wildly ambitious vision—epic in scope, devastating in emotional impact, and admirably unafraid of drifting into silliness, surrealism, and near-incomprehensibility when it wanted to. It was a show about the weight of grief, about trying to live in a world made strange and terrible by incomprehensible loss, with all the rage and despair and absurdity that would characterize the experience of such a world. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

The Magicians (Syfy, 2015-2020)

Based on: The Magicians trilogy by Lev Grossman (2009-2014)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: I have a serious emotional problem which is that I love The Magicians and no one else does or knows what I’m even talking about. But this is not, as you might expect, because I love the books. I read the first book when it came out in 2009, pitched as “Harry Potter at grad school with sex and drugs,” and I remember enjoying it, but being underwhelmed. I am not underwhelmed by the show, which is hilarious, moving, and endlessly entertaining if you grew up reading fantasy. This may be the reason that not enough people watch or love this show: it rewards a lifetime of nerd-dom, and I see how it might be flatter without it.

For instance, one episode in the third season features a sequence in which two characters speak in code: the code being references from fantasy and science fiction. Another episode, in which two main characters spend their lives trying to solve a puzzle that could save the world, and die after many years spent together, is the most emotionally resonant thing I’ve seen on television in a long time.

Tonally, the show’s closest analogue is Buffy the Vampire Slayer—it starts off fun and quirky and self-effacing, the characters punning along as they beat the monsters-of-the-week—and winds up dark as all fuck. Plus, like Buffy, the transformations are everything. It’s worth watching this whole show just to see what happens to Margo. Don’t @ me until you’ve done so. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story (FX, 2016)

Based on: The Run of His Life: The People v. O. J. Simpson by Jeffrey Toobin (1997)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: For at least the past century, the United States has had a central role in enabling global celebrity cults thanks, in large part, to the Hollywood-industrial complex and the widespread diffusion of visual media. The appeal of memes and GIFs, as we now know them, have something to do with the spectacle of a re-playable moment, or a strange, indelible image circulated in like-minded groups. Ultimately The People v. O.J. Simpson, the first season of the American Crime Story anthology series, is a screenshot of one of the most pivotal cultural moments in late 20th-century U.S. history. This dramatization of the O.J. Simpson trial, steered along by an excellent cast led by Sterling Brown, Sarah Paulson, Courtney Vance, and Cuba Gooding Jr., took the audience back through a scandal seen around the world that revealed how wealth, fame, and race captivated the American public on the very eve of the Internet boom. What you didn’t talk about at the dinner table if you wanted to keep your most private feelings to yourself was money, religion, and whether you were for or against O.J. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

The Plot Against America (HBO, 2020)

Based on: The Plot Against America, by Philip Roth

Streaming on: HBO GO

As our reviewer put it: A Roth novel is preternaturally crammed with provocations and intuitions. The standard 90-120 minute film just can’t do justice to them. When it comes to adapting Roth, long-from television smites the major motion picture. With six hours at his disposal, Simon appears poised to break the curse. He has time, for example, to show us jarring montages of wartime footage, drawing out an underappreciated theme of the novel; namely, that news back then was often disseminated in movie theaters, houses of entertainment.

As for the look of the series, it is shot in a resplendent style—call it 1940s nostalgia vision. The interior scenes look like they were filmed through a camera lens slathered in honey. As for the characters themselves, Simon has interpreted them cleverly. Roth was well aware that southern Jews, uh, differed from their northern co-religionists. In the novel, traitorous Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf warmly invokes Judah Benjamin and the Confederacy. In the series, Simon outfits the rabbi (played by John Turturro) with a drawl so thick it makes Foghorn Leghorn sound like William Buckley Jr.

Friday Night Lights (NBC, 2006-2011)

Based on: Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream by H. G. Bissinger

Streaming on: Hulu

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: Many people’s choice for Best Show Ever, regardless of its literariness. And why not? It was a show about football that people who didn’t care about football would watch, a realistic but twisty story of a small town in America and its many connected inhabitants, and a deeply absorbing drama. It made you care. That’s about the best thing you can say about a show. There was just that one storyline that we don’t talk about. And neither does Landry. Just doesn’t come up again. It’s fine. We’ve forgotten it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Mindhunter (Netflix, 2017-present)

Based on: Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker (1995)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Though not quite true crime, the most fascinating characters and storylines of Mindhunter are based on real-life nightmares. Loosely inspired by Joe Penhall’s 1995 book Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit, the series is set in the late 1970s and early 80s, when the FBI first began systematizing the nature of “multiple murderers,” more commonly known as serial killers. Agent Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff), a brilliant and aloof hotshot in the bureau, teams up with the straight-shooting veteran agent Bill Tench (Holt McCallany) and psychologist Wendy Carr (Anna Torv) to do prison interviews with some of the most notorious mass murderers in US history to understand and apprehend active killers. This includes the likes of Ed Kemper, David Berkowitz (the “Son of Sam”), Charles Manson, and many more. The show leans into noir and, obviously, is not for those with a weak stomach or fluttering heart. Anchored by charismatic performances from the main cast and the excellent guest actors who play the criminals, Mindhunter makes you second-guess how much you can really know about the motivations and psychology of your neighbor, your relatives and, of course, yourself. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

The Handmaid’s Tale (Hulu, 2017-present)

Based on: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Disclaimer: The Handmaid’s Tale is on this list for the first season only. After that, it becomes misery porn. Despite the way its reputation has been corrupted by overextension and over-merchandising, the first season of The Handmaid’s Tale is incredible. The show is deeply affecting, especially coming at the time it did, when we were all feeling the first, dizzying moments of the normalization of Donald Trump’s behavior. Yes, we were tender, and this show drove the knife in. The adaptation is visually excellent, and extremely successful as horror. The third episode, in which a flashback shows the world just as the world tipped, made me cry, which is an uncommon event. At the time, I wrote:

The horror of the flashbacks is carefully balanced. This does not seem like a society at the edge of a dystopia. It seems exactly like the world we know. But it isn’t. Unless, of course, it is. Would we know? Moira and June laugh at the rude barista because they don’t realize where they live. They are standing on the edge; they can’t see how much things have changed. They are too close, and so are we. This is why the flashbacks are so much more frightening than the present action of the show, despite the bleakness and creep of the latter. A reflection of the violence of your own reality is always much scarier than any dystopian society with special outfits, no matter how many parallels you can draw, no matter how many people are tortured, murdered, or raped. I’m not saying these parts aren’t horrifying—just that they don’t cut to the bone in quite the same way.

That was the brilliance of Atwood’s novel, and that is the brilliance of the show—at least if we ignore everything after 2017. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Alias Grace (CBC/Netflix (2017)

Based on: Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

Streaming on: Netflix

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: A truly riveting adaptation of Atwood’s novel that was slightly undercut by the Atwood-glut we were going through at the time of its release. Sarah Gadon is hypnotic and unnerving; it was all over too soon. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Killing Eve (BBC, 2018-present)

Based on: The Codename Villanelle series by Luke Jennings (2014-2016)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: It seems like at this point we should probably have some kind of universal abbreviation to acknowledge how much we all love everything Phoebe Waller-Bridge does so that when the time comes to write about her, we can just pop it in there and not have to spend time trying to figure out a new way to talk about how great she is. For the purposes of this write-up, let’s just agree that everyone in the world would run our loved ones over with a truck just so Phoebe Waller-Bridge would… run us over with a truck. Killing Eve, Waller-Bridge’s adaptation of Luke Jennings’ Codename Villanelle and her follow-up to the first season of Fleabag, is a tremendously fun series that also manages to be taut with suspense. Jodie Comer is fantastic as the beautiful, charming, flirty asshole/contract killer whose mutual obsession with Sandra Oh’s British intelligence officer Eve powers the show, and Fiona Shaw is typically excellent as Eve’s boss/mentor/foil. The script is as sharp and fast and smart as anyone familiar with Waller-Bridge’s work would expect (seriously, run us over with a truck). –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

The Handmaiden (2016)

Based on: Fingersmith by Sarah Waters (2002)

Streaming on: Prime Video (I made an exception)

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: Park Chan-wook’s radical adaptation of Sarah Waters’s novel (by radical I mean he transmuted the action from Victorian-era Britain to 1930s colonial Korea, which was just as rigid and striated by class) was hands-down my favorite film of 2016, never mind my favorite adaptation of a novel. It starts slow, and quiet, which only makes what eventually unfurls—involving an elaborate, multi-faceted con, a torture chamber, a lesbian awakening, a library of porn, and an octopus—that much more striking. Every moment of this film, which is both a love story and a thriller, is gorgeous, and hypnotic, and sexy, and weird as hell. It is beyond good.

And though I know we’re not supposed to be considering the adaptation process, this one was remarkable: it improved upon a book that I already loved. As I wrote back in 2016, the film “excised everything I didn’t like about the book (an over-complicated, fairly slow third act, for one thing) and replaced it with what I really wished for—the collaboration between these two strange, powerful women. The experience of watching the film reminded me of reading contemporary retellings of fairy tales—it’s a deeply satisfying wish-fulfillment that takes something already good and vital and twists it until it’s unbearably delicious, until it’s exactly what you want. This felt like a feminist reimagining of an already feminist novel.” –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Lonesome Dove (CBS, 1989)

Based on: Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry

Streaming on: Hulu

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: The original Lonesome Dove miniseries is the best, picking up seven Emmys and becoming instantly iconic. In fact, according to The New York Times, it was so well done and popular upon its release that it “revitalized both the miniseries and Western genres, both of which had been considered dead for several years.” No sweat. Plus, um, Robert Duvall, Tommy Lee Jones, Anjelica Huston, Diane Lane, Danny Glover. I actually might be sweating a little now. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Harlots (Hulu, 2017-present)

Based on: The Covent Garden Ladies by Hallie Rubenhold (2005)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Harlots is the best show on TV you’re not watching—and possibly the best show on TV, period. Adapted from The Covent Garden Ladies: Pimp General Jack and the Extraordinary Story of Harris’ List, by Hallie Rubenhold, Harlots takes place in Georgian England, at a time when one in five women in London worked in the sex industry, and when many of the better paid escorts would receive reviews in a little black book that made its way to all the most discerning johns of the era, providing modern historians with rich details of a bygone era.

Harlots primarily explores the rivalry between two opposing bordellos; one is dedicated to providing basic shelter and protection for sex workers (for a small fee), while the other is classier, but more exploitative of its residents. Like The Deuce, Harlots provides a model for how to make a feminist show about sex workers. Harlots is not only based on a book by a woman, it’s also directed by a woman, stars primarily women, is written almost entirely by women, and generally passes the Bechdel Test in almost every scene. There was even (briefly) a blog created by sex workers to review each episode of Harlots.

It’s also incredibly well-written and oodles of fun, with more drama in each episode than in an entire season of Big Little Lies. Each season wraps up neatly but leaves plenty of room for the next, and as the show progresses, we’re introduced to the wider world of Georgian England, filled with bare-knuckle boxing, dissolute aristocrats, molly houses, and entrepreneurs of all stripes.

The lavish set design and deep historical research compliments the feminism of the series. Most sex scenes are filmed with sex workers fully clothed, given that it was far too cold and took too long anyway to take all those layers off. Heaving bosoms proliferate, as was the style of the era, but bright colors and warm lighting help distinguish the happier house of prostitution from the more miserable French-influenced house of procurement, where the women are clothed in pastels representing both the aspirations of their house and the rigidity of their madame. For every hooker with a heart of gold, there’s a complicated new take on an old archetype. Queer characters, and characters of color, make their own choices and live their own lives; gender and sexual identity are fluid, and kink alternates between sophisticated and played for laughs.

Hallie Rubenhold has dedicated her career to examining women’s choices (and women’s lots) within the context of their era—a valuable and eminently feminist project. She just won the Bailley Gifford Prize for her most recent work, The Five, which makes the case that Jack the Ripper’s victims were not employed as sex workers, but were, in fact, complicated 19th century women with complicated 19th century lives (primarily, the Ripper’s victims were unhoused women suffering from alcoholism). –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Dexter (2006-2013)

Based on: Darkly Dreaming Dexter, by Jeff Lindsay

Streaming on: Hulu

Look, it’s Dexter. Some of it is amazing, some of it is terrible. You already know this. It’s up to you whether you’re bored enough to dive back into all of it, but you should at least revisit season four. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Big Little Lies (HBO, 2017-present)

Based on: Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty (2014)

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: Big Little Lies is, on the whole, a good argument for letting Nicole Kidman and Reese Witherspoon do whatever they want; the show is a visually stunning meditation on the inner lives of its five leads, featuring the kinds of complex character studies we rarely see devoted to women. Based on Liane Moriarty’s novel, the show’s first season, directed by Jean-Marc Vallée, builds to a climactic reveal of the titular lie, and along the way it shows each of the five leads at the height of their acting abilities—particularly Nicole Kidman, whose portrayal of surviving physical abuse is unlike anything I’ve ever seen. The characters’ relationship to the surrounding landscape—the stark cliffs of Big Sur and the thin bridges that connect them, the ocean—underlie the show’s sense of tension and precarity, which we see expressed in the constantly shifting social alliances of white, wealthy, privileged Monterey.

However, the series is not without its flaws, and in particular, the show’s treatment of race has been disappointingly vague. The presence of Bonnie’s mother in the second season felt like a missed opportunity to introduce some nuance to that conversation; Reshmi Hebbar noted in Slate that her storyline “catered to racist stereotypes about violent black mothers,” exacerbating the show’s existing issues with race. And in the show’s second season, a battle for creative control between the show’s director and producers gave the show a visually muddled style. Regardless, it’s a pleasure to watch, and its strengths are enough to merit its place on this list. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Olive Kitteridge (HBO (2014)

Based on: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: Not many people watched this adaptation of Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel-in-stories, but the people who did know: it’s great. I mean, it’s Frances McDormand, so that’s really all you need to know. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

Based on: We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver (2003)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: What happens when someone you love turns out to be a monster? We Need to Talk About Kevin (WNTTAK) understands the complexities of love, grief, anger, and mourning intimately. Based on Lionel Shriver’s 2005 novel of the same name, the film has quickly surpassed its source material in both reach and reputation. Told from the perspective of Kevin’s mother, played to intense perfection by Tilda Swinton, WNTTAK begins with a lonesome Tilda, living in a rundown house and visiting her teenage son in prison. He’s done something terrible, something so terrible that Swinton’s neighbors no longer talk to her, but what? A gradual series of flashback sequences reveals Kevin’s difficult upbringing, his mother’s growing suspicion of his psychopathy, and finally, the explosive violence that lands him in prison in the first place.

If you prefer to end every film with the sensation that everything is pointless and we might just as well curl up in the fetal position and die (but also love exists and is very creepy), then this film is for you! It’s also part of a continuum of complex attitudes towards motherhood stretching back to Doris Lessing’s The Fifth Child and beyond. Motherhood is ambiguous. So is love. And so is that ending. . . –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Sex and the City (HBO, 1998-2004)

Based on: Sex and the City by Candace Bushnell

Streaming on: HBO GO

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: I’m actually not a huge fan of Sex and the City. I mostly missed it while it was on and it hasn’t aged particularly well, so watching through some of it recently didn’t exactly endear it to me. But I recognize that it is iconic and that a lot of people love it, and it has seven Emmys, eight Golden Globes, and three SAG awards, and hey, it’s based on a book of essays, and so here we are. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

If Beale Street Could Talk (2018)

Based on: If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin

Streaming on: Hulu

A bittersweet and beautiful film based on one of Baldwin’s lesser-known works. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

You (Lifetime, 2018-present)

Based on: You by Caroline Kepnes (2014)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: You is grim but also cheesy, and it is also just… great. It’s great. It is a variety of television maybe equivalent to a White Castle fast food order: highly addictive, bad for your blood pressure, fun to consume with friends, a little bit trashy but also highbrow (did you guys know that White Castle serves the Impossible Burger now?), and manufactured in Yorkville, a quiet neighborhood in Manhattan due East of the Upper East Side, home mostly to dog-owning elderly people, that bookstore where the show takes place, and the last white concrete hamburger palace left on the island.

Based on the novel by Caroline Kepnes, You is nostalgic for an old-school, local New York, which is clever because of the narrative’s heavy reliance on twenty-first-century digital technology. The show might seem to condemn social media, say, for being the reason why predatory men can find things out about the women over whom they obsess, but all the show’s roadsters, old books, and J.D. Salinger references remind us that what the show is, is old-fashioned. Actually, it’s timeless. Like the many beautiful brownstones and non-over-developed quaint neighborhoods the show likes to take us to, the creepiness and entitlement exhibited by You’s male protagonist have long been grandfathered into our culture.

The protagonist is Joe Goldberg (Penn Badgley), a mild-mannered bookstore manager and antique book restorer who falls for a young writer named Guinevere Beck (Elizabeth Lail). She prefers to be called “Beck,” which is dumb. Except then he stalks her—learning everything about her on the internet, watching her in her apartment, breaking into her apartment, stealing her things, murdering her good-for-nothing rich guy hookup, murdering her suspicious best friend, and eventually manipulating her into falling for him too, becoming her boyfriend while still continuing to stalk her. Mostly, he’s obsessed with taking care of her, and nurturing her talent (she is a mess). Actually, she is pretty poorly-written and I wish she were as good a character as Joe. She’s a very clichéd, lost-but-beautiful basic white girl with lots of privilege and daddy issues who is, we are told all the time, ‘a very good writer.” But she is, ultimately, a victim, and the most important thing about her character is that we know none of this is her fault. When she finds out what Joe is, she blames herself, and this is sad. Joe is responsible for it all. He is the spider and she is the fly. As she will write, in her best piece of writing in the show, he seems to be Prince Charming, but turns out to be Bluebeard. His castle will turn out to be her prison.

Joe is an extremely sinister figure, whose evilness is properly disguised and revealingly compounded by the fact that he thinks he is the protagonist in a romantic comedy, and that he is very handsome and charming. (The show sets a lot of scenes in that charming café from You’ve Got Mail on the Upper West Side, and you’re crazy if you don’t see parallels between Joe, and Annie in Sleepless in Seattle.) You has a few things to say about how many rom-coms (or fairy tales!) are actually creepy. The show is invested in representing how monsters are made of men, and this is sometimes very interesting and productive; other times, the show is fine to just thrill you with its shocking, suspenseful plot points. The intensity of Joe’s obsession (plus all scenes about graduate school) occasionally balloon into absurdity. Sometimes the writing is super sensationalistic. But it is also very serious and worry-inducing. You will worry about Beck. You will hope she gets away from him. You will worry about all women. And you will be scared by the idea that the cute guy you meet on a dating app might be a psychotic murderer. And then you’ll remember that Beck meets Joe in person, in a bookstore, and that the modern trappings of his villainy are purely incidental—a new framework for a very old, eternal danger. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Gossip Girl (The CW, 2007-2012)

Based on: the Gossip Girl series by Cecily von Ziegesar

Streaming on: Netflix

One of the 50 Greatest Literary TV Adaptations Ever: Let’s be frank: Gossip Girl is perfect. I mean that in the sense it does exactly what it sets out to do—whether or not you think it’s “good” on a moral or aesthetic level is kind of besides the point. It’s a rich-kid prep-school soap, and actually improves on the best-selling books. The early seasons are fun, taut, NYC catnip, and though (like many shows of its kind) it strains credulity and patience by the end, it’s iconic for a reason. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

The Haunting of Hill House (Netflix, 2018-present)

Based on: The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (1959)

Streaming on: Netflix

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary TV Adaptations of the Decade: The Haunting of Hill House, the book, profoundly moved me when I read it. (Haunted, actually, would be the term seeing as I couldn’t sleep for two weeks after completing it, but I’m trying to not be too on-the-nose.) Shirley Jackson published The Haunting of Hill House in 1959: Eleanor Vance a shy, anxious 32-year-old woman has just lost her mother, whom she had been nursing for 11 years, and has been invited by a paranormal researcher, along with two other people, to spend the summer at a haunted house. The possibility of escaping her drab life gives Eleanor the chutzpah to steal her sister’s car and, on her drive to the house, dream up an entirely new personality and life for herself. The Haunting of Hill House, the book, is focused entirely on Eleanor, her eccentricities, her anxieties, her relationship to the house which, creepily, gradually, reciprocates her attention in ways she did not anticipate. Jackson pried open the female psyche and criticized the oppressiveness of the household, the prison that could be the home, and in the process also wrote a hell of a ghost story. The Haunting of Hill House, the Netflix original series directed by Mike Flanagan, focuses on a family, the Crains, who live in Hill House until its hauntings become too much to bear.

One disturbing night, the father—having seen his wife increasingly grow ill under the influence of the house (seeing things, hearing things, being possessed: he wakes up one night to find his wife straddling in him in an attempt to kill him)—packs his five kids in the car and flees, leaving his wife to the cursed fate of the house. Flanagan’s show trades the feminist, subtle, horror of Jackson’s novel, for a more overt kind of terror, including jump scares and masked ghosts and women clinging to the ceiling even if he keeps some of Jackson’s original elements. Doors still slam unexpectedly, unexplained drafts plague certain parts of the house, and written on the walls in paint are the words, HELP ELEANOR COME HOME. All the same, the success and lingering impression of the series is its slowly unraveling family drama. A favorite, indelible episode is the most confrontational.

In “Two Storms” the family gathers for the funeral of one of its members and, as they all drink, they become as argumentative as they become sincere. The children ask their father for answers about the past, the house, his choice to abandon their mother, and finally, he tells them. The cinematography of the episode is stunning, placing its characters in the corners of one room of the funeral home, playing with shadows and deep colors and seamless switches between the characters’ perspectives. The narrative arc blends past and present, and their discussion is interspersed with flashbacks from 30 years ago. The episode is heartbreaking and tense and it is representative of the real pain and horror experienced by the family: the loss of their mother and their home and now, their sister and daughter. So, ultimately, coming to the Hill House series may not completely satiate those obsessed with Jackson’s masterpiece, but what Hill House offers is the untangling of fraught family relationships and so, it becomes, a study of vulnerability and connection, through the powerful lens of horror, that shows just how terrifying it can feel to love someone, unconditionally. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Lady Macbeth (2017)

Based on: Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District by Nikolai Leskov (1865)

Streaming on: Hulu

One of Lit Hub’s Best Literary Film Adaptations of the Decade: Has there ever been a protagonist more terrifying than Katherine, the Lady Macbeth of William Oldroyd’s haunting adaptation of Leskov’s novella (itself inspired by Shakespeare’s most famous female character)? Sure, a lot of characters are cold, and a lot of characters start with one little murder and then work their way up in intensity (of method and victim), but as I’ve written in this space before, most of them don’t, well, win at the end, and most of them aren’t played by Florence Pugh, who nails Katherine as a blank, amoral antiheroine in a fairy tale—one of the original fairy tales, where people routinely die, disappear and get dismembered—who suffers, more than anything else, from idle hands. It’s a shame more people didn’t see this film, despite its disturbing imagery; any lovers of Ottessa Moshfegh and Catherine Lacey and yes, the Bard himself, should seek it out. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.