Notable Literary Deaths in 2019

A Last Goodbye to the Writers, Editors, and Booksellers We Lost This Year

As if the year wasn’t bad enough, in 2019 we were obliged to say goodbye to far too many members of the worldwide literary community—from the universally beloved to the highly controversial, from the mega-famous to those who worked tirelessly behind the scenes. So before we break for the holiday, consider this a final farewell to some of the writers, editors, and booksellers we lost this year—though it is certain that for most, this tribute will not be their last.

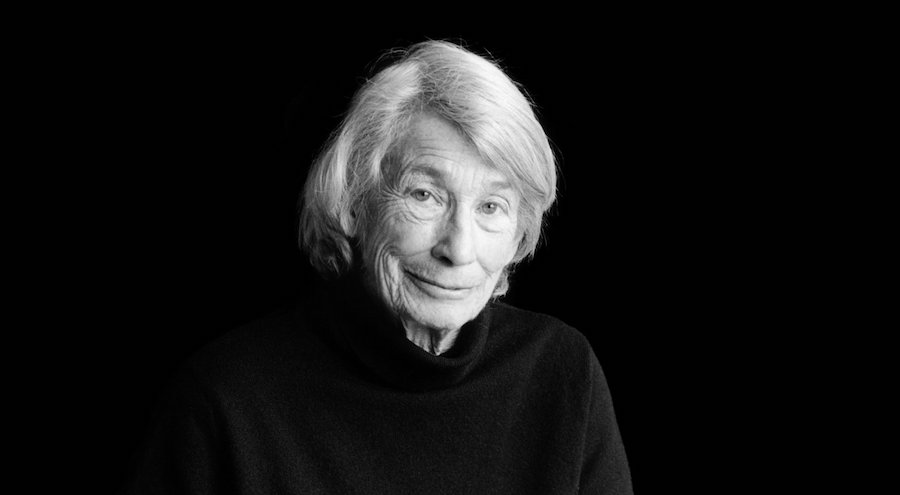

Mary Oliver, January 17

Prolific and widely loved poet Mary Oliver died early this year at the age of 83. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 for her collection American Primitive, and a National Book Award in 1992 for her New and Selected Poems. Known for her simple phrasing and her odes to the natural world—and also, if less so, for her eroticism—she was the rare kind of poet whose work sold, and it seems to have filtered down to just about everyone (i.e. not just habitual readers of poetry). Just before her death, Brandon Taylor wrote:

I first read Mary Oliver’s “Wild Geese” on Twitter, which explains something of why her work is both beloved and dismissed. It’s a boring discussion: I enjoyed this, but is it art? I won’t stoop to take the bait of it here. “Wild Geese” is one of those telegraphic poems that announces its meaning without flourish from the very outset: You do not have to be good.

It’s a poem of arresting lucidity and wisdom. It would be stupid to call it simple in that way that suggests that simplicity is a moral good or an aesthetically preferable state. But I also won’t say that it is complex, as though one needs to apologize for the spare nonpyrotechnics of the piece. Instead, I’ll say simply that “Wild Geese” is a poem that made me want to breathe again.

But as Margalit Fox put it in The New York Times: “Given its seeming contradiction—shallow and profound, uplifting and elegiac—Ms. Oliver’s verse is perhaps best read as poetic portmanteau, one that binds up both the primal joy and the primal melancholy of being alive.”

Susan Emshwiller

Susan Emshwiller

Carol Emshwiller, February 2

The decorated author of The Mount (2002) whom Ursula K. LeGuin once described as “a major fabulist, a marvelous magical realist, one of the strongest, most complex, most consistently feminist voices in fiction,” died in February at the age of 97. After her death, SFWA president Cat Rambo wrote that she was “one of the greats of short story writing, right up there with Grace Paley, James Tiptree Jr., Ursula K. Le Guin, and R.A. Lafferty, and she pushed its edges in order to do amazing, delightful, and illuminating things–just as she did with her longer work. As a short story lover, I am gutted by this loss to the writing community and plan to spend part of today re-reading Report to the Men’s Club and Other Stories, with its beautifully incisive and unflinching stories.” In 2005, she was awarded the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement.

Patricia Nell Warren, February 9

Patricia Nell Warren died in February at the age of 82; her celebrated second novel, The Frontrunner, was one of the first popular novels to feature an open gay relationship, and the first one to hit the New York Times bestseller list. “In contrast to earlier fiction about same-sex relationships, which tended to depict them as necessarily secretive, The Front Runner spoke to a younger generation by presenting the two men’s relationship in a forthright way,” Daniel E. Slotnik wrote in The New York Times. “Ms. Warren’s depictions of gay sex are explicit. The novel is also vivid in depicting the hardships and triumphs of running, all of which was grounded in her own experience.” It became a huge hit, selling some 11 million copies and becoming a touchstone for many young people discovering their sexualities; according to the Times the “book has been credited with inspiring the creation of more than 100 gay and lesbian amateur running clubs, now collectively known as the International Front Runners.”

Rachel Ingalls, March 6

The woefully underappreciated author of the absurdly good novella Mrs. Caliban, along with ten other books, died in March at the age of 78. Underappreciated, at least, until not long before her death, when New Directions reissued Mrs. Caliban. Better late than never—because as our own Dan Sheehan wrote,

Rachel Ingalls’ fictions are like nothing I’ve ever read before. To call her a practitioner of American Gothic doesn’t quite do justice to the blend of flavors she brings to the genre. Eerie hybrids of Richard Yates-esque domestic realism, B-movie horror, and surrealist fairytale, her stories and novellas subtly infuse quotidian life with a kind of hallucinatory menace, a pervasive sense of impending doom. To allow yourself to be led by her narration is to feel familiar spaces shimmer and degrade. By the time you piece the portents together, you’ve wandered into a nightmare. . . .

Certainly, anyone I know who has read Ingalls’ slim masterpiece, Mrs. Caliban—periodically rediscovered and acclaimed in the 36 years since its initial publication—has found it to be utterly transfixing. The story of a lonely, grieving suburban housewife and her passionate affair with a humanoid sea creature who has escaped from a government lab, Mrs. Caliban is an intoxicating mix of sensuality, sorrow, and supernatural horror, and a damn-near perfect novella.

Hard agree.

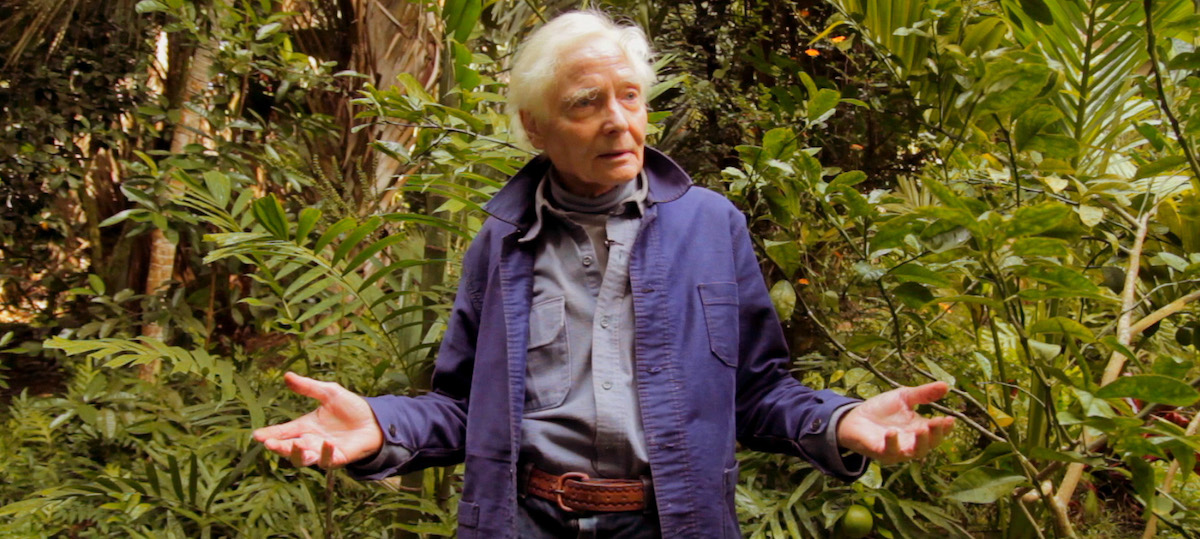

W. S. Merwin, March 15

Legendary poet W. S. Merwin died this year at the impressive age of 91. In The New York Times, Margalit Fox described Merwin as “a formidable American poet who for more than 60 years labored under a formidable poetic yoke: the imperative of using language—an inescapably concrete presence on the printed page—to conjure absence, silence and nothingness.” He was highly prolific, publishing poetry, prose, translations, and even a few plays, and highly decorated: he won two Pulitzer Prizes, one in 1971, one in 2009, a National Book Award in 2005, the Tanning prize, and a host of others. He was the United States poet laureate from 2010 to 2011. “Has there ever been a poet who has written in so many voices?” asked John Freeman.

The good, relentless student quality which has made Merwin such a great translator, and brought him early success, when applied to language over a lifetime gives us the sound of a poet who is perpetually preparing to meet his inspiration on its own terms, as if it is something he is merely guiding, not creating. As he writes in Rain in the Trees (1988), in the poem “Witness.” “I want to tell what the forests / were like,” it reads. “I will have to speak / in a forgotten language.”

Or take it from Edward Hirsch, who wrote that Merwin “is one of the greatest poets of our age. He is a rare spiritual presence in American life and letters (the Thoreau of our era).”

Vonda N. McIntyre, April 1

Nebula and Hugo Award-winning feminist SF author Vonda N. McIntyre, whose Dreamsnake is an under-read classic, died on April Fools’ Day at the age of 70. In addition to being a prolific writer, she was known as a mentor and teacher at the Clarion West writers’ workshop (alongside Ursula K. Le Guin and Octavia Butler, among others).

She was one of the women who made me think I could write science fiction,” Nisi Shawl told The New York Times. “She was instrumental in theorizing about birth control and sexual consent in the future, and she grounded her feminist concerns in scientific realities. That was amazing.” For the power geeks among you, she also wrote several Star Trek novels. (But the power geeks among you don’t need to be told that.)

Gene Wolfe, April 14

Gene Wolfe, “the Proust of Science Fiction,” and the author of the genre-topping series The Book of the New Sun, died this spring at the age of 87. “For decades people will say it’s strange that a book this visionary and bizarre was written by someone with Gene’s background,” wrote Brian Philips in The Ringer. “But what does that mean, since The Book of the New Sun is a work virtually without precedent? If Henri Bergson and St. Augustine had collaboratively edited a 1930s issue of Weird Tales, this is the text they might have produced. It’s strange that it was written by anyone. That it was written by the guy who figured out how to cook Pringles is no more startling than any other possibility.”

“Wolfe was a writer who occupied a unique niche by fusing together three seemingly divergent strands: pulp fiction, literary modernism, and Catholic theology,” wrote Jeet Heer in The New Republic. “His four-volume masterpiece The Book of the New Sun (of which The Shadow of the Torturer is the first tome) is an almost indescribable combination of speculative Christian eschatology with a Conan the Barbarian adventure story, written in a prose that can fairly be described as Proustian.”

Herman Wouk, May 17

Herman Wouk, the author of many historical novels, including his bestselling The Caine Mutiny, which sold three million copies in the US and won the Pulitzer Prize, died in May at the astounding age of 103—just 10 days before his 104th birthday, in fact. “His place in the literary universe was difficult to pinpoint,” wrote William Grimes in The New York Times. “Did he belong with the irredeemably middlebrow James Gould Cozzens and Thomas B. Costain, or popular but respectable writers like John P. Marquand and James Michener? His novels provided ammunition for both sides.” His work was frequently adapted to film and television (Humphrey Bogart played the lead in The Caine Mutiny) which probably didn’t help. Or hurt.

Binyavanga Wainaina, May 21

Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, winner of the 2002 Caine Prize for African Writing, founder of Kwani?, and one of Africa’s best-known writers and LGBTQ activists, died this year at the age of 48. “He was generous to a fault with so many artists, not only writers,” wrote Billy Kahora after his death. “He would champion someone’s work both artistically and practically in incredible ways. Nothing was impossible for a writer like him.” He was highly influential across continents, not least for his satirical 2005 essay “How to Write About Africa.”

“What does it mean when a writer like Binya dies but leaves his words behind?” Maaza Mengiste asked.

Provocative, dizzyingly brilliant, an advocate for LGBTQ rights, proudly African, proudly himself, so achingly and compellingly vulnerable. How do we mourn when his voice is so loud that it can still fill a room? . . . He has always outpaced himself, pushing language ahead in the process. What comes back to us is a testament to that continual struggle, also called invention. Also called flight. And now he is gone, unreachable, outpacing us again. What language is adequate to express this loss when he has invented his own and held ours up as ineffectual and often futile? Here he is: everywhere and nowhere, watching impatiently in another country of his own making, urging us onward, pushing us to match his pace. We will keep trying, Binya, in gratitude and in awe of a life so ferociously embraced and spectacularly lived. Thank you.

Judith Kerr, May 22

British children’s book author and illustrator Judith Kerr, who is most famous for her 1968 classic The Tiger Who Came to Tea, died in May at the age of 95. She also wrote semi-autobiographical children’s novels about a young Jewish girl fleeing the Nazis, which began with 1971’s When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit. “She was just so funny,” wrote Lauren Child after Kerr’s death. “Even last week she was joking with me on the phone about she was rather pleased that she was exactly the same weight she’d always been, but that she’d let it go a bit far . . . She could always make me laugh. She always seemed to see the good.”

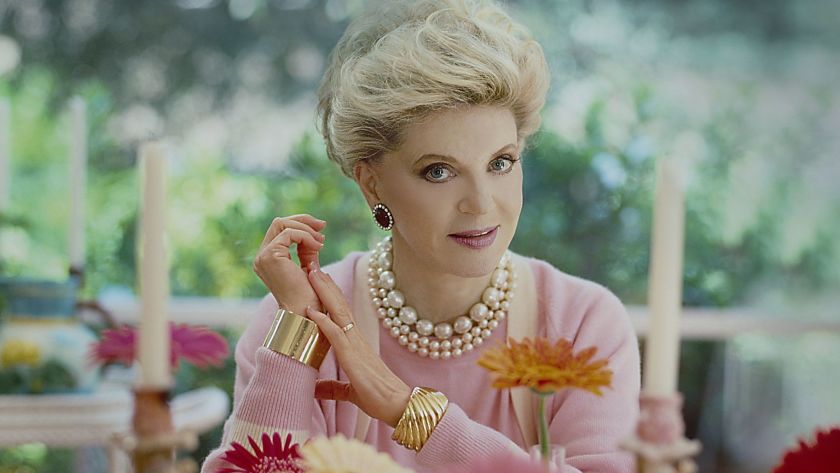

Judith Krantz, June 22

The mega-popular Judith Krantz—whose books have sold “more than 100 million copies in dozens of languages“—died in Bel Air at the age of 91. And by the way, that’s on the strength of only 10 books, the first of which Krantz published when she was 50. “What drove Ms. Krantz’s books to the tops of best seller lists time and again was a formula that she honed to glittering perfection: fevered horizontal activities combined with fevered vertical ones—the former taking place in sumptuously appointed bedrooms and five-star hotels, the latter anywhere with a cash register and astronomical price tags,” Margalit Fox wrote in The New York Times. “A hallmark of the formula was that it embraced sex and shopping in almost equal measure, with each recounted in modifier-laden detail. Elements of Ms. Krantz’s formula had existed piecemeal in earlier fiction for women . . . But Ms. Krantz was almost certainly the first writer to combine the steam and the shopping in such opulent profusion—and to do so all the way to the bank.” More power to her.

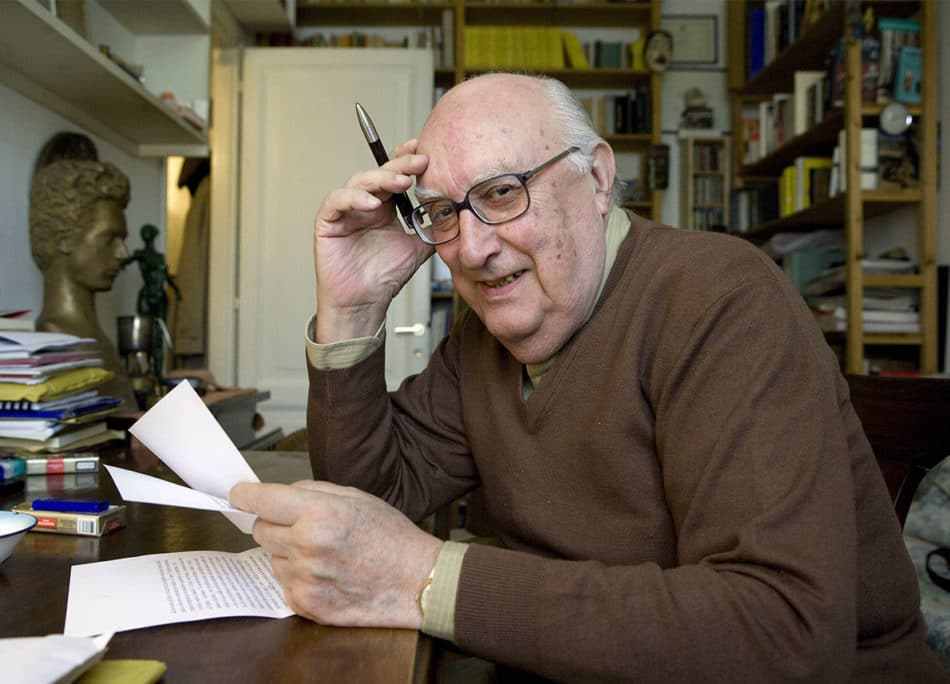

Andrea Camilleri, July 17

Andrea Camilleri, the author of the widely read and dearly beloved Inspector Montalbano novels (begun in 1994, when he was 69!), and one of Italy’s most popular authors, died this summer at the age of 93. “The Montalbano books are known not just for their distinctive inspector but also for a colorful array of underlings and other recurring characters,” Neil Genzlinger wrote in The New York Times. “And unlike most other crime series, they indulge in occasional commentary on Italian politics. Mr. Camilleri was not a fan of Silvio Berlusconi, the longtime prime minister, and his displeasure, which he voiced in a series of essays, could be detected in the books. ‘In my books,’ he told The Guardian in 2012, ‘I deliberately decided to smuggle into a detective novel a critical commentary on my times.'”

Jade Sharma, July 24

The author of Problems died in July at age thirty-nine. “Jade hated euphemisms and anything fake,” Ruth Curry wrote. “She would hate if I wrote “passed away” or “left this world.” If it were up to her, she would have written “fucking died.” She said what she thought, 100% of the time.” (That much is clear.) In the same remembrance, Dale Peck wrote:

Like all genuine artists who are also junkies, she screamed out for protection and indulgence in equal measure. As recompense for the fact that she was never going to get her act together, she offered up brilliant writing in exchange. Did it work? I feel shitty for even asking the question, but I also think it’s a question Jade wanted asked, mostly because she told me about a dozen times. And the sad, wonderful, unbearable truth is that Problems is a triumph. A triumph, and utterly heartbreaking.

They weren’t the only ones to think so.

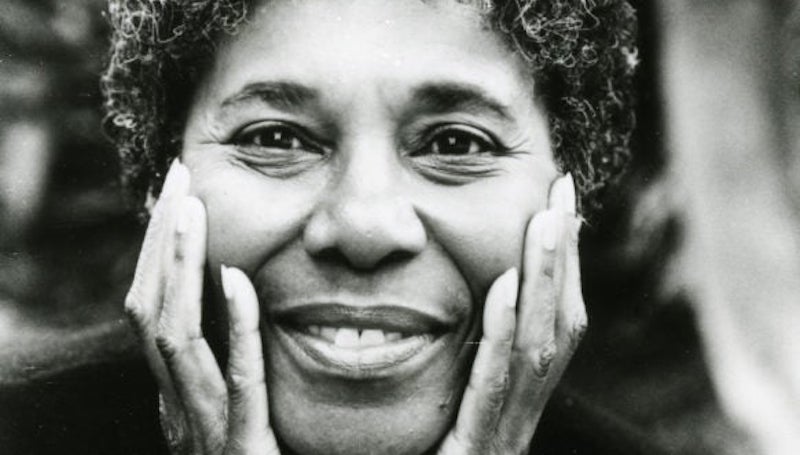

Toni Morrison, August 5

Despite the other luminaries on this list, I don’t think it would be controversial to call Morrison’s death, at the age of 88, the worst literary news of the year. The author of Beloved, Sula, and Song of Solomon was perhaps this country’s most important living writer, and certainly one of its best. In 1993, she was the first African-American to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 2012, President Barack Obama presented Morrison with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In a statement, Morrison’s family said: “It is with profound sadness we share that, following a short illness, our adored mother and grandmother, Toni Morrison, passed away peacefully last night surrounded by family and friends. She was an extremely devoted mother, grandmother, and aunt who reveled in being with her family and friends. The consummate writer who treasured the written word, whether her own, her students or others, she read voraciously and was most at home when writing. Although her passing represents a tremendous loss, we are grateful she had a long, well lived life.” The rest of us are grateful that she lived it.

Read bookseller Sheryl Cotleur’s letter upon the death of Toni Morrison.

Paule Marshall, August 12

Paule Marshall, the beloved author of Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), who was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant and the Dos Passos Prize for Literature, as well as a Lifetime Achievement award from the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards, died in Richmond at the age of 90. After her death, Rosamund S. King wrote:

Her description of Caribbean-American experiences in Brown Girl, Brownstones resonates with immigrants of many backgrounds in the midst of today’s vocal anti-immigrant sentiments. And her portrayal of everyday black women—those she called “kitchen table poets”—who seek lives of great joy and fulfillment, including both an intellectual life and sexual pleasure, provides a model for resisting seduction by the anger and despair that surrounds us. . . .

In her language and her content, Marshall was dedicated to the kitchen table poets— regular, every day, black Caribbean women who wanted big experiences in their lives: big love, big joy, big laughter. They looked around at their family and community members who were mostly content with just a little love, a little bit of wealth, and they decided to risk everything for more.

Charles Johnson also remembered Marshall in this space, writing:

I believe it’s safe to say that the zeitgeist of our time, especially during the Trump administration, is a period of polarizing ideologies. Because Marshall’s work represents a very high level of literary performance, it is not easily weaponized for social or political agendas. Its mission was always simultaneously humbler and grander than that. Namely, to offer us rich gifts from an educated imagination that, as John Gardner once put it, temper our experience, modify prejudice, and deepen a reader’s humanity. I do not know if there is a Paule Marshall Society at MLA or ALA. If not, I believe there should be one, and that her works should be taught widely in colleges and high schools for the literary standard she set for 65 years. We owe that to ourselves and generations to come.

Richard Booth, August 20

The self-proclaimed “King of Hay”—the king, that is, of the famous Welsh “town of books” properly known as Hay-on-Wye—died in August at the age of 80. As The Guardian explains:

Today Hay-on-Wye, a pretty but otherwise unremarkable border town, thrives thanks to the remarkable legacy of its self-appointed monarch, who helped to establish it as a centre for the secondhand book trade and to create the environment in which the annual Hay festival of literature and arts was founded in 1988. The narrow streets of the UK’s so-called Town of Books now buzz with tourists and incomers throughout the year.

Richard established his first bookshop in Hay, called The Old Fire Station, in 1962. With his gregarious manner and aristocratic bluster he succeeded in picking up for a song the household libraries of many landed families, and went on to set up half-a-dozen more bookshops in the town.

And yes, he did have a crown. And a cape.

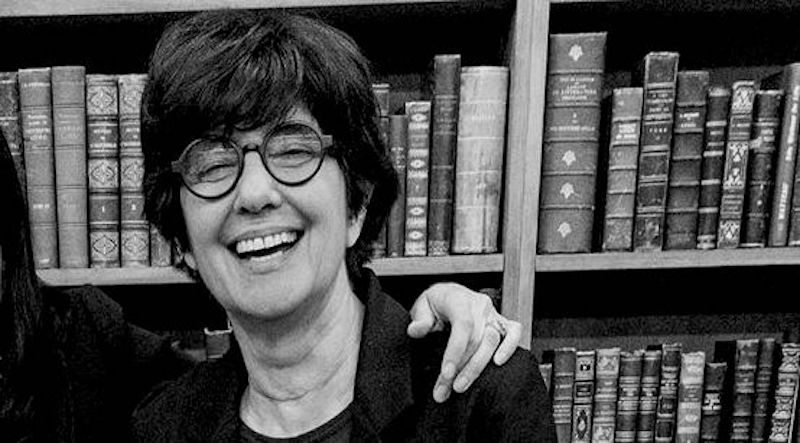

Susan Kamil, September 9

Executive vice president and publisher of Random House Susan Kamil, who published Salman Rushdie, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Elizabeth Strout, Sophie Kinsella, and Ruth Reich, and was widely admired by writers and readers alike, died in September at the age of 69.

Random House president Gina Centrello wrote to staff: “Her loss is shattering in so many ways. Susan was a brilliant editor, who guided her beloved authors through the creative process with the greatest insight, energy, and care. As a gifted publisher for the Random House lists, her leadership and generosity of spirit has had a profound and far-reaching impact. Above all, she was a deeply committed, endlessly supportive colleague to all of us—our unwavering, passionate champion.”

After Kamil’s death, our own John Freeman wrote:

Her trust in curiosity was so wild it seemed almost reckless. But it was a warm, patient and amused belief. Not in a million years would I call it mentor-like—she was simply decent. Kind. A fanatical supporter of the people behind her. And she made this way of being seem not at all at odds with her stylishness. Susan’s pantheon of writers was small and contained, but her manner suggested it was open to all to read and admire. I had never met an editor so willing to make what she did so transparent—who was so public with her love.

Decency. It’s such an unstylish virtue. It’s so often practiced behind the scenes. If it’s real, it’s also often spread so widely as to seem of little value—when in fact, in a world knit by relationships, being a spendthrift with it is the best proof of its authenticity. Susan was its cackling, kind, black-clad avatar.

We’ll need more of those.

Sol Stein, September 19

Legendary editor and publisher Stein not only published 13 books himself, but with his wife founded the publishing house Stein and Day, and served as its Editor in Chief for 27 years. While there, he published Elia Kazan’s debut (and bestselling) America, America as well as James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, which he edited. In fact he had a lifelong friendship with James Baldwin; according to the New York Times, Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. once described the friendship as “one of the great moments in interracial harmony and intimacy in the history of American literature.” He died at home at the age of 92.

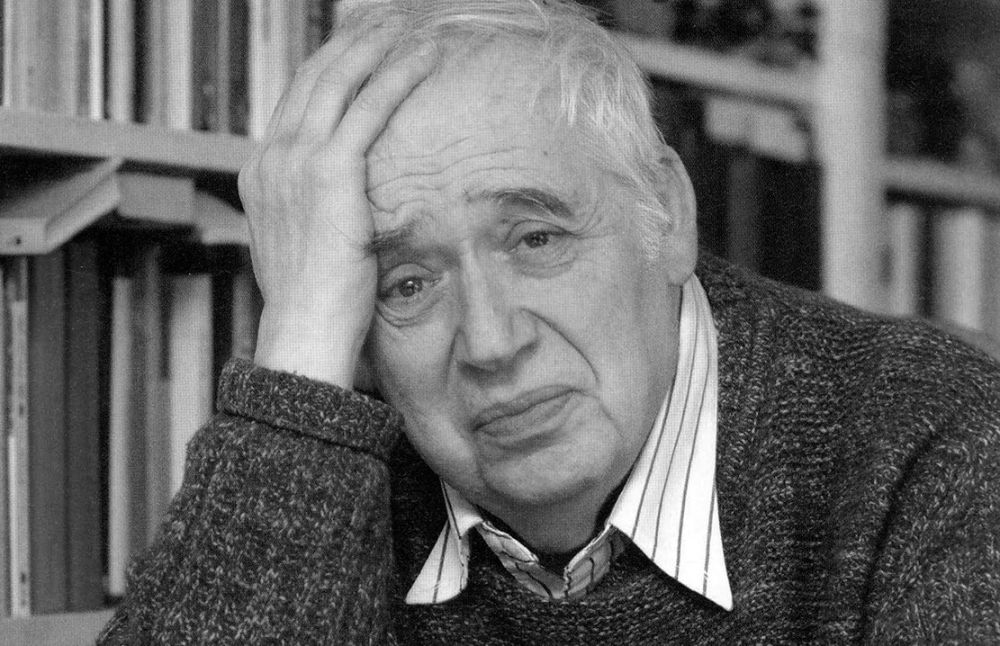

Harold Bloom, October 14

Literary critic Harold Bloom, who died in October at the age of 89, was a controversial figure to say the least. He was, as Dinitia Smith put it in the New York Times, “frequently called the most notorious literary critic in America.

From a vaunted perch at Yale, he flew in the face of almost every trend in the literary criticism of his day. Chiefly he argued for the literary superiority of the Western giants like Shakespeare, Chaucer and Kafka—all of them white and male, his own critics pointed out—over writers favored by what he called “the School of Resentment,” by which he meant multiculturalists, feminists, Marxists, neoconservatives and others whom he saw as betraying literature’s essential purpose.

It was also from this vaunted perch that Naomi Wolf writes he groped her as a student; Bloom has denied the accusation. But in this era, critical perception of both the man and his work is left decidedly mixed, though there is no denying his influence. “Take the Freudian “map of misreading” that Bloom drew and then lovingly embroidered over the decades,” James Wood wrote after Bloom’s death. “Like most good inventions, it is simple, easy to use, and above all, obviously true. This is why everyone still uses the term “anxiety of influence,” and knows what the phrase means, without having to have read a word of Bloom.”

Ernest J. Gaines, November 5

The author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971) and the acclaimed 1993 novel A Lesson Before Dying, which won the National Book Critics Circle award for fiction and was chosen for Oprah’s book club, died this year at the age of 86. Also in 1993, Gaines was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant; in 2000 he received the National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton, who said that “his body of work has taught us all that the human spirit cannot be contained within the boundaries of race or class”; in 2013 President Barack Obama presented Gaines with the National Medal of Arts.

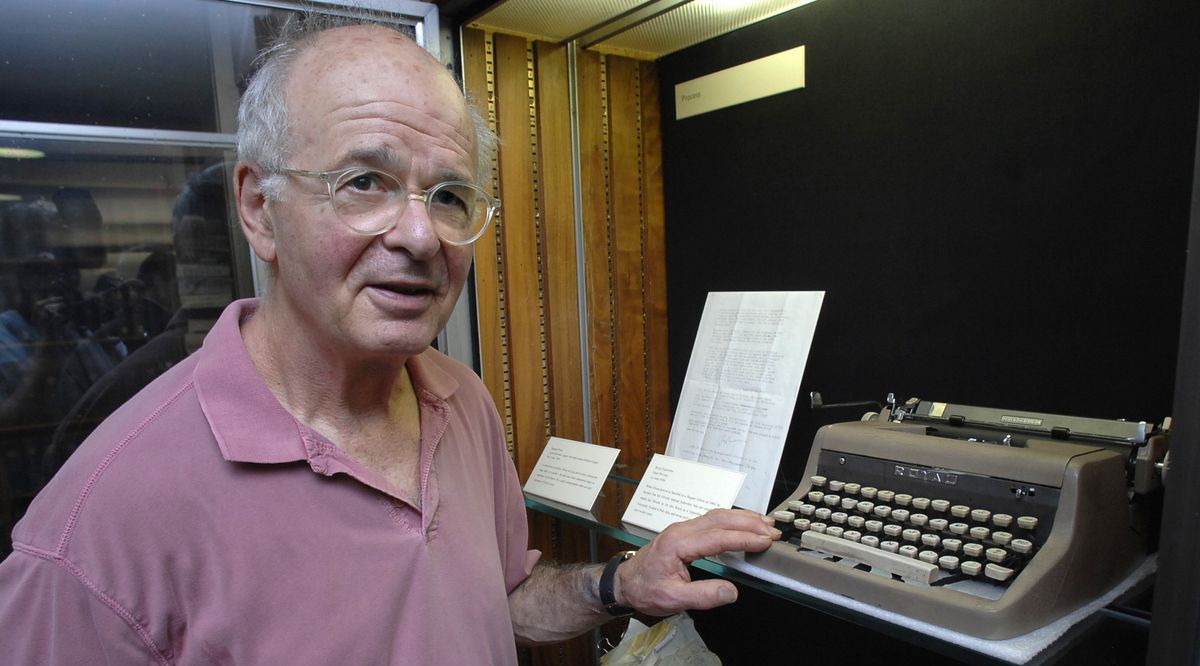

Stephen Dixon, November 6

Writer’s writer, experimentalist, and prolific weirdo Stephen Dixon, who was a two-time finalist for the National Book Award, died in November at the age of 83. After his death, his student, the novelist Kristopher Jansma, wrote:

He was a mystery. I read his novels at home, or tried to—some, like Gould (1997), I loved without quite understanding why. Subtitled “A Novel in Two Novels” the book was filled with dense, unending paragraphs and sentences that spanned pages. It was about a writer who seemed a lot like Stephen Dixon, only a lot less likable than the man we encountered each week at workshop. The book was dark and funny. It was what I’d learned to call “postmodern” and “experimental” but unlike much of what I’d seen in that vein at that age, his book was not dry or obtuse or academic. He’d unlocked a kind of secret, deeply personal space within all those enormous, intimidating paragraphs.

We all loved him. Loved the doodles he’d make in the corners of his responses to our work, which were always typed on a typewriter back in his office. Sometimes, he’d disappear after a break for ten or fifteen extra minutes, and we’d wonder if he’d forgotten us. We’d walk down the hall and listen at his door for the typebars hammering away. He was always in the middle of something, but he never left us for long.

Walter J. Minton, November 19

During his 23-year stint running G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Minton was the first American publisher to print Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, as well as Fanny Hill, and other novels that, as the Times put it, “rankled the guardians of decency but broke ground against censorship. . . .

But he was perhaps best known for books that challenged the nation’s prevailing notions and legal definitions of pornography. The most notorious of them had been banned in the United States and abroad and rejected by American publishers fearing prosecution for obscenity. They also faced a gantlet of decorous critics, clergymen and anti-smut crusaders.

He died at home at the age of 96. We thank him.

Robert K. Massie, December 2

The great Robert K. Massie popularized Russian history with his wonderful books, including Nicholas and Alexandra, which according to the Times “sold more than 4.5 million copies and is regarded as one of the most popular historical studies ever published,” and Peter the Great: His Life and World, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1981. He died in December at the age of 90.

*

Others we lost in 2019