Every Day is Earth Day: 365 Books to Start Your Climate Change Library

Part Four: The Ideas

The idea of a single day devoted to the earth is absurd. In the 49 years since the first Earth Day was celebrated, human civilization—checked by neither morality nor policy—has wrecked devastation upon the planet, increasing with each passing year of excess and inaction the likelihood that coming generations will live in a world unrecognizable to Senator Gaylord Nelson, who first conceived of the day as an environmental teach-in on April 22, 1970. But if there is any hope in righting this awful course, we need to think of every day as Earth Day.

With that in mind we have come up with the beginnings of a climate change library, 365 books that show us where we’ve come from, where we’re at now, how we might survive this crisis, and how we might cope if we don’t. With contributions from the likes of Richard Powers, Rebecca Solnit, Elizabeth Rush, Aminatta Forna, Maja Lunde, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Francesca Angiolillo, Stephen Sparks, Amy Brady, Jean-Baptiste del Amo, and many more, this collection is neither exhaustive nor fixed, and with the help of readers and writers alike, we hope to add to it in the coming months (and years, if we can). Divided broadly—and subjectively!—into four sections, we finish today with The Ideas, the philosophies, psychologies, politics, and pathologies arising from our proximity to environmental collapse. (Read part one, The Classics, part two, The Science, and part three The Novels and Poems.)

Featured art from Landscape Painting Now, edited by Todd Bradway, courtesy DAP.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

The gravest challenge to humanity’s existence is not climate change. It is our commitment to human exceptionalism and our belief that we make our own meaning—personal, exempt, and autonomous. No reductions in our carbon footprints, no miraculous increase in sequestration will save us, without our surrendering that commitment to purely private meaning. Our survival requires a revolution in seeing and being, one that is also a homecoming. We will not continue long on this Earth without becoming indigenous again, and that means remembering that human existence is wholly dependent on the lives of plants.

The tightly woven essays in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s radiant book are a call for that revolution and return to plant consciousness. Kimmerer is a bryologist and ecologist who teaches and conducts research at a major scientific institution. At the same time, she is a mother and an enrolled member of the Potawatomi Nation. Her attempts to braid together, through writing, those three ways of knowing the world lead her into an exploration of traditional ecological knowledge. As in the Native American planting practice known as Three Sisters, where the three natures of corn, beans, and squash provide reciprocal support and sustenance for one another, so Kimmerer’s lyrical and profound meditations join her own three natures—scientist, mother, and Native tradition-bearer—into a single braid. She teaches us that the term for plants in several Native languages translates as “those who take care of us.” Her words epitomize the recovery of a cast of mind that human survival will depend upon. We must unblind ourselves and learn how to see green things again. “Give thanks for what you have been given,” she urges. “Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken. Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

–Richard Powers

Elizabeth Kolbert, Field Notes from a Catastrophe

Kolbert is a seasoned journalist, and this book was one of the first to collate international studies about climate change. She provides a brief summary of the history of climate change research, then gives an overview of where and how climate change is being observed: melting permafrost, record melt on the Greenland Ice Sheet, changes in sea ice, shifts in ocean currents, the increasing number and intensity of hurricanes, etc. What’s interesting is comparing what was happening in climate policy and climate science in 2004-2005, while Kolbert was researching for this book, to today. The information and urgency around climate change were present even then, with then-Senator John McCain quoted as saying “This is clearly an issue that we will win over time because of the evidence.” Twelve years later, it doesn’t seem as though we’ve made much headway, and there are many people who still don’t believe that evidence.

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate

“There is still time to avoid catastrophic warming,” Klein writes, “but not within the rules of capitalism as they are currently constructed. Which is surely the best argument there has ever been for changing those rules.” Environmentalist and anti-capitalist at once, and like all of Klein’s work, incisive and brilliant.

Roy Scranton, We’re Doomed, Now What?

Roy Scranton, We’re Doomed, Now What?

Written by an Army veteran-cum-English professor, this provocative collection of essays sheds light on the systemic nature of war and climate change. The essays are well researched, beautifully written, and deeply felt. Moreover, they offer new frameworks for discussing and thinking about our very social structures—and how those structures reinforce the behaviors and beliefs we need to change most.

–Amy Brady

Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World

Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World

As humans, we’re typically stuck in our tiny human-sized conceptions of time. But in this book, Bjornerud asks us to think about time the way it’s experienced by the earth, our slow-moving giant of a home, giving us a biography of the planet on its own terms as well as an adjusted set of expectations for the future.

Michael E. Mann and Tom Toles, The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Change Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy

Michael E. Mann and Tom Toles, The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Change Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy

A cheeky, illustrated swipe at the nonsense of American discourse around climate change, complete with sections like “Science: How It Works,” and “Hypocrisy—Thy Name Is Climate Change Denial,” and “Geoengineering, or ‘What Could Possibly Go Wrong?'”

Charles Wohlforth, The Whale and the Supercomputer

Charles Wohlforth, The Whale and the Supercomputer

You think climate change feels scary from Miami or New York? It feels even scarier—and more real—on its northern front, in Alaska, where it has already radically changed daily life for its inhabitants. In this book, Wohlforth follows both scientists and Native Alaskans as they grapple with the massive effects of global warming.

Robert Bringhurst and Jan Zwicky, Learning to Die

Robert Bringhurst and Jan Zwicky, Learning to Die

For when nothing but philosophy will do: a slim volume that wonders how we should relate to the death of the planet, along with our own deaths, and how we should live when both are certain.

Mary Robinson, Climate Justice

Mary Robinson, Climate Justice

Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, explores climate activism at the grassroots level in Climate Justice. Her research takes her around the world, where she speaks with all kinds of people—a hair stylist, a farmer, a grandmother—who are mobilizing their communities to take action against climate change. Most of the people she profiles are women, and all of their stories are inspiring.

–Amy Brady

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement

Perhaps one of the best—and most controversial—academic treatises on how novelists are responding to climate change, The Great Derangement argues that climate change is almost too big, too unwieldy, and too downright strange to be rendered into familiar narrative forms. And yet, Ghosh argues, climate change should also be the focus of all great literature. Ghosh combines memoir, postcolonial theory, history, philosophy, science and other disciplines to support his arguments. Anyone interested in how writers are thinking about climate should pick up this book.

–Amy Brady

Donald Anderson, Below Freezing: Elegy for the Melting Planet

Donald Anderson, Below Freezing: Elegy for the Melting Planet

In this volume, Anderson takes an unconventional approach to climate change, assembling science, fiction, testimony, news reports, personal narrative and poetry in a kind of elegiac collage to our dying world.

Doug Bock Clark, The Last Whalers

Doug Bock Clark, The Last Whalers

Doug Bock Clark’s Last Whalers is a riveting account of an indigenous culture pinned between tradition and modernity. As with much in our current moment, a sense of loss permeates this deep journalistic foray into the lives of the Lamalerans, one of the last hunting and gathering cultures on earth, but Clark’s talent for capturing the full complexity of the people he writes about keeps the book afloat as it navigates the treacherous waters of the 21st century. This page-turning account of a culture on the verge of being capsized by the monoculture of global capitalism is an unexpected page-turning. I recommend it highly.

Roger Deakin, Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey through Britain

Roger Deakin, Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey through Britain

Waterlog describes Roger Deakin’s experiences of wild swimming in British waterways, inspired by John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer.” Deakin’s mission was to swim across Britain, from Cornwall to the east coast, by swimming through bays, rivers, canals, lakes, ponds, and one swimming pool. The book goes beyond swimming and looks at English history, woodland, rights of way and ancient hedgerows and advocates for open access to the countryside and waterways. Waterlog was the only book that Deakin published in his lifetime, but it was a bestseller in the UK and helped create the wild swimming movement.

Dahr Jamail, The End of Ice

Dahr Jamail, The End of Ice

A firsthand chronicle of onetime war reporter Jamail’s tour of the frontlines of the climate crisis, from Denali to the Great Barrier Reef, and a reminder of how magical the planet we’re about to lose really is.

Ken Ilgunas, Trespassing Across America

Ken Ilgunas, Trespassing Across America

An epic account of walking the route of the proposed, and for the moment quashed, Keystone Pipeline.

“The book is about my journey–fleeing from cows, taking cover from gunfire, and keeping warm on a very wintry and questionably-timed hike. But it’s also about coming to terms with climate change and figuring out what our role as individuals should be in confronting something so big and so out of our hands.”

Tim Dee, Landfill: Notes on Gull Watching and Trash Picking in the Anthropocene

Tim Dee, Landfill: Notes on Gull Watching and Trash Picking in the Anthropocene

Buffalo has Lake Erie and the Niagara River as well as mountainous landfills in the outlying areas: Gulls are no strangers here. However, Landfill both astonished and surprised me. Initially addressing the anthropocentric nature of gulls and human waste disposal, it becomes much more than the subtitle promises. Dee writes like a charismatic literature professor lecturing in front of a room of environmentalists and birders auditing a class. Culling from the works of Beckett, Borges, Chekhov, Larkin, and so many others, he explains and illuminates both purposeful and forced adaptation. There is much to be learned about planetary destruction from studying birds.

Barry Lopez, Horizon

Barry Lopez, Horizon

I think in the future two human habits will baffle those who occupy earth after us: what we eat, as in how much meat and how we factory farmed it; and how we traveled. As in how little we thought of journeying thousands of miles across the globe for small purposes. Major breakthroughs must happen in both aspects of 21st century life if we’re still going to have a future, so a book like Horizon–Barry Lopez’s thirty years in the making autobiography–has many layers of mourning built into it. This is, without a doubt, a traveler’s memoir, a West with the Night of a North American seeker. From Australia to Japan, to parts of Africa and the remote Arctic, this book follows the contrails of memory back to journeys Lopez took and describes what he saw and why he went. In this way, Horizon is also a chilling but somehow comforting psalm for the anthropocene: time and again he intersects with animal life, and their mysterious and numerous ways of knowing. Tries to divine them, or at least pay tribute on the hope that some day maybe we will. It turns out we need a horizon of human knowledge just as much as we need a record of who and what was here: beautifully, elegantly, this book manages to provide us with both things.

-John Freeman

Lauret E. Savoy, Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape

Lauret E. Savoy, Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape

Lauret Savoy is an environmental studies and geology professor whose work often searches for the overlap of personal, national and natural histories. Savoy is a woman of mixed heritage, and in Trace she goes back in time to follow the circuitous paths her ancestors took to reach her—all the while documenting the ways in which these European colonists, African slaves, and indigenous Americans impacted the earth.

–Aaron Robertson

Lauret E. Savoy, Alison H. Deming, The Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity and the Natural World

Lauret E. Savoy, Alison H. Deming, The Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity and the Natural World

Savoy also teamed up with science writer Alison H. Deming to co-edit a collection with similar ambitions, The Colors of Nature, which features contributions from authors like Jamaica Kincaid, bell hooks, Yusef Komunyakaa and others writing on everything from the toxicity of national myths to the “language” of the natural world. It is a volume that demands both ecological and cultural awareness.

–Aaron Robertson

Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World

In this provocative book, science writer Emma Marris explores conservation—of spaces and species—in the context of climate change. She argues that no place in the world is “pristine” because climate change has affected even the backcountry regions of our favorite national parks. The notion of a “pristine” wilderness is a bit of a red herring, as conservationists more often speak of nature as being wild rather than pristine. Marris discusses an example from British Columbia, where foresters are re-planting clearcuts with seedlings that are expected to survive in the biogeoclimatic ecosystem (BEC) zone those regions will turn into in the future—a process called “assisted migration.”

Marris also suggests we embrace exotic/invasive species that appear in our area because of climate change, and that we support “novel ecosystems” (those altered by human activity but not actively managed), particularly if they are interacting as a complex ecosystem and providing key ecosystem services. She also advocates for accepting green or wild spaces in urban areas as functioning ecosystems. This perspective in particular has taken off in the past five years, with an increasing number of scientists studying urban ecology. Marris writes, “I think we should keep lots of land unmanaged just to see what it does, to keep those evolutionary fires burning, and to ensure that future generations might still be able to get lost.”

Kathleen Dean Moore, Great Tide Rising: Toward Clarity and Moral Courage in a Time of Planetary Change

It’s one thing to understand the science behind climate change, sea level rise, freshwater challenges, species extinctions, and conservation of biotic systems. It’s another thing to consider our moral responsibility to maintaining these processes, instead of mortgaging our children’s future for our own comfort in the present. Moore, a Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Oregon State University, taps into her own experiences at both her Alaska cabin and her Oregon home to outline a moral and ethical approach to our responsibilities re: climate change. Moore argues that: “climate change is a violation of human rights . . . a crisis of the imagination . . . [and] a crisis of character.” She outlines “reasons for saving the world,” and notes that she and a group of 23 colleagues drafted The Blue River Declaration, which starts with: “A truly adaptive civilization will align its ethics with the ways of the Earth.” One thing that stands out about this Declaration—and the book itself—is how many people it will really reach. Who even knows about the Declaration? Who is thinking about the moral issues around climate change? While Moore skillfully weaves personal experience with philosophical approaches to sustainable living on planet Earth, I suspect her audience is limited to the privileged few, and will likely not reach the marginalized people most affected by climate change.

Thich Nhat Hanh, Love Letter to the Earth

Thich Nhat Hanh, Love Letter to the Earth

We could do a lot worse than Thich Nhat Hanh as our global moral leader. Here, he makes a very Buddhist argument for the interconnectedness of humanity with the earth—one is simply not possible without the other, and in fact both are the same, and if we love ourselves (and, not for nothing, want to survive) we need to love the planet in the same way.

James Garvey, The Ethics of Climate Change

James Garvey, The Ethics of Climate Change

A primer on ecological ethics. Should be required reading for… everyone?

Mark Lynas, High Tide

Mark Lynas, High Tide

An early climate change classic. “President Bush and his Administration have risen to the global warming challenge with responses ranging from obfuscation to pretense to outright denial,” Lynas writes in the preface. “I’d like to issue each and every one of them a challenge. Come with me—see what I have seen—and try to understand what global warming really means for us and for our children.”

Wendell Berry, Our Only World

Wendell Berry, Our Only World

These ten powerful essays by America’s leading agrarian philosopher are among the most thoughtful writing available in the US on stewardship of our environment. Stern, sometimes grumpy, always independent, Berry is at his best when the gap between idea and practice is as small as can be. Passionately, he argues we need to make this gap almost invisible when it comes to the planet. We need to think of values and activities, Berry says, which are intolerant of abstracting. Is it crazy to think of love, when we think of our planets forests? “To say that the good care of the forest, as of all the world’s places, depends upon love is, sure enough, to define a difficulty. But not an impossibility. The impossibility is that humans would ever take good care of anything they don’t love.”

–John Freeman

William T. Vollmann, No Immediate Danger

William T. Vollmann, No Immediate Danger

At the beginning of Vollman’s twelve hundred page, two volume Carbon Ideologies, once described as “the Infinite Jest of climate books,” he writes: “I do my best to look as will the future upon the world in which I lived—namely, as surely, safely vanished. Nothing can be done to save it; therefore, nothing need be done. Hence this little book scrapes by without offering solutions. There were none; we had none.” It’s not a manifesto, but a massive deep dive into manufacturing, the economy, fossil fuel extraction, nuclear reactors, and everything else contributing to the “hot dark world” we will soon inhabit.

William T. Vollmann, No Good Alternative

William T. Vollmann, No Good Alternative

Volume two of the account of the end of our world. Vollman will still be writing these even after the world is over.

Edward O. Wilson, Half Earth

Edward O. Wilson, Half Earth

In the final volume of naturalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Wilson’s trilogy, he makes a case for a plan to save the planet: set aside 50 percent of it as human-free zones. This would stabilize the environment and save everyone who lives on earth, he argues—including, of course, us.

Fred Pearce, The New Wild

Fred Pearce, The New Wild

Change is a constant reality, Pearce argues in this 2015 book, and almost no part of nature is still “pristine.” In fact “we need to lose our fear of the alien and the novel” and change with our environment.

Leslie Marmon Silko, The Turquoise Ledge

Leslie Marmon Silko, The Turquoise Ledge

Drawing on a rich family history that includes the Laguna Pueblo and Cherokee, and Mexican and European ancestry, Silko takes us to the heart of the Sonoran Desert near her home in Tucson, where she’s lived for over 30 years: “Just before the sun rises over the mountains . . . a breeze stirs and there is a silence as it might have been 500 or 1,000 years ago . . . here the desert is as it always was.” Silko is a master at cohabiting with nature: she shares her yard and the crawl space under her house with several species of rattlesnake. She makes food for wild bees and hummingbirds, and watches gorgeous, magenta-tinged grasshoppers feed on her flowers.

But her connection to landscape is also spiritual. To Silko, the land comes alive through the Laguna stories told to her by her grandmother and other family members: “The ancient ones are nearby. Sometimes late at night in the wind you can hear them sing or on a long hot summer afternoon you can hear them laughing and talking in the shade.” Her daily walks through the local arroyos are focused on finding turquoise, which is associated with legends that bring desert rain: “ . . . Turquoise Man [travels] with the rain . . . he calls for the rain so the runoff water come to the arroyos.” The landscape is Silko’s guide, showing her what she needs to see and learn.

–Sarah Boon Roy Scranton, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization

Roy Scranton, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization

When Scranton arrived home to America from his Army tour in Iraq, he was confronted with problems even bigger than Al Qaeda: hurricanes, rising seas, disease outbreaks, and other catastrophes resulting from climate change. Scranton combines memoir, reportage, history, science, and literary analysis to explore what it means to be alive today—and what it might mean in the future. Provocative, erudite, and wonderfully lucid, Learning to Die might be one of the most important books of the Anthropocene.

–Amy Brady

Gleb Raygorodetsky, The Archipelago of Hope: Wisdom and Resilience from the Edge of Climate Change

Gleb Raygorodetsky, The Archipelago of Hope: Wisdom and Resilience from the Edge of Climate Change

Too often in conversations about climate change the voices of Indigenous people are absent. Raygorodetsky, a conservation biologist who’s spent more than two decades working with Indigenous communities, seeks to change that with The Archipelago of Hope. Through first-person accounts and passages that allow Indigenous people to tell their stories in their own words, this book explains how Indigenous ways of life contribute to biological diversity and conservation.

–Amy Brady

Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, Nils Bubandt (eds.), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet

Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, Nils Bubandt (eds.), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet

This immensely readable—if somewhat academic—collection features essays by experts in anthropology, ecology, science studies, art, literature, and other fields. Organized around two metaphorical figures, “ghosts” and “monsters,” the collection touches on a wide range of subjects that inspire new ways, or “arts” of living, including the social organizations of different animal species and indigenous perspectives that view all life on earth as interconnected.

–Amy Brady

Dr. Qing Li, Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness

Dr. Qing Li, Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness

I received this book a bit ago and had let its place in the pile steadily get closer to the floor. In the meantime I read Richard Powers’ The Overstory and was fully devastated. And then an ah-ha moment: I searched my pile for Forest Bathing knowing it would serve as antidote to the mind-blowing wreckage realized in Powers’ book. It helped. I have always leaned on trees when feeling ill or confused, trekked into the forest and sat, hands sifting through the forest floor. Look to the forest for salvation, Forest Bathing instructs. Ease worries, get healthy, allow for connection to the natural world as you go deeper into the realm where living things are thousands of years old, wear the scars of survival, and serve as host to magical possibilities of healing. To know that Shinrin-yoku (Forest Bathing) is an official practice growing in popularity around the world helps me to believe that humankind hasn’t appropriated the natural world only to fuck it up. FYI : It will help to believe another outcome is possible if you use this Ursula Le Guin book title as mantra: The Word For World Is Forest.

Jonathan Franzen, The End of the End of the Earth

Jonathan Franzen, The End of the End of the Earth

Love him or hate him, Jonathan Franzen remains a master wordsmith, especially when writing about the environment. That talent is on impressive display in his latest, The End of the End of the Earth, a collection of speeches and essays written the past five years about environmental and other politically tinged topics. Some are also self-examining. In the opener, for example, he questions whether his beef with the Audubon Society was worth the public blow back. Other pieces unpack his complicated relationships with family. Taken together, these writings present a nuanced and provocative look at the world and the author himself. An avid fan, I’ve read everything by America’s favorite literary curmudgeon, and to my mind, this is his best collection to date.

–Amy Brady

Nicole Walker, Sustainability: A Love Story

Nicole Walker, Sustainability: A Love Story

Walker’s smart, funny, and practical book about how to live sustainably is perfect for the burnt-out environmentalist. It addresses head on the hypocrisy of living in the modern world, acknowledging that it’s almost impossible not to contribute to climate change and ecological destruction with every choice we make. This is the perfect book for bacon-loving, car-driving, but well-meaning people who also want to make a difference.

–Amy Brady

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

Written by the celebrated eco-feminist scholar Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble draws from the annals of weird fiction and sci-fi to build a new framework for thinking about life on earth during climate change. Haraway argues that “Anthropocene” is no longer an apt name for our era. Instead, she says, it should be called the “Chthulucene,” because we should all be thinking about how our human lives are intricately linked—like tentacles—to other, non-human lives.

–Amy Brady

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

Timothy Morton is one of today’s leading philosophers on climate change. With Hyperobjects, he argues that some phenomena—like climate change—are too big and all-encompassing for humans to fully understand. He calls these phenomena “hyperobjects,” and goes on to explain how their existence impacts the very ways in which we think and live.

–Amy Brady

Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence

Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence

With Dark Ecology, the renowned eco-philosopher Timothy Morton explores humanity’s historical relationship with nature to show that we’ve developed some “dangerous” ideas over time about the natural world. He also introduces important and helpful ways of thinking about our relationship to nature, such as the “feedback loop,” so that we can be more conscious of how we interact with non-human lifeforms.

–Amy Brady

Patrick Nunn, The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World

Patrick Nunn, The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World

In which Nunn finds that ancient folktales from nonliterate cultures have valuable information about massive climate changes—a surprising, perceptive take on how (and why) we know what we know—and how we could know more.

Jordan Fisher Smith, Nature Noir

Jordan Fisher Smith, Nature Noir

Nature Noir, true to its great title, reads like the best straight-up crime fiction, but it’s actually a memoir of Jordan’s time as a law enforcement officer in the “accidental wilderness” of California’s American River canyons. Slated to be drowned underneath the planned Auburn Reservoir, the canyons attracted misfits and miscreants like a magnet collects iron filings, and Jordan and his fellow rangers were called upon to manage a Mad Max atmosphere in which everyone seemed to be armed, drunk, or both. Author Jordan came away with a profound understanding of the social, environmental, and poetic implications of what he’d seen, which he reports in a gripping, intelligent book.

Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations

Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations

A new collection of essays from New York Times opinion writer Margaret Renkl, in which her young life in Alabama and the natural world around her combine to bring a new understanding of self and place.

Ellen Meloy, Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild

Ellen Meloy, Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild

A book about communing with bighorn sheep that is also about humanity’s dissolving relationship with nature and the other creatures on the planet, filled with fascinating observations, beautiful imagery, and advice on how to reconnect with the world around us.

Peter Singer, One World Now: The Ethics of Globalization

Peter Singer, One World Now: The Ethics of Globalization

A recent update on Singer’s classic text, which evaluates everything from climate change to foreign aid to immigration to economic globalization from an ethical standpoint. Turns out you can’t actually fix the whole planet without talking to other countries—who knew?

J. Drew Lanham, The Home Place

J. Drew Lanham, The Home Place

“In me, there is the red of miry clay, the brown of spring floods, the gold of ripening tobacco,” writes ornithologist and wildlife ecologist Lanham. “I am, in the deepest sense, colored.” This memoir, he writes, is “the story of an ecosystem,” and it unravels the intersections between environment and race, our physical landscape and our cultural one. “More and more I also think about how other black and brown folks think about land,” he writes.

I wonder how our lives would change for the better if the ties to place weren’t broken by bad memories, misinformation, and ignorance. I think about schoolchildren playing in safe, clean, green spaces, where the water and air flow clear and the birdsong sounds sweet. More and more I think of land not just in remote, desolate wilderness but in inner-city parks and suburban backyards and community gardens. I think of land and all it brings in my life. I think of land and hope that others are thinking about it, too.

Christopher Potter, The Earth Gazers: On Seeing Ourselves

Christopher Potter, The Earth Gazers: On Seeing Ourselves

Sometimes a little perspective is just what we need. Or a lot of perspective.

Bruno Latour, Down to Earth

Bruno Latour, Down to Earth

A book-length essay from a French philosopher who argues that politics needs to change with the climate—and that the most important part of that change should be a collective relinquishing of the pervasive political and social notion of “homeland,” so that we can all continue having an actual home.

Gregg Easterbrook, It’s Better Than It Looks

Gregg Easterbrook, It’s Better Than It Looks

The case for optimism on this list of doom and drought.

Robert Jay Lifton, The Climate Swerve

Robert Jay Lifton, The Climate Swerve

It is time, Lifton writes, to undertake “what may be the most demanding and unique psychological task ever required of humankind:” what he calls a “climate swerve,” which would create in us a “mind-set capable of constructive action.” We can make changes, he suggests, but only if we change our minds first.

Sunil Amrith, Unruly Waters

Sunil Amrith, Unruly Waters

A MacArthur Genius Grant recipient tells the social, political, and geological story of Asia through its rivers, coasts, and seas, and then in turn, looks to these to see how Asia might deal with our uncertain climate future.

C. D. Wright, Casting Deep Shade

C. D. Wright, Casting Deep Shade

Wright’s final book is a “memoir with beech trees,” but is also a history, an etymological dictionary, a cultural commentary, a philosophical text, a treatise on the notion of living. Read an excerpt of it here.

Robert Macfarlane, The Lost Words

Robert Macfarlane, The Lost Words

A celebration of the words disappearing from children’s lexicons—specifically, the Oxford Junior Dictionary, which recently did away with terms like “acorn,” “otter,” and “ivy”—complemented by gorgeous illustrations by Jackie Morris.

Gaia Vince, Adventures in the Anthropocene

Gaia Vince, Adventures in the Anthropocene

The “Anthropocene” is the name given to our current age: the Age of Man. In this book, Vince examines exactly what we’ve done with this planet we call home, and what we’re on track to do.

Paul Kingsnorth, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist

Paul Kingsnorth, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist

Kingsnorth was an environmental activist for many years—writing articles, participating in protests, speaking on panels—but though he still believes in the same principles he always has, he’s done with all that now; for some, he’s gone a little too far toward the darker side of the green movement. Read this collection, which includes the manifesto that became a movement, and see for yourself.

Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?

Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?

For generations, Australians have been taught the continent’s Indigenous peoples were primitive hunter gatherers, nomads who wandered from “plant to plant, kangaroo to kangaroo, in . . . hapless opportunism.” In Dark Emu, Australian writer and historian Bruce Pascoe forensically demolishes this myth. Drawing upon accounts by early settlers and explorers, Pascoe reveals the material sophistication of pre-invasion Aboriginal society, detailing widespread agriculture, extensive aquaculture involving complex systems of dams and weirs and permanent settlements incorporating wood and even stone structures.

For most Australians these discoveries have been revelatory, shattering long-held orthodoxies about Aboriginal culture and society. Yet Dark Emu is also a profoundly important contribution to a much larger reckoning with the violence of the colonial project. By exposing the degree to which knowledge of the achievements of Aboriginal society has been suppressed, it demands non-Indigenous Australians grapple Australia’s continuing marginalization of Aboriginal people and culture.

Equally importantly, Dark Emu underlines colonization has been an ecological as well as a human catastrophe. European agricultural practices, land-clearing and irrigation have all caused immense damage to the Australian environment, a process that is only hastening as global temperatures rise. Already the continent with the worst record of mammalian extinction, Australia’s recent history of extreme temperatures, bushfire, flood, coral bleaching and mass deaths of fish and other animals provide a terrifying glimpse of the future that is bearing down on us.

Avoiding the worst of what is coming is not yet impossible. And as Dark Emu makes clear, at least part of the model for a sustainable future lies in the knowledge and understandings embedded in Indigenous culture. In Pascoe’s words, “this is not a bleeding heart confection or adoration of the noble savage. It is prudent economic management and worshipful respect for the Earth itself.”

–James Bradley

David James Duncan, My Story As Told By Water: Confessions, Druidic Rants, Reflections, Bird-watchings, Fish-stalkings, Visions, Songs and Prayers Refracting Light, From Living Rivers, in the Age of the Industrial Dark

David James Duncan, My Story As Told By Water: Confessions, Druidic Rants, Reflections, Bird-watchings, Fish-stalkings, Visions, Songs and Prayers Refracting Light, From Living Rivers, in the Age of the Industrial Dark

22 essays about our reliance on and connection to water (and, of course, salmon). Anyway, who doesn’t love a good druidic rant?

Matt Hern and Am Johal with Joe Sacco, Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life

Matt Hern and Am Johal with Joe Sacco, Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life

In which three men road trip to the industrial tar sands of northern Alberta to talk to those whose lives are intwined (negatively or positively) with oil extraction, and wind up with a new understanding of ecology and what we need from our environmental politics.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor

Nixon uses the term “slow violence” to describe how disasters (like climate change) occur “gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” He suggests violence is typically spectacular, explosive, an event that makes better TV. But the kind of disasters that happen in the slow tick of time, they drift in the peripheries where it’s difficult to see or where we don’t bother to look, and their newsworthiness flickers in the headlines then retreats, which makes blame and consequence harder to pin down and even more difficult to voice. And voice is the very thing absented, invisible like the injustices and people themselves. So how do we get anyone to pay attention to such elusive nonevents that hardly make the news?

Nixon combines a critique of modern environmental literature, an examination of our “inattention to calamities that are slow and long lasting,” with an indictment about power brokers who offload their global toxins onto the poor of the world. This book is ballast to our listing ship of environmental storytelling and to the impoverished people who act as recycling units to the shit industry coughs up.

–Kerri Arsenault

Nicole Seymour, Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age

Nicole Seymour, Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age

An argument against the self-serious, self-righteous, and sentimental approach to climate change and environmental activism—and for an irreverent, alternative green politics, less likely to alienate everyone and drive us all insane with doom. I’m on board.

Tristan Gooley, How to Read Water

Tristan Gooley, How to Read Water

You’ve heard about navigating by starlight, but in this book, Gooley teaches you, among other things, how to navigate by puddle—something that may be extremely useful when the fallout from climate change destroys our society!

David Suzuki, The Sacred Balance: Rediscovering Our Place in Nature

David Suzuki, The Sacred Balance: Rediscovering Our Place in Nature

A 2007 text that argues for the necessity of understanding our essential connection to the planet. “‘Eco’ comes from the Greek word oikos, meaning home,” Suzuki writes. “Ecology is the study of home, while economics is the management of home. Ecologists attempt to define the conditions and principles that govern life’s ability to flourish through time and change. Societies and our constructs, like economics, must adapt to those fundamentals defined by ecology. The challenge today is to put the “eco” back into economics and every aspect of our lives.”

Wen Stephenson, What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other

Wen Stephenson, What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other

The story of a journalist who woke up to the urgent truth of climate change, quit his job and became an activist—and others like him, who have all confronted what he describes as “the spiritual crisis at the heart of the climate crisis.” After all, we’re all the ones who are going to suffer. You, me, and everyone we love.

Carl Safina, The View From Lazy Point

Carl Safina, The View From Lazy Point

It’s increasingly depressing to read and write about climate change books from years ago when nothing has yet changed. This is another that examines the deleterious effects that humans have had on the natural world alongside our apparent inability to effect any change of widespread change—but it’s a book that also makes sure to underscore the beauty and magic of the world we’re losing.

Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman, Climate Shock

Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman, Climate Shock

Two economists’ perspectives on climate change. Spoiler alert: they also think we desperately need to act.

Jedediah Purdy, After Nature

Jedediah Purdy, After Nature

An argument that “imperialism, racism, and gender hierarchy all came from the same arrogance as human subjection of the living world” and a call for “a Copernican revolution in ethical imagination” based in post-humanism.

J. R. McNeill and Peter Engelke, The Great Acceleration

J. R. McNeill and Peter Engelke, The Great Acceleration

A history of the Anthropocene and an explainer of same.

Charles C. Mann, The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Groundbreaking Scientists and Their Conflicting Visions of the Future of Our Planet

Charles C. Mann, The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Groundbreaking Scientists and Their Conflicting Visions of the Future of Our Planet

A double biography of Nobel Prize–winning agronomist Norman Borlaug and ornithologist William Vogt, the two scientists who discounted each other’s work but “were largely responsible for the creation of the basic intellectual blueprints that institutions around the world use today for understanding our environmental dilemmas.”

John Lewis-Stempel, The Running Hare

John Lewis-Stempel, The Running Hare

An environmentalist’s diary of a year spent farming wheat and wildflowers according to the traditional ways—undertaken in response to the dissipation of farmland in his native England.

Per Espen Stoknes, What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action

Per Espen Stoknes, What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action

“Understanding human responses to climate change is clearly becoming just as important as understanding climate change itself,” Stoknes writes in the introduction to this book. “The main question is: What do our reactions to the climate change facts tell us about the way we think, what we do, and how we live in the world? And how can we use what we know about human nature—our own, and others’—to move beyond our psychological barriers to making a great climate swerve?”

Zayne Cowie, Goodbye, Earth

Zayne Cowie, Goodbye, Earth

A book by a 9-year-old who knows enough to be pissed we’re failing to save the planet. Read the whole book here.

Dick Russell, Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Dick Russell, Horsemen of the Apocalypse

From the Koch brothers to Mitch McConnell, the men who are coming to destroy the world.

Peter Carter, Elizabeth Woodworth, Unprecedented Crime: Climate Science Denial and Game Changers for Survival

Peter Carter, Elizabeth Woodworth, Unprecedented Crime: Climate Science Denial and Game Changers for Survival

“Since the United Nations Paris conference in late 2015, climate change indicators have escalated so quickly than an emergency response is imperative if civilization is to avoid breakdown and eventual collapse,” the authors write in the introduction of Unprecedented Crime.

This book takes an unusual approach to the entrenched failure of governments and the media to act decisively and effectively to drastically curb CO3 emissions. The fact that no emergency response has been mounted by national governments is a crime against humanity and indeed all of life. To continue with business-as-usual at this late date is to knowingly, and therefore deliberately, compound this crime.

Lock them up, etc.

Alison Hawthorne Deming, Writing the Sacred Into the Real

Alison Hawthorne Deming, Writing the Sacred Into the Real

A philosophical biography-cum-travel narrative-cum-credo from a descendant of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Helen MacDonald, H is for Hawk

Helen MacDonald, H is for Hawk

The idea of “the wild” as fully discrete from the human world has long been a self-serving fantasy of those who would makes zoos of the jungle and gardens of the forest. Somehow, Helen Macdonald conveys this deepest of truths in her deeply intimate memoir of grief and hawking, a book that rightly won all the prizes and sold all the copies.

Camille T. Dungy, ed., Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry

Camille T. Dungy, ed., Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry

The natural world seen through the lens of 93 essential African American poets.

Dale Jamieson, Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed — and What It Means for Our Future

Dale Jamieson, Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed — and What It Means for Our Future

A philosophical look at climate change and our collective response to it.

George Marshall, Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change

George Marshall, Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change

“What explains our ability to separate what we know from what we believe, to put aside the things that seem to painful to accept,” asks Marshall in this cognitive take on the largest threat of our time. “How is it possible, when presented with overwhelming evidence, even the evidence of our own eyes, that we can deliberately ignore something—while being entirely aware that this is what we are doing?” I’ll tell you right now: whatever it is, it’s the reason we can tolerate death at all!

Jason W. Moore, ed., Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism

Jason W. Moore, ed., Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism

“The news is not good on planet Earth,” writes Moore in the introduction to this book, a compilation of discussions about climate change from critical scholars. “The work of this book is to encourage a debate—and to nurture a perspective—that moves beyond Green Arithmetic: the idea that our histories may be considered and narrated by adding up Humanity (or Society) and Nature, or even Capitalism plus Nature. For such dualisms are part of the problem.”

Charles Eisenstein, Climate: A New Story

Charles Eisenstein, Climate: A New Story

A gesture at correcting our attitude towards the natural world and climate change, by rejecting a utilitarian view of our home planet and re-embracing the truth of our interconnectedness.

Daisy Hildyard, The Second Body

Daisy Hildyard, The Second Body

“Every living thing has two bodies these days—you are flying into the atmosphere and back down to the ground right now, but you can’t feel it,” Hildyard writes in this book-length essay. The duality of experience—personal and global, individual and cog—is her subject, and it’s this we must truly understand if we are to relate to our planet as we should.

Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life

Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life

In which Moore investigates the intersections of the modern age’s most pressing crises—food, climate, work, and economy—and identifies a common problem: capitalism as an organizing principle, or “capitalism-in-nature” as opposed to “capitalism and nature.”

Edward O. Wilson, The Future of Life

Edward O. Wilson, The Future of Life

An outdated (2003) but still evocative call for preservation of a diverse global ecosystem from top evolutionary biologist Wilson.

Craig Childs, Apocalyptic Planet: Field Guide to the Future of the Earth

Craig Childs, Apocalyptic Planet: Field Guide to the Future of the Earth

Those scary landscapes from SF novels? Turns out they’re already here—just not where you live. Yet.

John Vaillant, The Golden Spruce

John Vaillant, The Golden Spruce

A compelling tale of environmental true crime and the green-tinged obsessions of Grant Hadwin, a born again lumberjack whose warped ideas of earth justice led him to chop down a one-in-a-million sacred Sitka Spruce in the Haida Gwaii.

Adam Winkler, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

Adam Winkler, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

An essential text for understanding the unprecedented rights of corporations in this country. And if you understand that, next you can think about how those rights—shocker of all shockers—have a great deal of bearing on how much they can affect climate change.

Davi Kopenawa, Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman

Davi Kopenawa, Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman

The “life story and cosmo-ecological thought” of Davi Kopenawa, shaman and spokesman for the Yanomami of the Brazilian Amazon, whose people have undergone endless cultural and environmental oppression, as translated by Alison Dundy and Nicholas Elliott.

Déborah Danowski, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Ends of the World

Déborah Danowski, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Ends of the World

In which philosopher Déborah Danowski and anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro evaluate the possible ends of the world as contemporary mythologies.

William E. Glassley, A Wilder Time: Notes from a Geologist at the Edge of Greenland

William E. Glassley, A Wilder Time: Notes from a Geologist at the Edge of Greenland

A geologist’s in-depth investigation of one of the last truly wild places on earth.

Aaron Hirsch, Telling Our Way to the Sea

Aaron Hirsch, Telling Our Way to the Sea

In which Aaron Hirsh and Veronica Volny take twelve students to a remote fishing village on the Sea of Cortez, to learn and explore and tell stories about “the places we live and know [that] have been scorched and destroyed.”

Linnea Axelsson, Aednan

Linnea Axelsson, Aednan

Linnea Axelsson’s Aednan, the Northern Sami word for “earth,” “land” and “ground,” is a nearly 800-page minimalist epic poem that reads like a novel and tells the story of the fate of the Sami—the indigenous people, traditionally reindeer herders, of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. It follows two Sami families in Sweden from the early 1900s to present day, and in addition to contending with the cultural erasure of the Sami and Sweden’s colonial history, it tells the story of the land: the importance of Indigenous ways of knowing and being, the natural and human cost of extractive violence when Sweden began to mine in the North, the legacy of displacement, and offers a way of thinking about nature in terms of connection rather than ownership. For readers of Layli Long Soldier and An Indigenous People’s History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz.

–Saskia Vogel

Helena Granström, Det Som En Gång Var (What Once Was)

Helena Granström, Det Som En Gång Var (What Once Was)

Our culture teaches us how to be human and, crucially, how not to be human, the mathematical physicist and writer Helen Granström argues. It’s from this standpoint that Granström makes her urgent plea to finally acknowledge what we are doing to ourselves and to confront why we are refusing to change. Nature, once our home, is now just a backdrop (see: influencers instagramming from California’s superbloom), and we are in the midst of a catastrophe. Together with photos from natural landscapes under threat in Sweden, Det Som En Gång Var (What Once Was) weaves together the story of a lone woman trekking through Swedish Lapland, forced to confront her ideas about “nature,” with an accessible and philosophical essay that explores technology, civilization and the wild, in order to ask how come, with all that we know, we continue to accept that our way of life is threatening our very existence? Searing and illuminating. With echoes of Naomi Klein and Rachel Carson.

–Saskia Vogel

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, Zoopolis

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, Zoopolis

Zoopolis by Donaldson and Kymlicka is the most important essay about animal rights since Peter Singer’s famous Animal Liberation. We know that animal farming is the main cause of global warming. It’s a necessity and our responsibility to change our behavior towards animals and to imagine a new system of cohabitation. In Zoopolis, Donaldson and Kymlicka propose a new political approach to animal rights and defend the concept of equal fundamental rights according to citizenship theory. Zoopolis is an instant classic, a necessary read, and a promise for the future of our humanity.

–Jean-Baptiste del Amo

Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, tr. Frank Wynne, Animalia

Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, tr. Frank Wynne, Animalia

The history of five generations of a single farming family in southwestern France, whose lives are dominated by the animals they keep—pigs—told in extraordinary, propulsive prose that evokes what it means to be human in this world, for good or ill.

Barbara Hurd, Walking the Wrack Line: On Tidal Shifts and What Remains

Barbara Hurd, Walking the Wrack Line: On Tidal Shifts and What Remains

Thoughtful essays inspired by shorelines from Massachusetts to Morocco.

Dianne D. Glave, Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage

Dianne D. Glave, Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage

Dianne Glave is an African American pastor and environmental historian whose book takes a look at the ways in which African Americans have interfaced with nature since the earliest arrivals of West African slaves. What farming techniques were used to survive slavery and Reconstruction? How did runaway slaves make use of natural resources in the unfamiliar environments their escape routes led them through? Though not explicitly about climate change, Rooted in the Earth is a contemporary work of black naturalism that debunks the misguided notion that African-Americans do not have a substantive history of conservationism.

–Aaron Robertson

Carolyn Finney, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

Carolyn Finney, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

In Black Faces, White Spaces, geographer Carolyn Finney uses film, literature and pop culture to analyze how key moments in American history (Jim Crow, the passing of the Wilderness Act in 1964, Hurricane Katrina, etc.) shaped its citizens understanding of the outdoors. Nature has long been commodified and racialized, and Finney suggests that these tendencies emerge from similar impulses. Finney chats with leading black environmentalists to understand exactly how the American wilderness became, well, so white.

–Aaron Robertson

Raja Shehadeh, Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape

Raja Shehadeh, Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape

In this volume, lawyer and human-rights activist Shehadeh presents an unusual and evocative way to consider the Palestinian-Israeli conflict: via six walks taken through the occupied territories between 1978 and 2006.

Erik Reece, Lost Mountain

Erik Reece, Lost Mountain

An up-close and personal view of the strip-mining of a mountain in Kentucky’s Appalachia between the years 2003 and 2004, and its decimation from a lush, biodiverse paradise to a dusty, barren hill.

Susan Murphy, Minding the Earth, Mending the World

Susan Murphy, Minding the Earth, Mending the World

A Zen teacher provides a “medicine kit” for dealing with the ecological crisis and—maybe—starting to heal the world with engaged Buddhism.

Stephanie Kaza, Green Buddhism

Stephanie Kaza, Green Buddhism

Buddhism-based strategies for mindful, ecologically conscious living from a Buddhist environmentalist.

Jean Jouzel, Claude Louris and Dominique Raynaud, The White Planet: The Evolution and Future of Our Frozen World

Jean Jouzel, Claude Louris and Dominique Raynaud, The White Planet: The Evolution and Future of Our Frozen World

An in-depth look at the planet’s ice (and lack of ice) and what it tells us about the past and future of climate change from three cryosphere specialists.

Dan Fagin, Toms River

Dan Fagin, Toms River

Toms River provides a blueprint for anyone interested in connecting the dots between environmental toxins and cancer, which is what Fagin sought to do. In short, in 1953 the chemical company Ciba opened its doors in Toms River, New Jersey and was welcomed aboard by residents who benefitted from its jobs, its tax revenue, and its generous donations all over town. The thing is, unbeknownst at the time, Ciba began using the Toms River as their dumping grounds, leaking toxic chemicals into the land and water and eventually into people’s DNA. Within twenty years, cancers started appearing in curious clusters. Using rigorous historical research, persistence (it took him seven years to write it) and a full toolkit of investigative reporting and science journalism, Fagin proves that books can inform a citizenry and simultaneously affect public policy and the world in which those citizens live. I met with Fagin after he won the Pulitzer for the book in 2014, and he said the most important thing a writer needs to do in this kind of project, “is above all, ascertain the truth.” Indeed.

–Kerri Arsenault

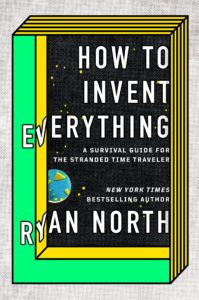

Ryan North, How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

Ryan North, How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

The premise of this book may be that it’s a guide to how to restart society (and/or giant wombat domestication) from scratch if you get stranded thousands of years into the past, but if the direst predictions about climate change are correct, survivors will have to be starting over from scratch only hundreds of years into our future. Maybe they’ll find a moldy copy of this book somewhere, and it’ll help them to figure out how to do it better next time.

Various authors, Trespass: Ecotone Essayists Beyond the Boundaries of Place, Identity, and Feminism

Various authors, Trespass: Ecotone Essayists Beyond the Boundaries of Place, Identity, and Feminism

Occupation and Peace? Containment and Wildness? Co-existence within borders? The women in this volume write breathtakingly beautiful and complex essays dealing with what Terry Tempest Williams repeatedly asks in her essay, “A Disturbance of Birds,” “How shall I live?” and “How shall we live?” Isn’t this another way of asking ourselves, how do we persevere in the midst of rupture? How do we repair and heal selves, families, nations, earth? Read this book. Let it in deep.

Rebecca Solnit, Savage Dreams

This early book by Rebecca Solnit draws the forces of destruction and conservation into the bloody shared history they’ve had in the West since the theft and conquest of land from indigenous tribes. Writing of nuclear testing and Yosemite, Solnit finds a Janus faced hypocrisy of complexity—nuclear testing is lethal yet it leads to the assembly of civil resistance, in essence creating as it destroys, while the establishment of Yosemite sometimes destroyed what it professed to preserve. Writing at the beginning of her career Solnit is already in full possession of her passionate, phenomenally informed and landscape obsessed voice. A must read for anyone who cares about the history of the American West.

–John Freeman