13 Books You Should Read This January

Recommended Reading From Lit Hub Contributors

Sam Lipsyte, Hark

Sam Lipsyte, Hark

(Picador)

Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land is one of the funniest books I’ve ever read. It was the first book I gave my fiancé, and it was 100% just a gift and not a humor test. If Lipsyte started writing sponsored content for air filtration devices, I would probably read it. Luckily, he published a new novel instead! Hark is a satire about an “unwitting mindfulness guru” (guru culture—endlessly fascinating!) who is ill-prepared for the messianic status he attains. I can’t wait to read it, then probably buy it for everyone as a thoughtful gift that is in no way a test.

–Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub social media editor

Sally Wen Mao, Oculus

Sally Wen Mao, Oculus

(Graywolf Press)

Sally Wen Mao’s poetry is at once speculative, sharp, lush, and precise. I fell hard for her debut, Mad Honey Symposium, a heady exploration of danger, desire, and drive, and I love the way she refracts her poetry through alternate perspectives. In Mad Honey Symposium, she draws on real-life news articles like a couple sick from mad honey and a group of children who eat azaleas, and often references the honey badger, an animal known to be fearless, powerful, and thick-skinned––an apt image to conjure repeatedly. Oculus tackles distance and exile, technology and time––several poems are told through the filter of a time-traveling Anna May Wong, the first Chinese American film star, which is all I needed to hear to zoom through space and time wherever she asks me to.

–Kyle Lucia Wu, Lit Hub contributor

Sarah Gambito, Loves You

Sarah Gambito, Loves You

(Persea)

2019 starts off with a much-needed infusion of new poetry from Sarah Gambito (it’s been ten years since her last book, Delivered!). I’m super-excited for Loves You because of its intersection between poetry and recipes, which shifts the focus both inward into family and nostalgia, and outward into culture, immigration, racism, and life as a person of color––how we’re both nourished and drained by daily life. January is about setting intentions, and I want to start my year with Loves You so my 2019 can be all poetry, recipes, and resistance.

–Kyle Lucia Wu, Lit Hub contributor

Dani Shapiro, Inheritance

Dani Shapiro, Inheritance

(Knopf)

A Rabbi once said of the conversional ritual bath (mikvah) that “one enters never having been a Jew and leaves always having been a Jew.” Shapiro’s Inheritance is a journey of conversion. Through a serendipitous act that reveals a secret, substance and placement is given to a life-long lacuna. This discovery leads her to probe, study, learn, become. Each discovered fact fills previously unidentified territory. She accommodates a biological, though initially vestigial, father whom she meets. She never replaces Paul, the man who has always been her father and clearly was a hero to her. She officially changes her first name, a name made-up by her mother that Shapiro admits to “hating” as a way of getting even with her mother for the lifelong lie. Shapiro works hard for clarity and inheritance. She emerges always having been that which seemed missing.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub contributor

Doug Bock Clark, The Last Whalers

Doug Bock Clark, The Last Whalers

(Little, Brown and Company)

Doug Bock Clark’s Last Whalers is a riveting account of an indigenous culture pinned between tradition and modernity. As with much in our current moment, a sense of loss permeates this deep journalistic foray into the lives of the Lamalerans, one of the last hunting and gathering cultures on earth, but Clark’s talent for capturing the full complexity of the people he writes about keeps the book afloat as it navigates the treacherous waters of the 21st century. This page-turning account of a culture on the verge of being capsized by the monoculture of global capitalism is an unexpected page-turning. I recommend it highly.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor

Laura Sims, Looker

Laura Sims, Looker

(Scribner)

In this brief, haunting novel, Sims chronicles the inner life of an unnamed woman going through—well, let’s just say she has a lot on her mind. Her central preoccupation is with a well-known actress who lives on the woman’s block. She collects the detritus of the actress and her family’s life, and fantasizes about becoming the actress’s friend and confidante. Alongside this obsession, though, she is overtaken by other negative thoughts about herself and what she holds most dear. Looker is a powerful sylph of a book about creation and destruction and the permeable boundary between them.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor

Julie Delporte, This Woman’s Work

Julie Delporte, This Woman’s Work

(Drawn and Quarterly)

This Woman’s Work is an illustrated autobiographical book and it reminds me of the work of Sheila Heti. There is a rawness or haphazardness to the narrative method that is part of what disarms the reader and leaves them vulnerable to flooring realizations, or even just new questions. This Woman’s Work is a smart, meditative, and gorgeously illustrated feminist essay named after a great Kate Bush song that uses the Finnish writer Tove Jansson as its central hero. What more do you need? This book will captivate and move you.

–Nate McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Jane Brox, Silence: A Social History of One of the Least Understood Elements of Our Lives

Jane Brox, Silence: A Social History of One of the Least Understood Elements of Our Lives

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

After the assault of holiday social gatherings and their concomitant sorties of festive selfies, January seems the perfect time for Jane Brox’s social history of silence to emerge. Silence is an element, Brox argues, that can serve as solace or punishment, an instrument of torture or control or one of redemption. She traces the contours of prison systems and their requisite acts of silencing, as well as the instruction of Thomas Merton, a hermit monk, who wrote, “I need solitude for the true fulfillment which I seek—that of being ordinary…In solitude, at last, I shall be just a person, no longer corrupted by being known.” From Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary to the Abbey of Gethsemani, one thing Brox illustrates is that silence is something we should discuss, even if within ourselves.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributor

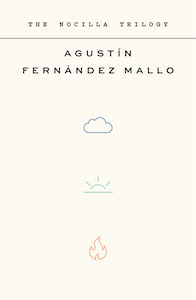

Agustín Fernández Mallo, The Nocilla Trilogy: Nocilla Dream, Nocilla Experience, Nocilla Lab

Agustín Fernández Mallo, The Nocilla Trilogy: Nocilla Dream, Nocilla Experience, Nocilla Lab

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

To call the works that comprise Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Nocilla Trilogy wide-ranging wouldn’t be inaccurate, but it would miss the mark in terms of just how much these books manipulate and revise concepts of language and narrative. They fall somewhere between Ben Marcus’s The Age of Wire and String and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights in their unpredictability, their sense of risk, and the utter joys that can arise from reading them.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

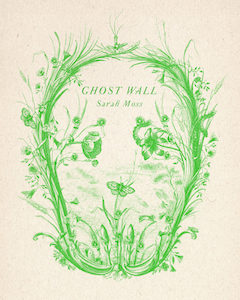

Sarah Moss, Ghost Wall

Sarah Moss, Ghost Wall

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Sometimes, usually when ads for Amazon’s creepy virtual assistant are playing, I think I want to flee the city and hide out in the woods where there is absolutely no internet or cell phone reception. But instead I think I’ll just read about what a return to these simpler times would look like in Sarah Moss’ Ghost Wall. In this story, a young woman joins her obsessive father and his anthropology students for their Iron Age reenactment. They use survival skills, work with primitive tools, and learn about rituals of the past—including the construction of a “ghost wall,” comprised of sticks and ancestral skulls. (Where does one even find these?!) I’m excited to see what happens next.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

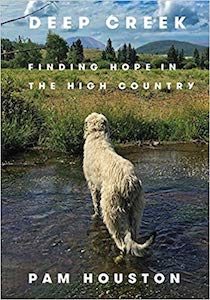

Pam Houston, Deep Creek: Finding Hope in High Country

Pam Houston, Deep Creek: Finding Hope in High Country

(W. W. Norton & Company)

Years ago, Houston’s “How to Talk to a Hunter,” from Cowboys Are My Weakness, sold me on her voice. Deep Creek is a song of grief, longing, and patient hope; a document of life—”It’s hard for anybody to put their finger on the moment when life changes from being something that is nearly all in front of you to something that happened while your attention was elsewhere.” Houston often returns to her 120-acre Colorado ranch as a place of structure, identity, and affirmation. Houston says she started the book “attempting to express my love for a piece of land that has defined the largest portion—by far—of my life.” When she, and the reader, arrive at the end of Deep Creek, the book is an attempt “to write my way to an understanding of how to be alive in the meantime, in the final days, if not of the earth, then at least the earth as I’ve known her. Because it has only been in knowing her that I’ve come to know myself.”

–Nick Ripatrazone, Lit Hub contributor

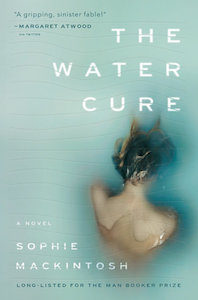

Sophie Mackintosh, The Water Cure

Sophie Mackintosh, The Water Cure

(Doubleday)

I loved this dreamlike, hypnotic novel, which is sometimes lovely but more often terrifying—there’s a lot of desultory sunbathing, and then suddenly we’re deep in one of several bizarre and violent rituals. The story concerns three sisters raised in obscurity, told that their bodies are dangerous—but not so dangerous as the world beyond their small island, and not half so dangerous as the bodies of men. But when men from that outside world do intrude, as of course they must in stories like these, the sisters begin to figure out the truth—of desire, of safety of their past, of their parents—for themselves.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

John O’Hara, Four Novels of the 1930s

John O’Hara, Four Novels of the 1930s

(Library of America)

When most people think of the great modernists, John O’Hara is not among the names that come to mind. That is unless you’re one of the “John O’Hara Cult”—a small group of O’Hara champions, like Fran Lebowitz, who once admitted, “To me, O’Hara was the real Fitzgerald.” In diving back into O’Hara’s work once more, I paid particular attention to his interest in surfaces. Somehow he finds in the surfaces, not some gloss or veneer that covers and pretties up his characters and their world, but the real that reveals itself through subtle movements and minor accoutrements, discreet disclosures and slight idiosyncrasies. In the surfaces he saw the depths, and in the depths he saw the surfaces. He wrote about surfaces to understand people, and he certainly understood people, writing about social class more directly and more vividly than almost anyone. He deserves his spot in the modernist pantheon.

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributing editor

Madhuri Vijay, The Far Field

Madhuri Vijay, The Far Field

(Grove Press)

The January book I’m looking forward to reading (while I still have the time before the baby arrives) is The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay. I’ve only had the chance to read an excerpt from Vijay’s debut and was quickly drawn in by the eloquent prose. Vijay’s main character, Shalini, sets out from her home in Southern India to a remote Himalayan village determined to find answers connected to the loss of her mother. It seems that what she finds is very different than what she initially thought. Vijay won the Pushcart Prize for her short story “Lorry Raja” in 2014 and I’m excited to experience her work at length in this debut novel.

–Melissa Ximena Golebiowski, Lit Hub contributing editor