The idea of a single day devoted to the earth is absurd. In the 49 years since the first Earth Day was celebrated, human civilization—checked by neither morality nor policy—has wrecked devastation upon the planet, increasing with each passing year of excess and inaction the likelihood that coming generations will live in a world unrecognizable to Senator Gaylord Nelson, who first conceived of the day as an environmental teach-in on April 22, 1970. But if there is any hope in righting this awful course, we need to think of every day as Earth Day.

With that in mind we have come up with the beginnings of a climate change library, 365 books that show us where we’ve come from, where we’re at now, how we might survive this crisis, and how we might cope if we don’t. With contributions from the likes of Richard Powers, Rebecca Solnit, Bill McKibben, Elizabeth Rush, Aminatta Forna, Maja Lunde, Francesca Angiolillo, Stephen Sparks, Amy Brady, Jean-Baptiste del Amo, and many more, this collection is neither exhaustive nor fixed, and with the help of readers and writers alike, we hope to add to it in the coming months (and years, if we can). Divided broadly—and subjectively!—into four sections, we begin today with some classics of the genre.

Featured art from Landscape Painting Now, edited by Todd Bradway, courtesy DAP.

![]()

Gilbert White, The Natural History of Selborne (1789)

Gilbert White, The Natural History of Selborne (1789)

Twenty years of detailed observations of the rural Hampshire parish of Selborne, southwest of London, told in charming epistolary form. As time capsules go, looking back 250 years at the natural world might as well be 2,000.

Susan Fenimore Cooper, Rural Hours (1850)

Susan Fenimore Cooper, Rural Hours (1850)

A well-worn classic of nature writing from the edge of the old frontier (upstate New York!); a compelling portrait of Cooperstown, New York.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854)

Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854)

A man, a plan, a pond. You probably know this one, the American ur text of walking out on polite society and writing about it. Walden spawned 10,000 imitators, some good, a few greater than the original, and the rest best left out in the woods.

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species (1859)

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species (1859)

The foundational text of evolutionary biology should be required reading for those of around for the downslope of the evolutionary process… (too dark?)

Mary Austin, Land of Little Rain (1903)

Mary Austin, Land of Little Rain (1903)

Mary Austin is a writer who seemed to walk around with her third eye wide open. In Land of Little Rain it’s the Great American Desert she wanders, from the Mojave to the Eastern Sierras, along the way overturning stones and names. Austin’s keen eye spotted great glinting doom of the American West early, for her time and place. Literature of the Anthropocene-heads will recognize her from a cameo in Mark Reisner’s essential Cadillac Desert, in which Austin confronts William Mullholland about his plans to steal Owens Lake.

–Claire Vaye Watkins

Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (1906)

Because human rights, animal rights, and the environment are so closely intertwined, The Jungle deserves a place on eco-fiction lists. Few industries are more abusive to human workers than factory farms and slaughterhouses, or more devastating to the environment. And the book is not as dated as it may seem; while food safety has certainly improved since The Jungle, the human and animal abuses are still prevalent, as is the pollution caused by animal agriculture. As groundbreaking as the novel was back in the early 20th century, The Jungle remains relevant today.

John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra (1911)

John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra (1911)

My First Summer in the Sierra describes John Muir’s first trip to California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, located in what is now Yosemite National Park. Muir, a young Scottish immigrant, joined a crew of shepherds and kept a diary while tending sheep over four months. He details vistas, flora and fauna, and other natural wonders. No one has advocated more for the preservation of wilderness in the United States than John Muir, who went on to co-found the Sierra Club. His 12 books—and hundreds of articles—mark him out as a key naturalist and nature writer. This book was brought numerous visitors to Yosemite with four million people now visiting each year. The Sequoia National Park was also created partially thanks to his work.

Rachel Carson, Under the Sea Wind (1941)

Rachel Carson, Under the Sea Wind (1941)

Climate change activists regularly cite Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) as the beginning of the modern environmental movement. When it came to ocean conservation, however, her first book Under the Sea Wind (1941), succeeds better in reminding us about the beauty and complexity of marine ecosystems. Not one line of this nonfiction masterpiece is antiquated. Indeed, the external lessons learned from Under the Sea Wind are will never be “gone.” As a biologist Carson studied the interrelationship of sea creatures more loving than anybody else. Carson’s Under the Sea Wind is divided into three scientifically exact sections: “Edge of the Sea” (a study of a migratory sanderling named Silverbar); “The Gull’s Way” (centered on a mackerel named Scomber swimming through a gauntlet of near-death experiences); and “River and Sea” (an ocean ecosystem as experienced by Anguilla the eel). Putting the reader into the life script of three lovable sea creatures Carson’s book should be required reading in American high schools. I hope the next U.S. president leads a global moonshot to save the world’s oceans from desecration with Under the Sea Wind serving as the foundational text.

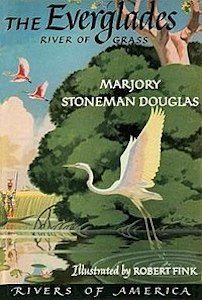

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, The Everglades: River of Grass (1947)

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, The Everglades: River of Grass (1947)

Published in same year as the opening of the Everglades National Park, The Everglades described how the wetlands were suffering and in need of restoration and preservation, positioning the Everglades as a national treasure at time when many people thought it was just a swamp.

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949)

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949)

In a series of essays, Aldo Leopold describes the land around his home in Sauk County, Wisconsin. He advocates for a responsible relationship between the land and people, enumerating the importance of striking a balance between the two and revealing the negative effects of removing one species, like a predator, from the natural order. He coined the term “land ethic,” asking that humans develop a new sense of morality in order to preserve ecosystems.

Gavin Maxwell, Ring of Bright Water (1960)

Gavin Maxwell, Ring of Bright Water (1960)

Ring of Bright Water details Gavin Maxwell’s experiences with otters at his remote house in Scotland. It’s an account of humanity with wildlife, and coming to understand nature. It shows that no matter how advanced we feel, we can always learn more about nature and animals and was turned into a film starring Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna in 1969.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (1962)

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (1962)

Silent Spring was revolutionary for documenting how unregulated use of pesticides adversely affected both the environment and humankind. With it, Carson challenged America’s chemical industry at a time when environmental activism was unheard of. The book was met with fierce criticism from major chemical producers, but it sparked the start of the US ecological movement and led to major media coverage about the negative effects of pesticides. The use of DDT was eventually banned in the US in 1972, and a worldwide ban followed. The book is still controversial today; many critics blame Carson for hampering agricultural production around the world and allowing millions to die from malaria (DDT was originally intended to control malaria among soldiers in World War II). Even today, it’s a shocking portrayal of how far corporations can go when unregulated.

Wallace Stegner, Wolf Willow (1962)

Wallace Stegner, Wolf Willow (1962)

Wallace Stegner is something of an anomaly in the grand tradition of wild and free American nature writing. Disciplined, hard-working, and practical, not only was Stegner a prolific novelist, naturalist, and biographer, he was also something of a lobbyist on behalf of the environment (activist doesn’t quite fit), affecting change within the political system, both locally and nationally. Wolf Willow is an impressionistic memoir of his boyhood on the high Saskatchewan prairie, elegy for a landscape that would stay with Stegner his entire life, informing everything after.

Farley Mowat, Never Cry Wolf (1963)

Farley Mowat, Never Cry Wolf (1963)

In Never Cry Wolf, Farley Mowat describes his experiences investigating the declining caribou population in the Canadian sub-arctic in 1948. At the time, it was believed that wolves were to blame; he discovered that they existed mostly on small mammals such as mice. He found that when wolves did hunt caribou, they kill the weaker, older, and sick animals, which benefits the herd by allowing the fittest animals to breed and increasing the speed of the herd’s migration. Instead, he blamed human hunters for the decline in caribou. The book is widely credited for discouraging the practice of culling wolves. Although several Canadian government bodies saw Mowat as a disruptive influence at the time, he’s regarded as an environmental pioneer today. The prose is highly readable and ideal for young readers brought up on children’s fiction where the wolf is big and bad.

Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire (1968)

Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire (1968)

Desert Solitaire is a collection of essays about life in the wilderness based on Edward Abbey’s activities as a park ranger at Arches National Monument in Utah in the late 1950s. He writes about damage caused by overdevelopment and tourism while also waxing philosophical, dwelling on the power and ruthlessness of the desert. His essays reveal that a desert area can be as fascinating as a forest or coastline and heavily criticized the US Parks Service for developing parks filled with highways, where visitors could drive-in and drive-out without truly experiencing the surroundings; in his mind, American culture was not in the least aligned with nature. The book is widely credited with putting the Arches National Monument on the map.

Dr. Seuss, The Lorax (1971)

Dr. Seuss, The Lorax (1971)

The first favorite book of every budding environmentalist. Still kind of sad after all these years. Possibly sadder.

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

Annie Dillard was only 28 when she wrote this seminal account of four seasons spent in relative solitude in Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountains. A diaristic mix of observations both internal and external, Tinker Creek’s spiritual dimension sets it in America’s Transcendentalist tradition (Edward Abbey called Dillard Thoreau’s “true heir”)—but it is Dillard’s wild and saintly voice that sets it apart.

Gary Snyder, Turtle Island (1974)

Gary Snyder, Turtle Island (1974)

Snyder’s 1974 collection of poems and essays inverts the typical centering of human life in the biosphere. He begins with a translation of a term many native tribes used for North America. Using Turtle Island instead of, say, America, Snyder argues, it becomes possible “to see ourselves more accurately on this continent of watersheds and life communities—plant zones, physiographic provinces, culture areas: following natural boundaries. The “U.S.A” and its states and counties are arbitrary boundaries and inaccurate impositions on what is really here.” Poem by poem, essay by essay, Snyder tries to look past such barriers and see clearly what calls North America home. Most of the characters actors and agents in this book are animals, gods, natural phenomena. Bears, hawks, magpies. Sometimes they are roadkill, sometimes they speak back. To read this book is to appreciate the diminishment that has fallen on to so much poetry from this continent when it interacts with nature. Here is not the poet looking at nature, but rather, the poet erasing himself, and then taking away the periscope, too.

What is thrilling about the book is we get to watch this happen, as in, Snyder hasn’t shown up shorn of illusions or the culture which made him. One of Snyder’s most often anthologized poems, “I Went into the Maverick Bar,” sings a psalm of familiarity to the kitsch and pageantry of the West’s shabby dominion over the land which it stole. But there’s work to be done, the poem famously concludes, work to undo the hold such things have on him. In poems like “Facts” we watch him educate himself across this book, poems like “The Real Work” reveal him, encountering new ways of seeing. Snyder has spent his lifetime doing this work, and in so doing has helped us see what is before us—what was before the US, what was vandalized and worse by its creation. If you haven’t read him, this book—which won a Pulitzer in 1975—is where to begin.

–John Freeman

*

Andreas Eriksson, “Coincidental Mapping,” (detail), 2013. Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Andreas Eriksson, “Coincidental Mapping,” (detail), 2013. Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery.

*

Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (1975)

Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (1975)

With this 1975 classic, Australian philosopher Singer changed the way we think and talk about animals by introducing the concept of “speciesism”: the systematic disregard for non-human animals that allows for chilling acts of cruelty against them. The foundational text of the animal liberation movement, and important in considering humanity’s relationship to the natural world.

Ann Zwinger, Run, River, Run (1975)

Ann Zwinger, Run, River, Run (1975)

Zwinger is to western rivers what Rachel Carson was to the ocean (not surprising, since they shared a literary agent). Run, River, Run is Zwinger’s account of her trip down the Green River, from its headwaters in Wyoming’s Wind River Range to its confluence with the Colorado River. It won the John Burroughs Award for Nature Writing in 1976.

In Zwinger’s narrative of the landscape through which the Green River flows, time folds in on itself, and history occurs simultaneously with the present. She deftly weaves together stories about the local Fremont Indians and historic exploration of and settlement in the region (Butch Cassidy’s hideout at Brown’s Hole, or the wagon train crossing at Sublette), with its natural history (plants, animals, river geomorphology), and even broader geologic history. “I feel no time interval, no difference in flesh between who stood here then and who stands here now,” she writes.

While Zwinger remains in the background, focusing instead on the land through which she travels, her luminous writing can’t help but connect you to the author herself. “ . . . Aspen here . . . form solid groves that gleam like some Mycenaean treasure just opened to the sun,” she writes. “The river becomes a way of thinking, ingrained, a way of looking at the world.”

Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975)

The Monkey Wrench Gang is what we talk about when we talk about eco-fiction—and while Abbey’s fascinating, comic, and adventurous novel was published in 1975, its influence has lasted for generations. The novel is credited with influencing direct-action organizations such as Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front, and it still captures the angst and helplessness of today’s activists. While I might argue that the characters in the book could be a lot more eco-friendly themselves (they hunt and litter among the lands they aim to protect), standing up for the wilderness that cannot protect itself (from industry, development, agribusiness) should never go out of style.

Bruce Chatwin, In Patagonia (1977)

Bruce Chatwin, In Patagonia (1977)

A classic, wonderful 1970s travelogue about a part of the world that may soon cease to exist—in its current form, at least.

Edith Holden, The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady (1977)

Edith Holden, The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady (1977)

This is an amateur naturalist’s diary for the year 1906 where the changing seasons are shown by changes in plants and animals in the English countryside. In it, Edith Holden uses text, including poetry, and illustrations of birds, plants and insects. It was first published in 1977 and became an immediate publishing sensation, although it was a personal diary and never intended for publication. It shows almost anyone can have an appreciation for nature, if they just take the time to look carefully.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain (1977)

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain (1977)

In the great and tangled genealogy of 20th-century nature writing, Nan Shepherd would be the wild, eccentric great aunt (Robert Macfarlane, for example, is one of her many spiritual nephews). The Living Mountain is an ode to Shepherd’s beloved Cairngorms—that inward range of druidically serious mountains that gather in the heart of the Scottish Highlands. At turns philosophically probing and scientifically precise, Shepherd’s book, written in 1944 but not published until 1977 was like a hidden blueprint for so much British nature writing to come.

–Jonny Diamond

Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men (1978)

Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men (1978)

The rapaciousness is what gets to you, destruction for the pleasure of it. In Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez writes of the wolf killers, “It was as though these men had broken down at some point in their lives and begun to fill with bile.” The early settlers went for the wolves first, slaughtering them to the point of extinction and often with ingenious barbarity, and they went for the land and over centuries the air and the oceans. Reading Lopez describe the viciousness with which men destroyed wolves, one is left with a sense of the soul of humankind at its most depraved, as yet unchecked.

–Aminatta Forna

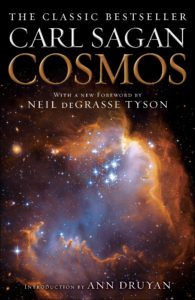

Carl Sagan, Cosmos (1980)

Carl Sagan, Cosmos (1980)

The mega-bestselling book that introduced millions of readers (and viewers, in its TV incarnation) to the facts of the universe. Of which we are a part. For now!

Jonathan Schell, The Fate of the Earth (1982)

Jonathan Schell, The Fate of the Earth (1982)

Jonathan Schell dedicated his life to peace during a militarist time. From his first book, drawn on reports on the US massacre at the village of Ben Suc, which he reported on age 24, to his last, a glimpse at how after seven decades, the threat of nuclear disaster had not left us, Schell chronicled the costs of this militarism on its victims, on societies, and in the ways it brought Americans to conceive of power and energy. While it’s not a book on carbon footprints or ice melting, his 1982 blockbuster, The Fate of the Earth is absolutely a book on climate change because it confronts the power to destroy the earth entirely. A power that has not left us, even if it has left the news.

To read The Fate of the Earth today is to realize how much more seriously this threat was taken during the Cold War. There’s an urgency and plainness to the writing that is startling. Much of its power proceeds from how Schell poses a question that is now at the heart of our moral failure to address climate change with real policy. “The possibility that the living can stop the future generations from entering into life compels us to ask basic new questions about our existence,” Schell wrote. “[T]hat the fruit of four and a half billion years can be undone in a careless moment—is a fact against which belief rebels.” As a publication, The Fate of the Earth became a key part of the disarmament movement. Would that he had lived to finish the book he was finishing upon his death—a book on climate change—perhaps the connection between peace and climate change would be clearer to us all.

–John Freeman