Our Favorite Literary Hub Stories of 2016

Some Beautiful Essays from a Very Bad Year

Over the course of 2016 we were very proud to publish an average of 30 features a week at Literary Hub. To see the ten most read stories of the year, you can head over here. Below, though, you’ll find the stories we loved best, the ones that stayed with us as editors—some of these reached the wide audience they deserved, some didn’t: such is the nature of the Internet. We loved them all, anyway.

Emily Temple, Associate Editor

Helen Chandler, “Marriage: Am I Doing it Right?”

This essay looks at marriage through the lens of art and art through the lens of marriage—the author’s marriage, to be exact. “My marriage is neither idyllic nor broken but there are cracks and there is joy,” Chandler writes. “It is neither weather nor meals. It is arguments about money. It is worrying about work. It is silent anxiety, periodic depression. Naps. It is wine, whiskey, gin. It is quitting smoking next week. It is often reading on the sofa, perpendicular on the sectional. It often feels like a dependency but I have no interest in knowing the cure.”

So, yes, this is a beautiful essay about art and love—which is the kind of sentence that doesn’t really mean anything, so here is what I mean: if you’ve ever been in love, or even just obsessed, or ever loved a work of art about love or obsession, this essay will slay you dead.

Gabrielle Bellot, “Why Calvin and Hobbes is Great Literature”

More than just an extended piece of nostalgia, Bellot tracks the intellectual pedigree and literary value of Bill Waterson’s beloved work, as well as her own changing relationship to the comic through the years. As she puts it,” Calvin and Hobbes endures as literature and art combined because it is both: it asks important questions without simplistically resolving them, revels in its own absurdities, and is filled with a deep understanding of people, of our swirling contradictions and complexities and conundrums. I love it as much in 2016 as I did two decades ago.” It’s long past time that Calvin and Hobbes was outed for the transgressive, boundary-pushing, truly beautiful work of literature that it is.

Rufi Thorpe, “Actually, All Writers Steal”

You know when you read something and it seems like it was written by the best, smartest version of yourself? That’s how I feel whenever I read Rufi Thorpe. This essay in particular makes me feel a lot better about ruthlessly plucking details from the lives of everyone I know, putting them in fiction and then, um, totally forgetting that I didn’t make them up. As Thorpe puts it, “There are some things so wonderful, so beautiful, or so terrible, that I feel they must be kept, pinned down, saved from the maw of oblivion. . . . I am a creature obsessed with remembering. I remember discovering when I was in my twenties and had no television that I could just lie in my bed and remember things for hours. This activity, this kind of deep, Proustian revery, is, I think, the bread and butter of most fiction writing.”

Jonny Diamond, Editor

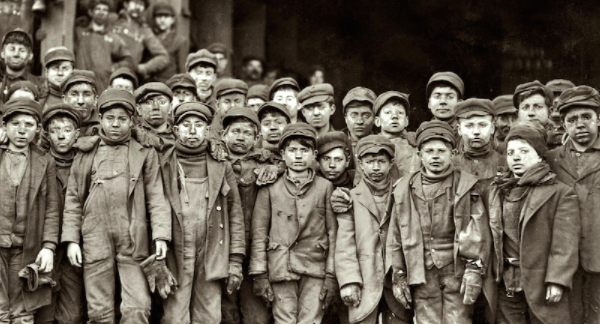

Elissa Washuta, “They Just Dig: On Writing, Coal Mining, and Fear”

To compare writing to hard manual labor in any meaningful way is, at best, almost impossible; at worst, it’s foolish and wrongheaded. Conceding this early on in her luminous, probing essay, the great Elissa Washuta goes on to do just that, summoning her coal-mining ancestors, their crushed bones and black lungs, their songs, their stories, and sets them to work alongside her extended metaphorical investigation of how words accrue from excavated memories. And where things could easily cave in under the weight of self-seriousness, Washuta maintains a light touch, even in dark moments:

If I do say it was hard, I pile on the evidence: in the beginning, I went from smoking casually to smoking more than a pack a day, waking up nicotine-starved and walking-pneumonia-sick. I could only write drunk, stuffed with potato skins.

Lina Mounzer, “War in Translation: Giving Voice to the Women of Syria”

This dizzyingly ambitious essay would be among my favorites even if Lina Mounzer hadn’t quite pulled off the narrative voice-shifts between her own and the tragic yet resilient chorus of Syrian women she undertook to translate. But she did, and the result is a profound document that bears witness to a slow-motion catastrophe from the inside and out, that interrupts our outrage-at-a-distance, and that demands each reader consider individual moral responsibility at a moment of great human suffering.

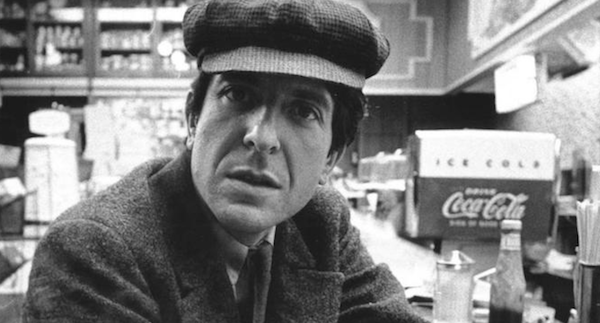

Summer Brennan, “Cohen Dies, Trump Wins, and We Will Sing About These Dark Times”

News of the great Leonard Cohen’s death came at a moment when most Americans (and much of the world) was reeling from the election of a vain, bigoted, jingoist former reality TV star to the most powerful position in the world. Somehow, amid her shock and sorrow, Summer Brennan was able to put into words how that felt.

Jess Bergman, Features Editor

Emily Harnett, “What About a Woman’s Right to Idleness?”

I’d probably be remiss if I didn’t mention Emily is a close friend and former roommate, but this would make my list even if it weren’t for the fact that I frequently refer to her as my wife on Twitter. Filtered through the frequently bed-bound stories of Leopoldine Core’s debut collection When Watched, this essay is a perceptive look at the way women’s creative labor is often dismissed as idleness—and how both have been historically demonized, tracing a lineage that stretches from Rousseau to Girls and Frances Ha.

Adam Haslett, “The Perpetual Solitude of the Writer”

Adam Haslett is one of contemporary literature’s most keenly empathetic writers on the subjects of grief and mental illness, and this essay proves no exception to that. Its scope, however, is ultimately even broader than that: Haslett sketches a profoundly moving philosophy of art and art-making grounded in human intimacy, a resistance to market values, and the struggle against existential loneliness.

Rachel Vorona Cote, “Are You an Anne Shirley or an Emily Starr?”

Though she admits to a childhood preference for L. M. Montgomery’s lesser-known heroine, Rachel Vorona Cote’s essay is, in the end, a paean to both Anne Shirley and Emily Starr—as well as a poignant look at the role models we crave in the trials of pre-adolescence and a sharp investigation into why certain representations of girlhood endure in popular culture more than others.

Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Valeria Luiselli, “This is How the World Ends?”

The brilliant Mexican essayist, and author of The Story of My Teeth, wrote about the terrible and confusing sense of collective grief felt in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, focusing, as just one example of how the country as we know it will be dismantled, on the probable annulment of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA): “Beyond quantifiable improvements, DACA gave people the freedom from living in fear. Taking back the life that has already been granted to them seems like cruelty of the worst kind: cruelty for the sake of it.”

Dwyer Murphy, “A Neoliberal Trojan Horse: Dave Zirin on the Olympics”

Dywer Murphy spoke to the left-wing, progressive firebrand and Sports Editor for The Nation, Dave Zirin ahead of the Rio Olympics and in the immediate wake of a period of intense political upheaval in Brazil. Zirin spoke candidly and passionately about how major sporting tournaments often end up “ushering in debt, displacement and militarization of public spaces” within the host nation: “Countries accrue debt coming out of the Olympics, but that burden tends to fall on the backs of the poor, not the wealthy. You have displacement, but that displacement actually can serve to gentrify cities. Olympic infrastructure tends to be put in working class areas, because rich people would never tolerate that disruption in their lives. Afterwards, those areas become developed and people get pushed aside.”

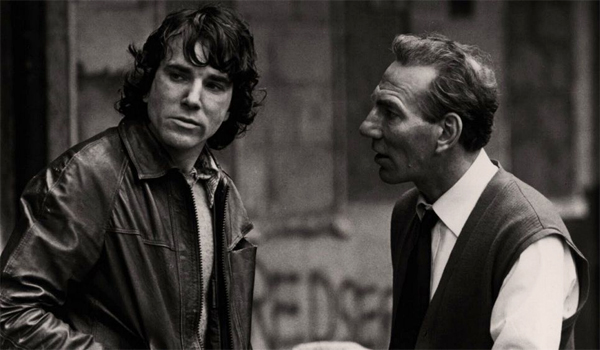

Terry George, “Turning a Book into a Movie is Like Making Booze”

In the Name of the Father, Jim Sheridan and Daniel Day Lewis’ 1993 film based on the notorious case of the Guilford Four, is a stone cold classic piece of cinema. Screenwriter Terry George’s brief but incident-heavy account of the trials and tribulations of creating a large-scale artistic project drawn from such a raw and recent political event, are frank, funny and insightful, not to mention relevant to the current climate: “It’s 20 years now since we made the film, but I think it’s a cautionary tale of what happens when a country goes into a frenzy of fear about real or perceived threats. When that happens, the law of the land starts to get bent and people are scapegoated.”

Blair Beusman, Associate Editor

A heartbreakingly beautiful essay in verse about the importance of creating art to survive the “ruthless, racist, misogynistic,/homophobic, fearful, litterbug,/wasteful, ungrateful, stingy, war/hungry, bloodthirsty, terrified/male fist” crushing our world. Writing is presented as a ritual though which one can transcend time and heal. I can’t read it without crying for the horror, the humanity, the profoundness, and the radical hope it contains.

Garnette Cadogan, “Walking While Black”

Garnette brings the unavoidable, quotidian nature of racism in America into sharp focus by exploring his lifelong love of walking, from his childhood in Jamaica to his college years in New Orleans to his adulthood in New York City. Almost immediately after arriving at college he learns that his mere presence is perceived as a threat, and walking becomes a “pantomime undertaken to avoid the choreography of criminality.” The contrast between the imagined danger of a black man walking alone and the very real danger of police brutality or bigotry-fueled violence illuminates the unfortunate reality of the current state of our country.

Gemma de Choisy, “Blair Braverman is Obsessed with the Things That Scare Her Most”

Gemma de Choisy, “Blair Braverman is Obsessed with the Things That Scare Her Most”

This piece contains some of my favorite things: nature, animal friendship, pictures of dogs, and an exploration of the ramifications of the limited, gendered way we view the world. Blair’s preference of the impersonal threat posed by wilderness over the intentional threat posed by humans (“A polar bear doesn’t mean harm, a polar bear wants food. Hypothermia doesn’t want anything; it’s a temperature. It’s only people who can want to hurt you for hurting’s sake.”) speaks volumes about humanity, and the distinction drawn between “tough girls” and “good men” as assumed anomalies is depressingly insightful. (RIP Queen.)