50 of the Greatest Summer Novels of All Time

This Year and Every Year

What makes a summer novel? It might be set in during a summer (One Fateful or otherwise), or it might be, for one reason or another, particularly appealing to read during the summer, or it might simply . . . feel summery. That’s right, I’m afraid the answer is: vibes. In other words: you know it when you see it.

So if you’ve already blazed through the season’s new books (good for you) or just prefer to read something no one else you know is reading (good for you!), but can’t decide what to put in your beach (good for you) bag, here are a selection of very good summer novels, as the Literary Hub staff defines them, published in any year other than this one.

NB: You’ll notice that this list skews “literary”—surely at this point no one need suggest that the books of Emily Henry or Elin Hilderbrand make for good beach reading, so hopefully you’ll find some less obvious suggestions here. (Which is not to say this list is wholly without obvious suggestions.) Also, there are plenty more books in this category, so as ever, if you are so moved, please add your own favorite novels to read during the summer to the list in the comments.

*

Renata Adler, Speedboat

In 2013, NYRB reissued Renata Adler’s 1976 novel Speedboat, and everyone was talking about it. It was modernist, told in vignettes, full of aphorisms; there was no plot; the characters were privileged and smart and caustic and did boring things like go to parties and speak about the essence of life. Cumulatively, the book somehow exposed the horrible reality of a bourgeois life you hate yourself for aspiring to. Jean Fein, our protagonist, is a reporter for a tabloid paper. She travels, has advanced degrees, teaches, takes Valium, sleeps with men, gets pregnant. There is therapy, there are cabdrivers, and the greatest little section about running away from rats. Which is all to say, this is a very New York novel, perhaps the most New York novel. And for me, the summer is always about New York.

I am a native Brooklynite, and therefore better than you. I have always made certain to spend the summer here, when the city is hot and horrible. Even as a kid, I’d look forward to August when all the rich people left for their cooler, bigger houses in the country or at the beach or some other unbelievable place, when my parents would delight in the availability of parking spots and the chance for us to eat together in empty restaurants. My summer read is not an escape, but a bedding in. Speedboat is the type of book you can read on the subway, each short section timed almost perfectly to last from Dekalb to West 4th; or you can read it in its entirety one perfect afternoon, sitting at a terrible aluminum patio table, switching chairs to stay out of the direct sun. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Jacqueline Susann, Valley of the Dolls

Who gets to decide the definition of a “summer read”? For me, summer reading isn’t so much a chance to shut off my brain, but an opportunity to lose myself in another world. When I pick a book to read at the beach, I want to be entertained by the storytelling as much as I want to dive into the depths of the human condition. Jacqueline Susann’s best-selling 1966 novel, Valley of the Dolls, has it all: sex, scandal, a dashing English playboy who (I imagine) looks like Cary Grant, glamour, stardom, and DRAMA. Susann’s debut centers on three young women who are hoping to make it on their own terms. Anne Welles is a Radcliffe-educated beauty from Massachusetts who moves to New York City to escape her judgmental hometown. Seventeen-year-old Neely O’Hara (birth name: Ethel Agnes O’Neill) is a lifelong vaudeville performer aching for Broadway acclaim. Jennifer North is an up-and-coming blonde bombshell whose looks rival Marilyn Monroe.

The three women have very little in common, but their professional and social circles collide, resulting in a bond born from the shared understanding of what it means to exist as a woman under patriarchal rule. Each woman seems to simultaneously play into and revolt against their archetype: Anne is a bookish “good girl” who, like Belle in Beauty and the Beast, craves adventure, excitement, independence, and true love. Neely, supposedly modeled after Judy Garland, is the child star who grew up too fast and dreams in dollar signs and bright lights. Jennifer, echoing the tragic legacy of Monroe, battles against the stereotype of the “dumb blonde,” but ultimately succumbs to defeat.

I know most people of discerning literary taste probably dismiss the novel as “chick lit” or a “low-brow soap opera,” but to reduce Susann’s work to such one-dimensional labels trivializes its cultural impact. Before we were wondering if women could truly have it all, Susann offered a satirical yet recognizable portrait of heterosexual womanhood. Perhaps not in the sense that the three women were “relatable,” but they deal with the same issues that impact women today: body image, gender roles, sexism, the pressures of aging, and misogyny. This isn’t to say Susann was focused on redemption arcs. Most of the men in Valley of the Dolls are cheaters, liars, or both—damaged goods who wholly subscribe to the Madonna/Whore complex. Many of the women are status-obsessed and needy, quick to backstab other women to reach the top.

Dolls, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2016, was never meant to be a feminist awakening. According to Susann, the book “showed that a woman in a ranch house with three kids had a better life than what happened up there at the top.” Critics panned the book; Gloria Steinem notably titled her New York Herald Tribune review “A Massive Overdose.” Regardless of the novel’s positioning as a now-dated cautionary tale, its campiness is irresistible. The 1967 film adaptation is just as campy and features Sharon Tate as Jennifer. Patty Duke provides an unforgettable turn as Neely (truly iconic scenes: flushing Helen Lawson’s (Susan Hayward) wig down the toilet; screaming her own name in a deserted alley).

Both the film and source material are first-rate escapism, eschewing the notion of “likeability” for memorable characters who would rather die than beg for empathy. –Vanessa Willoughby, Assistant Editor

André Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

Nothing says summer like intense romantic obsession, gut-wrenching interiority, languid afternoons and . . . yes, juicy peaches. Anyone who has ever been a teenager with too much time on their hands will recognizing the racing mind of Elio, who is spending the summer with his parents at their Italian villa (like you do) when he meets the older Oliver, who is so alluring that the beginning of the novel is mostly taken up with Elio’s frantic attempts to put a finger on him (metaphorically and literally), obsessing over the tiniest details, like the color of his palms (“almost a light pink, as glistening and smooth as the underside of a lizard’s belly. Private, chaste, unfledged, like a blush on an athlete’s face or an instance of dawn on a stormy night”). The novel is all like that—repeated ecstatic descriptions of minute ecstatic moments, all of it infused with the knowledge that it will end all too soon. Again: nothing says summer. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Charles Portis, Norwood

I always recommend True Grit, with its perfect first paragraph (and pretty much perfect everything that follows), and surely it is good for any season, but perhaps for a dedicated summer read you’d like a road trip novel, in which case, try Portis’s debut, a delightfully surreal tale about an ex-Marine who travels, mostly by bus, from Texas to New York City, to find someone who owes him $70. Americana and strangeness abound. –ET

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, The Love Songs of W.E.B Du Bois

Some of us (not parents) seem to have extra time in the summer—even if it’s only extra sunlight. Which makes this the perfect time to sink into a big (in this case 800+ pages), juicy, gorgeously written (in this case by a poet) American epic, which manages to wrap up decades of history in the engrossing story of one family. One of the most convincing recent contenders for the title of “the Great American Novel.” –ET

Malcolm Lowry, Under the Volcano

I first read Under the Volcano during the darkest part of a Montreal winter, snowed into the fourth floor of a tiny walk-up apartment that seemed to deny even the possibility of natural light; Lowry’s dizzying, elliptical account of fallen British diplomat Geoffrey Firmin’s day-long mezcal bender, in the bright and blurry streets of Oaxaca City, was about as close as I got to sun for a week. A decade later, I took the same fat and pulpy paperback copy with me to the Yucatan and read it all again; and though I was in a very different part of Mexico I was at least able to feel the same kind of sun, drink the same kind of mezcal as Firmin, if somewhat less burdened by thoughts of mortality and infidelity.

Under the Volcano was written to be reread: Lowry, whose booze-sodden, allusive modernism blossomed in the isolation of his own alcoholism, wrote the book so you could start reading at any point, the “story” built around not much more than the tidal pull of Firmin’s sadly compelling consciousness. And if there is sunshine in the book, it is there to render the shadows that much darker: the nearby mountain, the Second World War, the end of a marriage, the nearness of death, the oblivions of alcohol… Obviously, it’s the perfect beach read! (Look, my son’s middle name is Lowry.) –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Tove Jansson, The Summer Book

Jansson’s beloved novel is a series of gently funny, beautifully written vignettes about the life of a little girl and her grandmother on a small Finnish island. The perfect thing to dip in and out of, to set down and pick back up, to carry around for extra joy and solace in spare moments. –ET

Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock

Talk about vibes. Lindsay’s swoony, mysterious novel about a group of boarding school girls who disappear without a trace from a day trip to Australia’s Hanging Rock in 1900. Though the cut final chapter, which (sort of) explains what happens to them, has since been published, the whole thing still feels like a tantalizing mystery. –ET

Sarah Schulman, After Delores

As far as summer reads go, Sarah Schulman’s 1988 novel After Delores, the gripping, fast-paced story of a lesbian woman on a revenge mission against the girlfriend who betrayed her, might be a bit of an unusual pick—but it’s a book I associate with the season. Maybe it’s the way the narrator moves at a fevered pace around New York City’s Lower East Side, plotting and flirting, heartbroken and enraged, at a level of intensity best matched by the heat of summer—that is, when she’s not drinking from the corner of some forgotten bar, lost in daydreams and memories, a mood to fit the energy crash of a summer afternoon fading away. When it was published, After Delores brought readers into the emotionally anarchic world of a community that was invisible, disregarded, and disrespected by the mainstream, showing the consequences that this abandonment had for its members. It is as revealing now as it was then, in addition to being a suspenseful, thoroughly engrossing read for summer. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Jeffrey Eugenides, The Virgin Suicides

It takes place over a whole year, and maybe I’m influenced by the hazy sunlight of Sofia Coppola’s interpretation, but there’s something very specifically summer about the kind of obsession and deluded romance that Eugenides so convincingly portrays here. –ET

Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

Besides being gripping and immersive and strange like the best (and worst) summer nights, this novel could make the list for the rhododendrons alone. –ET

Terry McMillan, Waiting to Exhale

The contemporary classic was one of the earliest breakthrough novels to focus on middle-class Black women’s friendships—but its historical importance isn’t the real reason to read it. The real reason to read it is that it’s a delightful, irreverent, and sometimes raunchy novel about figuring it out (or not) with your friends—and a welcome hit of 90s nostalgia for those of us who are into that sort of thing. –ET

Sharma Shields, The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac

I went through a pretty intense Sasquatch phase the summer when I was ten (what, you didn’t?), so when I stumbled on The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac as an adult, I bought it on the title alone—and can I just say that I’ve never had less of a clue of what I was getting into with a book, and never been more pleased about it? The novel opens with nine-year-old Eli Roebuck watching his mom walk off in the woods with Mr. Krantz, a large, hairy man who sure seems like he might be Bigfoot—and then it spirals out over sixty years and four generations, as Eli’s obsession with finding Mr. Krantz/Sasquatch affects every relationship for the rest of his life—most notably, with his two wives and two daughters.

Each character gets their own parable, or fairy tale, or horror story, because they all have their own supernatural forces to contend with, from tentacled lake monsters to ghosts to Elusive Dads, which creates a structure that’s both propulsive and conveniently suited to breaking between chapters for a swim or a nap or whatever it is people do on vacation. Beyond being weird in the best of ways (a perfectly suitable metric, but only one on which this novel succeeds!), it’s also a deeply moving portrait of family and abandonment and the chaos we create from being, well, all too human. –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Lauren Wilkinson, American Spy

Summer is always the best time to curl up with a good page-turner, and Wilkinson’s brainy, original take on the Cold War thriller, inspired by true events, checks all the genre’s boxes and then some. –ET

Ray Bradbury, Dandelion Wine

Bradbury’s most personal (and least pyrotechnic) work, a gentle and engrossing novel of loosely connected stories about a 12-year-old boy’s fleeting summer in 1928. –ET

Salman Rushdie, The Ground Beneath Her Feet

Maybe ten or eleven years ago I booked a cheap, weeklong holiday to a small tourist town in Spain with my brother and two of our friends. It was at the tail end of a summer in which we had done nothing, achieved nothing, enjoyed nothing, and we were trying desperately to salvage some joy from the watery dregs of the season. By the time we arrived, however, the town had pretty much shut down for the year. There were no potential love interests left in the bars, nobody offered to rent us jet skis or take us water skiing, and the sun refused to shine on our pale Irish bodies.

Everyone was miserable. Everyone, that is, but me. Why? Because I had my copy of Salman Rushdie’s 1999 novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet with me, of course. While three-quarters of our party stomped around the rented apartment moaning about the trip being “a complete waste of time and money,” “the worst, most embarrassing holiday ever,” and “a load of shite,” I lay on the sand and read the entirety of Rushdie’s epic, sprawling, big-hearted 20th century rock n’ roll reimagining of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. It was delightful. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor in Chief

Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

It’s no secret that I’m obsessed with The Talented Mr. Ripley. It’s a book that reminds you how easily beautiful exteriors can hide deteriorating insides. But really, it has everything you could ever want in a summer novel: steamy Italian beaches, complex love triangles, travel, boating excursions, murder, impersonation, murder, escaping by the skin of your teeth and feeling pretty good about it, actually. But more importantly, it is compelling in the best way: Ripley is an intoxicating character, even (especially) in his amorality, and you find yourself wanting him to succeed, no matter what he does—and more than anything else, wanting to keep reading, no matter what’s going on around you. And not for nothing, I think of it every time I’m squirming around on the floor of my apartment, trying to catch the sunlight on my body, so that my stomach isn’t too pale when I meet my friends on the beach. That’s a normal thing to do, right? –ET

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

Love, murder, wine, Paris, swooning, hand-wringing, desire, shame—essential summer reading for brokenhearted and blossoming lovers alike. –ET

Quan Barry, We Ride Upon Sticks

Sure, it mostly takes place during the school year, but this is such a fun, nostalgia-soaked romp of a novel that it doesn’t really matter. The vibes are on point: witchcraft and sports and teenage angst and the unholy, enduring power of Emilio Estevez. –ET

Melissa Bank, The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing

I first read Melissa Bank’s collection of linked short stories the summer after seventh grade, because I saw it advertised in a women’s magazine I read on the floor in Barnes & Noble, and carrying it up to the cashier at the same Barnes & Noble made me feel impossibly sophisticated. I’d say, conservatively, that about 75 percent of the references—to literature, to sex, to The Rules, to working in publishing—went right over my head, but I when I got one, (like when Jane, the protagonist, threatens to report her boyfriend for “work harassment in a sexual place” when he badgers her about her job search in bed), I felt like I was in on something glamorous and grown up and exciting.

Which is what I remember most about those early teenage summers: getting to try on adulthood, with none of the responsibilities. I recently re-read The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing after many years, and was delighted to discover that it retains much of the magic, even as I reside full-time in adultworld (and get all the references). It has the feel of a smart rom-com—sharp, spare, and breezy—and it takes place entirely over summers. In short, it’s seasonal perfection, whether you’re a disaffected youth or a disaffected geriatric millennial. –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Rachel Ingalls, Binstead’s Safari

Reader, meet Millie. She’s the too-often-ignored wife of a boring, egocentric academic. His studies bring them on a safari through Africa, in search of lion myths. While he’s off doing research for his stupid book, Millie is having the time of her life. Sometimes a woman needs a vacation! She gets a haircut, she buys some new clothes, and she struts down the streets with a brand new attitude, charming everyone she encounters. Much to the dismay of her husband, she’s even caught the eye of someone better. (“The sound of his voice came to her hardly as part of the exterior world, but as though inspired within herself, like the beat of a second heart.”) Essentially, Rachel Ingalls was the first one to say Hot Girl Summer. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Margarita Liberaki, Three Summers

Along with the bright and fevered rush of summer, the season for me has always been tinged with the knowledge that it will end: it will come again, but you will be older, things will have changed, you will never be as young as you were. This is so sad, this cannot be, but this is life. Reading Three Summers is a relief to know someone else feels the same as I do: the translated Greek novel follows three sisters through three summers, as they love and lose and adapt to adulthood, the come down that is the loss of innocence. It’s funny, insightful, and a perfect summer book to balance out the beach reads and murder mysteries. I can’t recommend it enough. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Edward P. Jones, The Known World

Sometimes you just want to sink into a big, moving, brilliantly written historical novel, the kind of book you’ll look up from to find that somehow hours have passed in the real world and you didn’t notice. In fact, it is Jones’s delicate and innovative use of time that makes The Known World, which takes as its subject the life and legacy of a Black slave owner in antebellum Virginia, a forever classic. –ET

Richard Hughes, A High Wind in Jamaica

In which the children of an English family living in the heat of post-Emancipation Jamaica (“not a naked fish would willingly move his tail”) are sent, after a hurricane destroys their home, on a merchant ship back to England—a ship that is soon captured by pirates, which is not entirely unpleasant for (most of) the children. In fact, the whole thing soon takes on a distinctly surrealist air, especially in the prose, which is a constant delight (despite some outdated language and attitudes), but its wackiness is frequently pinned to the deck by moments of violence, sadness, and profound truths about the nature of experience. It’s the kind of book that makes me remember how much I liked reading before I did it for a living. –ET

Edward St Aubyn, Mother’s Milk

Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels are dark, funny, and beautifully written; and the fourth book in the five-book series, Mother’s Milk, takes place over four successive Augusts on the Melroses’ summer vacations. Each section is told from a different character’s point of view—Patrick and Mary’s five-year-old son Robert; Patrick, now in his early 40s and no longer a heroin addict, who drinks a lot instead and justifies his mid-life crisis affairs; Mary, who has devoted herself so entirely to the care and wellbeing of her sons that Patrick is an afterthought; and then, finally, the whole family. The title, in St Aubyn’s usual mix of witty and a bit cruel, forefronts the role of mothers, their either unlimited (in the case of Mary) or twisted (in the case of Patrick’s mother) capacity for love. And in typical holiday vacation situation, nobody is having a very good time. –EF

Kobo Abe, tr. E. Dale Saunders, The Woman in the Dunes

I love to recommend this novel—in which a man is kidnapped by a mysterious community and forced to live at the bottom of a hole in the sand, forever digging to prevent its collapse—as a sort of anti-beach read, because, you know, it doesn’t exactly make you want to go wandering off into the dunes. But it’s so hypnotic, and so weirdly funny, that despite its bleakness it’s actually kind of perfect to read on vacation. As long as someone knows where you are. –ET

Carson McCullers, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

“Deep in the heart of Summer, sweet is life to me still, / But my heart is a lonely hunter that hunts on a lonely hill.”

Yup, this line from William Sharp’s (aka Fiona MacLeod’s) 1901 poem “The Lonely Hunter” is where Carson McCullers got the title for her canonical novel of small-town southern life, which for many readers is really just a novel of small-town southern childhood. That’s because the most memorable character by far in the ensemble cast is the young teenage tomboy, Mick Kelly, whose longing for—and curiosity about—the wider world recalls to us what it meant to yearn for something we couldn’t possibly understand.

And though the novel’s action isn’t limited to a single summer, its pivotal scene—one of the most beautiful in American literature—has Mick Kelly sat beneath the window of a house on the rich side of town, drawn to the miraculous (and new to her) music of Beethoven on a gramophone, playing in transportive counterpoint to all the rich sounds of a summer night in Georgia.

And if you’d care to dispute the idea that The Heart is a Lonely Hunter doesn’t count as a summer novel, allow me to draw your attention to the first half of the couplet above, which is maybe the best possible distillation of what makes McCullers’ 1940 masterpiece so achingly beautiful. –JD

E.M. Forster, A Room with a View

A Room with a View (the first Forster novel I ever read), was the first book I thought of for this list. The thing is, I don’t remember if it literally takes place in summer (although it partially takes place on Summer Street!), but it feels like it, to me. It’s about a group of Edwardian British tourists on an excursion to Florence where some of them (the younger folks among them) wind up feeling things and become changed, and then wind up having to confront all this when they return to real life in England, later on. So… discovering one’s passions while on vacation in Italy? Seems like a summertime story to me. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads associate editor

Vendela Vida, The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty

I am here from the future to tell you to read this one on the beach (or some equally sunny location), a thought I had mere paragraphs into reading; unfortunately I couldn’t bring myself to set it aside, but you have a chance! Told in one long, hypnotic take—in a shockingly successful second person POV, no less—it’s the story of a woman traveling alone to Casablanca, who loses all her identifying documents and so starts to take on the identity of others. Her longest con is as a stand-in on set for a famous American actress, which might be my new career goal. Simmering and tense yet wickedly funny and at times devastating—sounds like a day at the beach, yes? –ES

Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing

Summer, despite its reputation for brightness, is prime time for hauntings. This brutally beautiful novel is full of ghosts both literal and figurative, plus a road trip, secrets, swamps, and—like summer itself—time that slips and bends and pulls us up short when we’re least expecting it. –ET

Douglas A. Martin, Outline of My Lover

This slim novel, the story of an obsessive love between a young man and the older musician who keeps himself at a distance, is a pitch-perfect summer read: it’s intense, sexy, gratifying even while it’s breaking your heart. Douglas A. Martin captures that specific moment in which you will do anything to keep a particular person in your life; as his narrator submits to desire, his story becomes one of wandering, shifting identity, and the moment-by-moment calculations of an intense, unstable love.

As Hugh Martin writes in his introduction to a recent Nightboat Books edition of the book, he takes on “a rarely articulated position: the cunning pathétique, whose acts of submission are as calculated as they are genuine. He gets what he wants by becoming what is wanted.” A classic of queer literature and an inventive, gripping story, it’s a good choice for the season. –CS

Lydia Millet, A Children’s Bible

There is a narrative tidiness to the summer novel, fitting as it does so neatly between seasonal signifiers of rebirth and death. And I’d wager that a disproportionate number of summer novels feature children at their center for similar narrative simplicity: who better to inhabit the full world of a single season than characters for whom it means so much?

Which leads me to Lydia Millet’s riveting (and funny) dystopian tale of one summer in the lives of an apostle’s dozen of wayward children. Basically abandoned by their affluent, checked-out parents while on a multifamily vacation at a sprawling country mansion, the young heroes of A Children’s Bible must reckon with the failure of the older generation as they confront a devastating weather event that tips the northeast into something approaching a Hobbesian nightmare.

Millet, as ever, has the lightest of touches with the heaviest of subjects, drawing out comically imbalanced intergenerational relationships fueled almost entirely by scorn. But insofar as A Children’s Bible also serves as a clear analog of the absolute mess that older generations have bequeathed today’s youth, it reminds us that winter, eventually, is coming. –JD

Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones’s Diary

Everyone knows that Literary Hub is firmly on the side of Bridget Jones’s Diary, one of the funniest novels ever written, and somewhat unfairly shunted to the side as “chick-lit” (not that such a designation hurt its sales any). With Bridget by your side for summer reading, you can have your cake and eat it too—it’s a breeze to read, but unlike with plenty of books marketed for this time of year, you won’t be wolfing empty calories. –ET

Jane Bowles, Two Serious Ladies

Contemporary novels about women on a strange spiral into depravity wish they could be this insane; in Bowles’ under-the-radar Modernist classic, both Miss Goering (unlikeable from birth), and Mrs. Copperfield (respectable in every way), are moved to slip the shackles of convention, mostly by sleeping with people they shouldn’t (a gangster, a teenage prostitute). “In order to work out my own little idea of salvation I really believe that it is necessary for me to live in some more tawdry place,” Miss Goering says. Is this novel about salvation? It depends on how you squint; either way, it will be a funny and mysterious companion on whatever semi-reasonable summer adventures you have planned. –ET

David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas

Like a tasting menu for novel styles; a good choice to bring on vacation when you really can’t decide what you’re going to be in the mood for, but want to be fully engrossed in what you’re reading nonetheless. –ET

Alex Garland, The Beach

Nothing says summer like a nice beach, and there are few literary beaches beachier than the titular beach from The Beach. Beach. Alex Garland’s 1996 debut—now rightly considered one of Gen X’s Mount Rushmore novels—is the darkly hallucinogenic tale of a restless English backpacker’s search for a fabled island paradise off the coast of Thailand, and the nightmarish unraveling of the utopian community he discovers therein.

I, like thousands upon thousands of similarly gormless Banana Pancake Trail-ers, read The Beach while backpacking around Southeast Asia. It was the summer of 2008, and I was young and wild and free… sigh… Anyway, The Beach holds a special place in my heart, as does the flawed-but-fun 2000 movie adaption. I heartily recommend both. –DS

Italo Calvino, The Baron in the Trees

A book that simply demands to be read outside. –ET

Colson Whitehead, Sag Harbor

Sag Harbor is the ultimate “becoming someone else over the summer” novel. It is the story of fifteen-year-old Benji and his brother Reggie, two affluent teenage brothers spending their summer vacation in the idyllic Hamptons-adjacent beach town of Sag Harbor. There, they cross paths with many of the friends and classmates from their fancy Manhattan prep school, all refashioning themselves into their carefree vacationing alter-egos. It’s the summer of 1985. There are no parents around. Benji, a nerd still in braces, wants to be cool. It’s long understood that this, Whitehead’s third novel, was a more personal project than his previous two novels—a retelling of his own teenage years growing up in these wealthy New York communities, and what it means to be a Black teenager in these mostly white spaces. –OR

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

It’s not exactly light, breezy reading, but hear me out—besides being set in the appropriate season, with the titular lighthouse a promise and a boat ride away, Woolf’s novel is an exercise in both busy excitement (everyone’s consciousnesses filling the pages, overlapping and infecting each other) and the lack thereof (the emptiest house in all of literature). It’s also as sad as we sometimes forget summer can be. –ET

Kevin Kwan, Crazy Rich Asians

For pure, unadulterated fun, you want Kevin Kwan’s satirical literary rom-com, set among the richest of the Singaporean rich, and concerning (of course) a lavish wedding. –ET

Patrick Modiano, translated by John Cullen, Villa Triste

A quintessential Modiano novel, and an utterly, fantastically specific summer novel layered with memories, mysteries, and inchoate desire. As with nearly all of Modiano’s fiction, we follow a man’s interrogation of his own past, in this case a peculiar summer spent hiding out (or was he?) in the area of Lake Annecy, a resort area seemingly in a state of perpetual vanishing, its chic impossibly lost, its magic dwindled, its mainstays reduced to half-remembered names in a hotel ledger. In this land of summer possibility, the young man adopts a new name and identity and takes up with an actress and a seedy, charismatic doctor from an old Haute Savoie family. Together they amble through hotel and beach club communities causing minor scandals.

The climax comes with possibly the most memorable, and certainly the most exuberant, set piece in Modiano’s oeuvre: the Houligant Cup, a “concours d’elegance,” on which seemingly all the characters’ hopes and dreams are momentarily riding, a brief and wondrous absurdity that perfectly captures the strange summer atmosphere in Annecy, distorted by time and memory. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads editor-in-chief

Erin Somers, Stay Up with Hugo Best

A sometimes-overlooked quality of summer is that it’s the favorite season of ostentatious displays of wealth. We might know that extremely rich people are off somewhere being extremely rich in winter, too (skiing? Drinking port by the fire?), but in the summer they’re all so obviously summering and spending time on their grounds. So in case you need a reminder of the dissatisfaction and melancholy that can accompany even the fanciest in-ground pools, I recommend Erin Somers’ excellent debut. Even if you’re not in the market for schadenfreude (ugh, fine), the (sharp, wrenching) novel, which tells the story of a young comedy writer’s fraught Memorial Day weekend at the country house of a late-night legend, makes for excellent summer reading. –JG

Marguerite Duras, The Lover

A glorious, slender novel about a forbidden love affair. May or may not inspire you to purchase an extravagant summer hat. –ET

Jennifer Egan, The Keep

Egan’s best novel (that’s right, I said it) has everything I want in a summer read: a mystery, a medieval castle, a tinge of menace, a twang of metafiction, and atmosphere for days. Those who first encountered her with Good Squad and never bothered to read backward: you’re in for a treat. –ET

Raven Leilani, Luster

This was the best book I read in summer 2020, the summer of Covid and protest. But it also evokes all of the best qualities of the season: a sense of thrill and danger, a sparkling irreverence, freedom and play. Also… it’s kinda hot. In that gross, sticky way, sure, but also in the other way. What more could you ask for? –ET

Max Frisch, translated by Geoffrey Skelton, Montauk

Did I purchase Montauk, Max Frisch’s very autobiographical 1975 novel, from a Hamptons bookshop last summer because I loved the cover art? Yes! But then I read it and was very glad I took the plunge. The story is about a writer (Frisch, it is very obvious) who spends a summer weekend in Montauk with a younger woman with whom he is having a short love affair. As the hours pass, he remembers things about his life and writes them down. He observes things and writes them down.

The novel is kind of about nothing, in this way, but it is also possibly about everything in this way. Mostly, for me, it seemed to capture the kind of narration we (or at least I) do in our heads when we’re experiencing something ordinary but are wondering if it is secretly profound. –OR

Hiroko Oyamada, translated by David Boyd, The Hole

This was the book that my two friends were each reading on the beach when I was reading Montauk (see above), and their descriptions were enough to make me seek it out. Asa is a young, newly married woman who moves with her husband to the country, near where his parents live. This is all during an extremely hot and unpleasant summer, and she, bored and restless, spends her time half-exploring, half-wandering around, until an encounter with a strange animal leads her to fall into a giant hole, a hole that has been waiting specifically for her. –OR

Karen Russell, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves

Karen Russell stories always make me think of the summer months. Probably because they all take place in the warm swamp of the Florida Everglades, and the environment breathes down your neck the whole time. Alligators, crab shells, and houseboats abound! The boundaries of reality get quite hazy in these stories in a way that echoes the way summer can feel ripe with unburdened possibility. One wild story in particular is set in a sleepaway camp for disordered dreamers, and is exactly the kind of story you want to tell while sitting around a campfire. –KY

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

It’s kind of boring to include The Great Gatsby on lists like this, but in this case I can’t help myself, because it really is the perfect summer novel—it’s short, it’s tragic, it’s beautifully written without being dense, it’s about wealth and striving and reinvention, and of course, it roughly spans a single summer. Then there’s the swimming pool… a true American summer novel. –ET

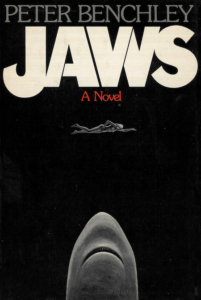

Peter Benchley, Jaws

A very good reason (or two) to stay on the beach. –ET