Our Favorite Literary Hub Stories from 2018

From William Faulkner to Cave Exploration, and Much Much More

It’s hard to find anyone who will speak of 2018 as a great year—for people, politics, the planet—so we’re not exactly sad to see it go. We are glad, however, for some of the wonderful stories we had a chance to work on this year, and have listed some small fraction of them below.

Aaron Robertson, assistant editor

Aaron Robertson, assistant editor

*

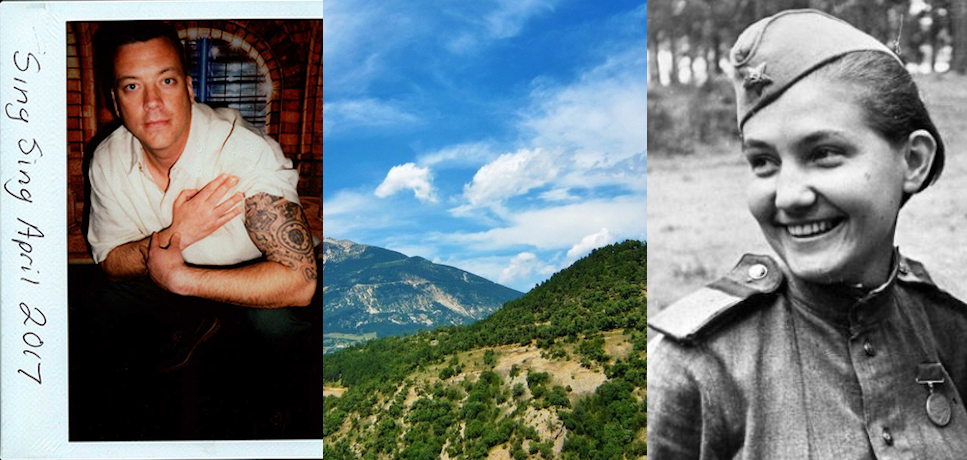

“How John J. Lennon Became a Prison Journalist—From the Inside”

by Daniel A. Gross

Daniel Gross’s profile of John J. Lennon, a one-time drug dealer and convicted murderer turned journalist who is still serving time in a maximum security prison in New York, is a remarkable story, if not of easy redemption, then at least of hope for better things to come. A close family member of mine was imprisoned for many years, and one of the remarkable things about his “rehabilitation” was how much time he devoted to reading, writing and mentoring his fellow inmates. Similarly, Lennon shows that bars can’t always restrict the vitality of mind and spirit. He has no Internet access, limited contacts on the outside, and his cell doesn’t even have a chair. Despite all that, he’s published reported pieces for The Atlantic, The Marshall Project and other outlets. It isn’t always clear what the path to absolution looks like, put perhaps Lennon’s life is a model.

*

“The Other South of France: My Year(s) in the Pyrenees”

by Laurence de Looze

Reading Laurence de Looze’s long meditation on provincial life in Roussillon, in the south of France, was to visit a place that even many Parisians don’t know is there, to taste the wine sold in the local cave coopérative, and to sit beside the author’s friend, Michel Bardagué, the “philosopher of the fields”, a villager who seems to understand more about the world than most simply because the land he has lived and worked on for much of his life tells him all he needs to know. This is a story about many things, but friendship most of all. Soon I’ll have to buy my ticket to the eastern Pyrenees.

*

“I Was Almost Svetlana Alexievich’s Translator”

by Laura Esther Wolfson

Translators—the “unsung, silent heroes of literature,” some have said. Laura Esther Wolfson sings her own mournful song in her non-fiction collection, For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors. Wolfson’s essay on Russian literature and culture, illness and her often unromantic career as a translator (through no fault of her own, as we learn) somehow manages to be a reflection on a writer’s sometimes bitter relationship with language and her craft, and a wonderful commentary on Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich’s work. I still think of Wolfson’s bittersweet line on fame: “For there must be few things more miraculous to witness at close range or to live through than that instant when the light falls on something long swathed in shadow, washing it golden and bestowing worldly sense upon years of toil and obscurity.”

![]()

Emily Temple, senior editor

Emily Temple, senior editor

*

“20 Debut Works of Fiction by Women Over 40”

by Jenny Bhatt

Earlier this year, Jenny Bhatt called for more lists celebrating women writers above 40—and started a massive discussion on Twitter. We asked her to turn the idea into a piece for Literary Hub, and I’m so glad she did—it’s a list that’s both pleasurable to read and actually useful, both on a book-by-book basis (there are some great ones on there) and on an inspirational one. More lists like these!

*

“Let’s Talk About the Fantasy of the Writer’s Lifestyle”

by Rosalie Knecht

In this essay, Knecht not only nails what I love so much about the Anthropologie catalog but also the damage the romantic idea of the writer can do. The fantasy “leaves us with no model to follow when we try to integrate art-making with functional lives,” she writes. “That period when a person could make a living writing fiction for periodicals was a blip, and it’s over; we’ve long since returned to the baseline, which is that the vast majority of fiction is written around and beside a whole lot of other work, and it’s the other work that pays the rent. As such, there is no writer’s lifestyle; your lifestyle is determined by what that other work is.” This essay helps me love the practical magic of writing, which is a good thing, because that’s all there is.

*

“Color or Fruit? On the Unlikely Etymology of ‘Orange’”

by David Scott Kastan with Stephen Farthing

Over the course of my life to this moment, I have spent more time than I care to admit thinking about the word “orange.” Why does nothing rhyme with orange? How did that happen? But as this essay taught me—it’s not only that nothing rhymes with orange. Orange is an outlier, a one-of-a-kind. It’s “the only basic color word for which no other word exists in English. There is only orange, and the name comes from the fruit. Tangerine doesn’t really count. Its name also comes from a fruit, a variety of the orange, but it wasn’t until 1899 that “tangerine” appears in print as the name of a color—and it isn’t clear why we require a new word for it. This seems no less true for persimmon and for pumpkin. There is just orange. But there was no orange, at least before oranges came to Europe.” Intrigued? I know, I was too. So for the nerdiest deep-dive into the history of a single word, look no further.

![]()

Jonny Diamond, editor-in-chief

*

“Whose Story (and Country) Is This?”

by Rebecca Solnit

It is very hard to look back at a year’s worth of Rebecca Solnit’s writing at Lit Hub and choose just one piece. From the dark banalities of Donald Trump’s administration to this country’s epochal shifts in reckoning with patriarchal power, Solnit is unique in her ability to articulate and interrogate the most urgent issues of the moment. Solnit herself sums up, perhaps, in the essay above, what it is that animates much of writing:

The common denominator of so many of the strange and troubling cultural narratives coming our way is a set of assumptions about who matters, whose story it is, who deserves the pity and the treats and the presumptions of innocence, the kid gloves and the red carpet, and ultimately the kingdom, the power, and the glory. You already know who.

*

“All About My Mother: On Love, Rage, and Family”

by Brandon Taylor

It is hard to write about one’s mother, one’s family, one’s childhood, not solely because the memories might be traumatic or painful, but because it is a form particularly vulnerable to cliché—even the best writers are susceptible to lenses of nostalgia that tint variously toward the rosy or the grim. Brandon Taylor, who is, indeed, one of our best writers, avoids the aforementioned traps in this powerful, finely wrought account—part eulogy, part testimony—of life with his mother. There is forgiveness here, without elision, and honesty without indictment.

*

“Inside the Slow-Motion Disaster on the Southern Border”

by Laura Tillman

This past summer we sent Mexico City-based writer Laura Tillman to the US-Mexico border to seek first-hand accounts of those effected by the ongoing separation of families seeking asylum. Tillman found there stories of mothers, fathers, activists, lawyers, and more, all trying to cope with—as this feature’s headline suggests—a crisis that just doesn’t seem to have an end. With a nod to the reporting-by-accumulation of Svetlana Alexievich, Tillman’s story reminds us of the importance of direct testimony.

![]()

Corinne Segal, senior editor

Corinne Segal, senior editor

*

“A Year of Writing Anonymously”

by Stacey D’Erasmo

In “A Year of Writing Anonymously,” D’Erasmo asks what happens to our writing when we hold our own egos more lightly. D’Erasmo wrote an anonymous column for a year as the “Magpie,” a character that found something fascinating everywhere she looked. “I was astonished by how abundant and interesting the world became,” she writes.

Why would that be the case? D’Erasmo dives into the effects of external pressures in the publishing industry that cause women and queer people to self-censor for fear that their inner lives are less interesting, palatable, and “literary” than their counterparts, and the freeing effects of anonymity. But she also turns that analysis on herself, and the result is insightful, fascinating, and a lesson for any writer struggling to stay awake to the present moment.

*

“My Year of Smoke: Finding Echoes of Frankenstein in the California Fires”

by Joy Lanzendorfer

During a brutal season of California fires, Joy Lanzendorfer fled north to Oregon with her family. She recalls the year, almost two centuries ago, that the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia muted summer around the world and Shelley escaped to Switzerland, where she began writing one of the classics of English literature. It’s a compelling history with implications for the current reality of climate change.

*

“William Faulkner Was Really Bad at Being a Postman”

by Emily Temple

It turns out William Faulkner was a terrible postman. Who knew? Here, Emily Temple walks us through the excruciating incompetence of Faulkner the postman and his various mail-related failures. It’s good to know that sometimes the greats of American literature were bad at stuff.

![]()

Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

*

“10 Contemporary Classics of Children’s Literature by Authors & Illustrators of Color”

by Eugenia Vela

I love children’s books. I spend an absurd amount of time thinking about them, looking at what we’re passing down to the next generation. In this piece, BookPeople’s Eugenia Vela recommends children’s classics you might not have heard of. (I hadn’t.) Some of these characters dig into family folktales. Some of them deal with immigration. Some of them just love splashing in rain puddles. It’s a wonderful, well-rounded list that speaks to the importance of seeing yourself in literature, of having characters that look and speak like you do.

*

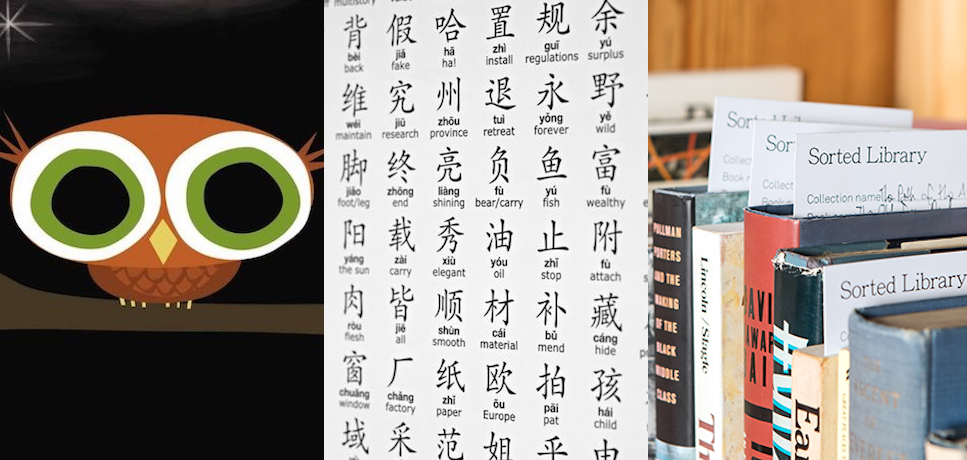

“On Falling In Love With the Language I’ve Spoken My Entire Life”

by Lucy Tan

This is a beautiful essay about how hard it is to put things into words sometimes. Especially when those words have to bridge a cultural gap, especially when you live between languages. Lucy Tan talks about pushing away from Chinese, thinking that this separation was necessary to become a writer. She speaks very honestly about her family, discovering Eileen Chang, and the small gestures that say I love you. I don’t even have the words to explain how amazing this piece is; just read it.

*

“Visiting an Experimental, Do-It-Yourself Library in Brooklyn”

by Phillip Pantuso

Apparently there is an experimental library in Brooklyn. (Where else?) In this library, visitors are invited to create their own collections surrounding any theme they so choose (favorites include “Books Sometimes Used To Justify Shitty Behavior” and “The Fictional Life + Death of a White Man”). Phillip Pantuso gets into the joys of browsing and discovery. He’ll remind you what it was like to wander into a library and just fall down the rabbit hole.

![]()

Emily Firetog, deputy editor

Emily Firetog, deputy editor

*

“The Transcendent Humanity of the Worst Cruise I Have Ever Taken”

by Ramona Ausubel

Ramona Ausubel’s essay from early March recounts a miserable (and hysterical) 36-hour ferryboat ride across the Black Sea, where an entire boat full of seasick Ukrainians and Ausubel and her husband try not to die. There are some events that are so awful and bizarre that fiction won’t do them justice, and thank god for that.

*

“A Literal Hell Constructed For Children: Dina Nayeri on Family Separation”

by Dina Nayeri

While having a young child is not a prerequisite to thinking that the act of separating children from their parents at the border is a horrific crime, seeing children the same age as your own is a particularly mind-numbing thing, becoming an attack on your own sense of reality. In her essay, Dina Nayeri introduces readers to her daughter Elena and her world, her struggles to sleep alone, her idiosyncratic language, and its steadfast rules (“The steps of girlhood development go: baby, little girl, big girl, ballerina. Ballerinas are tall women who protect her, like fairy godmothers (they include mommy, nursery workers, a certain aunt) but aren’t the severe grownups out in the scary world, which she calls ‘America’ because I travel there for work.”) And it is here that Nayeri begins to associate Elena with the children stuck in border cages. “I wonder how long it would take for a stranger to decipher each unique toddler tongue. What if the stranger isn’t allowed even to offer a cuddle or a kiss?” She remembers her own childhood escaping Iran, then visiting refugee camps in Greece, in the end trying to decipher what has happened to America’s inner world. It is a devastating, beautiful piece.

*

“The Debut Novelist’s Guide to Battling Imposter Syndrome”

by Sharlene Teo

Sharlene Teo’s debut novel Ponti was published this year to rave reviews, yet her feelings of insecurity and imposter syndrome continued well after publication. Personified here through short reflections (“My imposter syndrome loves to come out to literary events. She watches other writers who have the self-control to stop at half a glass of lukewarm Chardonnay. Wonders how they do it, manage their anxiety so elegantly without being tempted by free wine?”) Teo is able to pinpoint the ways in which we sabotage ourselves with beautiful clarity, humor, and heartfelt honesty.

![]()

Miriam Kumaradoss, editorial fellow

Miriam Kumaradoss, editorial fellow

*

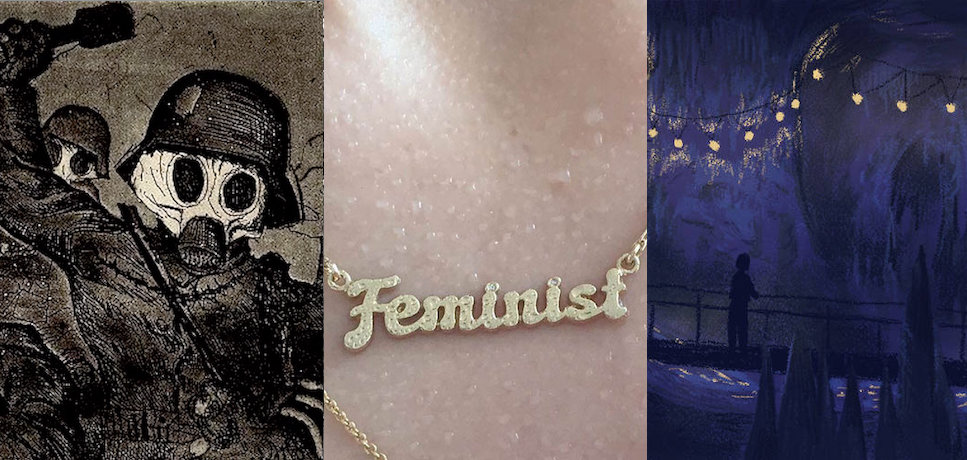

“How Horror Changed After WWI”

by W. Scott Poole

Tracing the human fascination with death from its primordial origins to the point where real-life carnage warped it into something more horrific than ever before, this piece is a must-read for anybody with an interest in horror (whether in film, fiction, or other media). W. Scott Poole draws from several sources and disciplines to lay out a history of horror that begins in a manner that’s almost playful (unsurprisingly, the first goths—or those who we would today refer to as goths—were the wealthy classes of the 18th century play-acting at being spooky) but goes on to describe the ways that the all-too-real terrors and tragedy of World War I changed humanity’s treatment of death. It’s not a reassuring year-end read, but it does seem important (especially at the end of a year like 2018) to contemplate how large-scale violence can bleed into the psyche of an entire generation, unsettling humanity in unforeseen and far-reaching ways.

*

“How Do We Move Beyond Commodified Feminism?”

by Charlotte Shane

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, conversations about feminism have blown up in the mainstream, but are they always the conversations we ought to be having? Like Charlotte Shane, I identify as a feminist and always will, but was blown away by how she interrogates the commodification of feminism and presents an argument for intersectionality, the fact that misogyny is tangled up with several other equally pervasive evils, and that simplistic gender dynamics cannot be the only lens through which we view and fight for social justice. Amidst the chaos of 2018, this piece stood out to me as a call to be wary of intellectual laziness and to not settle for easy answers. As Charlotte Shane so brilliantly puts it: ” When feminism is treated as if it can respond solely to oppressions that move neatly from men to women—with no complicating factors or contextual ambiguity—it becomes the agent of our enemies.”

*

“How to Read Caves”

by Susan Harlan

I’ve probably written this in another list of recommendations someplace, but my favorite kind of nonfiction braids together disciplines (especially when bringing together science and art), lyrical sentences, and striking imagery. How To Read Caves is a perfect example of just that. It’s a cross-disciplinary meditation on caves—in literature; as metaphorical and metaphysical sites; as geographical formations; as historically significant places—tied together by Susan Harlan’s vivid, often eerie narration of a tour of Tuckaleechee Caverns in Tennessee. Several of these images and ideas will follow me into 2019 and well beyond, and I’ll be better off for them. Read the essay, peer into the dark, contemplate the cave; chances are, you’ll be better off too.

![]()

Jessie Gaynor, social media editor

Jessie Gaynor, social media editor

*

“What if I’m Just a Minor Writer?”

by Karl Taro Greenfield

Karl Taro Greenfield’s essay on pursuing (and likely falling short of) literary immortality was such a thoughtful reflection on the ways in which we measure success as writers, and what it takes to keep writing even as the dream of “greatness” shifts to accommodate reality. Greenfield has made his living as a writer for 30 years, and published nine books, yet he writes of his literary career, “I didn’t become what I dreamed.” I love this piece because it’s a realist’s twist on “work hard and all your dreams will come true.” Work hard, and you’ll continue to work.

*

“Having No Time Is the Best Time to Get Writing Done”

by Jessie Greengrass

Jessie Greengrass’ piece about the value of having to fit writing into the slivers of free time in a busy day resonated strongly with me, a person whose response to vast swaths of unscheduled time is to burn through the hours like so many Lady Fair cigarettes. “This thought then, now, still: that it is a lack in me which made those years not transformative, but lost,” Greengrass writes, acknowledging the fear that coexists with the peace she feels now. The writing in the piece is so sharp (painfully so, at times) that it’s absolutely worth a read even if you’re not desperately seeking validation for your misspent mid-youth.

*

“Not Just a German Word: A Brief History of Schadenfreude”

by Tiffany Watt Smith

“This is a confession. I love daytime TV. I smoke, even though I officially gave up years ago. I’m often late, and usually lie about why. And sometimes I feel good when others feel bad.” Tiffany Watt Smith’s exploration of Schadenfreude touched on so many of my interests (synchronized swimming fails! Secret smoking! Malicious delights!) that I would suspect her of pandering if she knew me at all.

![]()

Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

*

“Adventures in Insomnia”

by Marina Benjamin

In this eerie, fascinating, and frequently very funny, excerpt from Insomnia, Marina Benjamin considers the nature of that most accursed of nighttime maladies, the limitations of traditionally prescribed counter-measures, Nabokov’s prophetic dream journal, the shared dream landscapes of people living under oppression, and more. “I could murder some sleep. Even at the price of reckoning with my soul. Especially at that price, in fact, since everybody carries a part of the night within them, a small piece of impenetrable, unknowing darkness…”

*

“Some Like It Dark: Terror in Translation”

by Heather Cleary

To usher in the Halloween season, acclaimed translator Heather Cleary recommended four short, cerebral, and thoroughly haunting works from recent years. A moody Taiga-set noir, a nightmarish vision of East Germany, a macabrely poetic tale set in a 1960s Brazilian orphanage, and a Sade/Poe-inspired collection of novella are all beautifully and thoughtfully illuminated by Cleary, whose own latest translation (of Roque Larraquy’s Comemadre) was longlisted for the for the 2018 National Book Award for Translated Literature.

*

“Kevin Williamson, Transphobia and the Myth of Ideological Diversity”

by Gabrielle Bellot

A brilliant, scorching piece by Gabrielle Bellot on the naked transphobia of Kevin Williamson (recently hired, and even more recently fired, by the Atlantic) and the cynical attempts by certain media outlets to win-back right-wing readers by hiring Never-Trump conservatives as pundits, regardless of how regressive and offensive their past writings have been, at the expense of any meaningful progressive or left-wing representation. “Unfortunately, ‘ideological diversity’ often really means exploring the far right and ignoring the far left. Why hire a radical queer writer, when you could hire a transphobe who believes that accepting the scientific and social reality of trans people means regressing to “very primitive understanding of reality?”

![]()

Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads managing editor

Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads managing editor

*

“Isidore Zimmerman: The Man the System Couldn’t Break”

by Nathan Ward

There are some life stories that are just too crazy, too powerful to make up. Here, Nathan Ward tells the story of Isidore “Izzy” Zimmerman, a young New Yorker pinched on a murder rap and scheduled to be executed at Sing Sing, only to be granted last minute clemency and sentenced instead to life in prison. Zimmerman was innocent of the charges against him, but he served almost 25 years anyway and endured brutal beatings and solitary confinement, but they couldn’t break his spirit. After he was finally exonerated, Zimmerman wrote a book and fought for the right to sue the state of New York. Ward was working at a paperback shop when he met Zimmerman, and looking back on their brief acquaintance he remembers a man who wouldn’t let the system take him down, and who wanted to get rich so that he could take all his friends out for Chinese food.

*

“A Preacher, a Scam, and a Massacre in Brooklyn”

by Sarah Weinman

Sarah Weinman’s article, “A Preacher, a Scam, and a Massacre in Brooklyn” is everything I want from a true crime investigation: taking a piece of recent history, shining a line on it, and in the process fundamentally altering how I see a familiar piece of the city and its history. In this case, Weinman looks at a townhouse in Crown Heights and tells the story of a charismatic, self-styled ‘preacher’ who for years ran a donations scam out of it, scooping up vulnerable women and sending them out dressed as nuns to collect donations. Then the women began to disappear, and the real secrets of the ‘church’ were found out. This story comes from the 1970s, but is continuing to unfold today. I pass by the townhouse regularly, and I’m sure from now on a deep shudder is going to run down my spine every time I do.

*

“Towards a History of Mediterranean Noir”

by Sandro Ferri

This essay captures in a few thousand words all the reasons why I love crime fiction. Beginning with the murder of Abel by his brother Cain and the epic poems and tragedies of ancient Greece, then moving to the modern era where Camus gave way to Manchette, Jean-Claude Izzo, and Yasmina Khadra, Ferri draws a provocative and insightful line, defining a literature that shares certain attributes—an “inquisitive” tone, a keen sense of fatalism and irony, the defense of society’s most vulnerable, and an appreciation of grilled fish and hearty drink—that strike a chord with so many of us. I’ve always read Mediterranean Noir, always will, but it was a special treat to find the books and cities that have meant so much to me tied together this way. And it doesn’t hurt that the essay’s author is the publisher (Europa) who helped to make sure so many of these works could be read and appreciated in the U.S.

![]()

Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor

Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor

*

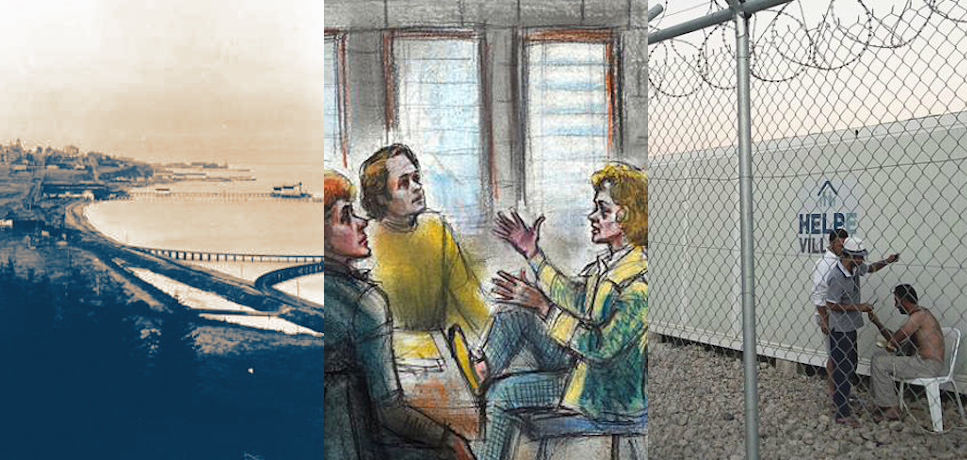

“The Cheerful Sinners of The Pacific Northwest’s Wildest City,”

by Katrina Carrasco

In this rollicking good read, Katrina Carrasco takes us in the wild and woolly past of historic Port Townsend, full of drunkards, sailors, smugglers, and the inevitable roster of corrupt customs officials that allowed for all that smuggling. I love this essay because it reminds us that the misery of the criminal underworld could often go hand in hand with an anarchic freedom, and I’m fairly certain that the turn-of-the-century denizens of Old Port Townsend were having a much better time than the residents of, say, Salt Lake City, or Boston, or the entire Midwest.

*

“The Strange Case of Jean Harris”

by Gina Wohlsdorf

This bizarre true crime story is a great example of fact as stranger than fiction. In 1980, schoolmistress Jean Harris killed her lover for a whole set of understandable reasons: “Jean Harris was in a seriously embattled position at work, she was addicted to prescription meth, and her boyfriend of a decade and a half was slo-mo dumping her for a twinkie he had on the side.” Then, she went ahead and told the court she shot him four times by accident while trying to kill herself. Crime writer Gina Wohlsdorf came across the case when she was working at an archive helping to catalogue the courtroom sketches of Ida Libby Dengrove, one of Harris’ (only) friends.

*

“Fighting Injustice with Fiction”

by Ausma Zehanat Khan

International human rights lawyer and prolific author of genre fiction Ausma Zehanat Khan wears many hats, yet her work, no matter the medium, always emphasizes the fight against injustice that has shaped Khan’s entire life. Here, Khan remembers her first experiences with activism, and looks at the power of fiction to give voice to those society would prefer to ignore.

![]()

John Freeman, executive editor

John Freeman, executive editor

Wilder Things: Modern Life Among the Foxes and Coyotes

by Aminatta Forna

In the city of London, you’re never far from a fox. What does that mean, Aminatta Forna want to know, and to those who live in cities she asks: what is our responsibility to creatures who live among us? This is a beautiful, thoughtful essay about sharing. Its pleasures and the moral imperatives. Moving from DC, where she lives now, to suburban Massachusetts and elsewhere, Forna looks at the wild animals that live among humans in plain sight and thinks about the idea of dominion and the damage its done. She describes the resilience of the American coyote and mourns the knee-jerk fevers of deer population conversation in the DC suburbs. I’ve never read an essay where the animals in it are treated as equally valid living organisms. Forna’s gorgeously intelligent novel of this year, Happiness, will take years to absorb, its portrait of human and animal cohabitation is that radical. This essay is that book’s confident handmaiden: please read it.

*

Fascism is Not an Idea to Be Debated, It’s a Set of Actions to Fight

by Aleksandar Hemon

During the 2016 campaign and in the early years of the Trump administration, no one saw the dangers of Trumpism quite so lucidly as Aleksandar Hemon. The Sarajevo-born writer watched a home-grown nationalism, possessed by a very few, tear his former country apart in the 1980s and early 1990s. That experience turned Hemon’s life into a before and after period, becoming the rupture through which he sees the world. He doesn’t simply wag a finger. One of the great things about Hemon’s essay writing style is its loose story-telling manner, and how he deploys this in a time of catastrophe. Whereas most essayists in political sphere makes arguments, Hemon simply tells better stories. Each one of his essays on the march of Trumpism, and there’s nearly enough for a book now, clarifies a different step in nationalism’s logic, doing so by wrapping that vision around a miniature fable. Hemon’s description of the way political rhetoric normalizes violence on this site last year, for example, was terrifying, because Hemon showed how it was operating within himself. How he’d nearly become a neighborhood brawler in Chicago. This fall, two years in, the energy is different: almost a fatigue. There was even an instinct to debate the ideas that had clearly become if not fascistic, then fascism-friendly, which to Hemon is yet another step in the normalization of fascism, American style. To that Hemon tells this poignant and terrible story, about watching a friend descend into the hatreds of fascism in Bosnia in the early 1990s. Hemon remembers his desire to debate the seed of fascism in his friend, to ignore it, and then, finally, to cling to the friendship, even when the ideas his friend possessed were hateful and led to murder. Possibly some all but committed by his friend. I don’t always agree with this essay’s starkness on the situation here, but I admire it for making me ask myself the questions I want to shy away from: as in, when do you have to admit the time for debate is over, has been for some time?

*

Windows to the World: At WS Merwin’s Old French Farmhouse

by Michael Wiegers

For the past seventy years—and pause to respect the scale of that number, the hours and minutes, the train rides and many sleeps embedded there, the loves and people lost—the poet W.S. Merwin has retreated to a farmhouse in a small French village to restore in himself the capacity to live on the land. In our era of lifestyle journalism, this sounds like an annoying instagram post. In Merwin’s time, though, buying a dilapidated farmhouse without a bathroom for a few hundred dollars after a devastating global war and making it home was a statement. In this moving piece of biographical writing, Copper Canyon editor Michael Wiegers chronicles how Merwin slowly adjusted to life alone in a hard place with donkeys and visiting lizards. He also shows how resurrecting the house—which had plunging views but was barely livable—changed and deepened Merwin’s poetry. It’s hard to appreciate now just what a force Merwin has been in American letters. How crucial The Lice, his 1967 Pulitzer Prize winning book, was to clarifying the rot at the heart of American empire. How much his translations opened a door into the world outside North America. What his respect for the natural world meant to people like Barry Lopez, who has said Merwin made him a writer more than any other. No one alive moves a poem quite like him, and Wiegers makes clear that Merwin learned that freedom over a farmhouse bench in a cold stone room.