Visiting an Experimental, Do-It-Yourself Library in Brooklyn

Dev Aujla's Sorted Library Wants to Celebrate Nonlinear Thinking

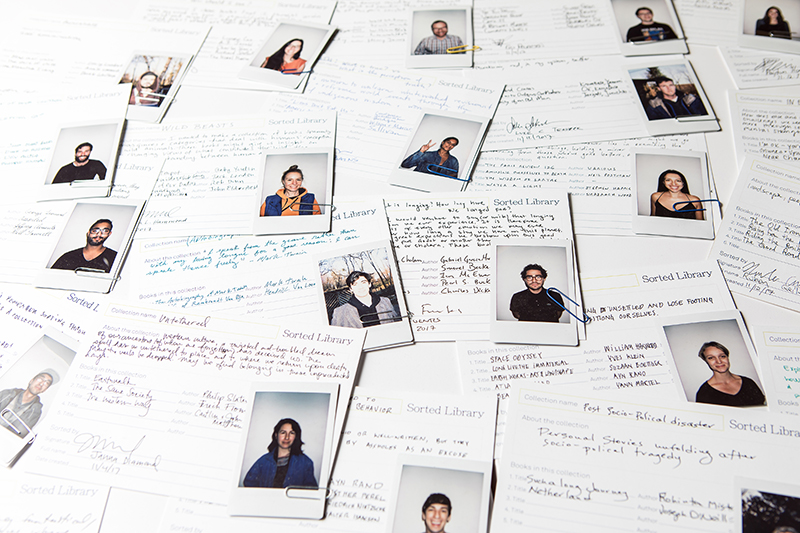

In a windowless room tucked into a ground-floor corner of a co-working and incubator space in DUMBO, Brooklyn is the Sorted Library. You would never find it, if you weren’t looking for it. It’s less a library in the traditional sense (you can’t borrow the books), and more a reading room-cum-social space for those who find themselves there (by invitation only, at this point). From more than 3,000 volumes spanning all categories, visitors are invited to create a miniature library around a topic or theme of their choosing by selecting three to five books and filling out a card to explain how each title fits into their collection. Its founder, Dev Aujla, calls it a “cultural organization that is rethinking the modern library experience.”

The primary goal of the Sorted Library is to encourage a serendipitous discovery process by, counterintuitively, limiting the amount of material available for discovery: in offering visitors fewer choices, the library forces them to be flexible. You can see what the results look like on the Sorted Library’s Instagram. The collections are by turns profound (“The Fictional Life + Death of a White Man”), abstract (“Fuzzy”), whimsical (“Books My Mom Teaches to High Schoolers”), instructive (“Building With Intent”), and wryly humorous (“Books Sometimes Used to Justify Shitty Behavior”).

Aujla, a writer and entrepreneur originally from Victoria, British Columbia, wants to promote “non-linear thinking,” a heuristic he finds increasingly important in our algorithmically determined world. “There’s something that happens differently when you look into poetry, architecture, art, history, and you’re constrained [by] the amount of information you have,” he told me. “We always have access to everything, but this isn’t the New York Public Library—I can’t just get the book on the suburbs I’m looking for. There is no book on the suburbs here! So you’re forced to dig around the architecture section, or find something in American politics, and create a collection around an idea or impression you have. I’m advocating for a different, more creative way of thinking.”

Sorted Library co-founder Dev Aujla. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

Sorted Library co-founder Dev Aujla. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

The current iteration of the library is a scale model of what Aujla hopes will one day be a much larger institution featuring perhaps a dozen reading rooms comprised of the personal libraries of interesting thinkers, famous or not. Visitors would then cull their own collections from these curated rooms, in effect creating a matrix of organizations—theoretical libraries out of the actual one. “You can create a collection in Pessoa’s library, and then take the same question to Audre Lorde’s library, or Satyajit Ray’s,” he explains. “I just want to know what happens when you go with the same question to a different collection. I find that so poetic.”

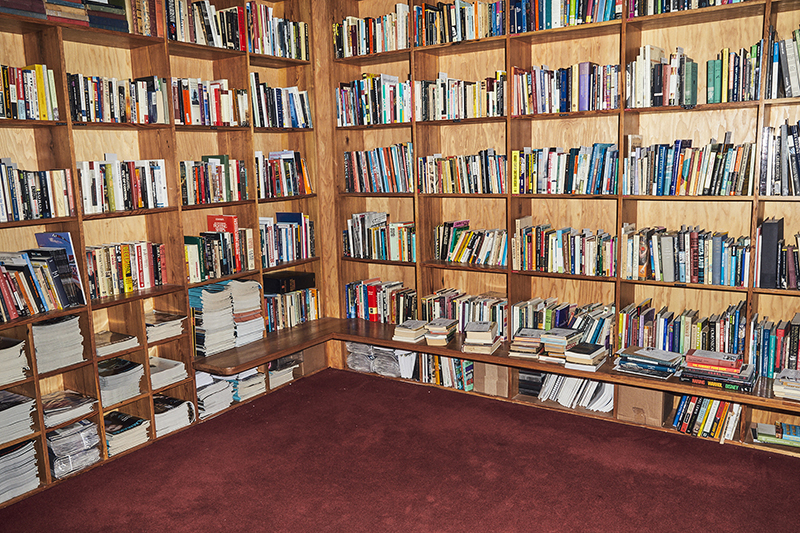

Aujla’s vague ambitions of starting a library project were born in 2016, when he started going daily to the Community Bookstore in Cobble Hill, which was then closing down, and choosing books to take home. Eventually he struck a deal with the owner, John Scioli, and ended up with 3,000 books in his one-bedroom apartment. Their weight caused the floor to begin sinking until he moved them into a back-corner chamber with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and plush garnet carpeting in the Made in NY Media Center by IFP, a co-working space and exhibition venue, where they still reside. The original 3,000 titles have been supplemented by purchases from occasional book-buying expeditions to places like Rodger’s Book Barn, a literal barn full of inexpensive used books in Hillsdale, NY. Small donations from friends, including of the space itself, have helped bring the project to life, though Aujla has mostly self-funded it.

The Sorted Library’s space at Made in NY Media Center. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

The Sorted Library’s space at Made in NY Media Center. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

Aujla is a thoughtful and generous interlocutor; his earnestness is winning, and at least partly to credit for the number of creative librarians and bibliophiles he’s brought into the braintrust of this project. Heather Topcik, the director of the Bard Graduate Library and a board member of the Art Libraries Society of North America, New York chapter, met Aujla through a mutual friend. “I’m really drawn to nontraditional library spaces and projects,” she told me one afternoon in her office.

Topcik draws a distinction between those types of spaces and a research library, like Bard’s, which is set up to foster a linear process of discovery: you come in with a research question, burrowing through bibliographies and citations to capture information, which ends in a scholarly written work or a book that goes back into the library, to be discovered by the next person pursuing the same line of inquiry.

“I see these other, more creative library projects as, in some ways, meditations on collections and the physical object of the book,” she says. “In Dev’s case, it’s not the physical object as first edition—there’s nothing particularly precious about the books themselves; they’re mostly paperbacks, secondhand, in decent condition—but it’s about the idea of a library and what that can mean. I think there’s some nostalgia there, because people don’t use libraries, unless you’re a student. That has been lost a little bit.”

Whether or not you think the Sorted Library is even a library depends entirely upon the definition of “library,” a surprisingly fuzzy ontological category the more you focus in on it. Is a library simply a collection of books, organized? Do the books need to be available for lending? How objective does the classification need to be? How do we define objective, and for whom?

“Browsing is a real way of discovery. Even if you have multiple access points in an online search—which is great!—it’s not the same experience as looking at a book on a shelf, and then looking at the book next to it.”

Topcik sees the Sorted Library as part of a crop of newer, idiosyncratic book-spaces that blur the concept of a library. She specifically mentions the Reanimation Library, in Red Hook, an independent library of obscure and obsolete books—“relics of the rapidly receding 20th century”—chosen and repurposed as art objects for the images they contain, and the Sitterwerk Art Library, in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in which books do not have a fixed location but are instead catalogued by a robot.

At Sitterwerk, the books can, in principle, be placed anywhere on the shelves; at regular intervals, identification tags affixed to the books are scanned by an automatic mechanism that creates a continuously updating inventory of the current location of every book. The ordering of the books is adapted to the use patterns of individual visitors to the library, which fosters “the principle of serendipity as a novel search option,” as the library’s website so artfully puts it. In addition to searching by author, keyword, or subject, visitors can also query the digital catalog for a book’s “context”—which books are nearby it at the moment, or which books it has previously been grouped with. (Aujla visited Sitterwerk early this year for inspiration.)

Digital classification has abetted the evolution of the library. In the past, a librarian would be tasked with deciding whether to shelve a book about art nouveau metalwork in the art nouveau section or the metalwork section. Now, given that most people will first encounter the book via an online search, it can functionally exist in both places. But the act of browsing and its concomitant serendipitousness are less available.

“That’s not just nostalgia,” Topcik says. “Browsing is a real way of discovery. Even if you have multiple access points in an online search—which is great!—it’s not the same experience as looking at a book on a shelf, and then looking at the book next to it.”

Collection cards at the Sorted Library. Photo by Shella Barabad.

Collection cards at the Sorted Library. Photo by Shella Barabad.

And browsing within someone else’s personal collection, or building your own, is a way to root around in the paraphernalia of identity. I have gotten rid of hundreds of books throughout my life, but the ones I drag from apartment to apartment I’ve held onto because, at some point, I decided they said something about me. Even if I’m not always sure what that is, it’s reassuring to browse my shelves and connect the books there to specific memories, people, phases: Juan Villoro’s The Reef also tells the story of a trip I took to Mexico; Elena Ferrante of an ill-fated move to Italy; Infinite Jest of an uncertain postgraduate summer when a friend and I started a book club that was at least as much about meeting for beers as it was about books.

“Artworks, like libraries, contain the traces of personalities; of curiosity and inquiry, emotion and action; and sitting with collections encourages us to rethink what we know,” Nicholas Andre Sung, an art director and friend of Aujla’s, told me. “Collections remind us how much more is out there, how many more ways there are to know, and how much further each of us can go to explore, interpret, and share.”

Each collection at the Sorted Library is the unmistakable product of a single mind, but in sum they begin to comprise something like a spectrum of human curiosity and thought, at least for the type of human who comes to an arcane library project in Brooklyn.

The Sorted Library venerates the idea that self-knowledge can be a platform for connection with others, too. Aujla has brought in a diverse range of visitors, including an architect, a dancer, a biologist, a geologist, an artist, and an English teacher. Some are Aujla’s friends, people he admires and whose collections he’s curious to see, but most visitors have come after hearing about the library via word-of-mouth, discovering it on Instagram, or having been invited to one of a handful of socials Aujla has convened with other librarians. “I’m not trying to make it this elite thing,” he says. “Anybody can come; I’m just slowly stepping into that.”

On her visits, Topcik has been enamored with the Sorted Library’s social possibilities, in contrast to the often solitary experience of most library visits. Soon Aujla plans to open up the library to the public, probably one Sunday per month to start. He’s found that the conversations that ensue have been deeply rewarding. “Ideas, books, the work that people are doing in their personal lives, the questions they bring to the space—these are all on the table right away,” he said. “It’s a really beautiful way to spend time with somebody.”

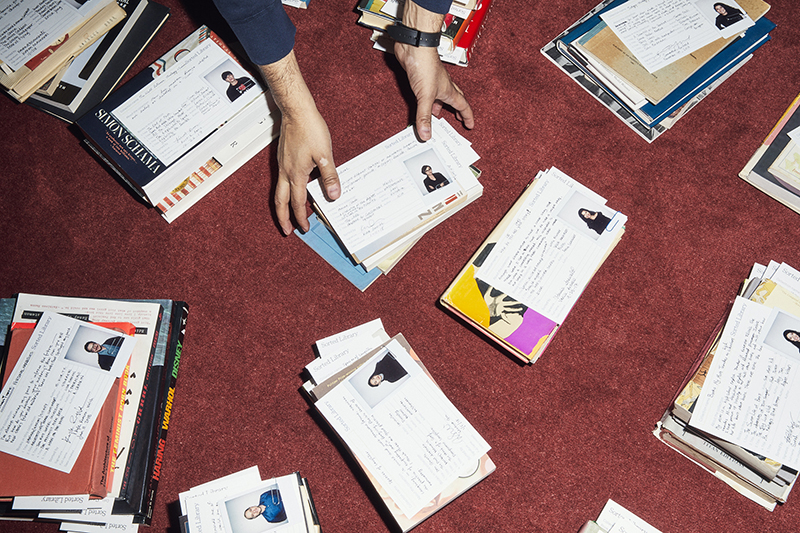

Collections at the Sorted Library. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

Collections at the Sorted Library. Photo by Meredith Jenks.

I spent a few hours at the library one night earlier this year and experienced this feeling for myself. Aujla asked me to make a collection; I had an idea in mind that was thwarted when I couldn’t find my way into it from the books on the shelves. Instead, I grabbed Chekhov’s “Lady with Lapdog and Other Stories.” I remembered reading the title story on a train in Europe after graduating college, a time when I’d felt a vertiginous sense of the possible encumbered by the suspicion that I’d lost my sense of direction. I’d struggled with a similar feeling of rootlessness throughout 2017, after moving back to New York in the wake of multiple major life changes. So, working with the constraints on hand, I attempted a collection about the idea of home, and leaving it.

I included books which addressed that topic quite literally (The Aeneid, the 2005 edition of The Best American Travel Writing, edited by Jamaica Kincaid), and two others (No Country for Old Men, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders) that reflected a less obvious interpretation of it. “This collection explores and integrates journeys away from familiar confines,” I wrote on my catalog card afterward, attempting to explain to myself as much as anyone else why I had chosen the books I had. “Home is a place, a country, an identity, a mode of being, a story you tell yourself. You leave with hope and apprehension, by force or by choice, and you always learn something, even if you never wanted to know it.”

A little maudlin, perhaps, now that I read it back to myself a few months later, though an accurate enough evocation of where my head was at at the time. My collection strikes me now almost like an old diary entry does: the raw rendering of an emotion or thought, distorted by the unreliable lens of the self-regarding self. But anchoring those feelings in the literature at the Sorted Library is a way of elevating them beyond mere solipsism. It establishes the possibility of connection to other library visitors via post hoc discovery. Someone can look through my pile of books at the Sorted Library or scroll through it on Instagram, in the same way I had deciphered some angle on others through their collections. What they’ll find is up to their interpretation.