In January, I got a pre-paid call from John J. Lennon, who was trying to find a home for his newest story, about the difficulty of obtaining books in prison. John doesn’t own a computer or a cell phone, and until last year, he had never used Microsoft Word. So, like a foreign correspondent in the age before the internet, he wanted to dictate his copy to me. My job was to type up the draft and email it to newspaper editors.

Before John decided to become a criminal justice reporter, he lived a life of crime. He now lives and writes one hour north of New York City, in a bare cell in Sing Sing prison. He read me the new story in a soft, staccato voice, making note of every period and comma. “A few years ago, I wrote an op-ed from Attica prison for the New York Times,” he said. “A young man in his senior year of high school wrote to me afterward, and we became pen-pals.” The young man wanted to send him Just Mercy, a book by Bryan Stevenson about racial inequality on death row. But because prisoners can’t receive hardcovers, the student had to photocopy the pages and fold them, five at a time, into envelopes. “I spent the next few days reading Just Mercy, pacing my cell, grinding my teeth, and crying,” John said.

Prison life shapes every story that John reports. He types on a clear-plastic typewriter in a cell with no chair. He conducts many of his interviews in the rec yard, among the joggers and weight-lifters, and he has never been able to Google anything on his own. The prison phone system, accessible for a few hours per day, connects him to just 15 pre-approved contacts. Still, John has become a leading journalist on life inside. His first published story appeared on the website of The Atlantic, and one of his print features will soon appear in Esquire.

In the tenth paragraph of John’s new piece, he read me details that appear in virtually all of his published work. I typed them into the draft. “Sixteen years ago, my drug dealing days came to an end when I shot and killed a man in Brooklyn,” he said. “I tried to get away with it, lost that trial, and wound up with 28 years to life.” Paradoxically, the ugly truth, from a man who once lied under oath, can serve as a kind of invitation—if not to trust John, then at least to keep reading.

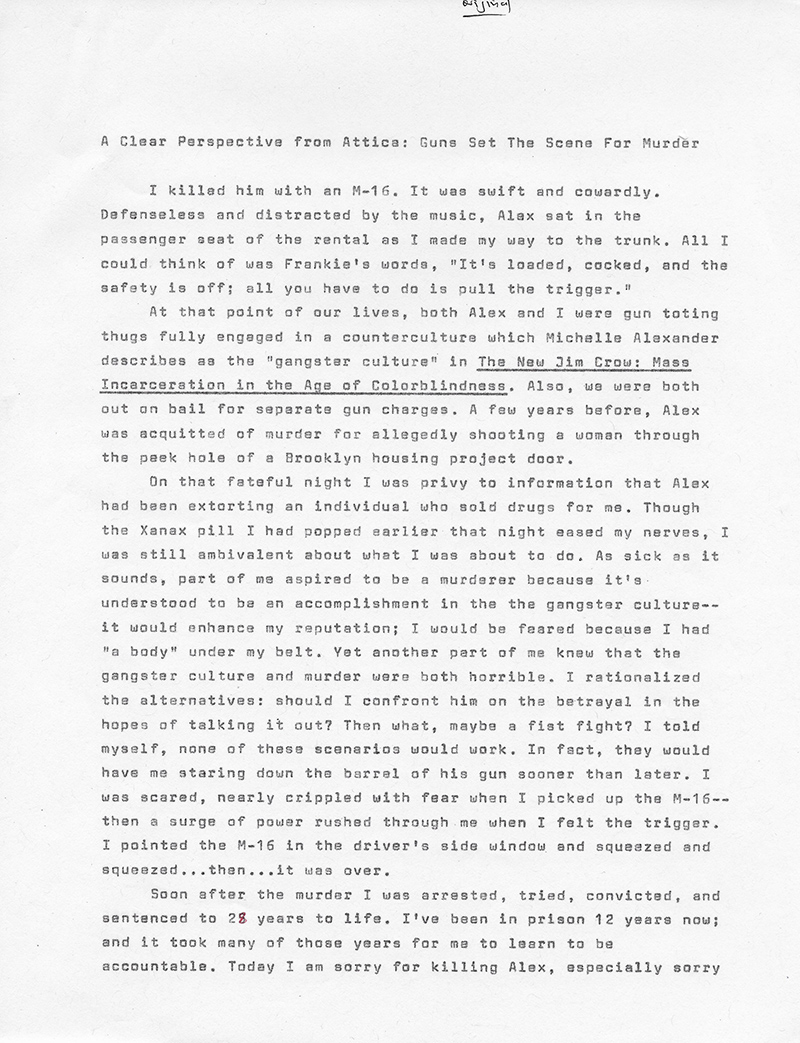

From a draft of John J. Lennon’s article for The Atlantic, “A Convicted Murderer’s Case for Gun Control.”

From a draft of John J. Lennon’s article for The Atlantic, “A Convicted Murderer’s Case for Gun Control.”

John grew up in Sheepshead Bay, on the southern tip of Brooklyn. After his father took his own life, his mother raised him. In fifth grade, John went away to a private boarding school in Garrison, New York, in a converted 19th-century mansion. Old trees towered over the lawn, and classes met in ivy-covered buildings. He never forgot the view of the Hudson River. “It’s the same gorgeous view I look at now,” he told me. At Sing Sing, John can sit on his prison-issue locker, peer through the bars on his window, and see the river. “I often think about that. It’s kind of heartbreaking.”

Boarding school lasted three years, and occasionally John showed promise. In seventh grade, he won a writing contest for a clever bit of historical fiction, told from the perspective of Benedict Arnold’s cane. But that was pretty much the extent of his early writing career. His mother used to remind him, over the prison phone lines: “John, you know you won that award.”

As a teenager, John returned to public school, and he started hanging out with small-time gangsters on the corner. “To a kid that had no father,” John told me, “that was very sexy to me.” Some days, he worked as an usher on Broadway, thanks to a connection of his stepfather, a longshoreman. He’d show up in black-tie attire, only to duck out during break and get stoned. He got to meet Gene Hackman and Richard Dreyfus, but he felt out of place. “You didn’t see them and want to be them. You saw them and wanted to get back to your friends,” he said.

“The ugly truth, from a man who once lied under oath, can serve as a kind of invitation—if not to trust him, then at least to keep reading.”

One summer, he started dating a woman from Bushwick and met a heroin dealer in the neighborhood. “I was so enthralled with that life,” John told me. “I started selling a lot of cocaine, heroin.” He used it, too. He spent a year in jail for a gun charge, but it didn’t change his drug habit. When he got out, he worked his way up the food chain, building a network of sellers in Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan. He made enough money to buy a Jaguar. Some days, he’d go to the movies, bounce from film to film, and daydream about becoming a screenwriter. “In this life—you know, living fast and buying things—I’d always think about writing about it one day,” he said. “I knew I had a story to tell.”

“That life went fast, and ended real fast,” John told me. “I started doing a lot more drugs. A lot of cocaine.” During a few crazed weeks of drug use and dealing, John decided to confront a long-time acquaintance named Alex, whom he suspected of extorting a seller. In a rented SUV, with a witness in the car, he shot Alex with an M-16 assault rifle. “It was a disgusting scene,” John said. “I grew up with him. And you know, I wound up shooting him to death and putting him in the ocean with cinder blocks. In a laundry bag.”

When John speaks of his crime, his voice goes flat. He drains his sentences of energy and emotion, and makes a point of self-effacement. “In that moment, I was still a pretty arrogant, disgusting person,” John told me. He was arrested on separate charges, and during jail time on Riker’s Island, he read about his own crime in the newspaper. “Right away, I was a suspect,” he said. “Alex had washed ashore on a Brooklyn beach.” In a diary from that time, John scribbled occasional observations, rife with misspellings, of addicts and hustlers. But drugs often prevented him from writing, or feeling, anything at all. In other entries, John talked about the lawyer his mother had hired and predicted an acquittal. “I was looking to get away with it,” he told me. He didn’t.

![]()

John keeps his hair neatly trimmed and his broad chin closely shaven. His eyes make him look young, but sometimes he narrows them and looks stern. Sing Sing inmates wear forest-green pants. During my visit, he told me that he started to care about books early in his prison sentence, during a stretch of isolation “in the box” at Upstate Correctional Facility. That was around 2006. At the time, he shared a cell with a guy who’d spent time in college. They talked about their favorite writers. “I was, like, naming John Grisham,” John told me.

The bunk-mate gave him a list of books, which John’s mother bought for him. “She would send anything I ever wanted.” He read Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Johnny’s Got His Gun, by Dalton Trumbo, and he started subscribing to magazines.

Lueggie Dowling, who goes by the nickname Graceful, met John early in his prison sentence, during his own stint in solitary confinement. At first, he considered it a red flag that, in a prison system that’s disproportionately black and Latino, John was white, and well-known among inmates and guards. “I didn’t know who the hell he was. He could have been, like, a school shooter or shit,” Dowling told me, over the phone. But John was in the cell above him, so they started to speak through an air vent. “All we had was that vent,” Dowling said.

John used to talk about writing as a way to make money without selling drugs. “He’s been telling me for the longest time that I should start writing,” Dowling said. The two men became friends, although they rarely saw each other face to face. (They’re now both at Sing Sing.) John later told Dowling, who is serving twenty-five years to life for robbery and second-degree murder, to stop using adjectives and adverbs in order to improve his prose. “He’d say, ‘Get you a New York Times, a New York Magazine, a New Yorker.’”

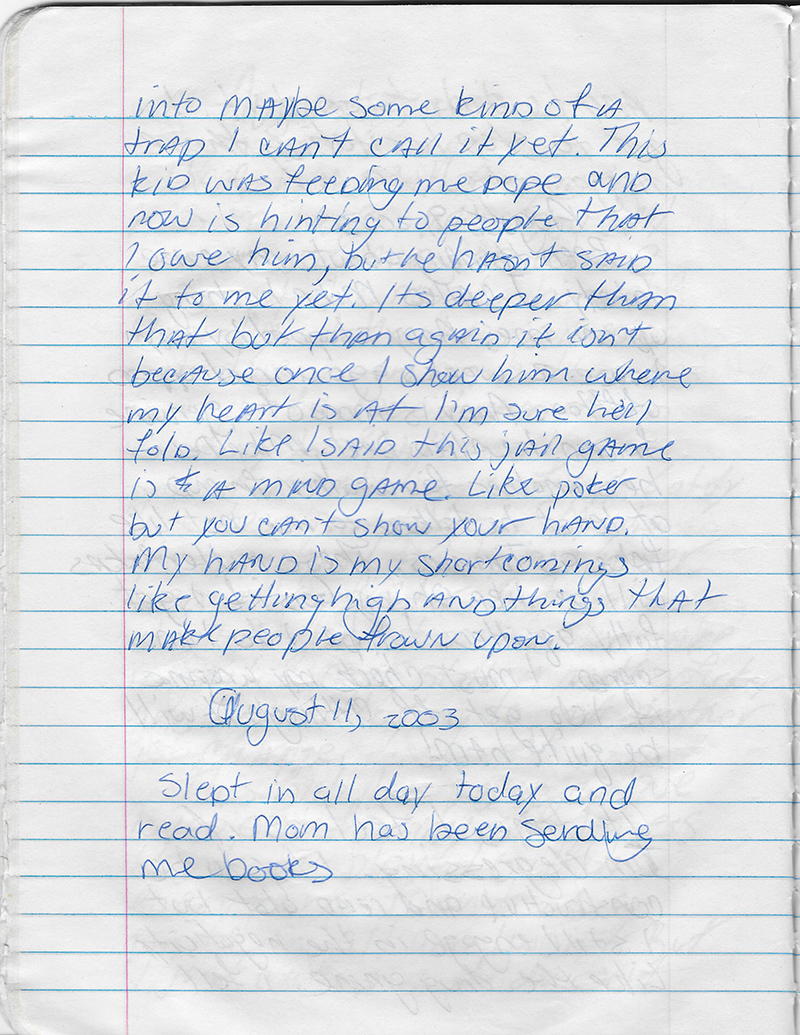

From John J. Lennon’s prison journal.

From John J. Lennon’s prison journal.

John was transferred to Attica prison after he was stabbed with a shank, apparently in retaliation for his crime. It took him months to recover. But he was recommended for a writing program in Attica, and that was where he became a writer: in an overheated brick school building, sitting in heavy desk chairs with a group of fellow inmates. They were all part of the Attica Writers Workshop, run by a Hamilton College professor named Doran Larson. “We’d hang onto his every word,” John said. They read all kinds of nonfiction, often from The Best American Essays, and traded feedback on each other’s writing. “I hear him in my head today,” John said. “With me in particular, he would ding me on my ego.” John’s essays came back with comments like “self-aggrandizing,” or “This is not necessary.”

But ego also gave John a reason to write. He wanted something to feel proud about, and he wanted someone to listen. He used to scold his fellow prisoners for refusing to write about their own crimes, and believed that blunt honesty would earn the reader’s attention, perhaps even their trust. He had been convicted of murder and sentenced to 28 years to life, and he hoped to look that truth in the eye. “At the time, I was serious about my sobriety,” John told me. He attended 12-step meetings and married a woman he met through the mail. “She would always encourage me,” he said. “She was a reader.”

Still, his early breakthroughs led to a breakdown. John started to mail his Attica essays to magazines, and to his amazement, one of them, “A Convicted Murderer’s Case for Gun Control,” was published in 2013 by the website of The Atlantic. That day was a rush of excitement and self-confidence. “It’s like getting high, but better,” John told me. Hungry for more, he kept publishing, which gave him a new swagger. Then, in 2015, he gave in to the temptation to ask a fellow inmate for muscle relaxants, and later Saboxone, a synthetic drug for recovering heroin addicts. Once again, drugs, like writing, offered him a temporary escape. “It took me away.”

![]()

John has been sober for a couple years now. His first published story discussed the violence of his own crime, but these days he writes mostly about the lives of others. After meeting an incarcerated cancer patient named Lenny, in Attica, he wrote a letter to Bill Keller, editor of The Marshall Project and the former executive editor of the New York Times. Keller told me, “The first conversation I had with John was the first conversation I’d had with anybody who was in prison.” He said yes to John’s story. “I still have images of this poor bank robber, making his way through the general population of Attica, carrying a colostomy bag.”

In a series of phone calls, the two men edited the piece, and Keller was struck by how normal it all felt. He was reminded of the years he spent as the foreign editor of the Times, talking with his correspondents on the phone. “It just felt disarmingly familiar,” Keller told me. “I was having the same conversation that I’d had with the Jerusalem bureau chief.” When John needed a statistic or a quote from the outside, Keller and his co-workers would chase one down. “He was one of the first incarcerated people—probably the first—that I actually thought of as a colleague,” Keller told me. “Someone who was in the same line of work that I was in. I had not thought of that.”

His piece for The Marshall Project, where John is now a contributing writer, was one of his first works of reporting and ran under the headline “Dying in Attica.” He described watching Lenny at inmate support groups called Cephas meetings. “As months passed,” John wrote, “Lenny seemed to lose his upbeat swagger.”

He walked the corridors with his head hung, stopped shaving and his scruff grew into a gray beard. He stopped saying hello, stopped sharing in Cephas groups, and seemed to stop hoping. One time while waiting to be called out of the bullpen for a Cephas meeting, other prisoners in the waiting area began to whine about a sewage-like odor that permeated the room. “Ay, yo, who da’ fuck smelling like shit?” one said. Lenny sat shamefaced as other dopey prisoners joined in on the rant and held their shirts over their noses like mean kids on the playground. One prisoner looked at Lenny and said, “Motherfuckas’ need to wash they ass!”

Prison is crude that way. We prisoners just react—to a smell, an observation, a thought—and then blurt out whatever comes to mind. We’re abrasive, socially awkward, devoid of empathy—and we don’t know any better. I only empathize with Lenny because I have Crohn’s disease and, worst case scenario, I may wind up with a colostomy bag or even developing colon cancer myself. So I’d pick his brain about cancer symptoms and pretend to be interested in him, though concerned only about my own ass.

John started to realize that his access gave him an edge on journalists outside the system. “It’s a wide open lane for the prison journalist,” he told me. “There’s plenty of story around me, and within me.” As he wrote in “Dying in Attica,” “I simply see the suffering that most of you don’t.”

Unlike most prisoners, and many freelance writers, John makes a decent living. He isn’t shy about asking his editors for the same rate as writers who aren’t incarcerated. He has a way of convincing even the unlikeliest of people to help him. In 2016, he sent a personal essay called “The Murderer’s Mother” to The Hedgehog Review, a University of Virginia affiliated literary magazine, but his editor, Leann Davis Alspaugh, was repulsed by his crime. “I’m a conservative, straight down the line, and I think that people are responsible for what they do,” she told me. “It’s a very disturbing thing, to find yourself reading deeply into the mind of somebody who has basically gone up to a guy on the street and shot him in the head. And then gone and thrown them in the Hudson.”

Five years ago, Alspaugh told me, she believed that men like John deserved the electric chair. “I never thought I would feel sympathy for someone like that,” she said. But in his story, John wrote sensitively about the pain he had caused his mother, who suffers from Parkinson’s disease. “Mom and I comfort each other from the discomfort of our respective prisons,” he wrote. “She had and still has a bold strength from which I draw my own.”

Alspaugh’s encounter with John challenged her assumptions about prisoners. “I’m tremendously impressed with how resourceful he is,” she told me. She believes the opportunity to write has helped him become a better person. “Maybe it’s part of his rehabilitation.” It has also reminded her of small freedoms that most of us take for granted, like the ability to drive to the store or go out for lunch. After the story came out, John called Alspaugh and asked if she would type up one of his stories, log into a Gmail account under his name, and email it to editors.

“It’s a wide open lane for the prison journalist. There’s plenty of story around me, and within me.”

Aslpaugh now logs into John’s email every few days, on his behalf. He’s a networker. “He knows tons of people that I don’t even know,” Alspaugh said. When I visited him at Sing Sing, he convinced two correctional officers to give us an extra hour together. He suggested that we write a book together. “I think it could be a killer book,” he said, perhaps missing the irony in his choice of words. A couple weeks later, he called and asked me to type up his editorial. At his request, I sent it to an editor at The Guardian, which published it in February.

At times, Alspaugh wonders whether John gained his writing voice, and his hustle, long before he became a writer. “I am very envious of the voice he’s achieved with his work,” she said. His stories are gritty and empathetic; his sentences are short and matter-of-fact, even when they discuss drug dealing and murder.

Lately, though, John has explored subjects that once made him uncomfortable, like mental illness and the experiences of gay inmates. “That’s when I know it’s a good story, when it pushes me out of the comfort zone,” John told me. “I have to feel something in the story, when I’m writing.”

Not all prisoners respect his status as a reporter. But at times, his dual identity helps him cross the racial and political fault lines of prison life. Inmates in the rec yard watch him while he conducts interviews. “You’ve got to kind of wonder what the crowd is thinking,” John said. “A lot of the guys respect him, so they’re willing to give him a bit of time,” said Dowling, the fellow prisoner. “I think he sees that there’s an ability to perceive the things around him, capture it on paper, and make sure that everyone who’s not in this situation knows about it.”

In 2003, before John called himself a writer, before he was convicted of murder, he scribbled in the green composition book that he used as a diary. One entry, written in the cursive script he once practiced in boarding school, is neater than any of the others. “I say I’ll write a book one day,” John wrote.

I kind of want to see the outcome of me, see if I win at trial. I kind of want a happy ending. Everybody loves happy endings. My happy ending of course would be getting out of this system and taking some writing classes.

Maybe there are no happy endings in a story like John’s. He won’t be eligible for parole until 2029. But he got those writing classes, and he calls me every week, to talk about his book.