Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2022

196 Books We're Looking Forward to This Year

And just like that . . . 2021 is over. Like any year, it had its share of disappointments, triumphs, and scandals. There were some good books published and some good literary adaptations to watch. There were great book covers, great book reviews, and even (if we do say so ourselves) a few great pieces published in this very space.

But now it’s 2022, and it’s time to dream it all up again. If there’s anything we’ve learned in the last two years, it’s that nothing is certain—but we can be fairly sure that we’ll get to read a bunch of good books in the new year (though publication dates are even softer than usual these days, so be warned that all of the below is subject to change). Here are the ones we’re most looking forward to—so far.

JANUARY

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers

Simon & Schuster, January 4

At the beginning of this novel, set in a near-future Philadelphia, a mother has a very bad day. She leaves her young daughter alone for two hours, and is reported, observed, and finally sent away to the titular school, a sort of rehab where she and other “bad” mothers must endure what amounts to psychological torture in the name of “training.” This is a chilling dystopian novel about what we expect from mothers (complete self-abnegation) and fathers (something less than that), and the horrifying possibilities of the surveillance state—all of it made all the scarier by its essential plausibility. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Jean Chen Ho, Fiona and Jane

Viking, January 4

Jean Chen Ho’s debut collection follows two young Taiwanese American women, Fiona Lin and Jane Shen, best friends since elementary school. They see each other through firsts, through early fumbling years and questionable LA bars. From alternating perspectives, we watch as they grow up and away from one another. Fiona moves to New York to help a sick friend, while Jane stays in California and grieves the death of her father. Still, despite the years and the distance, there are some friendships you keep coming back to. There are a lot of metaphors out there to describe the ebb and flow of far-flung friendships like this, but perhaps the most apt is that of a planet orbiting around a star. (Don’t we all have relationships that make us feel like a secondary character at times?) Fiona and Jane so precisely captures a lot that’s left unsaid in strong female friendships: small resentments that build over time, even outright betrayal. It’s a three-dimensional portrayal of their bond—the good and the bad. There is love here, and refreshing honesty, too. If you are lucky, you have had a friend like this in your life, a friend who you might want to share this book with. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Xochitl Gonzalez, Olga Dies Dreaming

Flatiron, January 4

Olga is a wedding planner for Manhattan’s power brokers; her brother Pedro is a popular congressman representing their gentrifying Latinx Brooklyn neighborhood. They’re publicly successful—until their mother, who abandoned them, returns to their lives. Says Rumaan Alam about Gonzalez’s debut, “The extraordinary accomplishment of Olga Dies Dreaming is in how a familiar-enough tale—a woman seeking love, happiness, and fulfillment in the big city—slowly reveals itself to be something else altogether.” –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

Leonard Mlodinow, Emotional: How Feelings Shape Our Thinking

Pantheon, January 11

An eye-opening investigation into the two sides of the brain (emotional and rational), and how to value and balance both, Emotional explores what happens when we ignore (and accept) our feelings, and positions itself as a guide for how to listen to our bodies and minds in a way that will create the equilibrium we crave. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Kathryn Schulz, Lost & Found

Random House, January 11

I’m probably not the only one who first encountered Kathryn Schultz’s work through her Pulitzer Prize–winning New Yorker piece “The Really Big One,” about the earthquake that’s predicted to someday destroy the Pacific Northwest. (If you want to feel Truly Aged, that ran in 2015.) I can’t help but feel that Schultz’s memoir is an extension of that project. Lost & Found intertwines the death of Schultz’s father with the love story of her marriage, exploring the inseparability of grief and joy and “how private happiness can coexist with global catastrophe.” As we enter Pandemic Year Three, this feels like one to read. –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Lewis R. Gordon, Fear of Black Consciousness

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, January 11

Professor Lewis R. Gordon, the Philosophy Department Head at the University of Connecticut, offers an expansive nonfiction work that critically examines the historical roots of “racialized Blackness” and how this school of thought is shaped by the institution of whiteness. Gordon includes personal experiences, striking a fine balance between the searing imprint of memory and the accumulation of learned knowledge. Gordon points out how anti-Blackness is not only a global commodity but a weaponized form of oppression that even members of the Black community can perpetuate through colorism. His take on the Marvel blockbuster Black Panther raises questions about the world’s view of Africa and the legacy of colonial violence. This book is certainly not a light, breezy read, but Gordon’s surprising observations crack open the mind to connect various creative disciplines. –Vanessa Willoughby, Associate Editor

Hanya Yanagihara, To Paradise

Doubleday, January 11

Is it possible for another book to be as completely devastating as A Little Life? Probably not, but Yanagihara’s new novel is another big, bold story of many lives and many loves that promises to be just as engaging (and, let’s be honest, it’ll probably destroy all of us too). Three strands—an alternate 1893 America, 1993 AIDS-devastated Manhattan, and a totalitarian future ridden by plagues—converge in New York in a story of illness, loss, family, and love. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Jami Attenberg, I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home

Ecco, January 11

I was so excited when I heard whisperings that novelist Jami Attenberg was coming out with a memoir in 2022, and that was before I learned she’s writing about some of my favorite topics to spend time with: art and class, friendship and singlehood, and carving out a life that Just Fits. Liz Moore called it “one of the most artistically invigorating books” she’s read in years, which feels like a perfect read for January, no? –ES

Hannah Lillith Assadi, The Stars Are Not Yet Bells

Riverhead, January 11

National Book Foundation 5 Under 25 honoree Hannah Lillith Assadi’s wonderful first novel, Sonora, was one of the most beautifully wrought debuts of recent years, so I’m tremendously excited to read her sophomore effort. In The Stars Are Not Yet Bells, an elderly woman with Alzheimer’s casts her failing mind back to 1941, when she and her new husband left New York City for a remote island off the coast of Georgia in a doomed quest to find the mysterious blue jewels that were said to lie at the bottom of the ocean. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor in Chief

Antoine Wilson, Mouth to Mouth

Avid Reader Press, January 11

When an unnamed narrator runs into a former (half-remembered) college classmate in an airport, the man recounts the story of resuscitating a drowning stranger on a beach, and subsequently becoming obsessed with the life of the man, a renowned art dealer who does not initially reciprocate his savior’s curiosity. The New York Times called it “an enthralling literary puzzle,” which, coupled with the Highsmith echoes, is more than enough to pique my interest. –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Carl Bernstein, Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom

Henry Holt, January 11

Carl Bernstein, of All the President’s Men fame, delivers a memoir of a life spent in some of the most fast-paced newsrooms in the country. As early as 16, Bernstein realized that he didn’t care about high school—he cared about news. He began his career as a copyboy at the Washington Star, was a reporter by 19, then moved on to greater heights. By the time he made it to the Washington Post, he had never gone to college, but had received years of hands-on education in investigative journalism. –JH

Gwen E. Kirby, Shit Cassandra Saw: Stories

Penguin Books, January 11

You had me at “Margaret Atwood meets Buffy,” but also at the title story, “Shit Cassandra Saw That She Didn’t Tell the Trojans Because at that Point Fuck Them Anyway.” If the rest of this debut collection has the same kind of irreverent energy and self-assured risk-taking, I predict great things. –ET

Claire Messud, A Dream Life

Tablo Tales, January 15

The novels of Claire Messud contain sharp edges in just the right places, and glint with an insight that both cuts and beguiles. A Dream Life is the compact, densely packed story of a family dislocated from New York to Sydney, Australia in the 1970s, and the small dramas that ensue. Messud always seems to have perfect command over the characters she creates (and the life that accrues around them), letting them falter through regret and self-deception without punishing them too severely because, after all, like us, they’re all too human. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Sara Freeman, Tides

Grove, January 16

Grief is a shapeshifting beast; it takes root in everyone differently. For Mara, it manifests as a desire to run away. After an unspeakable earth-shattering loss, she leaves her family and winds up in a vacation town by the sea with next to nothing. In glinting, spare prose, we can see the outlines of her new life: By day, she searches for food. By night, she drowns out the world by swimming further into the dark. But you can’t block out reality forever. It finds a way of seeping in. In a material sense, the money finally runs out, and she’s forced to find work at a local wine shop. In an emotional sense, she has to face what she’s fled from if she is ever going to pursue an honest relationship with the shop owner. It’s a beautiful portrait of a woman unmoored—and the connections that bring her back. –KY

Sequoia Nagamatsu, How High We Go in the Dark

William Morrow, January 18

This impressive, far-reaching debut begins in 2030, as an archaeologist arrives in the melting Arctic Circle, where he finds no trace of his lost daughter, but does find the discovery that entranced her: the remains of an ancient child whose body, it turns out, holds an equally ancient virus. So yes, this is a plague novel, a pandemic novel, one that both honors individual tragedy and asks us to widen our perspective—to look to the future, to the stars. The chapters, which feel like linked short stories, jump decades and centuries, imagining the long-term effects of the Arctic Virus on the world and even the galaxy, without losing touch with the smaller stories of the humans who must contend with it. –ET

Zora Neale Hurston, You Don’t Know Us Negroes

Amistad, January 18

The rediscovery of any piece of writing by Zora Neale Hurston is a cause for celebration, so this 460-page bumper collection of pieces feels almost like an embarrassment of riches. Spanning more than 35 years, You Don’t Know Us Negroes is the first comprehensive collection of essays, criticism, and articles by the legendary Harlem Renaissance author, covering topics like the birth of the Montgomery bus boycott, the integration of schools, the desegregation of the military, and the trial of Ruby McCollum. This fiery chronicle of Black life in America through the eyes of one of the greatest literary figures of the 20th century is not to be missed. –DS

Bernardine Evaristo, Manifesto: On Never Giving Up

Grove, January 18

Bernardine Evaristo made history in 2019 when she became the first Black woman and first Black British person ever to win the Booker prize. That landmark victory brought with it a legion of new fans, all of whom will surely be eager to read her highly anticipated nonfiction debut. Manifesto is a hybrid work—part memoir, part advice manual for struggling creatives—which charts Evaristo’s remarkable life and rebellious career from her early years as one of eight children in a mixed-race family, to her setting up of Britain’s first Black women’s theatre company, to her steadfast determination to write the books that were missing from Britain’s bookshelves. An illuminating and inspirational window into the life of a brilliant artist, determined to make her mark. –DS

Brian Cox, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat

Grand Central, January 18

If Brian Cox’s lifetime of legendary performances doesn’t convince you to read his memoir, how about the fact that he apparently pulls no punches when it comes to his fellow fame-os, from Johnny Depp (“so overblown, so overrated”) to Quentin Tarantino (“I find his work meretricious”). I’ve been saying it for years: more salty celebrity memoirs! –JG

Charles J. Shields, Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind A Raisin in the Sun

Henry Holt and Co., January 18

This thoroughly researched biography focuses on the personal life and literary legacy of Lorraine Hansberry. Readers learn about Hansberry’s family background and how her upbringing shaped her politics. Shields doesn’t present a romanticized version of Hansberry’s journey to artistic visionary—the playwright’s flaws and insecurities are shared alongside her strengths. Shields also devotes considerable attention to the literary influences that inspired Hansberry, which included James Baldwin, Sean O’Casey, and Simone de Beauvoir. Hansberry’s romantic relationships with women aren’t treated as a character deficit or fleeting fancy but an undeniable component of her evolution as an actualized person and a creative. Overall, Shields’s portrait of the playwright, who died too soon at the age of 34 from pancreatic cancer, is a rich ode to a trailblazer who refused to conform to society’s expectations of Blackness, queer identity, and the role of a Black author. –VW

Andrew Lipstein, Last Resort

FSG, January 18

Here’s some literary catnip for you: 27-year-old Caleb, casting about for some purpose in life, has a semi-random encounter with a college acquaintance who tells him a great story—which Caleb then uses as the backbone for a novel. Unfortunately for Caleb, said acquaintance works in publishing, which means he’s caught, so to speak, while the book is still on submission, which results in a welcome and twisted deviation from the usual plagiarism plot. But the question remains: whose novel is it? And what does each of them—the one who lived it, the one who wrote it—deserve? Soon Caleb finds himself in a slow-motion literary-world car crash, but it’s so horribly delicious that the reader (especially the reader who is also a writer) won’t even dream of looking away. –ET

Bill Hayes, Sweat: A History of Exercise

Bloomsbury, January 18

Part history, part travelogue, part memoir, Sweat tackles the rich topic of exercise (distinct from sports), from Hippocrates to Jane Fonda. I’m fascinated by the evolution of exercise culture, and I look forward to learning about how we got from those vibrating belts to HIIT (and maybe whether we can expect a return to the vibrating belts anytime soon, because they seem a lot more fun). –JG

Kendra James, Admissions

Grand Central Publishing, January 18

I went to public school, but for some reason, I’m fascinated by the narrative possibilities that can happen with private education. Kendra James, a founding editor of Shondaland.com, offers a memoir about her time at The Taft School, a coeducational, private school in Connecticut. James was the first Black legacy student and a few years later, became an admissions officer who focused on diversity recruitment for independent prep schools. This role eventually caused James to reflect on her past and the inequities of the American education system. There is plenty of fiction and nonfiction works about private schools, but James’s perspective as a young Black woman navigating the hierarchies of this world is not as common. –VW

Weike Wang, Joan is Okay

Random House, January 18

I’ve been waiting for the next novel from Weike Wang since her excellent 2017 novel Chemistry, which managed to be a campus novel, a work novel, a love story, and an examination of modern consciousness all at the same time. Joan is Okay lifts us from the PhD world into the world of a busy NYC ICU, which only makes sense, but Wang’s underlying concerns of identity, family, and culture seem to be well intact here. Can’t wait to read more from her. –ET

Carl Erik Fisher, The Urge: Our History of Addiction

Penguin Press, January 25

In his nonfiction debut, physician and bioethicist Carl Erik Fisher charts the history of addiction treatments through medicine, science, literature, religion, public policy, and his own alcoholism and recovery. Through a blend of memoir and research, Fisher’s created a call to reconsider how we discuss, treat, and politicize addiction. –WC

Isabel Allende, Violeta

Ballantine, January 25

The internationally acclaimed Isabel Allende’s latest book—following novels including The House of the Spirits, Of Love and Shadows, Eva Luna, Paula, and In the Midst of Winter—comes in the form of a letter from protagonist Violeta Del Valle, who, at 100, has lived through many of the major events of modern history. Allende is an extraordinary storyteller, and I’m excited to see where she takes this character. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

John Darnielle, Devil House

MCD, January 25

The man behind The Mountain Goats is a rising star in the literary fiction world, and with very good reason. Darnielle’s marvelously unsettling Wolf in White Van (about a reclusive and severely disfigured video game designer) and Universal Harvester (about a 90s Iowa video store clerk who discovers that someone has been modifying the VHS tapes…) were both critically acclaimed and nominated for major awards. His new novel, the deliciously titled Devil House, is the story of a once-successful true-crime writer who moves into a California house where a pair of murders took place during the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s. Expect the unheimlich. –DS

Morgan Thomas, Manywhere

MCD, January 25

So far, I’ve only read one of the stories from Thomas’ debut collection, but it was more than enough to move this one to the top of my list. Louie, the narrator of “Bump” is a trans woman who longs for a child so much that when a coworker asks if she is, Louie can’t deny it. Instead, she buys several prosthetic bumps on the internet and keeps up the illusion. The story is compelling and humane and lovely, and I can’t wait to read the whole collection, which Kirkus calls “a visionary and keenly observed debut.” –JG

Gish Jen, Thank You, Mr. Nixon

Knopf, January 25

Gish Jen’s The Resisters was one of my favorite reads of 2021, so you better believe I’ll be snapping up her collection. Thank You, Mr. Nixon captures the 50 years since Nixon’s historic trip to China, probing US-China relations through the journeys of her characters. –ES

Eileen Pollack, Maybe It’s Me: On Being the Wrong Kind Of Woman

Delphinium, January 25

Too smart, too independent, too insubordinate: Eileen Pollack found herself, growing up in the 1960s, not the right kind of girl. This humorous collection of essays charts a life lived in defiance of society’s rules for women, from anecdotes about childhood to the trials of online dating in your sixties in New York City. –CS

Renée Branum, Defenestrate

Bloomsbury, January 25

Branum’s dazzling debut novel combines a contemporary story of familial alienation and grief, the history of a family curse that entails untimely death via splat, and meditations on falling (prat, à la Buster Keaton; in love; from an airplane, becoming legend). Told in a series of vignettes, Defenestrate feels less fragmentary than tightly woven, and with every sentence shimmering. At points I had the sense of visiting a tiny and lovingly curated archive. The novel is lyrical and lovely and slyly funny, yet deceptively propulsive. One to stay up all night reading and immediately begin again. –JG

Mesha Maren, Perpetual West

Algonquin, January 25

In Maren’s follow up to her excellent, claustrophobic Sugar Run, a young couple moves from Virginia to El Paso, where they begin to unravel: Alex lured across the border to Mexico by lucha libre and love; Elana losing touch with the things that once tethered her to herself. The publisher’s description promises missionaries, wrestling matches, a cartel compound, and an investigation of “the false divide between high and low culture,” which all sounds pretty good to me. –ET

Imani Perry, South to America

Ecco, January 25

Imani Perry blends reportage, memoir, and travelogue in this introspective, probing study of the American South. Perry unpacks the stereotypical markers associated with the South, showing how the South holds the key to understanding the evolution of our nation. A guiding theme of the book shows how environment can shape people—physically, mentally, and emotionally. In the introduction, Perry writes, “Its [the South’s] legacy of racism then is… bloodier than most. But other regions are also bloody in deed. Discrimination is everywhere, but collectively the country has leeched off the racialized exploitation of the South while also denying it.” Perry’s seamlessly crafted work is a tour-de-force reckoning. –VW

FEBRUARY

Julia May Jonas, Vladimir

Avid Reader Press, February 1

Oh snap. This debut novel is compulsively readable, deliciously wicked, and extremely fun—not least because it contains all of my favorite things: obsession, sex, academics, literary ambition (thwarted and non), a sharp-edged narrative voice that you can’t quite pin down (morally, anyway). It also contains something that I didn’t expect, though should have, considering the premise—a professor becomes infatuated with a new hire while her husband faces a termination hearing for sleeping with his students: a clear-eyed and judicious examination of the current social climate at universities. –ET

Carl Phillips, Then the War: and Selected Poems, 2007-2020

FSG, February 1

With the incomparably gorgeous, deftly poetic sentences that make up his work, Carl Phillips has been exploring intimacy, sexuality, and interiority for more than a decade. Then the War promises to be a treasure, including new poems as well as a selection of past work, the prose memoir “Among the Trees,” and the chapbook Star Map with Action Figures. –CS

Olga Ravn, tr. Martin Aitken, The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century

New Directions, February 1

A spaceship, a workplace, a faded memory of Earth. Ravn’s sci-fi novel, made up of a series of witness statements, follows the Six-Thousand Ship and its human and not-quite-but-almost-human crew members. When objects from the planet New Discovery end up on the ship, the crew members develop a strange attachment to them, yearning for warmth and affection, the things and moments from Earth. Picking at the seams of productivity, Ravn’s novel ultimately illuminates the kinds of longings that sit at the center of human beings, and the complicated state of being human. –Snigdha Koirala, Editorial Fellow

Kim Fu, Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century

Tin House, February 1

I love reading the descriptions of short story collections—they’re little treasure chests of weirdness. This one sold me on descriptions such as “a runaway bride encounters a sea monster” and “an insomniac is seduced by the Sandman.” I never knew I wanted to read a Sandman seduction story, but reader, I do. –ES

Lan Samantha Chang, The Family Chao

W.W. Norton, February 1

Chang’s latest novel—her first in a dozen years—is a reimagining of The Brothers Karamazov set in a family-owned Americanized Chinese restaurant in small-town Wisconsin. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called the novel “timely, trenchant, and thoroughly entertaining.” I can’t wait to devour it. –JG

Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Jennifer Croft, The Books of Jacob

Riverhead, February 1

Nobel Prize winner Tokarczuk’s massive (seriously massive, at 995 pages) historical novel follows the rise and fall of a mysterious messianic religious leader in eighteenth century Europe. Jacob Frank traverses empires with his disciples – born Jewish, he converts to Islam, then Catholicism, is labeled both a heretic and a Messiah. The book was an instant best-seller and won Poland’s most prestigious literary prize, so despite the impressive bulk, this is at the top of my TBR list. –EF

Toni Morrison, Recitatif: A Story

Knopf, February 1

First published in 1983 in Confirmation: An Anthology of African American Women, edited by Amiri Baraka and his wife Amina Baraka, Recitatif is the only short story written by the powerhouse novelist. The title is a reference to the French form of “recitative,” a musical styling that is often used in operas. The story centers on childhood friends Twyla and Roberta, who drift apart as they grow older. The former confidantes find that although they now believe in conflicting ideologies, there is still an indescribable bond between them. Morrison purposely doesn’t identify which woman is Black and which is white and described the story as “an experiment in the removal of all racial codes from a narrative about two characters of different races for whom racial identity is crucial.” Morrison’s sharp-eyed treatment of race, racism, and racial hierarchies remains relevant, digging deep into the marrow of society’s maladies. –VW

Heather O’Neill, When We Lost Our Heads

Riverhead Books, February 1

Heather O’Neill’s historical fiction novel combines two of my favorite topics: destructive female friendships and high society snobs behaving badly. Set in 19th-century Montreal, the narrative centers on Marie Antoine, the daughter of the richest man in the city, and Sadie Arnett, a scheming newcomer who seems to be cut from the cloth of Becky Sharp. The two frenemies lose touch and then later reconnect. Sex, lies, drama, deception, and glamour—sign me up! –VW

Rebecca Mead, Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return

Knopf, February 8

Rebecca Mead, a New Yorker staff writer, brings us the story of resettling in one’s own homeland and reckoning with its changes over time. Mead moved back to London in 2018 after living in New York City for three decades, and this book, a reported memoir, portrays the evolution of her relationship with the city and her examination of what it has become. –CS

Sarah Manguso, Very Cold People

Hogarth, February 8

Sarah Manguso’s debut novel—need I say more? I mean, I will for posterity. Very Cold People (a title after my own heart) is about a girl named Ruthie reckoning with the sins and constraints of her small Massachusetts hometown. Manguso’s made a name for herself in nonfiction with her slim-yet-weighty lyrical books including The Guardians and 300 Arguments, and I can’t wait to see how her style translates to fiction. –ES

Kiare Ladner, Nightshift

Custom House, February 8

This exciting debut by Kiare Ladner revolves around the friendship between Meggie and Sabine—but possibly “friendship” is too strong a word. It’s more like a fixation, a decision on Meggie’s part to emulate and follow Sabine to the ends of the earth. Meggie meets Sabine at work, and even though Meggie seems to have all the facets of a good life (stable job, boyfriend, education), when she meets Sabine, she would, and does, throw it all away just for the chance to live alongside her. When Sabine trades her hours for the nightshift, so too does Meggie, and they begin living their nocturnal life together, exchanging the plain ease of daytime and boyfriends and normalcy, for the mystery and liminality of the night, and all it shrouds and reveals. –JH

Chuck Klosterman, The Nineties

Penguin Press, February 8

I’ve loved Chuck Klosterman’s incisive cultural criticism ever since reading the absurdly fun Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture Manifesto. Now, The Nineties promises a deep dive into the decade of grunge and the last one before the internet infiltrated every single part of how humans relate to one another. It’s an era that happened so recently that we still don’t understand it—and, in Kloserman’s view, this is the perfect time to try to make sense of it all. –CS

Coco Mellors, Cleopatra and Frankenstein

Bloomsbury, February 8

Cleo is a 24-year-old painter with an expiring student visa; Frank is 20 years older and financially stable (and then some). Their “impulsive marriage” sets off all sorts of reactions in their circle of friends and family—not to mention their individual reactions as they settle in as husband and wife. It’s giving me early-season Girls vibes, which I’m very much here for. –ES

Sasha Fletcher, Be Here to Love Me at the End of the World

Melville House, February 8

Poet Sasha Fletcher’s debut novel is a love story (good) about a freelancer (relatable) in Brooklyn (yes) in winter (nice) with a strange President (classic). Says Alexandra Kleeman, “This book roils with beauty, with enthusiasm, with love for both the minuscule and oversized wonders of the world.” I believe her. –WC

Heather Havrilesky, Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage

Ecco, February 8

I’m a longtime fan of Heather Havrilesky’s “Ask Polly” columns (once at New York Magazine and now on her Substack); even when they’re about something specific and bonkers—like the person whose in-laws were trying to poison her with mushrooms—Havrilesky always manages to make them accessible, familiar, hilarious, and life-affirming. I expect nothing less from her new book, Foreverland, though it’s not a book of advice, per se. This time Havrilesky is turning towards herself—and her marriage and family—and revealing it to the world. She has woven these ideas in to her advice columns in the past, but never have we been treated to such a broad examination of modern marriage, with her own experiences at the core. Both married and unmarried audiences will find something to cherish in this book on what it means to have a good marriage, what a marriage is at all, and how to retain one’s identity, as well as desires, in the face of binding yourself to another. –JH

Ella Baxter, New Animal

Two Dollar Radio, February 15

In this raw, arresting novel, Amelia Aurelia—a cosmetic mortician—goes into a tailspin after the death of her mother. Included in the tailspin are: a trip to Tasmania, an uncertain communion with her birth father, dating apps, a BDSM club, kink-related paperwork, a horse head, painting a man’s face with menstrual blood, mean texts. Ultimately, is a book about something that seems obvious, but so often isn’t: the inextricability of mind and body, and the importance of our connections with other people. –ET

Marlon James, Moon Witch, Spider King

Riverhead, February 15

The second novel in Booker Prize-winner Marlon James’ Dark Star trilogy (aka his “African Game of Thrones”), Moon Witch, Spider King shifts its focus to Sogolon the Moon Witch (who, as you may recall, clashed with Tracker in the latter’s search for a disappeared boy in Black Leopard, Red Wolf). In this installment, Sogolon gives her own account of what happened to the boy, and of the century-long feud she had with the powerful and sinister Aesi, chancellor to the king. Told with James’ inimitable linguistic verve, this promises to be another riotous, ultraviolent, dazzlingly inventive epic in an already-groundbreaking saga. –DS

Danielle J. Lindemann, True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 15

Like many people, when I need to detach my brain, I indulge in the absurdity of reality TV. I’m not a Real Housewives person, but I do dip into Bravo’s other offerings like Below Deck and Summer House. And as someone who is a self-identified pop culture nerd, I do think that our reactions and interpretations of reality TV can reflect our culture. Danielle J. Lindemann’s book seems like a sharp sociological analysis of how race, gender, and class intersect within the genre. –VW

Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell, Chilean Poet

Viking, February 15

Who doesn’t love a novel about poets? Poets are like regular people but with extra feelings; this is why they make incredible fictional subjects for love stories and tragedies and capers and mysteries and… all of the above? So I can’t wait to get my hands on Zambra’s latest, which advertises its subject matter in the title, and follows a young poet in Santiago, Chile as he navigates life among his two families, the chosen (poets!) and the actual (also poets). –JD

Dennis Duncan, Index, A History of the: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age

W.W. Norton, February 15

Nowadays, we take the search function for granted; but it was a long road to get here. Dennis Duncan’s full-length nonfiction debut catalogues the life of the index, the humble but mighty index, from thirteenth-century European monasteries to present-day Silicon Valley. As the ways we read expand and morph—into ebooks, Substacks, Patreons, NFTs—it’s worth taking a look back at the history of how we’ve organized what we know. It’s the age of information, but it always has been. –WC

James Curtis, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life

Knopf, February 15

It always seems that multiple books about an icon emerge at the same moment: and it is now filmmaker and actor Buster Keaton’s time to shine. Curtis’s offering is a definitive biography that delves into the mystery behind the man who made America laugh in the early years of film. Curtis, the author of biographies of stars like Spencer Tracy and W.C. Fields, now turns his gaze on Keaton, telling stories of his early vaudeville years with his family, contract disputes, his struggle with drinking, and problematic ex-lovers. –JH

Tanaïs, In Sensorium: Notes for My People

Mariner Books, February 22

The power of scent, specifically its ability to preserve memories, cannot be overstated. I love my little collection of perfumes and get the same amount of delight and satisfaction out of the “low-end” celebrity perfumes (Princess of Pop Britney Spears really does have some nice, inexpensive perfumes!) as I do the opulent designer offerings (I’m coming for you, Tom Ford’s Black Orchid!). Using their personal experiences and identity as an American Bangladeshi Muslim as a narrative framework, Tanaïs examines the role of fragrance in South Asian history. Tanaïs is also an independent perfumer and beauty designer, so I’m interested in seeing how they blend their industry knowledge with the vulnerability of memoir. –VW

Quan Barry, When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East

Pantheon, February 22

This novel couldn’t be any more different from Quan Barry’s deliciously irreverent 2020 novel We Ride Upon Sticks—except that it is similarly excellent, and similarly immersive, a full-throated plunge into a very specific, fascinating world. When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East is technically about twin brothers—one of whom is a monk, the other a former monk—on a quest to find the reincarnation of a famous lama in Mongolia, but it is really much more about Buddhism, love, and the metaphysics of being. –ET

Jane Pek, The Verifiers

Vintage, February 22

I first became familiar with Jane Pek after reading her short story “Portrait of Two Young Ladies in White and Green Robes (Unidentified Artist, circa Sixteenth Century)” in Conjunctions. I was so taken in by her descriptive language and lush, immersive imagery. The story’s narrator is unabashedly vulnerable, her confessions loaded with the heaviness of regret. Pek’s debut novel is a contemporary mystery and centers on amateur sleuth Claudia Lin, who defies her parents’ traditional gender roles and gets a job at a dating detective agency. When a client disappears, Claudia finds herself entangled in a web of deceit. Pek has already proven that she’s adept at crafting the rich inner world of her characters, so I’m looking forward to her take on genre fiction. –VW

Julie Otsuka, The Swimmers

Knopf, February 22

I remember the exact moment I read the opening pages of The Buddha in the Attic. I was in the Union Square Barnes and Noble and I opened a book on the new releases table. I had finished my first year of an MFA and was pretty sure I knew what writers were allowed to do. I ended up reading half that novel, standing at that same table, a story written in first person plural about Japanese picture brides immigrating to America in the early 1900s. It was beautiful and perfect, and now we get The Swimmers. Otsuka’s new novel is about a group of (rather obsessed) recreation swimmers and what happens when a crack appears at the bottom of their pool. Alice, one of the swimmers who is cast out into non-pool life, must then grapple with haunting memories of her childhood and the Japanese American internment camp as well as the reappearance of her estranged daughter. Otsuka is a beautiful writer and The Swimmers promises to be brilliant. –EF

Sarah Weinman, Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free

Ecco, February 22

In 1957, a teenage girl named Victoria Zielinski was murdered by a man named Edgar Smith. For the duration of the 60s, while in prison for the crime, Smith wrote numerous pleas for the overturning of the conviction, including to William F. Buckley Jr. In 1971, Edgar Smith was released, in large part thanks to Buckley, who led a campaign on his behalf, being apparently unable to believe that someone who held him (and his conservative beliefs) in such high regard could be a murderer. In 1976, Smith attempted murder again, and was finally shut away for life. Sarah Weinman does an impeccable job with this wild story of murder, celebrity, politics, and the American ability to put unsavory characters on a pedestal. –JH

MARCH

Sarah Krasnostein, The Believer: Encounters with the Beginning, the End, and our Place in the Middle

Tin House, March 1

A fascinating portrait of the human condition, Sarah Krasnostein’s latest explores a range of belief systems through six profiles—of a death doula, a geologist, a ghost-hunting neurobiologist, ufologists, a woman accused of murder, and Mennonite families living in New York. A great read for our “deeply fractured times,” as they say. –ES

Margaret Atwood, Burning Questions

Doubleday, March 1

What I would give to live inside the mind that brought us The Handmaid’s Tale! Burning Questions offers us a generous, enjoyable glimpse. It takes a special kind of writer to bring such a wide variety of topics under one roof. Here we have: the power of storytelling across cultures, Trump, the pandemic, the climate crisis, zombies—yes, zombies. Many of these topics may be timely, but I’m sure there is sage wisdom in here for the ages. All hail Margaret Atwood! –KY

Missouri Williams, The Doloriad

MCD x FSG Originals, March 1

This book sounds extremely up my alley: lyrical, visceral, depraved, demented, a post-apocalyptic Greek tragedy (read: an incestuous family whose Matriarch dreams of singlehandedly rebooting humanity) run through with VHS tapes and madness. Plus, Mary South compared it to Geek Love! I am sold. –ET

Pankaj Mishra, Run and Hide

FSG, March 1

Pankaj Mishra is an exceedingly elegant systems thinker; his unparalleled intellectual grasp of contemporary political and economic culture is always a delight to encounter. Mishra writes with erudition, clarity, and deep humanity, and doesn’t shy away from satisfyingly targeted polemics that call out shallow thinking in service of power. But apparently he’s also a novelist? Run and Hide is Mishra’s first work of full-length fiction in 20 years, and tells the story of three friends who rise from humble origins—and the vaunted classrooms of the Indian Institute of Technology—to claim a seat at the global tech table, along with all the money, prestige, and jetsetting hubris that comes with it. –JD

Harvey Fierstein, I Was Better Last Night

Knopf, March 1

This memoir by the four-time Tony Award-winning actor and playwright, gay rights activist, and all-round cultural icon (whose inimitable voice was once memorably compared to that of “a deep-throated jazz diva who has just tossed back a double-bourbon”) is sure to be an absolute delight, as well as a fascinating window into the gay rights movement of the 70s and 80s and the New York theater scene of the past four decades. “I never thought I’d spill my guts but, when COVID locked me in with my computer, I figured I’d amuse myself and give this a try,” Fierstein said of I Was Better Last Night. “Well, here is the outrageous, juicy, scary, and mostly true result of my efforts.” Audiobook strongly recommended. –DS

Lee Cole, Groundskeeping

Knopf, March 1

As someone constantly awaiting the next great campus novel, I am already counting the days until debut. Cole’s campus denizens are the classic writer in residence, Alma, and less classically: the groundskeeper, Owen. They are similar in some ways—they both write, and are obsessed with the craft and the story of their lives—but different in almost every other way: class, political upbringing, education. What could go wrong? –JH

Sarah Polley, Run Towards the Danger: Confrontations with a Body of Memory

Penguin Press, March 1

Sarah Polley’s autobiographical documentary, The Stories We Tell, is one of my favorite works of art, in any medium. And now, in an era when we all seem to be revealing ourselves, all the time, via an endless shallow stream of digital ephemera, the depth of Polley’s 2012 cinematic memoir is even more of a revelation. So I am eager to dig into Run Towards the Danger, a collection of six essays that promise to “capture a piece of Polley’s life as she remembers it, while at the same time examining the fallibility of memory, the mutability of reality in the mind, and the possibility of experiencing the past anew, as the person she is now but was not then.” –JD

Warsan Shire, Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head

Random House Trade Paperbacks, March 1

This full-length collection of poetry by Somali British poet Warsan Shire depicts a journey to womanhood intermixed with pop culture and news references. Shire’s body of work has always impressed me with its triumph of visceral, biting imagery. Known for her contributions to Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade and Black Is King, Shire uses language to shape loneliness into wise phantoms and transform heartbreak into blood, muscle, and bone. It’s evident in earlier poems like “The House,” wherein women are sanctuaries under siege and men are brute practitioners of ultraviolence. Shire’s poetry flows with power like the earth splitting wide open. –VW

Claire Louise Bennett, Checkout 19

Riverhead, March 1

This is an easy one: Checkout 19, recently published in the UK, has already seen its fair share of rave reviews. Just as with Bennett’s Pond, don’t expect a linear story, but do expect ramblings, musings, interiority, and the poetry of thought, even on mundanity. Bennett has the superb ability to capture the reality of a mind: it is rare to think in fully formed, conclusion-ridden ideas, after all. Our brains are often a maze, and we find ourselves repeating, circling, ending up somewhere we didn’t mean to go. Checkout 19 is a fresh take on the coming-of-age novel—one in which we don’t already know how the story will end, or if it will have an “ending” at all. Bennett manages to convince the reader that somewhere, her narrator continues to think and ponder and live and wrestle with being in a body, like the rest of us. –JH

Sarah Moss, The Fell

FSG, March 1

If you’ve read Ghost Wall and Summerwater, you know a Sarah Moss book when you see it! There is always the electric touch of danger lacing its fingers through the story. In this particular tale, a woman is confined to her house for a mandatory quarantine. It’s a suffocating situation we can all relate to. So, she sneaks out for a walk. No one has to know! But as the title implies, she slips and falls. There she lies: injured, vulnerable, at the mercy of those around her. It’s the end of the world, seen from a particular angle only the incisive Sarah Moss could show us. And if you’re wondering why you should read another book about the pandemic that you are still living through, it’s because there is a good dose of humor and humanity in these pages, too. –KY

Meghan O’Rourke, The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness

Riverhead, March 1

Megan O’Rourke’s nearly decade-long investigation into chronic illness is part memoir, part journalism, filled with interviews with doctors, patients, researchers, and public health experts. The Invisible Kingdom takes the question of how we treat hard-to-understand medical conditions and argues for a reimagining of how we understand our bodies and our relationship to our health. O’Rourke is a poet above all else, and it’s with incredible, lyrical empathy that she not only shares her own story of and eventual diagnosis with late-stage Lyme disease, but puts it in perspective of an entire generation of patients who’ve been dismissed: “It is a truth universally acknowledged among the chronically ill that a young woman in possession of vague symptoms… will be in search of a doctor who believes she is actually sick.” A must read. –EF

Kathryn Davis, Aurelia, Aurélia

Graywolf, March 1

Kathryn Davis’ first memoir is recognizably hers—place-based, with hints of magical realism, about journeys, movement—but is by necessity much more personal than her fiction. She writes about being a teenager, trying on identities like clothes, and about being in late middle age, resolutely someone, and yet still wondering, still trying on the other clothes, even while liking her own. At the memoir’s center is the death of her husband, and her reflections about the life they lived together. By turns grieving and joyful, the book explores the pivotal crossroads in her life, and takes us along as she continues the journey. –JH

Gu Byeong-Mo, tr. Chi-Young Kim, The Old Woman with the Knife

Hanover Square Press, March 1

A sixty-five-year-old female assassin, need I say more? Byeong-Mo’s novel follows Hornclaw, the aforementioned female assassin who finds herself on the cusp (or rather, the expectation) of retirement. But when an injury leads her to a doctor and his family, her own feelings and emotions come up to the surface, and with them, a new kind of stake. The Old Woman with the Knife, Byeong-Mo’s first novel to be translated into English from Korean, is sardonic and funny, as it probes at the expectations around aging women and their bodies. –SK

Negesti Kaudo, Ripe

Mad Creek, March 2

A debut essay collection from an exciting new voice, Negesti Kaudo’s Ripe probes topics of race, class, sexuality, and more through cultural criticism and her experiences as a young Black woman in the Midwest. It joins the ranks of other recent collections on intersectionality such as Hood Feminism and Against White Feminism, a must-read contemporary canon. –ES

NoViolet Bulawayo, Glory

Viking, March 8

In 2013, NoViolet Bulawayo took the world by storm with her incredible debut, We Need New Names. (It has been argued that that book is actually one of the best debuts of the decade, a sentiment that I wholeheartedly agree with.) Now, the Booker-prize finalist is back. Glory is set in a fictional place, at a familiar time of turmoil. Inspired by the 2017 coup that saw the fall of Zimbabwe’s president, Glory starts with the dethroning of Old Horse, a leader no more. Through the voices of the animal kingdom, we are shown a nation on the precipice. NoViolet Bulawayo has an unmatched ability to enchant the trials and tribulations of life lived in a nation in turmoil. In the past, she has done this through the eyes of the children. In this one, through animals. Like all good allegories, Glory is sure to be an impressive feat of imagination and a haunting reflection of reality. –KY

Matt Bell, Refuse to Be Done

Soho Press, March 8

The subtitle of this one—”How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts”—is about as compelling a pitch as I can imagine. I struggle mightily with revision, so I’m excited to read Bell’s “encouraging and intensely practical” craft book. –JG

Maayan Eitan, Love

Penguin Press, March 8

Maayan Eitan’s debut follows Libby, a young sex worker looking for, yes, love. Through a series of short fragments, Libby tests out different narratives about her life and past. Last year, Love was a “literary sensation in Israel”; let’s see what it does here. –WC

Tara Isabella Burton, The World Cannot Give

Simon & Schuster, March 8

Burton’s second novel is just as deliciously involving as her debut Social Creature, but makes rather better use of her doctorate in theology and ongoing religious scholarship. It is set at a tiny academy in Maine, where a sensitive teenager obsessed with an obscure novel—whose author, a student at the school, died at 19—falls in with a cultish church choir of boys, led by the brutal and neurotic Virginia. It’s a book about the nature of and limits of fervor, religious, sexual, and otherwise, and a spellbinding coming of age story that—despite being set in the Instagram-laden present—feels somehow plucked out of time. –ET

Stewart O’Nan, Ocean State

Grove, March 8

This is a book about murder, but it is not a mystery. Well, there’s mystery, but not in the whodunnit sense. In the first line we are told who died, and who killed them; what expands from that immediate reveal is the slow unraveling of why. The story centers on the killer and her family, her mother, her sister, and all the tangled lives and actions that one by one, add up to the final tragedy. This is a beautiful, devastating novel of family and young love, and unredeemable acts. –JH

Christopher Kempf, Craft Class: The Writing Workshop in American Culture

Johns Hopkins University Press, March 15

As of 2016, there are over 350 creative writing MFA programs in the U.S.; 40 years prior, there were only 52. Nearly all operate on the workshop model. Poet Christopher Kempf places the idea of the artisanal workshop in its capitalist historical context, taking the craft/labor metaphor as its central question: in the “workshop,” what type of work is being done? And what are the contradictions that arise when writing, like other artisanal goods, is evaluated as both labor and not-labor? Worthwhile if you’re a creative writer—or reader. –WC

Melissa Febos, Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

Catapult, March 15

If I could do cartwheels, I would have cartwheeled across the room when I learned that the brilliant Melissa Febos is gifting us with a memoir craft book. One of my all-time favorite writers and thinkers, Febos draws on her own life trajectory to discuss matters of so-called navel-gazing, writing about others, and “the power of divulgence.” I can’t wait to dive in to this one. –ES

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, In the Margins

Europa Editions, March 15

There is so much mystery shrouding the beloved Italian author, Elena Ferrante. For years, readers and scholars have gone on some deep dives, trying to pinpoint the writer’s identity. If you, too, have wondered who exactly penned My Brilliant Friend, hopefully it comes from a place of deep admiration. The latest book from Elena Ferrante, translated by Anne Goldstein, is sure to answer some of your questions. Who is Elena Ferrante as a reader? As a fellow writer, struggling against the page? Who have been her influences? In the Margins is that rare peek inside the lively mind of one of our most influential writers working today. –KY

Eloghosa Osunde, Vagabonds!: A Novel

Riverhead, March 15

Plimpton Prize winner and consistently thought-provoking Paris Review columnist Eloghosa Osunde’s debut novel catalogues the lives of an ensemble cast of vagabonds, “for whom life itself is a form of resistance,” before bringing them all together for the event of a lifetime. Said Osunde, writing Vagabonds! “relocated [her] to a place where imagination meets courage.” –WC

María Gainza, tr. Thomas Bunstead, Portrait of an Unknown Lady

Catapult, March 22

Gainza’s Optic Nerve was one of my favorite novels of 2019 (when it was first published in English), so I’ve been anxiously awaiting this follow-up. Like Optic Nerve, Portrait of an Unknown Lady is intelligent and tensile, if mostly plotless, taking place in the world of art and those who both appreciate and make it, though here the narrator is not tracing her own life through art, but rather the life of a famous (or infamous) Argentinean counterfeiter, the truth of whom eludes her. She interviews acquaintances, sifts through court records, and even reproduces an auction catalogue; the result is a loose investigation into the nature of art and of memory, scattered with gems of intrigue and insight. –ET

Alejandro Varela, The Town of Babylon

Astra House, March 22

It’s hard to imagine a scene riper for drama and psychological exploration than a twenty-year high school reunion: that’s where we find protagonist Andrés, a professor, in The Town of Babylon, Alejandro Varela’s debut novel. As Andrés reckons with figures from his past, his story also becomes an inquiry into the ways that queerness, race, and class affect the course of one’s life. –CS

Colm Tóibín, Vinegar Hill: Poems

Beacon Hill Press, March 22

Tóibín’s collection of poems rests at the wedge between the private and the public. Whether it be queer love or COVID or religion, whether they move through Dublin or Venice or Enniscorthy, Tóibín situates his poems at an interstice, lacing them with threads of both humor and emotion. Written over the course of many decades, his first poetry collection is an extension of the themes of his novels, explored via the malleability of verse. –SK

Candice Wuehle, Monarch

Soft Skull, March 22

Wuehle has published three poetry collections, and as a sucker for a poet novel, this is a major selling point for me. Her debut novel “merges iconic true crime stories of the ’90s (Lorena Bobbitt, Nicole Brown Simpson, and JonBenét Ramsey) with theories of human consciousness, folklore, and a perennial cultural fixation with dead girls.” Sold. –JG

Amanda Oliver, Overdue: Reckoning with the Public Library

Chicago Review Press, March 22

Part memoir, part ode, part indictment, Overdue is the firsthand story of Amanda Oliver’s life as librarian, starting with her first day on the job as an eager young professional in an underserved neighborhood in Washington, DC. What Oliver slowly discovers is that—despite the fact they do indeed offer hope and opportunity to so many who wouldn’t otherwise have it—libraries nonetheless mirror all of the deep systemic problems contained in American society. How can libraries repair their own institutional fault lines around racism and economic oppression, wonders Oliver. How can libraries survive America? –JD

Maud Newton, Ancestor Trouble

Random House, March 29

In her new memoir, Maud Newton plumbs the depths of the multibillion-dollar industry of ancestral research in an effort to make sense of her own family history, which is peppered with stories both bizarre and traumatic. Newton doesn’t avoid the sins of her kin—including their involvement in slavery and genocide—in this intricately researched account of the most universal subject. –ES

David Shields, The Very Last Interview

NYRB, March 29

It’s been a dozen years since Shields published Reality Hunger, his controversial “manifesto” of the literary remix, which I first loved, and then pooh-poohed, and then sort of loved again, but regardless have continued to think about ever since. This new book is a return to the Reality Hunger energy: the portrait of a writer as an interview subject, made up of the thousands of questions Shields has been asked over the last twenty-five years—reorganized, rewritten, and with their answers entirely omitted. The result is sometimes annoying, sometimes funny, sometimes existentially provoking—like a self-deprecating Lyn Hejinian’s My Life for writers. –ET

Megan Mayhew Bergman, How Strange a Season: Fiction

Scribner, March 29

Megan Mayhew Bergman is one of the best authors out there for chronicling our tangled, intimate, complicated relationship to the natural world; her elegant, lyrical prose documents an evolving crisis and our incorrigibly human responses to it. She’s published widely on the climate crisis for outlets including The Guardian and The Paris Review in addition to authoring Almost Famous Women and Birds of a Lesser Paradise, among the rest of her extensive work. Now, I’m eagerly awaiting her new collection—consisting of short stories and a novella—which features characters as they navigate landscapes natural and emotional and reckon with the echoes of history in their daily lives. –CS

APRIL

Gayl Jones, Song for Almeyda and Song for Anninho

Beacon, April 5

This year has seen renewed interest in Gayl Jones, whose novels were first published in the mid-1970s to critical acclaim. Toni Morrison was an advocate of Jones and praised the manuscript of 1975’s Corregidora: “No novel about any black woman could ever be the same after this.” Yet Jones disappeared from the public eye in 1998—why? Perhaps that answer is not as important as why Jones’s work is considered a touchstone of Black American literature. This volume of poetry, set in the late 17th century, revisits the characters introduced in Palmares—Almeyda and Anninho. This decolonial love story in verse adds to the impressive oeuvre of Jones. –VW

Jennifer Egan, The Candy House

Scribner, April 5

Fans of A Visit to the Goon Squad (me) will not be disappointed by this “sibling novel,” in which Egan returns to the structure (interconnected but discrete sections in an impressive variety of styles—tweets instead of PowerPoint this time) and some of the characters of her Pulitzer Prize winning 2011 novel. In fact, she justifies her form even further here—many of the sections touch on the consequences of a new tech innovation, “Own Your Unconscious,” which allows users (i.e. everyone) to export their experiences and then (of course) upload them to the cloud for all to share. But more interesting—and this, really, is Egan’s point—is the humanity of this novel, the way in our lives, too, are interconnected but discrete, and how they fit together. It is very good. –ET

Ludwig Wittgenstein, tr. Marjorie Perloff, Private Notebooks

Liveright, April 5

Initially written in code during WWI and translated for the first time in English by Perloff, Wittgenstein notebooks contextualize the early years of his Tractatus-Logico-Philosophicus. Starting with the summer of 1914, when Wittgenstein finds himself a soldier in the Austrian army, the notebooks consider his sexuality and explore the formations of analytical philosophy, as they pertain to the looming instances and potential of death of the early 20th century. –SK

Sara Nović, True Biz

Random House, April 5

“True biz” is an exclamation in American Sign Language: really, seriously, definitely, real-talk. Novic’s second novel is a coming of age story set at the River Valley School for the Deaf, where students Austen and Charlie, and CODA (child of deaf adults) headmistress February learn to navigate their place in the world. With a television adaptation optioned, this is an incredible story of sign language, disability rights, first love, and loss. –EF

Chelsea Bieker, Heartbroke: Stories

Catapult, April 5

If you haven’t yet read Chelsea Bieker’s Godshot, you have a few months to do so before her debut story collection hits. If you have read her cult classic (wink wink), and you’re still thinking about it, you’re in luck. The characters you will encounter in Heartbroke are sure to be just as unforgettable. Set against the backdrop of sunny California, in these stories, you will encounter: teenagers flirting with danger, an entrepreneurial mother–son duo, a phone sex operator, a very sad kidnapper. Chelsea Bieker is back, baby! –KY

Emily St. John Mandel, Sea of Tranquility

Knopf, April 5

Readers of Mandel’s Station Eleven and The Glass Hotel will not be disappointed by her latest, a generous and elegant novel about art and family and time travel—in fact, they will be particularly rewarded by the way the three texts intersect. I won’t say more about that, except to note that it was a strange experience, reading this book in a pandemic—certain passages made me shudder, but others gave me solace. After all, no matter what happens, time, at least as Mandel sees it, will go on. –ET

Chloé Cooper Jones, Easy Beauty

Avid Reader Press, April 5

This memoir about disability and motherhood spans the globe – from “life in Brooklyn to sculpture gardens in Rome; from film festivals in Utah to a Beyoncé concert in Milan; from a tennis tournament in California to the Killing Fields of Phnom Penh.” Cooper Jones challenges the unspoken social taboos about the disabled body, unpacking myths of beauty and our complicity in upholding those myths. Blending journalism, philosophy, and memoir, it’s a book that everyone will be talking about this Spring. –EF

Lisa Russ Spaar, Paradise Close

Persea, April 5

It seems like all of of my favorite novelists are also poets, and so as an enormous fan of Lisa Russ Spaar’s lush, ecstatic poetry, I can’t wait to read her first (!) novel, a book about outcasts and exiles that Eleanor Henderson described as “a soulful, sexy, extraordinarily lyrical meditation on things that matter―art, aging, love, desire, the body, and the brief, passionate encounters that bind us to each other and sometimes save our lives.” Perfect, I suspect, for reading in the garden this season. –ET

Ocean Vuong, Time Is a Mother

Penguin Press, April 5

When Night Sky With Exit Wounds came out over five years ago, it was a revelation. When On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous hit shelves two years after that, it was every bit as breathtaking. All of Ocean Vuong’s writing shows a masterful attention to detail. He comes at language with a magnifying glass. He holds words differently than everyone else, and when he hands them to you, they are changed. Now Ocean Vuong returns to poetry with his second collection. Dealing with the death of his mother, this new book comes from a place of grief and memory, turning loss over and over in a way that only this writer can. You’ll want to read this latest addition to his oeuvre immediately. –KY

Douglas Stuart, Young Mungo

Grove, April 5

Booker-prize winner Douglas Stuart’s second novel is another a vivid story of working-class Glaswegian life. The emotional and suspenseful story follows two young men, Mungo and James, as they fall in love against all odds, amidst hypermasculinity, violence, and sectarianism. Stuart’s debut, Shuggie Bain, was universally loved; a heart-wrenching story of a young boy and his alcoholic mother. Young Mungo promises to be as unforgettable and powerful, revealing the violence faced by many queer people, and the dangers of loving someone too much. –EF

Jeff Deutsch, In Praise of Good Bookstores

Princeton University Press, April 5

As though it hadn’t already hooked you from the title, In Praise of Good Bookstores is also written by Jeff Deutsch, director of the well-beloved Seminary Co-op Bookstores in Chicago—the first not-for-profit bookstore in the US and one renowned for its unique collection of academic titles. Deutsch ties his love of bookstores, reading, and knowledge to Jewish traditions of education and reflection, which also resonates with the rich literary tradition that Jewish writers developed in Chicago during the early and mid-20th century. If you’re still reading this blurb, by far the nerdiest one I’ve ever written, then we should both read this book. –CS

Samantha Hunt, The Unwritten Book: An Investigation

FSG, April 5

The Dark Dark pushed the boundaries of what one could do with short fiction, so I’m particularly excited to check out Samantha Hunt’s first foray into nonfiction. Well, a “genre-bending work of nonfiction,” but we should expect nothing less. In The Unwritten Book, books = ghosts. Reading is a way of talking to the dead. Remembering stories is a way of being haunted by them. Fuelled by the discovery of her father’s unfinished manuscript, Samantha Hunt is on the hunt (sorry) for clues about all that is left unsaid. Part literary criticism, part memoir, part family history, this new book explores the things that have a hold on us. I, for one, am ready to be haunted by Samantha Hunt once again. –KY

Jenny Tinghui Zhang, Four Treasures of the Sky

Flatiron, April 5

In Zhang’s debut novel, set in the American West of the 1880s but shot through with Chinese folklore and calligraphic references, a 13-year-old girl is kidnapped from a Chinese market and brought to San Francisco. Under the shadow of the Chinese Exclusion Act, she makes her way to Idaho, passing as a boy to survive, but hoping, despite everything, to do more than that. –ET

Claire Kohda, Woman, Eating

HarperVia, April 12

You might think the time for vampire novels has come and gone, but you clearly wouldn’t be imagining this one. Woman, Eating is about the every-girl: Lydia scrolls on Instagram, loves Buffy the Vampire Slayer, likes to paint, misses her mom, has a crush on a cute boy—and she’s hungry. Boy, is she hungry. But even though the food she craves is the food we crave: sushi, ramen, ice cream, cake, the only food she can ingest is blood. Why? Because she’s a vampire, of course, just not your typical version. Lydia is overwhelmed with the same thoughts that plague the normal human—about identity, her father’s race and culture and what it means for her, how to be, how to live—and yet to top it all off she has to deal with the whole question of eating. Can she have it both ways? –JH

Gary Indiana, Fire Season: Selected Essays, 1984-2021

Seven Stories Press, April 12

Even if you don’t agree with him, the iconic Gary Indiana is always worth your time. This collection of his essays contains, as the publisher puts it “sometimes bitchy, always generous, erudite, and joyful assessments from the last thirty-five years of cutting-edge film, art, and literature.” Sounds about right. –ET

Margo Jefferson, Constructing a Nervous System

Pantheon, April 12

Jefferson (Negroland) excavates inner truths in this memoir about pivotal life moments. Using the structure of a nervous system as a framework, Jefferson approaches the subject of physicality as a state of wonderment. The book’s approach to storytelling is surprising and refreshing, allowing Jefferson to experiment with literary convention. Our identities are often comprised of our responses to the world around us; art and other forms of creative expression can serve as blueprints for transcendence. I look forward to seeing how Jefferson is able to unify—or rather fuse divergent fragments—into a body of kinetic energy. –VW

Mary Laura Philpott, Bomb Shelter: Love, Time, and Other Explosives

Atria, April 12

“If this happened, what else could?” The thought first arrives when historically sunny, glass-half-full Philpott finds her teenage son unconscious in his room. This world-shaking event forces Philpott to reorganize everything, including her own thoughts and her relationship to faith. In this memoir in essays, “If this happened, what else could?” becomes a refrain. But ultimately, Bomb Shelter serves as a kind of balm: While recognizing the unpredictable, the random, unstoppable forces of life, Philpott gently guides the reader with humor and familiarity through life’s terrain, letting her readers know if she can do it, we can do it. –JH

Leigh Newman, Nobody Gets Out Alive: Stories

Scribner, April 12

In these stories, all set in Newman’s home state of Alaska, women seek survival, connection, home and safety, their quests tinged with the wildness of the state, the unknowability of the landscape, as well as the male-dominated culture that’s prevailed there for decades. The tales span the last century, some taking place in the Last Frontier, some in the early years of the 20th century; all are stunningly crafted, and make it impossible to think of moving on to the next story and leaving behind the character in question, until you do, and find that each is better than the last. –JH

Tajja Isen, Some of My Best Friends

Atria/One Signal, April 19

Catapult editor Tajja Isen is ready to call everyone on their bullshit. If liberal industries can call out institutionalized racism, why can’t we actually change it? Blending inviting personal essay with biting cultural critique, Some of My Best Friends takes readers to the uncomfortable space between what Nice White People intend and the inaction rooted in our society. These essays explore the problems of representation in Hollywood, the blinding whiteness of the literary industry, and band-aids companies attempt to stick to the wound. It’s time to rip the band-aid off. It’s time to read Tajja Isen and dare to dream of a better place. –KY

Tove Ditlevsen, tr. Michael Favala Goldman, The Trouble with Happiness: And Other Stories

FSG, April 19

Last year’s best book of the year (according to The New York Times and me) was Tove Ditlevsen’s Copenhagen Trilogy. Now her short stories are available for the first time in English. These “poignant and understated stories” have the same pared down voice and incredible authority of the memoir (and, according to her translator, these stories sometimes mine her own life for material, with some stories appearing “to be extrapolations of scenes that are mentioned only briefly in her memoirs.”) You can read one of the stories, “The Umbrella,” that was published in The New Yorker, and grab the rest in April! –EF

Louisa Lim, Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong

Riverhead, April 19

Lim’s book, covering the key moments in Hong Kong’s history—from the 1842 British colonization to the 1997 British-Chinese negotiations—centers Hong Kong in its own narrative, highlighting guerilla calligraphers, amateur historians, and street artists who make up the place. At the heart of it is the King of Kowloon, the street artist whose work shapes and is shaped by the larger identity of Hong Kong, from being unseen to seen, unheard to heard. –SK

Adrienne Celt, End of the World House

Simon & Schuster, April 19

Best friends go to Paris at the end of the world—which sounds good to me already, but then you discover that the end of the world turns out to be resisting itself . . . by means of a time loop. I suppose you could be in worse places for eternity than the Louvre, but I’ll still be reading to find out what happens. –ET

Thomas Piketty, A Brief History of Equality

Belknap Press, April 19

I am sure much smarter people than me are poised to consider this book—which is, as the title suggests, a précis of Piketty’s full body of work around the subject of equality, and its evil twin, inequality—in conversation with David Wengrow and the late David Graeber’s riotously fun The Dawn of Everything. Though they arrive at it through different means and modes of scholarship, Piketty and the Davids seem to come to the same conclusion: “Guys, wtf, it doesn’t actually have to be like this.” To which I say, YES. –JD

Kris Manjapra, Black Ghost of Empire: The Long Death of Slavery and the Failure of Emancipation

Scribner, April 19

Manjapra’s book traces the unfinished work and process of emancipation in the Atlantic world. Highlighting the movements that began in the 1770s and and ended in the 1880s, Manjapra examines the Gradual Emancipations of North America, the Revolutionary Emancipation of Haiti, the Compensated Emancipations of European overseas empires, the War Emancipation of the American South, and the Conquest Emancipations of sub-Saharan Africa, in order to investigate the ways in which such abolition processes ultimately sanctioned violence against Black communities and affirmed white supremacy. In the context of these unfinished processes, Manjapra considers the ways in which grassroots Black activists have become the stewards of care and recovery, for both the past and the present. –SK

Steve Almond, All the Secrets of the World

Zando, April 19

I still remember reading “Donkey Greedy, Donkey Gets Punched” in the Best American Short Stories 2010 as a child, and being stunned by its use of graphics (now, I’d be stunned by other elements). Now, over a decade and many short stories (and nonfiction works) later, Steve Almond is finally releasing his debut novel. In it, two girls are paired together for the science fair, setting off a chain reaction that sends one of them through the desert and into the criminal justice system. Zando says the book is Little Fires Everywhere meets Breaking Bad—that can’t be boring. –WC

Shuang Xuetao, tr. Jeremy Tiang, Rouge Street: Three Novellas

Metropolitan Books, April 19

This collection of three novellas moves readers from an inventor of dreams to a criminal stuck under a frozen lake to a strange, strange girl. Set in Shenyang, a post-industrial city in the northeast of China, Xuetao’s novellas are as beautifully frigid and gritty as the city he writes about, as he inspects the dust left following an economic boom, and the things that percolate in spite of lost and unfulfilled promise. –SK

Kim Kelly, Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor

Atria/One Signal Publishers, April 26

I first became aware of Kim Kelly due to her excellent reportage as a labor columnist for Teen Vogue. In Fight Like Hell, Kelly promises the same type of hard-hitting, nuanced coverage we’ve become accustomed to. Kelly’s coverage of the history of the American labor movement doesn’t rely on the whitewashed, oft-repeated narratives that populate the pages of school textbooks. –VW

Robert M. Pirsig, ed. Wendy K. Pirsig, On Quality: An Inquiry into Excellence: Unpublished and Selected Writings

Custom House, April 26

Attention all Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance acolytes (or ex-acolytes): the unpublished writings of Robert M. Pirsig, who died in 2017, will soon be available for public consumption, thanks to the efforts of Wendy K. Pirsig, the author’s wife of 40 years, who edits and introduces the collection. Will 2022 be the year that MOQ comes back? Only time will tell. –ET

Viola Davis, Finding Me

HarperOne, April 26

From How to Get Away with Murder to Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, you’ve seen Viola Davis. You know Viola Davis. But do you really? One of six children, daughter to an alcoholic/horse trainer and a factory worker/civil rights activist, Viola Davis grew up in poverty in South Carolina and Rhode Island. Finding Me takes us from the hardships of those early days to the possibilities of stage. When asked by Oprah Daily what inspired her to write this book, she said, “It’s my way of helping people feel less alone in a world that’s so isolating.” What better reason than that? –KY

Sara Baume, Seven Steeples

Mariner Books, April 26

The second book from the author of Spill Simmer Falter Wither is a lyrical meditation on nature and companionship, following two people who give up on their disappointing, conventional lives, and retreat from everything, disappearing into the Irish countryside. As the kids say: goals. –ET

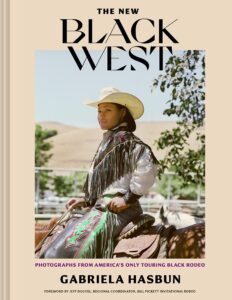

Gabriela Hasbun, The New Black West: Photographs from America’s Only Touring Black Rodeo

Chronicle Books, April 26

For years photographer Gabriela Hasbun has been documenting the annual Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo in the hills outside Oakland, which brings together a community of Black cowboys whose very existence flies in the face of America’s old myths of the West. Hasbun’s beautiful photographs of contemporary Black rodeo riders—and their families, their celebrations—honor a rich legacy too often ignored by the wider world. –JD

MAY

Vauhini Vara, The Immortal King Rao

W.W. Norton, May 3

Vauhini Vara’s debut novel follows Athena, a young woman accused of killing her father—a tech mogul who grew up on a Dalit plantation and became the most powerful person on earth through the force of his corporate-led government. The book grapples with the effects of capitalism as well as technological development on politics, families, and memory itself, and it seems sure to be an engrossing read. –CS

Lillian Fishman, Acts of Service

Hogarth, May 3

By May, we’re going to be in dire need of some sexy fiction (birds, bees, long Covid winter, etc.) and this is the debut to which I shall turn. It’s picking up all the right comparisons—Sally Rooney, Ottessa Moshfegh, Joan Didion—and the right blurbs—Raven Leilani, Gary Shteyngart, Sheila Heti—but it’s actually Edmund White’s endorsement that has me the most curious: “This fascinating novel, which will be read as a defense of libertinism, paradoxically turns out to be a book of exquisite moral refinement and almost intimidating elegance,” he writes. Clearly I will be reading that. –ET

Renee Gladman, Plans for Sentences

Wave Books, May 3

Text and drawing, drawing and text all collapse into one another in Gladman’s new interdisciplinary collection. Pushing the boundaries of the visual and the textual, Gladman considers the ways in which the two practices can invent and reinvent one another, offering a limitless and circular plunge into the idea of poetry. Indeed, like most of her work, language feels endless and infinite, lingering even after we put the book back on the shelf. –SK

Courtney Maum, The Year of the Horses: A Memoir

Tin House, May 3