Interview With a Gatekeeper: Nan Talese

From Random House's First Female Literary Editor to Her Own Imprint

Nan Talese, arbiter of her own imprint at Knopf Doubleday, loves books. And when she’s enthusiastic about one, she will publish it, despite an almost unfavorable profit and loss analysis. Her sweet but persistent approach to almost everything is rooted in her Texan heritage and her New York upbringing, a fierce combination that grants her an uncompromising approach to the written word. But her generosity exceeds her unflappability. We talk for three hours under the shade of old trees at her simple, rural Connecticut home, a place she prefers to be much of the time, a place she bought without telling her husband, the writer Gay Talese. “Would you like to borrow a bathing suit?” she asks, pointing to her pool while her dogs bark at the tractor grading the driveway of the Episcopal Church next door. After my interview, I leave with an armful of books she insists I read and plans to get together again, as we are neighbors in this close-knit town.

Kerri Arsenault: How did you come to editing?

Nan Talese: I was working at Vogue and Gay and I were dating. He said to me, You read all the time, so maybe you should go talk to Random House; an editor there wants me to write a book, but I don’t think I will right now. So I went to Random House and was introduced to the Editor-in-Chief. He gave me a piece of paper with typing on it and said, find all the errors in it—and I did. I gave it back to him and they offered me a job.

KA: I’m not sure that could happen now.

NT: [Laughs] About six months later the Editor-in-Chief said, There were lots of errors on that piece of paper and you caught every single one, except for one where there should have been a new paragraph. He said, You didn’t catch that, but everything else you caught.

KA: What were you doing at Vogue at that time?

NT: I was the Assistant to the Accessories Editor. I would go on photo shoots and bring white kid gloves, and pearls…But, after Vogue, I couldn’t believe Random House was paying me to read because it was so wonderful.

KA: Were you just given manuscripts to edit from the very start?

NT: No. I started proofreading the galleys, which I did and caught some editing mistakes in them. Then they asked me to copy edit, and I did that. The Editor-in-Chief, who was Robert Penn Warren’s editor, said Warren has just turned in a book; he liked your copyediting on the last book so would you edit this novel? So I did! I remember thinking, Robert Penn Warren! I would ask him things like, is that the right word? Is that what you really mean? I thought, here I am questioning the author of Brother to Dragons and All the King’s Men. Anyway, at one point I remember saying, Mr. Warren could you introduce this character here because we really don’t know who he is? He said, well, actually I introduced him in chapter two but I didn’t do it well enough if you don’t remember him; so I should either reintroduce him here or make a stronger impression on the reader at the beginning. I learned so much from working with him, and it taught me to always ask questions.

KA: That’s what a good editor does.

NT: Yes. Soon after that, I was called up to Bennett Cerf’s office, he was one of the founders of Random House, and he said they had a manuscript for me to look at, a book by A.E. Hotchner about a summer in Spain with Ernest Hemingway. Bennett said, Would you read it? And I said, yes, and I took it down to my basement office and read it. Then they asked if I would come up to his office and talk about it—at the time, all the editors were men. They asked, What do you think about Hotchner revealing that Hemingway committed suicide? And I said, I think it’s just fine even though it was only rumored at that time. Hotchner came in about a week later and they called me upstairs again. (Hotch told me later he thought I was going to bring everybody coffee). They introduced me as the editor. Hotch was sort of surprised because I looked very young. We went down to my basement office and got to work. I would say to him, That’s not very interesting, would you cut that? We ended up cutting a fifth of the manuscript and he added a fifth.

KA: Obviously you kept the better fifth.

NT: It became a bestseller. And it was excerpted in Life magazine, which was a big deal then, and it also became a Book-of-the-Month club selection.

KA: So you were on your way.

NT: I was just a reader!

KA: But a good one.

NT: Well, I had read a great deal. But I didn’t read much when I was young. I was very social. I went out to the Stork Club and parties and dances. I only realized later on that I didn’t like the social world. Having a book with me protected me from other people. I was once asked, what would it require for a person to come work for me and I said all I want to know is what they’ve read. They’d ask, any degrees? And I said, No, I didn’t care about that. I cared about what they read.

KA: You were the only woman working at Random House at when you began your career?

NT: Of literary work. Women were editors of cookbooks and children’s books.

KA: How was that?

NT: You know I didn’t think about it. Not exactly. The first year we had our first child but I could even edit in the hospital. I acquired the books of lesser known writers and worked with them.

KA: Were you ever a writer yourself?

NT: No. In fact, when I have to write letters to authors I always get really tense.

KA: Why?

NT: Because they are the masters of language and I am not.

KA: What books are you looking at now?

NT: There’s one I think is really good. It’s about modern morality and ethics and and it’s very complicated. I’m going to publish it next summer; it is called Behaving Badly, by Eden Collinsworth about morality in sex, business, and politics.

KA: You must be taking your cues from today’s papers.

NT: You know, I was reading the Times this morning and thought, I can’t believe anything that’s in the paper today. Who’s right and who’s wrong? It’s hard to know. Sometimes the news on the Internet may be so inaccurate it is hard to believe.

KA: So you’re sticking to good literature instead.

NT: Yes, I’m sticking to acquiring good literature. It might not sell, but happily, the president of Knopf Doubleday likes what I do.

KA: I’ve been talking to editors about what they acquire, about what attracts them to a book.

NT: Who have you spoken to?

KA: Lee Boudreaux, Rebecca Saletan, Elisabeth Schmitz, Jeff Shotts, Declan Spring, Michael Weigers…

NT: Well, those editors are all splendid. What you ought to do is look at the commercial bestsellers and talk to some of those editors.

KA: Do you think more commercial books subsidize less commercial books?

NT: In the short run, yes but take Ian McEwan. He probably won’t earn back his advance immediately on Nutshell but it will sell year after year. Or the book I’m publishing by Simon Tolkien, the grandson of JRR Tolkien, called No Man’s Land, which is about the Battle of the Somme; they are such fantastic books! But I also have published Margaret Atwood for 37 years, and she has a real following.

KA: She’s also followed you from publisher to publisher.

NT: Yes. I went from Random House to Simon & Schuster to Houghton Mifflin, and now I’m at Knopf Doubleday. I didn’t want to leave Houghton Mifflin but Doubleday said, why don’t you have your own imprint? That was in 1990. And my authors followed me. Also, when I was at Houghton Mifflin, the Director asked if I would like to publish Pat Conroy. I didn’t know Conroy’s work but I said, yes, fine, and I got this 1,500-page manuscript from him! A friend of his kept seeing Gay and me at Elaine’s restaurant and kept saying, Pat wants to know what you think? I said, well if he sent me 300 pages I could tell him. I remember writing in the margin of that manuscript, “this should be 485 pages earlier.” Finally, I made a six-page graph. [she draws with her finger] I wrote here is the timeline, and the present time was across, and the arrow going backward was a flashback, and a double arrow going backward was a double flashback. I filled up six yellow pages with that graph. When Pat came in to meet me he was very nervous as was I, but he said, nobody’s ever read my work so carefully! That book was The Prince of Tides, and from then on I was his editor for all his other books. Before I left Houghton Mifflin, I signed a contract for Conroy’s next two books. Pat said, I want to follow you. And I said, you signed a perfectly good contract with Houghton Mifflin and you have to honor that. And he said, well, I won’t write then. Eventually, he said to Houghton Mifflin, if you don’t let me go, I’ll stop writing. So they let him go and and I published him at Doubleday instead.

KA: So your writers like you.

NT: They’re incredibly loyal.

KA: Why did you leave Houghton Mifflin?

NT: Houghton Mifflin was a wonderful house, and the house I really belonged at. I was traveling back and forth on the shuttle from Boston, where their main office was. One summer I traveled 900 miles every week and I had gotten nothing done that was worth doing.

KA: So leaving them was a transportation issue.

NT: Yes, I really resigned from the Eastern Shuttle not from Houghton Mifflin.

KA: What does the logo of your imprint stand for?

NT: It’s a tree and the reason is because that’s where I want to be: outside reading under a tree.

KA: And here we are!

NT: Yes, here we are.

KA: How do you choose which books to publish?

NT: It’s really what I like. It’s very personal and also I do think I have a responsibility to the company. I do look at how will we promote it, for instance. But really, there are three things for me: one is that the author is a storyteller; two that she or he uses the language very well and three, that she or he is passionate about the subject; that transfers to the reader.

KA: Once you find a book that fits your criteria, how do you like to work with your authors?

NT: Each one is different. If there’s something I don’t understand, I ask them about it. That’s mostly what I do.

KA: So you are not in the weeds with them.

NT: No. They are all good writers. I ask them questions. One of Ian McEwan’s books needed a great bit of work and I remember sending him six pages of queries and giving them also to our President, Sonny Mehta, who had been Ian’s editor in England before he came to the United States. Anyway, after Ian revised it, Sonny said to me, I see he took your advice. But I don’t look back and forth. I just read revisions like I would read a new manuscript. With someone like Pat Conroy I did a lot of cutting, whereas Thomas Cahill, he knows so much and wears his knowledge so lightly that I end up saying, please say more about this or this. Ian McEwan rarely needs an editor.

KA: Do you use the same criteria for fiction and nonfiction?

NT: The same. With nonfiction I may get a proposal and a partial, unless it’s a first-time writer and then you want the whole manuscript not just a partial.

KA: How have you seen the role of an editor change since 1966 when you edited Papa Hemingway?

NT: Particularly in the last two years, it’s become much more commercial and there are more small publishers. Also, there is Amazon Publishing, so there’s no longer—what do you call it—a gateway to books anymore.

KA: Is that good or bad?

NT: I don’t know. It used to be that agents knew the kinds of books editors liked. Now authors can get books published anywhere.

KA: That’s why we named this series “Interview with a Gatekeeper.” We are curious as to who is minding the gateway to books.

NT: [Laughs] I mean, someone like Amazon, they have their own selling machine, so they can do what they want. I think publishing is going through its adolescence, through some growing pains. Some people have given up, and happily Sonny Mehta hasn’t. There are so many independent publishers now, and some people are publishing on the Internet, then you have the reliable old publishers, which are getting perhaps too big. Doubleday and Knopf merged and then merged with Penguin, all of which is part of Random House. Also Crown and Putnam. And of course we’re owned by Bertelsmann, a German company. I think it may be just too much. It’s gotten so corporate. We all go on doing the same things we used to do but the finances are more corporate and you get so much information coming at you. It’s just too much. What’s happening to publishing is it’s very unprofitable now because people are going so fast and have lost touch with the authors unless they write bestsellers. People have to be able to sit still and concentrate to read a book. The generation that started reading the Harry Potter books will change that.

KA: So McEwan, Conroy, and Atwood have been able to make decent livings as writers. That’s something that seems to have changed since you started working as an editor. Writing used to be much more lucrative.

NT: Until American authors make enough money on their foreign rights, they shouldn’t quit. And I’ve told authors that. Those three, McEwan, Conroy, and Atwood all are published in other countries as are a lot of my authors.

KA: So you are saying keep at it and eventually you will earn a livable wage?

NT: Before people recognized Ian McEwan, I had published seven of his books. Before Atwood really was successful she had published 14 books in this country. So yes. Atwood is absolutely marvelous. She’s so brilliant. She really is.

KA: Have you published her poetry?

NT: When I went to Doubleday, she had a book of poems—and it’s interesting because her poems usually give me an idea of what her next novel’s going to be like—and I said very honestly to her, I think you should keep your poetry with Houghton Mifflin. Doubleday will do just as well at the outset but they won’t keep it stocked the way Houghton Mifflin will.

KA: So there are fiscal decisions, too, about what books you publish.

NT: You want to do what’s best for the author.

KA: What else do you do that’s best for your authors?

NT: A friend of ours said, When you talk about your books you sound so excited by them that you immediately want to read them. When I was reading Tolkien’s No Man’s Land I was called to dinner and I was right at the beginning of the battle of the Somme so I wouldn’t come to dinner! Finally, at 11 o’clock that night I ate dinner and when I went to bed I couldn’t sleep because the book kept going through my mind.

KA: Just like the men going over the redoubts in the Somme in their endless stampede.

NT: My father fought in WWI with the British. He used to say meeting my mother’s family was worse than going over the top. I never knew what that meant until much later.

KA: What was your family like?

NT: I think he said that just because there were so many! Mummy was from Houston, Texas.

KA: You grew up in New York, however, right?

NT: Yes, but the way they met was when Daddy was in Houston with Jesse Holman Jones, the politician—this was during the FDR administration—and he was at a party at the home of Dassie Boone. All the politicians were there. Mummy was doing something that night with Bonnie Boone, a cousin, and they had returned to Bonnie’s house to change clothes, as they were going off to another party. My mother had a beautiful voice and had studied opera, so Dassie asked Mummy if she would sing to the guests while Bonnie was upstairs changing. Mummy did and my father was just enchanted by her! He found out where she sang, in what church, and then when he went back to New York, he began writing to her. I think they saw each other a few times in Texas but then Daddy wrote eight letters to her and they were married. Mummy left her beaus in Chicago, where she had been studying with this very famous voice teacher, and Daddy took a train down to Texas and that’s when he met the whole family.

KA: So that’s how you ended up in New York.

NT: Yes, he brought Mummy to New York and they lived on East 57th Street. I think soon after I was born, they moved to Rye, where I grew up.

KA: Did you have siblings?

NT: I had an older sister and an older brother, both of whom are dead, and a sister 15 years younger than I am.

KA: Your mother had a big family you said?

NT: Yes, but we never knew our Texas cousins. Travel wasn’t that easy. You just didn’t just get on a plane the way you do now.

KA: What did your father do for a living?

NT: My father was with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation under Roosevelt so he was a banker. When so many firms did not survive the War, Daddy would go into these companies that had bellied up and help them get back on their feet. Mummy called it charity work. He graduated from Columbia and then Columbia law school. I asked Mummy one time, why did Daddy leave the law? Because clearly he didn’t like banking very much. And she said he thought the law was too suspect. I mean my interest in such books as Behaving Badly has a lot to do with the fact that my parents were incredibly ethical. And they both read a lot. Mummy always had two books she was reading and as children, we were sent down to the village to the lending library to get the newest one that had been published.

KA: What’s the first book you remember having an affect on you, as a young woman?

NT: I don’t think I read much then. We lived in a very social town.

KA: You were a debutante in 1951, right?

NT: Yes. [Laughs]. I remember at one point my father became quite alcoholic and Mummy would simply say to me, When your date comes to pick you up at night, make sure you’re ready, which was a signal that Daddy had had too many martinis. I mean, that was just it. We talked in euphemisms. Daddy was a great fan of Philip Roth but he’d say, Why does he have to use that language? Suicide is also one of my favorite book subjects. When we were young, our movie house in Rye was only open on Fridays and Saturdays so we’d go to the movies in Stamford sometimes. On the way, we’d drive over this road and someone in the car would always say, That’s where Henry Fonda’s wife committed suicide. I was brought up a Catholic, and you know the Catholic’s position on suicide. Well, it never made make any sense to me because the one thing you are entitled to is your own life.

Have you ever read the book The Savage God by Al Alvarez? It was a book about suicide I published. It was about his own attempt and the culture and theory surrounding suicide. When the manuscript came to me I was so excited. When I talked to the Editor-in-Chief and the head of sales, they both asked, Is it for or against or a how-to book? They were just uncomfortable with the subject. The other author I really love is Graham Greene. He’s probably, from my early years, one of my favorites. He tried to commit suicide once, too. So that’s why when asked if it was okay to publish the fact that Hemingway committed suicide, I had no problem with it. I suppose quite a number of my books are about suicide.

KA: What do you think publishing a book about suicide can do?

NT: It took the subject out of the shadows.

KA: Which is against the teachings of the Catholic church.

NT: I went to the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Greenwich where I studied philosophy. I thought the Catholic Church was wonderful. Gay and I were married in 1959 in Rome outside the church, however.

KA: You went all the way to Rome then got married outside the church?

NT: [Laughs] Well, Gay never wanted to be married. He thought writers shouldn’t be married. Before we left for Rome on vacation, I told my parents he and I were getting married in Rome. I went to the convent at the Trinità dei Monti at the top of the Spanish Steps and I told the nuns I would like to be married in the chapel there. They said, we haven’t had a wedding here, my child, in 50 years. So we got married in the Campidoglio, the city hall in Rome, and it was a very elegant wedding. Irwin Shaw was Gay’s best man.

KA: Wait, Irwin Shaw was Gay’s best man?

NT: Shaw was in town and he and Gay knew each other. After the wedding Shaw gave us a party at the Excelsior, where he was staying. Since they were making La Dolce Vita then, the Excelsior was filled with actors. We were this young couple that just got married and they thought, wasn’t that cute. My maid of honor was a young woman about my age who was having an affair with Pilade Levi, the head of Paramount Pictures in Rome.

KA: What do you attribute your long success as an editor to?

NT: Gay. And the fact that I love what I do.

KA: Gay?

NT: I mean, I had a job and I did it well, I’ll admit to that. But I always said to him, I will quit if you want me to, but he was very encouraging and very proud of my work.

KA: Gay said you didn’t read The Voyeur’s Motel before it was published, but do you generally read his manuscripts as he’s working on them?

NT: I don’t know why he didn’t want me to read the last one. I mean, he talked about it so I knew about it. He used to like me to read aloud to him so he could hear if there were any awkward moments or where I stumbled over the language.

KA: Your daughter Catherine once said you were “Velvet Hammer.” What did she mean by that?

NT: She was quoting Michael Korda, the Editor-in-Chief at Simon & Schuster. But I think it’s because I’m very passionate about what I do. For instance, I had always admired Thomas Keneally’s writing. One day, Tom sent me a letter from California saying there are these extraordinary papers there that pertain to the people who were saved from Auschwitz. I said, Can you tell me more? Can you write me a proposal? Simon & Schuster was not very keen on the idea. I don’t know how I finally wore them down but I guess I did. The thing was, I just thought the book was really important. That book was Schindler’s List. With that book I just didn’t give up; I wanted to publish it. If I really think something is good, I really want to do it and I want to be a champion for it.

KA: Why did you leave Ocean City, New Jersey, for rural Connecticut?

NT: The lawn.

KA: The lawn?

NA: I felt I bought a lawn here and it happened to have a house on it. I just missed having one, even though I had done the best I could in New Jersey where I had planted a garden and we had a wonderful old Victorian house. Also Ocean City was 130 odd miles from New York, where I was working, and much of that drive was on the New Jersey Turnpike. It was just awful. I had been in Connecticut visiting friends and various other people and I just loved the land. And it’s only 82 miles door-to-door from here to my office.

KA: What is the greatest joy of being an editor?

NT: I think the greatest joy is when the books do well for the author. And the fact that something I love is loved by other people. You want to share it with other people, the things that really make a difference.

KA: You also received the first Maxwell E. Perkins award from the Center for Fiction.

NT: Yes, and it’s the award that has meant the most to me, because when I read Scott Berg’s biography of Maxwell Perkins I thought, I could never be like that, like Perkins

KA: But here you are.

NT: It pleased me so! I just thought, Maxwell Perkins!

KA: What’s next for you?

NT: I’ll keep doing this but Pamela and Catherine, my daughters, keep saying, You could lecture on book publishing. But does anyone want to be lectured?

KA: Sure! One interesting thing, at least for me, is to see in what’s behind the book, what makes an editor interested in a book.

NT: Yes, it’s what attracts you. Do you know Owen Sheers? He’s an absolutely wonderful writer. After I read his manuscript for Resistance, an earlier book I ended up publishing, I said to him, This is really an anti-war book. And he said, Aren’t all books? I thought, we won’t make any money on it, but the book is just wonderful. So sometimes you do things that are just because they’re so good. His newest book, I Saw a Man, is terrific.

KA: What a great cover.

NT: I am very involved with the covers. This one took about eight tries until we finally got it. I also ask to see the inside design of the book, the lettering, and I always make sure the authors are happy with it.

KA: You’ve also published a lot of biographies.

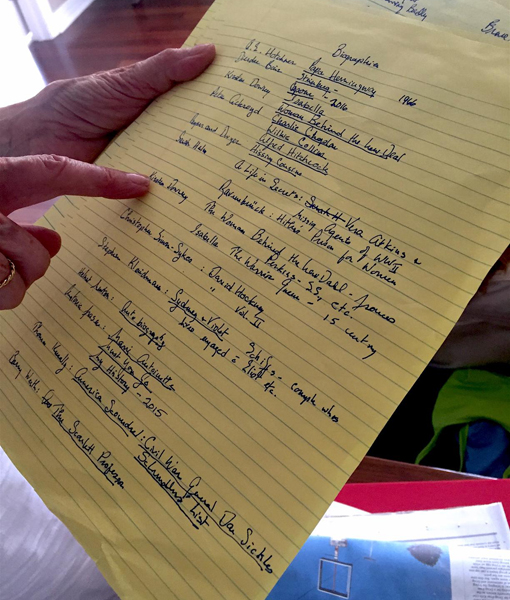

NT: It’s true but I hadn’t realized it. I began looking at biographies starting with Papa Hemingway [shows me a handwritten list of all the biographies she published] I mean these are fascinating people! I think there are about 60 biographies. I really hadn’t realized it.

KA: That might be another thing all books are about besides being anti-war: all books are about lives.

NT: Right!

KA: Who is going to publish your biography?

NT: No one. [Laughs]. Nobody wants to know about me.

KA: I think you are wrong.

NT: We’ll see.

In honor of her lifetime commitment to a high standard of literary prose and support of and service to biographers, writers of narrative nonfiction, and historians, Biographers International Organization is awarding Nan A. Talese the BIO Award for Editorial Excellence in October, 2016.