Home Archive by category Excerpts (Page 78)

Excerpts

The Night Swimmers

Peter Rock

"To swim with another person—out in the open water at night, across a distance, without stopping—is like taking a walk with-out the pressure, the weight of having to carry a conversation, to bring what is inside to the outside. Think of being with someone in a silent room, the tension in the air; water is thicker and you can’t talk, can’t stop moving. Instead, you’re together, struggling along, only glimpsing each other’s silhouetted arm or head for a moment, when you turn your face to breathe, a reassurance that you are not completely alone."

The Dragonfly Sea

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

"To cross the vast ocean to their south, water-chasing dragonflies with forebears in Northern India had hitched a ride on a sedate “in-between seasons” morning wind, one of the monsoon’s introits, the matlai. One day in 1992, four generations later, under dark-purplish-blue clouds, these fleeting beings settled on the mangrove-fringed southwest coast of a little girl’s island. The matlai conspired with a shimmering full moon to charge the island, its fishermen, prophets, traders, seamen, seawomen, healers, shipbuilders, dreamers, tailors, madmen, teachers, mothers, and fathers with a fretfulness that mirrored the slow-churning turquoise sea."

“The Return”

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

"The road was long. Whenever he took a step forward, little clouds of dust rose, whirled angrily behind him, and then slowly settled again. But a thin train of dust was left in the air, moving like smoke. He walked on, however, unmindful of the dust and ground under his feet. Yet with every step he seemed more and more conscious of the hardness and apparent animosity of the road. Not that he looked down; on the contrary, he looked straight ahead as if he would, any time now, see a familiar object that would hail him as a friend and tell him that he was near home. But the road stretched on."

Another Kind of Madness

Ed Pavlic

"The whole Inflation thing had been Ndiya’s idea. The old, half-empty lounge was there just down the street from Shame’s place. The piano was in the back already. It seemed obvious to her. But it wasn’t to him."

Famous Men Who Never Lived

K Chess

"It all ended in a rush nearly three years ago now, when the first lots of lucky people moved through the hole into this world. Groups of one hundred at a time—men, women, but no children—stepping dazed into the spaces between the grave markers of Calvary Cemetery in Queens. There were ten entry groups per lot, lots coming at precise hourly intervals, the hole closing up behind them each time like a wound healing in time lapse. Emergency crews had their hands full, moving the newest arrivals out of the way to make room for more. All of the newcomers told the same story—coordinated teams of domestic terrorists, young men radicalized by pro–America Unida messages hidden in visor games from the south."

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura

Christine Wunnicke, trans. Philip Boehm

"The fishmonger’s house lay in a shady mountain hollow high above the sea. It was a beautiful home, almost princely. Here the fish weren’t wares to be hawked but inventory that was managed in lucrative fashion, and the fishmonger, as it turned out, was a prince among fishmongers, although Shimamura and the student never learned how that had come about, or why fish and their management were so greatly valued there."

The River

Peter Heller

"They had been smelling smoke for two days. At first they thought it was another camp fire and that surprised them because they had not heard the engine of a plane and they had been traveling the string of long lakes for days and had not seen sign of another person or even the distant movement of another canoe. The only tracks in the mud of the portages were wolf and moose, otter, bear."

Unquiet

Linn Ullman, translated by Thilo Reinhard

"When Mamma and Pappa were an item in the sixties, Mamma’s face was so naked as to almost not be a face. It was constantly falling apart and putting itself back together again. Much has been said and written about Mamma’s face, her eyes, her lips, her hair, her unsettling vulnerability and the way in which all great actresses channel every emotion to the area in and around the mouth, but no one has said anything about her ears. When I was little, I liked lying close to her and stroking her hair, I didn’t yet have words for beauty, or for love; like most children I was more concerned with the size of things, whether they were big or small, and Mamma had big feet and big ears. We would lie in her double bed with its golden bedposts and pink flowery sheets, and she would let me stroke her hair while she read a book or spoke on the telephone. She often ended a phone conversation with the words Men–over and out."

A Season on Earth

Gerald Murnane

"Adrian didn’t tell his parents that he planned to give up study and spend the rest of his life as a public servant and poet. He spent the last of his money for textbooks on a book called The English Countryside in Colour, a railway map of the British Isles, a loose-leaf folder and a ream of foolscap paper."

“Wolf in the Basement”

Aurelie Sheehan

"When I was young, we kept a wolf in the basement. It was a compromise, where one of my parents wanted no wolf and the other wanted the wolf in the living room, and so together they came up with this solution. The wolf lived six steps down from the rest of us, and when we let him out it was from the very back door, the one that faced the forest."

Binstead’s Safari

Rachel Ingalls

"Stan sat directly behind a wiry man of about his own age: late thirties to early forties. The man was named Carpenter. He worked for the government, not for the tourist board. He had told everyone about safety measures, and disappointed the Frenchwoman who was traveling with them. She was a professional photographer and, like many photographers not working inside actual war zones, dressed in what looked like genuine combat-issue clothes. Stan had thought when he first saw her that she was a very small soldier. She was smoking Gauloises until Carpenter said something to her about a fire risk. Stan was pretty sure the rule had been made up just that minute."

Why Was Guantánamo Diary‘s Author Denied a Passport?

Mohamedou Ould Slahi Says He Needs Medical Care in Europe.

Leading Men

Christopher Castellani

"For thirty years, Anja has lived in his city. Now that he is gone, it turns to her an unfamiliar face. From the safety of the train, behind the thick-paned window, she recoils from its lopsided mouth, its filthy eyes. When she steps off the platform, it looks away in recrimination. Hatching a plan. Lying in wait. She would apologize or confess if she had cause, but she has no cause. What is the old saying? The heart takes no commands. She loved him, but she has never loved where he brought her."

Vacuum in the Dark

Jen Beagin

"It was hard, misshapen, probably handmade. Nut brown flecked with beige. Sandalwood soap, it looked like, sitting on a porcelain plate with a peacock painted on its edge. Having just finished scrubbing the toilet, Mona grabbed the soap to wash her hands. Once wet, it fell apart and caked her fingers like clay. The stench, although vaguely sweet, brought instant tears. She blinked the tears away and peered at her hands. The beige flecks, she saw now, were undigested seeds, and something long, wet, and army green had been swirled into the middle. The green thing, whatever it was, had been binding it all together."

The Body Myth

Rheea Mukherjee

"The woman was sitting on a park bench in West Point Gardens, where I came every Sunday for a five-kilometer walk. She couldn’t see me, but I had stopped midstride to stare at her. I looked at her for three reasons: (1) her face was twisted in contemplation; (2) she was wearing a beige kurta with a transparent golden dupatta; and (3) she was fucking gorgeous."

Birthday

César Aira, trans. Chris Andrews

"Recently I turned fifty, and in the lead-up to the big day I began to have great expectations, but not really because I was hoping to take stock of my life up to that point; I saw it more as a chance for renewal, a fresh start, a change of habits. In fact, I didn’t even consider taking stock, or weighing up the half-century gone by. My gaze was fixed on the future."

“Alice”

Maryse Meijer

"Friday nights used to be Steak Nights. Exactly ten ounces of prime rib for me, eight for Wendy, six for our daughter Alice. Other nights we had fish and green vegetables, tofu and brown rice; but Friday was about flesh and blood."

American Pop

Snowden Wright

"Word spread fast. During those first couple of months following its invention, the house soda of Forster Rex-for-All remained a local treat, known only to the genteel citizens of Batesville proper. Soon enough the county farmers and field hands discovered the drink. In the evenings they would cool down with a glass on their way to deliver a wagonload of hog shorts. In the mornings they would perk up with a glass while eating a drop biscuit made for them by the missus."

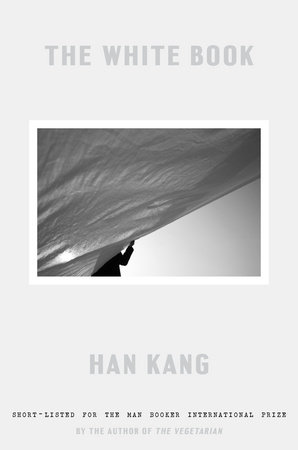

The White Book

Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

"With each item I wrote down, a ripple of agitation ran through me. I felt that yes, I needed to write this book and that the process of writing it would be transformative, would itself transform into something like white ointment applied to a swelling, like gauze laid over a wound. Something I needed."

Page 78 of 101