Poop

It was hard, misshapen, probably handmade. Nut brown flecked with beige. Sandalwood soap, it looked like, sitting on a porcelain plate with a peacock painted on its edge. Having just finished scrubbing the toilet, Mona grabbed the soap to wash her hands. Once wet, it fell apart and caked her fingers like clay. The stench, although vaguely sweet, brought instant tears. She blinked the tears away and peered at her hands. The beige flecks, she saw now, were undigested seeds, and something long, wet, and army green had been swirled into the middle. The green thing, whatever it was, had been binding it all together.

“Spinach,” Mona gasped. “What the fuck.”

“What’s happening?” she heard Terry whisper.

Mona leaned against the towel rack, reeling as if she’d been punched in the face. “Someone shit in the soap dish,” she said after a while. Terry didn’t say anything. Mona’s upper lip was sweating. She made the water as hot as she could bear and rinsed her hands.

“I mistook it for fancy hippie soap, Terry,” Mona said, and swallowed. “Like some dumbass.”

“Don’t panic,” Terry said in her most gentle voice.

“My mouth feels weird,” Mona mumbled.

“You needn’t worry,” Terry said swiftly. “You’re a non-puker, right? Keep breathing through your mouth. Keep rinsing. Look for some real soap under the sink.”

“Yeah, no, okay,” Mona said.

In the recent past, Mona would’ve turned to Bob, her nickname for God, but Bob was often a flake in emergency situations. Terry would get her through this. Most days, Terry was simply a sober and inquisitive voice in her head, interviewing her about the day-to-day hassles of being a cleaning lady in Taos, but occasionally she switched roles and became something more: coach, therapist, surrogate parent. At twenty-six, Mona was a little old for imaginary friends, but Terry wasn’t just anyone. She wasn’t some stranger off the street. She was a real person who lived in Philadelphia. In fact, for well over a decade, on an almost daily basis, Mona had been listening to Terry on NPR.

“From WHYY in Philadelphia, this is Fresh Air,” Terry said, apropos of nothing. The jazzy theme song accompanied Mona’s search for soap under the sink. Nothing liquid available, but there, in the back, a water-stained box of Yardley’s English Lavender. She tore open the box and washed her hands vigorously, surgeon style.

“The air? Not so fresh today, Terr,” Mona said.

“Is it human?” Terry asked.

Mona frowned at herself in the mirror. “I believe so.”

“Could it be the dog’s?” Terry asked.

The clients owned an overweight dachshund named Dinner. Dinner was a dream. This wasn’t Dinner’s work.

“This was human,” Mona said, “and . . . hard-won, if you know what I mean.”

“I don’t,” Terry said.

“Severe constipation,” Mona said. “That’s what this person suffers from.”

“Among other things, obviously,” Terry said gamely.

Why hadn’t she smelled it right away? Well, because it was old, that’s why. Three days old, perhaps four.

“What are you going to do?” Terry asked, sounding worried.

Mona didn’t answer. There was still a little shit in the soap dish. Now that his beautiful feathers were soiled, the painted peacock did not look so serene. He looked startled and insecure. Part of her wanted to smear the remaining shit on the mirror. She could draw a heart with it, and then add some wings, and top it with a halo. Feces graffiti. Then she would leave the house and never look back.

Instead, she upended the dish over the toilet and flushed, and then swabbed everything with diluted bleach.

“You just flushed the evidence,” Terry said, and sighed. “Nice work.”

“This isn’t TV, Terry,” Mona said patiently. “I can’t send it to the lab for testing. I can’t dust it for fingerprints.”

“Who do you think did this?” Terry asked, bewildered.

“Who knows,” Mona said.

Actually, Mona had a couple of theories, but she wasn’t ready to share them just yet.

“Someone from the party?” Terry offered.

One of the owners was a therapist and had conducted a group therapy session in the living room the previous evening. Mona hadn’t been there, of course, but they’d left pamphlets and pretzels everywhere, and a big white board with a bunch of crap written on it, like “Location/Occasion” and “Pleasant Childhood Memories” and “Open-Ended Questions.”

“Maybe you should write your own note on the whiteboard,” Terry suggested. “Such as, ‘Whoever shit in the soap dish owes me two hundred fifty dollars.’”

Mona examined the porcelain sink. There was an exciting new rust stain near the drain. From her cleaning bucket she removed a bag of cut lemons and a jar of sea salt. She sprinkled a generous amount of salt onto half a lemon, which she then rubbed over the rust. The stain disappeared in seconds.

“Maybe you don’t give a shit,” Terry said, and chuckled at her own joke.

Mona shrugged. She didn’t want to discuss it any further, as she already knew that she wouldn’t bring it up with the owners. No one was home, anyway, and she was almost finished here—she’d saved the guest bath for last. Besides, what was she going to do—wait around? Leave a voicemail?

“I just annihilated a rust stain,” Mona said. “Again. I’m telling you, lemon juice and salt are the shit—”

“I don’t get why you’re not more freaked out,” Terry interrupted. “About the . . . actual shit.”

“I’m going through a breakup, Terry,” Mona said.

Terry was quiet for a few minutes. Mona polished the faucet with Windex and a dry rag.

“I didn’t know you were in a relationship,” Terry said finally.

“It was short-lived,” Mona said. “And disturbing.”

“Big surprise,” Terry said.

“Anyway, if I say something, they win,” Mona said. “So, I’m letting this one go. But it’s good to know you’re not squeamish about this sort of thing, Terry. You handled that like a trouper. I don’t know about you, but I feel like we’re even closer now.”

Terry made no comment, which was fine. It was after five o’clock and she probably had better things to do. Despite the late hour, Mona went to town on the outside of the toilet, polishing all of its parts with 409, including the often-overlooked bolt covers.

*

The following week, three shits, same house. The first one was in the kitchen, a small brown frown sitting on a stool.

“A stool on a stool,” Mona said out loud. “Wow.”

Upon closer inspection, not a frown—a smile. The thing had teeth, or at any rate, here and there something hard and white. She took a photograph of it, and then held her breath as she picked it up with a paper towel. It was a long walk to the toilet.

The second was on a low shelf in the living room. This one resembled a dense, muscular finger with a swollen knuckle. The finger was pointing at a braille edition of e Old Man and the Sea. Again, she photographed it, and then tried to think of the significance, if any, as she carried it out of the living room, but she could barely remember the story. An old man. A young boy? The sea. A big fish. He almost dies. The End.

The third was hiding behind a potted palm in one of the guest rooms. This one was sweating. It seemed a little shy. It was as if it had been onstage and had suffered an attack, and was now recovering in the wings. Up close, however, she saw that it was quite full of itself. It also seemed to have acne. She couldn’t bear to carry it anywhere, so she tossed it out the window. Fuck it.

“Let me ask you something,” Terry said suddenly. “Have you ever encountered this sort of thing as a cleaning lady?”

Terry was using her on-the-air voice, which happened about once a week. Mona gathered her thoughts as she shut the window and threw away the dirty paper towel. The only thing left to do now was vacuum.

“Well, Terr, I did find a small log in a bathtub once,” Mona said, and plugged in the vacuum. “But that guy—the client—was on chemo. This was two years ago, when I first moved to Taos.”

“But this is different, wouldn’t you agree?” Terry said. “This is deliberate. What’s the message here?”

The vacuum whined and then made a screeching noise. Something metal was trapped in the brush roller. She cut the power, flipped it, removed the bottom plate. A nickel and a paper clip fell out.

“This whole situation may be karmic, Terry,” Mona said, pocketing the nickel and paper clip. She reassembled the vacuum. “Growing up in Los Angeles, my best friend in grade school was this girl named Penny. She was an extrovert, a great kisser, and, as I recall, a pretty good gymnast. At recess, she would drag me to the restroom to watch her take a dump right next to the toilet. I either gagged and almost puked, or laughed so hard I pissed myself. Afterward, we hid outside and waited. Penny did this sort of thing wherever we went. She pooped on doorsteps, in driveways and gazebos. At parties, she pooped in closets. She pooped in dressing rooms at the mall. I liked to think of it as performance art, and myself as an artist’s assistant, but then Penny pooped at summer camp, in the middle of the stream where everyone bathed and drank water, and I realized that Penny was not an artist. She was a terrorist.”

“And you were an accomplice,” Terry said after a pause.

“I suppose that’s right,” Mona said.

“Do you know what became of her?”

“Yes,” Mona said. “She became Scarlett Johansson.” Terry chuckled softly.

“No, but I wonder about her,” Mona said. “I bet she’s a Hollywood producer or a lawyer or a plastic surgeon or something.”

“Don’t be offended,” Terry said, “but any way this is all in your head?”

“The shits are real, Terry,” Mona said. “They have heft. They engage all the senses.”

“Start keeping a record of some kind,” Terry suggested, as Mona finished vacuuming. “Indicate the time of day, the location, plus a brief description, and maybe include a drawing.”

Not a bad idea. It could be a kind of art project. In a notebook, she might write something like: Possible suspect: Chloe, daughter, age seventeen, artist. Room: neat as a pin. Keeps diary, decent writer. Favorite movie: Donnie Darko.

*

Mona headed home. She lived in one half of a hundred- =year-old adobe ranch house on the edge of a valley. An older married couple rented the other half. Nigel was a British man in his forties; his wife, Shiori, was Japanese and half his age. They made music with homemade instruments and dressed in matching pajamas. They’d moved to Taos from Indonesia where they’d spent twelve years meditating and gazing into each other’s eyes, and had maintained a willful and near-total ignorance of popular culture. They had no idea who Philip Seymour Hoffman was and didn’t care, and had never read a book published after 1950.

In some ways, they reminded her of John and Yoko, but, as they were both terrible musicians, she called them Yoko and Yoko. They occupied the front of the house, which was all sunshine and flowers, and had a large yard, a paved driveway, and south-facing windows, while Mona lived in the back, in perpetual shade and darkness, and had to sleep with a hair dryer in the winter.

When she pulled into the driveway, they were standing on her porch in their traveling pajamas. They were often waiting for her when she came home, but Nigel was peering into her kitchen window, which was unusual. She cut the engine, opened the truck door, and asked if everything was okay.

“We’re on our way to a meditation retreat,” Shiori said, “but we thought we heard a dog barking in your living room.”

Six months later and they were still bringing up George. “My dog is dead,” Mona said.

“It didn’t sound like your dog,” Nigel said patiently.

“Big,” Shiori said. “It sounded big. Like a wolf.”

Mona pulled out her house key. Yoko and Yoko put their arms around each other’s shoulders and stepped toward her door.

“Guys, I’ve had a weird day,” Mona said. “Not sure I’m in the mood tonight.” She watched them look sideways at each other. “No offense,” she added, uselessly. They were never offended by anything she said. She both loved and despised this about them. “But let me get your take on something. I keep finding little shits in this house I’m cleaning. Human shits left around on purpose. It’s obviously one of the inhabitants of the house, but what would compel someone to do that? In their own house?”

“Rage,” Shiori said, after a pause.

“It’s . . . aggressive,” Nigel agreed slowly. “I would say this person feels trapped or caged and is very angry about it.”

“But one of the shits was on a stool,” Mona said. “A stool on a stool— get it? at seems sophisticated and somewhat playful, no? Maybe this person just has a fetish for pooping in weird places.”

“Well, then it must be someone who doesn’t live in the house,” Nigel said. “Your own house is not a weird place, is it?” Yoko and Yoko smiled smugly.

“Anyway, that’s my two cents, as it were,” Nigel said nasally.

“I’m going to take your two cents and rub them together,” Mona said, “while I watch TV.”

They took a step back. Television was kryptonite for Yoko and Yoko. They refused to enter her side of the house unless she covered the entire set with a heavy blanket.

“Would you like us to wait here while you check for the dog?” Shiori asked.

“I don’t hear any barking,” Mona said. “So, I don’t think Cujo’s inside.”

“Cujo?” Nigel asked.

“Stephen King,” Mona sighed. “Never mind.”

*

Almost three weeks later, Mona was sweeping the kitchen floor of the shit house. The shits had vanished. Christmas was around the corner. Dinner was a little fatter; Mona was bloated and about to bleed. Her primary happiness that day was her new broom. Among her favorite sounds in the world: stiff cornstalk bristles on a hard surface. She was in the middle of telling Terry how important it was not to sweep like a gringo. “White people are terrible sweepers,” she was saying. “They don’t know how to caress the floor with the bristles, how to coax the crumbs from under the—”

“But aren’t you a white person?” Terry interrupted.

“Yeah, but I don’t sweep like—wait, is that a rum ball?” There’d been rum balls in the fridge the previous week. Buttery, chocolatey, not too sweet. She’d checked the fridge first thing that morning, hoping for more, but they were gone. Someone must have dropped this one. The Last Rum Ball.

“Should I eat it off the floor?” she asked Terry.

“Why not,” Terry said. “You ate all that candy corn off the carpet at the Shaws’ last month.”

Mona picked it up—slightly deflated, but otherwise perfectly intact—and squished it lightly between her fingers.

“That’s not a rum ball,” she heard Terry say.

Mona dropped it as if it had bitten her.

“I think you might need glasses,” Terry suggested.

“Fuck,” Mona said out loud.

She scanned the floor—no other turds. Just this little one at her feet and now some shit on her fingers, which she absentmindedly wiped on her favorite apron.

“‘Turd’ is perhaps the wrong word,” Terry said calmly. “Turds are curved.”

“What would you call this?” Mona asked.

“Poop,” Terry said. The poop was upsetting, no question. More upsetting, perhaps, than the previous poops, because, like an all-purpose idiot, she’d mistaken it for something sweet and delicious. Perhaps she should leave it on the floor for some other fool to deal with. She asked herself what a healthy, well-adjusted person would do.

“They would call the owners and complain,” Terry answered.

“Hmm,” Mona said.

“Where’s the dog?” Terry asked. “You might bring him in for questioning.”

“Dinner!” Mona shouted. “Come!”

Dinner padded into the kitchen from his nap in the living room. His ears were inside out. She rubbed his head, righted his ears, and then pointed at the poop.

“Din-Din, is this yours?” she asked. “Did you do this?”

He approached it, took a tentative sniff, and sneezed. He made steady eye contact with her and then abruptly left the kitchen.

“Wasn’t him,” Mona told Terry.

Mona scrubbed her hands at the sink. The bogus rum ball she covered with a paper towel and tossed into the trash. Someone had wanted it to resemble a rum ball and strategically placed it under the cabinets. Was this same someone watching her right now? But where was the hidden camera? In the cabinets, or maybe embedded in the ceiling. She imagined the view from above. There she stood, in her shitty apron, gazing at the trash, lost in her stupid thoughts. Then she pictured herself as a grainy, black-and-white figure on a tiny screen. But who was watching this screen?

“We can rule out the lady of the house,” Mona said finally.

“Why’s that?” Terry asked.

“She’s blind,” Mona said.

*

Mona had met the homeowner six months ago when things weren’t going so good. Her only friend, Jesus, had moved hours away and three of her best clients had sold their houses. In her grief, she’d contracted an existential flu. This one had been hard to shake. The blood vessels in her eyes kept bursting, an unbearable scalpy smell lingered in her nostrils, and her insides felt dirty and ravaged. For the first time in her career, she’d canceled her clients for the week, and for three days she didn’t see or speak to anyone, not even Yoko and Yoko or Terry Gross.

On the morning of the fourth day, she remembered drinking Pepto Biz from the bottle while reading the quote taped to the refrigerator: “The cure for anything is salt water: sweat, tears, or the sea.” Isak Dinesen, author of Out of Africa, which she’d never read. The movie, however, was among her favorite period dramas to blubber over. But, as was her custom, only during her period. Still, she decided to take the woman’s advice. The sea was off the table, obviously, so she would try tears and sweat, possibly simultaneously.

The tears did not come easily. She gnawed on her hand and produced a few drops of salt water, but, strangely, only out of one eye. The self-pity she felt at having to chew her own flesh made the other eye water. She stuck her head in the closet and cried. It had always been easier to cry in confined spaces. Closets, shower stalls, certain compact cars. She wept silently with her head in the shirt section of her hanging clothes. You’re okay, cookie, you’re okay, she told herself. There, there, cookie, let it out.

She’d never called herself cookie before.

Later, seeking salt water from sweat, she’d forced herself to run laps at the high school track. The place was deserted and dimly lit. She ran holding her tits to her chest, as the only bra she owned was an ancient padded thing with loose straps. Someday, and soon, hopefully, she could buy a real sports bra. Cupping her chest was a little like running in handcuffs, but obviously preferable to her tits flopping around.

She wasn’t running so much as trudging. Her so-called running shorts were high-waisted, brocade, the wrong shade of pink. Thigh-chafers. She wore her hair in two long braids, one thicker than the other, which tilted her equilibrium. Still, she managed five laps in the middle lane. When her back began to bother her during lap three, she took to skipping. Forward, backward, sideways. It slowed her down but was somehow more satisfying than jogging. In her fantasy, skipping became an Olympic sport for which she’d won the bronze. Twice.

“No gold?” Terry asked.

“If I had a sports bra,” Mona said. “Maybe.”

She repeated the salt water cure the following day. When she arrived at the track, a woman around Mona’s age was running in the outside lane. Then Mona noticed a long white stick tipped with bright red. The woman ran with it held out in front of her. Mona squinted at her face. Those weren’t sunglasses, she saw now. The woman’s eyes were covered with a kind of blindfold.

“Have you ever seen a blind person run?” she asked Terry cautiously. Terry didn’t answer.

“I’ll take your silence as a no,” Mona said. “But let me tell you, Terry, it is really something. Honestly.”

From the bleachers, Mona quietly watched the woman. She was a better runner than Mona, and in better shape overall. She didn’t falter once, and her stick barely touched the ground. The fingers of her free hand fluttered as she ran, which Mona found endearing. Her gait was steady and confident, as if she were being pulled along by a large, invisible dog. A dog she adored and trusted completely.

“Or God?” Terry offered.

“God, dog, palindrome,” Mona said.

Mona coughed loudly as the woman passed for the third time, but the woman didn’t flinch. She was also about three and a half times prettier than Mona.

“Five and a half,” Terry corrected her.

Mona was handsome and vaguely ethnic looking. The blind woman was not ethnic looking. Nordic, perhaps, and highly desirable to a certain kind of man. The tall, rugged, Mr. Man type. The Mr. Man type was rarely attracted to the likes of Mona, which was a shame because she was often attracted to Mr. Men.

She began a slow slog in the opposite direction. Her legs felt sluggish and unresponsive, as if she were running in a dream. She and the blind woman were alone on the track. Each time they passed each other, the woman turned toward her slightly and smiled, as if sensing Mona’s unease. Her smile was a tad rapturous. It seemed to say, “I am not actually blind. I can see you perfectly. I know you’re holding your tits, for example, and I think you’re wonderful.”

Mona smiled back nervously. She felt this way around some toddlers and dogs: convinced they knew her darkest, most corrupt thoughts. Like the urge to trip the woman and watch her fall on her face. To distract herself, she started skipping.

“There are certain types of people you encounter over and over in life,” Mona mused to Terry.

“Recurring types. For some people, it’s drunks. For others, it’s drummers. Or doctors. You know? Or redheads, chefs, amputees. People with herpes—”

“I get it,” Terry said impatiently.

“For me, it’s the blind,” Mona said.

This was a lie. She wasn’t sure why she was lying to Terry, of all people but the concept was intriguing. She closed her eyes and continued skipping. She counted to five and was terrified, but she kept going. Then she felt something strange lapping at her ankles. A warm, knowing tongue. The tongue was doing something incredible to the backs of her knees. Now it rested in the crack of her ass. She felt suddenly and acutely blessed.

“The tongue of God,” Mona announced to Terry, “is currently parked in my buttcrack.”

“It’s euphoria,” Terry explained. “Triggered by endorphins.”

Mona opened her eyes, but only long enough to negotiate the corner. She continued skipping, eyes closed. She felt the woman pass her again. The tongue of God transferred itself to her brain and began licking her cerebral cortex. She laughed for several seconds. Then she found herself crying, which was just as pleasant.

“The cure for anything, it appears, is skipping blind,” she told Terry.

“Doesn’t sound as, uh, insightful as Isak Dinesen’s quote,” Terry said, and giggled.

It was always good to hear Terry laugh. Mona laughed, too. Then she tripped and fell hard on her right forearm and knee. Her knee was crunchy to begin with and began throbbing. Mona quickly hobbled o the track to the grassy middle. The woman slowed to a stop, ear cocked, listening for something. Coyotes? Mona listened, too. She realized the woman was listening for her. Mona.

“Hello,” Mona called out. “Are you looking for me?”

The woman waved and began walking in Mona’s direction, tapping her stick.

“I’m on the grass,” Mona said uselessly, rubbing her knee.

Now the woman was standing too close with her face pointing the wrong way, as if examining Mona with her left ear. Her earlobe was covered in tiny hairs. Mona checked the woman’s legs—same deal, only longer.

“I believe the term is ‘peach fuzz,’” Terry said jovially.

It was not unattractive. In fact, it was titillating, the thigh hair in particular. It also made sense. If you’re blind, are you really going to bother shaving?

“I heard you stumble,” the woman said, turning to face Mona. “You okay?”

“Oh yeah, I’m fine,” Mona said. “Thank you! You didn’t have to stop—”

“I’m blind,” the woman said quietly, and looked toward the ground. “Not deaf.”

“I’m shouting!” Mona shouted.

The woman gave her an amused frown. Mona frowned back, and then kept frowning. It felt good not to have to fix her face. The woman wore the sort of blindfold one used for sleeping. An eye mask. Mona envied it for a few seconds. She wanted her own eye mask.

“It’s funny,” Mona said, clearing her throat. “You kept turning your head toward me when we passed each other, and for a second I thought you were checking me out.”

“I was,” the woman said. “I was smelling you.”

Since the woman couldn’t see her, Mona went ahead and sniffed her armpit. Smelled like deodorant.

“How’d you know I wasn’t some creepy dude?” Mona asked.

“Dudes don’t skip,” the woman said. “At least, not around here. And you don’t smell like a dude.”

“What do I smell like?” Mona asked.

The woman seemed to mull it over while holding her stick against her chest.

“Suicide,” she said at last.

Mona gulped. She’d reached a personal high of 7.8 on the Sui-Scale that very morning. The Sui-Scale was a number reflecting her desire to end her life. Like the Richter, a difference of one represented a thirtyfold difference in magnitude. She’d spent over an hour researching suicide methods on LostAllHope.com. She settled on the gas-and-bag method, which had struck her as most affordable and least messy, and which the site warned was not for gestures. Helium was the preferred gas. Mona had imagined breathing in the helium and then talking to Terry in a squeaky helium voice, the bag over her head. They called it an “exit bag,” which she’d very much liked the sound of.

“What does suicide smell like?” Mona asked nervously.

For a second she expected the woman to say helium, even though helium was odorless, as were suicidal thoughts about helium. And thoughts in general.

“Strawberries,” the woman said, deadpan, as if it were obvious.

Mona heard herself laugh, startled. The woman was fucking with her. As she hadn’t been fucked with in forever, she’d forgotten what it felt like. It was . . . arousing.

“I’m kidding,” the woman said at last. She stared absently at Mona’s tits. “You smell clean,” the woman said. “Not like bar soap, but like . . . something else.”

“I’m probably sweating Windex,” Mona said. “I’m a cleaning lady.”

The woman left her mouth open when she smiled. She had the unrestrained, slightly goofy expressions of someone who’d never studied herself in a mirror.

“When I was in high school,” the woman said, “my mother shot herself in the kitchen. We got a cleaning lady after that and the whole house reeked of Pine-Sol for years.”

Mona glanced at her watch. Five minutes hadn’t passed, yet the woman was revealing her most intimate secrets. Often, after Mona copped to cleaning toilets for a living, people took it as a cue to be candid. People probably did that with prostitutes, too. But this might have been a blind thing. Wasn’t it easier to be intimate in the dark?

Or maybe this wasn’t so intimate. Maybe the woman was simply from California.

“Are you from California?” Mona asked.

“Colorado,” the woman said.

Close enough. In any case, there would be no need to censor herself.

This was clearly someone to whom you could say pretty much anything, a quality Mona valued highly, after having spent a decade in New England.

“Sorry about your mother,” Mona said. “ at sounds super shitty.”

“You should immerse yourself in nature,” the woman advised. “You know? To counteract the cleaning chemicals.”

Mona nodded vaguely, even though the woman couldn’t see her. It occurred to her that there was probably a lot of talking involved with the blind. “Well, I used to take long walks in the woods. I even collected leaves at one point, but I kept . . . leaving them places.”

“What about you? Are you from California?”

“Los Angeles, originally, but I was shipped to Massachusetts when I was thirteen.”

“Yikes,” the woman said. “Why?”

“Bad behavior,” Mona said.

“What brought you here, to the high desert?” the woman asked. “Love, sort of,” Mona said. “I called him Mr. Disgusting. We met at a needle exchange in Massachusetts. He was clean when we met, but of course he relapsed six months later. In his suicide note, he suggested I move to Taos. He said he’d always dreamed of living here, in an Airstream near the Rio Grande. Except his body was never found. So, I followed his suggestion and moved here in the hopes that he was alive and waiting for me. But, he wasn’t waiting. Because he’s dead.”

Summarizing had never been her strong suit.

“Sorry to hear that,” the woman said. Why did she look so radiant and joyful? It was more than just her skin. Was it her chin? No—it was her mouth. The corners of her mouth turned up rather than down. Mona touched her own mouth. Her corners did not turn up.

“Is there a new Mr. Disgusting in your life?” She seemed to relish saying the word “disgusting.” “A New Mexican version?”

“I met someone a few months ago,” Mona said. “We flirted for fifteen minutes and it felt like a carnival ride, and then he vanished and I never saw him again. I didn’t catch his name, so in my mind I just refer to him as Dark.”

“Was he black?” the woman asked.

Was she joking? There were no black people in Taos.

“It was more of a personality thing,” Mona explained. “He wasn’t dark as in dreary, though. His darkness had a spark. It had a charge you could feel on your skin.”

“A dark spark,” the woman said. “I know the type.”

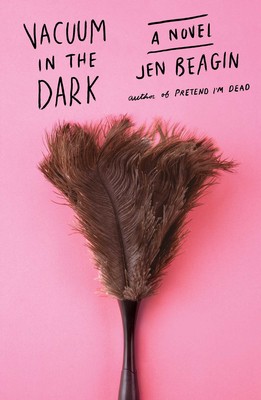

__________________________________

From Vacuum in the Dark. Used with permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2019 by Jen Beagin.