The Muse in Winter

For thirty years, Anja has lived in his city. Now that he is gone, it turns to her an unfamiliar face. From the safety of the train, behind the thick-paned window, she recoils from its lopsided mouth, its filthy eyes. When she steps off the platform, it looks away in recrimination. Hatching a plan. Lying in wait. She would apologize or confess if she had cause, but she has no cause. What is the old saying? The heart takes no commands. She loved him, but she has never loved where he brought her.

She climbs the hill toward the house they shared. She is coming from a meeting at the university, which has taken the last of his papers. In her bag is a letter on heavy paper signed by the chairman of the board of trustees, explaining the terms of the transaction. It has taken three weeks to pack up his effects, and now his books are all that remain of him in their house. To Goodwill went his clothes, to his daughter in Leiden the few letters and photographs he’d saved at Anja’s insistence.

Pieter Meisner was a man entirely devoid of sentiment, and she was, if not his wife, the partner of his mind. Vacated by his body, she and their rooms have suffered little substantive change. The house had no claim on his body, and so it does not register the absence of his breath or his excretions or the touch of his tremulous fingers. They miss his ferocious brain, that generator humming all the days and nights, emitting its invisible vibrating vectors. She would vibrate, too, and return her own waves, the two of them hurling energy back and forth at each other even as they slept. Mornings they woke already buzzing.

How still she feels now.

But the city. The city grieves all of him, and has shifted from its halfhearted attempt to woo her to its campaign for revenge. The brick buildings narrow wrathfully as she walks between them on her way up the hill. If she does not quicken her pace, reach the square at the end of the block, the walls will squeeze her last breath out of her. Already she has slipped once and fallen on the cobblestones, spilling her bag of oranges, where they sizzled and foamed in the burning snow until, stumbling to her feet, she stuffed them back in the bag. She hurries on, her gaze fixed on the broad square, asking humbly, silently, for the protection of the dogs and the Jamaican nannies and their shrieking charges, but they cannot register her plea. She is just another rich old white lady carrying her groceries in a neighborhood of rich old white ladies busy with their projects.

The little peace in her life Anja has found in only two places: a crowd, or with him. Everything else—all that in-between—has bedeviled her since Italy brought her into being. Now she dreads the party of two, being seated across from any person who is not him, a woman especially, her hand clasped clammily in hers, her face beseeching, besieging, digging her hollow. There is equal terror in the party of three, in negotiating the conversation, steering it one way or the other, trying to ensure that no one stays too long in the cold. If she must choose, give her a movie set or a stage. Give her an audience of eager nameless strangers drinking her in. Or, best of all, these days, give her her empty rooms—two blocks past the square, one block north, almost there almost there—where she will be, if not admired, then, at the very least, safe.

She sees the young man on her front steps the moment she turns the corner, before he sees her. He rises at her approach. “You are Anja Bloom?” he asks.

Without meeting his eyes, she sets down the grocery bag and reaches into her purse for a pen. “You have something for me to sign?” For this reason alone, she should have kept her name out of the newspapers after Pieter’s death. Apparently, it has not been enough to answer by hand the letters her manager forwards her each quarter, to autograph head shots and film stills, to, once, in a rare flare-up of sentimentality, walk to the hospital on the other side of the hill to grant the dying wish of a man in his fifties wasting away in his bed. Now, because she was too weak to believe Pieter would ever die, and prepared not at all for the aftermath of his going, she will be compelled to entertain in her front yard actors and film students and all other manner of the curious and needy, until she decides on her next and final city.

But this young man produces no yellowing playbill, no decades-old glossy photo bought from one of those vintage shops at the bottom of the hill. “I am not a regular celebrity fan,” he says, with an attitude and affect she recognizes but cannot quite place. The most she can identify is that unmistakable mark of the Italian man: bold imperiousness shot through with shame. “Le mie condoglianze per la perdita di suo marito,” he says, with careful formality. Not a Sicilian, for sure. A Florentine, maybe. Educated. Or a skilled impostor.

“Common-law,” she says, studying his face.

“My father was Sandro Nencini,” he says in English. “That is my name also.”

The lone tree in her yard shakes its fists at her. She picks up her bag and shoves it into the arms of the young man. “We can talk upstairs,” she says, and, as soon as they are inside, she slams the front door and turns the lock. Breathes deeply. Here, finally, in the stairwell, her back against the solid wall, she can gulp the sweet life-giving air.

His boots drip brown salt on the living room rug. “Please,” she says, motioning to remove them. The west-facing windows drown him in light. His large and ungainly feet, sheathed in multiple pairs of multicolored woolen socks, are incongruous with his slender body. He unwraps his scarf to reveal a pleasing mutation of his father’s face, one made kinder by a softened Roman nose and blunted cheekbones. His mother must have been a girl from the country, plump and sweet and adoring. Likely against her wishes, he has decorated himself with a beard and mustache and the feminizing long hair favored by the youth of film departments since her day.

He is very sorry to bother her, he says, helping himself to Pieter’s leather chair. The last thing he wants to do is to trouble her in her grief, especially given its recent onset, but he has come because he hopes he might be of some comfort, or at least an agreeable distraction, or maybe even a happy walk down what he calls—with no apparent discomfort with the cliché—“Memory Lane.” He couldn’t resist the chance to see her in person, he says, once he read the name Anja Bloom in Professor Meisner’s obituary in his university’s newspaper. Who would expect to find such a name in such a place, dropped into the history of the great astronomer’s life as casually and matter-of-factly as one of his distant stars? But of course, he says, in a phrase he must have scripted, she was one of Meisner’s stars, too. Did people tell her that all the time?

Once, yes.

“No,” she says.

__________________________________

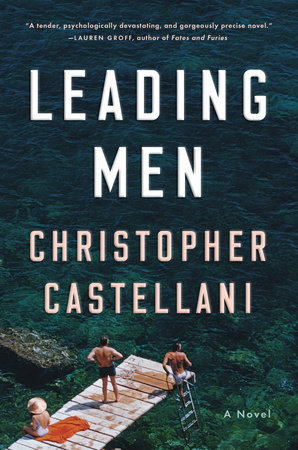

From Leading Men by Christopher Castellani, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Castellani.