An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence

by Dana Grigorcea

At the Festival Neue Literatur, A Crash Course in Contemporary German Literature

Dana Grigorcea will take part in this year’s Festival Neue Literatur, March 28–31. To reserve your seat, click here. The following was translated by Alta L. Price.

__________________________________

In the morning I called my parents in Nice again. They have guests and are tipsy. ‘C’est notre fille, qui est rétourné à Bucharest,’ I hear my father say.

‘Ah, oh,’ the guests reply.

‘C’est romantique!’ my mother says, and they all laugh approvingly, ‘C’est romantique!’

I laughed along, but just cannot get used to how loud they are now. During the long summer nights of my childhood, when we had friends over and sat under the grape arbor beside the house, they always spoke softly, almost silently, so that even someone on the second floor would think we were completely silent, or that no one was there. Had there been a spy, he’d have had a heart attack when one of us used the soda siphon to replenish our spritzer. Back then the nights were so dark that I couldn’t tell whether I was still under the arbor or somewhere else, whether my eyes were open or closed, whether I was actually moving or just thinking of moving. At the time I enjoyed that kind of confusion, a staggering feeling of weightlessness—indeed, when I think back, I recall a primal blamelessness, an almost instinctive feeling of innocence.

The scent of linden continues its spread through the nighttime air, following me to bed, where we lie motionless—two warm bodies, unable to cool down in this heat. The sky remains bright and starless. Through the window, on a nearby hill, looms the brightly lit People’s House, surrounded by seagulls floating slowly up and down on the air as if in a snow globe. 5,100 rooms, 200 toilets, 480 chandeliers, 150,000 incandescent bulbs—I count it all and fall asleep.

•••••••

Outside, her many dogs bark themselves hoarse against the corrugated metal fence. They’re probably not the dogs I used to hear, but they sound just like they did before, way back when. We talk a lot about my time in Zurich. ‘Zurich,’ Mrs. Miclescu says with properly pursed lips—she has been there, too, and has fond memories of the Confiserie Sprüngli on Parade Square.

I usually sat upstairs at a table by the window, to the left of the entrance, with my bank coworkers; we’d eat Birchermüesli with wild berries and whipped cream, and play I spy. ‘I spy with my little eye something you can’t see, it’s far underground, straight below the tram stop on the 8 line, headed toward Bellevue.’ And then came the questions, ‘Is it paper, and does it belong to an assassinated Eastern European dictator?’ ‘Is it sparkling, and does it belong to the widow of an Arab despot?’ ‘Is it a love letter?’ ‘Is it a gold trophy from the World Cup?’ I don’t know who actually knew the safe deposit box contents and who was bluffing, but in any case it was more fun than our corporate team-building retreats in Saint Moritz.

One of my coworkers, Daniel, came from a venerable family and, just like his father and grandfather, was a member of the Kämbel Guild. Each spring he’d dress up like a Bedouin and ride through the city as part of his guild’s procession for the Sechseläuten Parade, while high-society ladies tossed them flowers. Once, Daniel told me that he’d like to rob a bank, ideally the bank we worked at, in his Bedouin costume. Instead, he asked his cousin to rent a safe deposit box so he could open it whenever he wanted, using the bank’s back-up key.

‘This is the safe deposit box of Cupid, god of love,’ he decreed, offering to open it for me.

He had put all sorts of useless stuff in it—a swan’s feather, a marble, a ballpoint pen, dried flowers. When he wanted to impress one of his countless girlfriends, he’d lead her into the vault and open the safe deposit box, about which he had woven an elaborate story. He’d then let her take out these cheap objects, about which he had also spun tall tales, and hold them in her hand. Or not.

‘He’s like my Dinu,’ comments Madame Miclescu.

‘He looked a lot like him, too,’ I admit.

Daniel was my closest coworker, the one I could call in the middle of the night to come with me for a walk.

‘This flexibility is a sign of my fickle nature,’ he said, and I shouldn’t read anything else into it.

He lived next to the Supreme Court, where there were so many chestnut trees that I thought I was back in Cotroceni, on Heroes’ Boulevard. That’s what I liked so much about Zurich: I recognized places I had never been to before. It often felt like my Bucharest, but not quite the same—not the one in which I only knew a few streets and neighbourhoods, but the one I had always imagined: my stairwell with its pent-up silence and heavy entryway door with the creaky lion’s-head door knocker; the angle of the raking moonlight, which cast the geometry of the street into high relief; the little starling whose call mimicked barking, all night; the engine that refused to start, its rattle reverberating down the entire length of the street; all it took was a whiff and suddenly the temperature would change along the way, the scent of a lilac shrub would send me down a lane I normally wouldn’t have taken, were it not for the fact that it felt like part of the winding lanes I’d already started down in Bucharest; I went onward, through a passageway, and was suddenly strolling down the long corridor of Mémé’s divvied-up apartment, towards the bathroom she shared with three or four other families; taking my bath in its large zinc claw-footed tub, I’d sail the seven seas alongside the glorious Captain Botev.

We always ended up at the last stop, in Bellevue Square, and everyone agreed, ‘Too bad everything is closed, otherwise we could’ve had another nightcap!’

•••••••

He wanted to stand on a balcony and look out onto a grand boulevard. It was to be as massive as the one in Beijing or, even better, the one in Paris—a Romanian Champs-Élysées to replace the old boyars’ houses with their rotten roofs and unkempt gardens and winding old alleyways, where epidemics could break out at any moment. And so the entire city quarter of Uranus, atop Arsenal Hill, was demolished, whereupon the city’s twenty-eight-year-old chief architect—whose thesis had been devoted to the ‘urbanization of fallow lots’—gave her comrades the good news that they now had free space to work with, an area ‘as big as Venice’.

‘As big as Venice!’ one comrade or another must have swooned, ‘Venice!’

‘Bucharest’s Champs-Élysées’ had been known—or, more accurately, not known—as the Boulevard of Socialist Victory. It was slightly shorter than its Parisian forerunner, but made up for it by being a full eight metres wider.

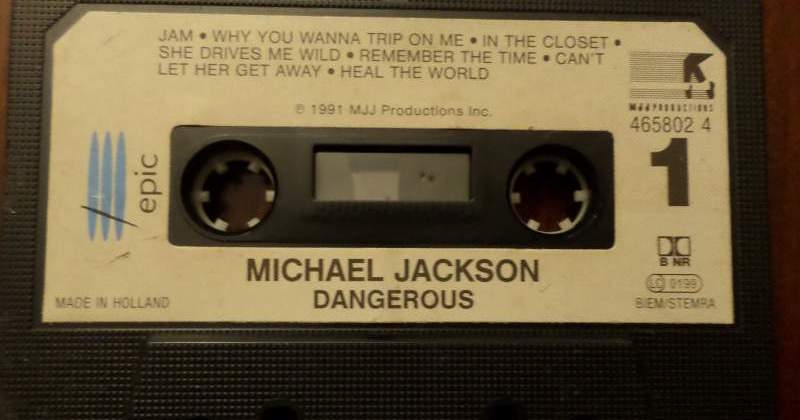

Nicolae Ceaușescu never had the chance to bow solemnly down from that balcony, so Michael Jackson did it in his stead, complete with glittering white glove. This was three years after Ceaușescu’s execution, during Michael’s Dangerous World Tour.

Back then hardly anyone left home without their personal copy of his Dangerous cassette—people carried them around just like the Chinese kept Mao’s ‘Little Red Book’ on hand during the Cultural Revolution. Everyone who owned a cassette player, like we did, would play ‘Jackson Poker’. You’d take a pencil or your finger and spin the tape to a random spot. Each player then had to guess what Michael would be singing when the music resumed. After everyone had placed their bets, the cassette was pushed into the recorder, and the person whose guess was closest won the round.

I never knew

But I was living in vain

She called my house

She said you know my name . . .

I had two copies of the Dangerous cassette. I listened to one and kept the other hidden in a safe place, in case the first one broke. When CDs came along, my father bought me the album on CD, in case we ever managed to buy a CD player.

When it was announced that Michael would be brought directly to the People’s House upon landing in Bucharest, I was one of the seventy thousand fans who, under the dark of night, pushed their way into the concrete gorge between the nearby residential blocks, an area known as Via Mala. Before us loomed the steep rock wall of the monstrous building, still under construction. It, too, could have been a night of sorts—a black, starless night, behind which one would find only wasteland and fallow terrain. For the first time, I now stood in front of this building, a massif I had only ever seen at a distance, from the window on Dr. Joseph Lister Street. And I probably never would have come here if it weren’t for Michael.

There were only a few sporadic shouts until the helicopters showed up, piercing the night with cones of light. The crowd’s shouts grew, ‘Michaaael, Miiichaaael,’ ropes were dropped from the helicopters, and everyone looked up to see if Michael was going to slide down to us amid the relentless autumn rain.

‘Is that him?’

‘That has to be him.’

But there was no one there.

We sang his songs to him, all mixed up. Sometimes a song sprang up from the back of the crowd and swept over us like a wave, bringing everyone’s voice upward and forward:

And it doesn’t seem to matter

And it doesn’t seem right

’cause the will has brought

No fortune

Still I cry alone at night

Don’t you judge of my composure

’cause I’m lying to myself

And the reason why she left me

Did she find in someone else?

And then another song welled up, initially sweeping the first one away, then bringing it back. This one was about love and betrayal, but above all betrayal, and everyone sang in unison:

(Who is it?)

Is it a friend of mine?

(Who is it?)

Is it my brother?

(Who is it?)

Somebody hurt my soul, now

(Who is it?)

I can’t take it ’cause I’m lonely.

Out of nowhere the night exploded before us, with a roar and apocalyptic fireworks all around the People’s House.

‘It’s burning,’ a few people cried out, fascinated, ‘he’s going to burn it all down.’

The sound of sirens struck us from all sides.

There we stood at the foot of Arsenal Hill, mythical gathering place of ungodly might, a steaming mass of human beings, drenched to the bone yet strengthened, blessed by the suffering of our ancestors, the chosen few who’d experience the end of it all, the ultimate, decisive battle prophesied in the Book of Revelation. ‘And he gathered them together into a place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon.’

‘Michael, Michael,’ we called out to our archangel.

And when the entire People’s House had disappeared behind fire and smoke, someone shouted, ‘Down with the nomenklatura!’ Or it simply came over us all, and everybody began chanting, ‘Down with the nomenklatura’!

‘Free-dom, free-dom!’

Everyone stretched their arms out into the rain, their fingers forming the victory sign—much like the one democrats had flashed a year before, but now with index-finger and thumbs, no longer the V-sign made with the index and middle fingers used in the so-called revolution, since the nomenklatura’s cruel, gruesome spectacle had made us out to be the suckers.

Once the smoke had settled, washed away by the rain, we had a clear view of what was once the mere People’s House, and now revealed itself, in blue contours, to be the Heavenly People’s House, the House of all God’s People.

Heal the worldMake it a better placeFor you and for meAnd the entire human race . . .

A bunch of light beams came together on the balcony of the People’s House, where a small figure stood and waved. ‘Huuuh,’ Michael shouted into the microphone, ‘huuh’!

Two large screens flashed in the night, each showing an oversized Michael Jackson in the red-and-blue officer’s uniform of the royal guard, complete with golden cords. If you check the history books, you’ll see that it was exactly like King Charles II’s gala uniform, just without the fancy white-tufted cap. Instead, he wore a black hat and mirrored aviator glasses in which the entire enormous square was reflected, teeming with innumerable teeny dots.

‘Hello, Budapest!’ Michael Jackson shouted. ‘I love you!’

It seemed as if, in the blink of an eye, the rain had stopped. Or the raindrops were suddenly stuck, hovering mid-air, just like the surrounding smoke. Dead silence. The End.

•••••••

I became a Pioneer of the Fatherland when I was ten years old, on a cold autumn day, or maybe a cold spring day—in any case, it was cold, and we weren’t allowed to put a jacket on over our snow-white pioneers’ blouses so they wouldn’t look all wrinkled at the big ceremony. The day had begun badly, because my red carnation had been swiftly beheaded by one of my fellow pioneers. He was small and graceful, but his parents sent him to karate. He was showing off his flying kick, and my carnation happened to be in the way. I was left with only the stalk, so I could’ve dueled with a fellow pioneer who also had only the stalk, but everyone else’s carnations were still intact.

So I had to stand in the last row when we lined up for the patriotic song, hidden back where nobody would see that I didn’t have a flower. It wouldn’t have been so bad had the walls of the old prison not been so cold—the celebration was held in the ruins of Doftana prison, not far from Bucharest, where Ceaușescu and his predecessor Gheorghiu-Dej had been imprisoned, as had the grandfather of one of my schoolmates, a fat blonde named Ileana. She was named after Princess Ileana of Romania, with whom her grandfather—despite his perfunctory communism, or perhaps precisely because of it—supposedly had an affair.

After a dress rehearsal of the ceremony in which we all received our official red ties, we were allowed to break for a short picnic on the lawn. The ground was cold and wet, and we spent so much time in vain, and covered so much ground searching for a suitable spot to sit, that we unexpectedly found ourselves back inside the prison walls, in a cellblock. We played catch, and then hide-and-seek, until Virgil called us. He had found iron handcuffs chained to the wall in one of the cells.

‘Do you guys think they’re real?’

We took a closer look—they seemed pretty ancient, given how rusty they were.

At the time we were all entranced by Alexandre Dumas’s novel The Count of Monte Cristo, and between classes we’d excitedly discuss the adventurous escape of the innocent prisoner who then appeared before his tormentors as the avenging angel. These discussions usually escalated into major disagreements, because each of us had our own ideas about how the story went, which led us to deduce that everyone else somehow had the wrong idea. Dumas books had to be reserved from the school library far in advance. Their good condition attested to the high value their readers ascribed to them. When my turn came, I, too, covered the book in a newspaper dust jacket, and paged through it as if poring over a priceless manuscript. But even then I couldn’t help scraping the little bits of wood out of the paper, and as those bits came off the surface a word here and a word there invariably came with them, unintentionally making minor changes to the book’s plot. Consequently, I left my own impression on these heroic stories, as I liked to imagine during the many nights spent secretly reading by flashlight under the blankets. The text on the other side of the page sometimes came through the brown paper, which made reading it much more difficult. The tedious process of deciphering each word made me feel like the first-ever, specially chosen reader. Sometimes I even tried to read the other side without turning the page, which meant reading in reverse, in order to anticipate the thickening plot. I always read in secret, hiding the books from my mother, who didn’t want me to bring any library books home—you never knew whether the previous reader had succumbed to tuberculosis or some other contagion. For every page I read, I was ready to pay the highest price, my very life, which I figured was what made me truly worthy of encountering the heroes and martyrs in such stories.

‘Let’s play with the handcuffs,’ someone suggested, and then everyone wanted to be the noble inmate. As fate would have it, however, only Virgil’s delicate wrists fit into the already closed handcuffs.

And who could the rest of us be? We all disagreed.

‘You all can be my guards.’

But that was no fun, so we decided to be his evil torturers.

‘And then we can switch’, said Virgil in a conciliatory tone, as we left him in his cell and went out to fetch our instruments of torture—pointy sticks to poke and prod him, big stones to smash his bones, and then all sorts of wildflowers we could say were poisonous, and I even found a snakeskin, which excited us all. We held it up against the weak sun, studying its fine patterns until our comrade teacher found us. ‘Can’t you hear when someone’s calling you?’

She was out of breath and close to tears. I don’t know why the ceremony had to start so punctually, there was no one out in this wilderness but us, her, and a comrade inspector, who was quietly playing tric-trac with the bus driver. ‘Go on, run to the entrance wall and line up, quick,’ she commanded, but on the way back we remembered Virgil. And then something funny happened—we had forgotten which cell he was in, and right before our eyes the cellblock grew increasingly labyrinthine. We wanted to call out to Virgil, but our comrade teacher was afraid the comrade inspector would hear us and realise that not everything was going according to plan, and that we weren’t a collective worthy of wearing the red tie, but just ‘a bunch of wretched losers’. ‘Go now, but keep quiet’, she finally said, and we ran from cell to cell whispering, ‘Virgil, are you there?’, only to then shout loudly over the walls, ‘He’s not here’, and then, ‘Not here, either’!

As I remember it, all of a sudden it was dark, clouds had blown in or night had unexpectedly fallen. When we found Virgil we noticed only from his voice that he had been crying. He could no longer pull his hands out of the handcuffs. ‘Make your hands small’, commanded our comrade teacher, but no one knew quite how that was supposed to work.

She let out a sigh and said, ‘Children, children—why can’t you just behave’?

Then she took off the bunches of bracelets she always wore, which clattered when she wrote on the blackboard and conducted chorus, so that all the ‘big kids’ said ‘Man oh man, we’d have loved to be lucky enough to have such a modern comrade’. Ileana was allowed to hold all the bracelets, and she was bursting with pride.

‘Come on’, said our comrade teacher, and began pulling on Virgil’s arms with all her might. ‘Make one peep and you’ll regret it’, she added for good measure, but his little hands didn’t come out, not even when she spat on his wrists to make the handcuffs slide more easily.

‘Do you want to rest for a minute, and we’ll take over for you?’ Ileana asked in her sing-songy voice, but our comrade teacher paid no attention, because she was busy rolling up Virgil’s sleeves so they wouldn’t get bloodied. His wrists were badly abraded.

‘And now they’re swelling up, too’, said our comrade teacher. When she thought she heard a giggle, she shot back at us, ‘You little shitheads’. She was on the brink of tears, ‘Unworthy! You’re all totally unworthy of the red tie’!

She asked for a clean handkerchief.

‘Grab my bag’, she told Ileana, whose stiff arms were straight out and still holding the many bracelets in her hands, but I had already pulled my bag over. ‘Here, take my handkerchief—the edges smell of eau de Cologne, but it’s clean.’ Our comrade teacher then rolled it up and ordered Virgil to bite down on it as hard as he could, so he wouldn’t feel the pain as much. ‘As hard as you can’, repeated Ileana, ostensibly out of concern for Virgil.

And then our comrade teacher grabbed Virgil’s arms, pulled and pulled, and his eyes nearly popped right out of their sockets. ‘You’re almost there’, said Ileana, and our comrade teacher braced herself against the wall behind Virgil with both legs, yanking harder. When even that didn’t work, she gave up and let Virgil—whose arms appeared as if they’d grown out of the same wall they now looked nailed to—slump into a heap on the floor. And then she took it out on us, ‘Miserable miscreants, go to hell, just hang yourselves with your shitty red ties, why don’t you? Shitty children! Shitty little shits! This shit sucks’!

After this fit she quickly regained her composure, rummaged through her bag, and pulled out a little blue container labeled ‘Nivea’.

‘What’s that’? Ileana asked in her sing-songy voice.

‘A medicinal cream’, said our comrade teacher, ‘can’t you see he’s bleeding?’

She spread the cream on Virgil’s hands and wrists, and with all her strength tried yet again to pull him out of the handcuffs. When that didn’t work, she held on to his limp body and lifted her legs off the floor. A few years ago, I saw a shaky film clip of a woman in Iraq who did the same thing with a hanged man, so he would die faster and suffer less.

Virgil wasn’t moving, but couldn’t be freed from the handcuffs either, so our comrade teacher put all her bracelets on again and led us back. ‘Sing as loud as you can,’ she commanded us, in case Virgil happened to wake up and start screaming. We left him there like that, my handkerchief still in his mouth.

I sang loudly, not because I wanted to follow orders but because I was intent on outsinging the overbearing Ileana. And so I was selected—the comrade inspector came to me after the ceremony in which we all got our red ties and said, ‘Have you ever dreamed of giving flowers to our supreme comrades’? Whereupon our comrade teacher burst into tears and hugged me.

Then she invited all the other children to hug me, first Ileana, commandant of our troop division, who was quite confused by this unexpected outcome, and then the girl who was commandant of the window row, because I sat in the row of desks closest to the window at school, and then the other commandants, too, of the door row and the two middle rows. The comrade inspector laughed and said, ‘Are there only girl commandants in your class’? Our comrade teacher cheerfully replied that the top students were always girls, and then the comrade inspector said something like, ‘Girls are always the best, even later’. She laughed the entire bus trip back to Bucharest, and because the comrade inspector accompanied us, we couldn’t go back to get Virgil.

I can’t quite remember exactly how the rest of it went, or I’ve forgotten the order of events at least, but I do know that first of all my parents congratulated me and then, when we were on an afternoon walk and I noticed there was no one in sight, I asked them to tell me the truth. ‘Which truth?’ ‘You don’t like him.’ My mother looked at me, horrified, ‘You mean our supreme comrade’? And then she slapped me, ‘How could you say such a stupid thing?’ and ran home howling.

Only later did I learn that my parents had separated for a bit, for that very reason. I had been sent away for a while, to undergo some medical examinations, so I hadn’t known at the time. But I met a bunch of nice nurses who were convinced I would become a radio star on the show Sing Song Minisong, and travel to Budapest and Prague, and maybe even the GDR. And another comrade class-leader lady also visited me a lot, bringing me sweets and telling me about Mother—that is, our supreme mother, mother of all the people, who liked being addressed as ‘Mother’. ‘Don’t worry, she’s very kind, just like a normal mother, even better.’ This mother’s picture hung in my room, she was young and beautiful as a fairy, with lovely hair and big, bright eyes.

And then came the big day. I got a huge bouquet of red roses or tulips, but I’ve forgotten everything, all the children who were there, and all the songs we sang, and whether I even opened my mouth to really sing at all or just moved my lips like I did at school, simply because it amused Mémé when I told her about it afterward. ‘Mémé, last year I even imitated animal sounds during the anthem. The blonde girl, Ileana, told on me, but our comrade teacher asked me if it was so, and I said no.’ Mémé laughed and said, ‘Oh, that must’ve driven Ileana mad’.

But the reality was different, I had received a royal walloping from the entire class. Our comrade teacher had held me and walked me past every fellow student, and all my comrade classmates were allowed to hit me as hard as they could. On that day all my friendships ended, even my friendship with little Virgil, who continued protesting that he had only made it look as if he had hit me, and not even with all his strength. ‘I’ll bet you want to see what it’s like when I hit you as hard as I can, huh’? he threatened, as I ‘continued acting’ as if I were offended, or so he claimed.

But now I was the one who was allowed to meet the supreme comrades, and I climbed the stairs to steady applause, clap-clap-clap, clap-clap-clap. The sound propelled me forward like a strong wind at my back, I teared up, and everyone I passed gave me a pat on the shoulder. ‘Bravo, child’, ‘bravo’, and ‘bravo, you are the future’. And then the voices of a children’s choir rose from somewhere, singing ‘When we’re no longer children, we’ll all lend a hand’. A sea of colourful flags fluttered over the whole scene, like millions of colourful birds, before unexpectedly freezing in front of the blood-red carpet, forming the exact shape of my bouquet.

Then there was a long silence, no motion whatsoever as far as the eye could see. It was as if I were suddenly all alone, and all the people around me were dolls.

‘Is this bouquet for me?’ asked an old woman with a potato nose.

‘No’, I said.

‘For whom is it, then?’

Out of the corner of my eye I looked toward the comrade class-leader lady, who gazed into the distance with unbridled joy.

‘It is for me’, said the old woman with the potato nose.

‘It’s not for you, because it’s for my mother!’

‘For your mother?’ the old woman asked with an evil grin, ‘And where is your mother?’

I looked around, but everything was frozen stiff.

‘She’s coming’, I said, to stall the old woman until help came.

But the old woman had already grabbed the bunch of flowers and was trying to pull it from my hands. I held on with all my strength. And then came the deafening noise, the applause, and thousands of comrades chanted and waved huge pictures of our dear Mother overhead, as she briefly continued to stare at me.

I stayed on the grandstand all afternoon, since the comrade class-leader lady had begged me to stay by the old woman with the potato nose. ‘Look what lovely braids you have, and such big pom-pom hair ties’, she said to me, ‘have you ever seen such big pom-poms? And you know what? We’ll wait until the end, and then we’ll ask if you can take the pom-poms home with you.’ So apparently I stayed there, shaking my head the entire time so that my braids waved, and they even saw me on TV. By then my mother had already returned home, and my parents watched the whole thing on Rapineau’s TV, with its three-colour layer of film, alongside a bunch of friends and neighbours. ‘What colour was my bouquet’? I asked. My father laughed with pride, and said, ‘Blue’.

__________________________________

About the author

Dana Grigorcea was born in 1979 in Bucharest. She studied German and Dutch philology in Bucharest and Brussels, Film and Theatre Direction in Brussels, and Journalism in Krems. Grigorcea was awarded the 3sat Prize in Klagenfurt at the Ingeborg Bachmann competition 2015 for An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence. Her debut novel, Baba Rada. Life is Temporary and So is The Hair on Your Head has been awarded with the Swiss Literary Pearl 2011. After living in Germany and Austria for many years, Dana Grigorcea now lives in Zurich with her family.

Previous Article

The Storytellerby Pierre Jarawan

Next Article

Everything is Still Possible Hereby Gianna Molinari