On the outskirts of the city, I found a truck stop and an A&W. I parked the truck as far away as I could get from the glaring neon sign that lit up the parking lot. I still had a few hours to go until I could drop the buffalo off in the park. There was dried saliva on my cheek where the dead man had licked it. I could feel myself covered in the blood and shit that had exploded out of his intestine. But when I looked at myself in the truck cab mirror, I didn’t see anything. The taste and smell lingered on me, though, and I knew if I didn’t clean up, it would never leave. I thought about eating something; it had been hours, probably, since the banana and bannock with chokecherry jam I’d taken from my parents’ place when I left this morning. A lifetime ago.

Inside the truck stop, a table of four sloppy white men wearing crusty, wrinkled sweatpants and stained t-shirts stared at me as I walked through the door. Their patchy beards holding mayo and other condiments, and the table covered in the remains of burgers, leftover fries, chicken bones, used ketchup packets, and pop cups. I avoided their leers. They were straining, trying to catch my eye. One of the guys leaned way over so I had to turn sideways to avoid touching him as I went by. I wanted to drag his tongue out of his mouth and tie it around a urinal puck. But I kept going, eyes fixed on the prize of a women’s washroom that probably wasn’t used that often. I wished I still had the rifle. So if one of them thought about following me in, I could turn around and put him through the sink. All I wanted was cold, crisp water on my face. To wash away the past few hours.

The prize of the women’s washroom didn’t play out. A clogged toilet that, instead of plunging, people had shit on top of until shit filled the bowl. I kicked the lid closed with my boot so I wouldn’t have to look at it. Toilet paper was strewn everywhere, and it looked like people had begun pissing in a corner. Someone had used white-out or paint to cover all the graffiti but didn’t do anything after, so it just sat there in a different shade to the rest of the nicotine-yellow paint. Thankfully there was a paper towel dispenser in there and not an air dryer. I grabbed a handful of towels and wiped down the counter around the sink. Hot water started coming out of the tap, and I cupped my hands under it and then splashed the water all over my face. I grabbed more paper towels, wet them, and then scrubbed my cheek where the dead man had slobbered on me. I used the paper towel to clean where I thought his blood had stained my jeans. I really couldn’t tell with the dark denim, but I scrubbed anyway. I scrubbed everything. If I could have filled the sink up with water and then got in it like a child at bath time, I would have. My entire body ached to get clean, to soak, lay back, and sleep. Back at Auntie May’s, the first thing I’d do would be to take a long bath in a real tub loaded up with lavender scent from the endless vials she kept next to it.

“Two Teen Burgers, onion rings, and a large black coffee, please,” I ordered. The Filipina lady working the till smiled and put my order in.

“Wow, hungry lady for someone so skinny,” the trucker in line behind me said. “You better watch it, girly, or you’re going to get a big belly.” He started laughing. I ignored him and walked over to the side to wait for my order. I pulled out my phone and pretended to text someone.

“Five-piece Chubby Chicken meal and a Mama Burger,” the trucker ordered. “You know I like my mamas,” he added, then winked at the lady working the till. Then he turned to me. “Why don’t you sit that pretty little butt down and join me for supper?” “Sure!” I said. He looked startled. “Then, I’ll crawl under the table and suck your tiny little dick if I can find it.” His face dropped. My food came out. I grabbed the bag. “Go fuck yourself,” I said as I walked by him.

“Yeeeeoooooowww,” one of the truckers sitting at the table called out as I stepped through the doors and walked back to the truck. I checked on the buffalo. They seemed okay despite the dead one lying on the floor of the trailer. Maybe? What went through a bison’s skull, even? I used to think I knew a lot about bison. I used to think I knew a lot of things. The last few hours had torn that notion apart. Inside the truck, I unwrapped one of the burgers, pushed the lettuce back into place, and took a big bite. I didn’t taste anything. I took another big bite. My stomach clenched, and I set the burger back inside the brown paper bag. Grease from the onion rings was already sliming up the bottom of it. I grabbed one of them and ate it. It was just the fried dough, no onion inside of it. I started laughing. My granny was a lady who’d loved onions. She would eat them like apples, or cut them up and put them on white bread with bologna for a sandwich, or when she didn’t have any meat, just have a raw onion sandwich straight up. And she’d really loved onion rings. That was the treat we always brought her after she moved out of Pembina Creek and into a seniors’ building in the city. What I wouldn’t give to drive over to her little apartment, drop her off these onion rings, and drink tea with her into the late hours of the night. She passed away years ago. At least, it felt like years ago. I didn’t understand time anymore. She’d got sick, and then her memory had faded. I reached up and grabbed the little tanned-hide medicine bag that my father kept hanging from the rear-view mirror in the cab of the truck. Granny had made it for him. For his safety. She’d beaded a six-petal flower in blues, reds, and white on the brown hide. I moved my fingertips over the beads, learning the curves of each individual one.

Granny had tried to teach me how to bead. When I was a little kid, I would place the beads on the needle for her. That was my job, and I loved every minute of it. She would feed me homemade oatmeal cookies and cups of Labrador tea while I placed five yellow beads on the needle and then five more. I tried to anticipate the colours she would use, and eventually she started letting me pick the colours out. That was a big deal. I’d like to think that she passed down teachings or history lessons to me, but all I could remember was gossip. That lady had loved to gossip. She knew everything that was happening throughout Pembina Creek and some of the neighbouring reserves. She even knew what was going on with the family that had moved to the city. It didn’t matter if she didn’t have all the facts or had to make some of it up herself. She loved to tell a good story. There was no need for television or soap operas when her extensive Métis kinship network provided everything needed for entertainment. I couldn’t remember much about her own story, but I did know that her sister had chewed through husbands like a puppy with a stick.

I forced myself to finish one of the burgers. My head felt stronger and clearer. I had to figure out what to do with the dead bison. The worst thing would be to let all that meat and the hide spoil. I would never forgive myself if that happened. I could unload the live ones in the park and then drive back to my parents’ place and get my dad to help. But then he would wonder why there was a dead bison inside the trailer. Especially since I’d told him I needed the trailer to do a bit of contract work moving cows around for a friend’s family farm. That might seem a bit suspicious.

Plus, I didn’t want to get my parents involved. They had enough of their own troubles dealing with the shit of being prairie poor. The last thing either of them needed was to be an accessory to bison theft. And murder. I scrolled through the contacts on my phone. No one really stuck out. A few people from back in my activist days, maybe, though I didn’t know what kind of help they could offer, since most people had no idea how to drive a truck. Most had never hunted a grouse or even a deer, let alone a bison.

I turned the radio on. cbc News was in the middle of its hourly broadcast. More buffalo trouble on the prairies:

“An area golf course was shut down today after a herd of bison escaped from a ranch outside of Camrose sometime between last night and early this morning. They blocked traffic on Highway 833 before moving onto the Camrose golf course. City staff assisted by the local rancher are still working on rounding up the buffalo. People are asked to avoid the area until authorities tell them it’s safe. Meanwhile, back in Edmonton, protestors continue to block the entrance into Dawson Park. The protest movement is now calling itself sohkapiskisow paskwawimostos, which translates from the Cree to ‘Bison Strong.’ Local ally Erin Green has made shirts and bumper stickers with the hashtag #bisonstrong.

We have Erin with us in the studio here today . . . So, Erin, can you tell us a little bit about what you’re hoping to accomplish with your shirts and bumper stickers?”

“Well, first off, I’d like to acknowledge that I’m on Treaty 6 territory and the ancestral homeland of the Métis peoples.”

“Yes. We’d also like to acknowledge that. Thank you, Erin.”

“So you know, when I first saw the bison, I thought, ‘Oh my god, they must belong in the River Valley.’ This is, like, their home. And we took it from them. So, like, we should do everything that we can to help them stay here, you know?”

“Erin, can you tell us a little bit about where the proceeds from the Bison Strong sales are going?”

“From every shirt or sticker that’s sold, I’ll donate ten per cent back to the activist group. It’s my way of moving forward with reconciliation and letting the bison know that they have a home here.”

“Amazing work, Erin. And I’m sure the protestors thank you for your generosity.”

“No problem! Thank you for having me.”

“There you have it. You can get your stickers and shirts from bisonstrong.ca. I know I’m getting one.”

I switched the station to Windspeaker radio. They were playing Merle Haggard. It must have been the old country hour. I was surprised that Tyler hadn’t weaselled his way onto the radio, and that he wasn’t a part of that sticker and shirt thing. The name of the group sounded just like something he would have thought up. He would have told everyone that an Elder gave him the name in ceremony. But I know he would have just pulled the Cree dictionary app up on his phone and typed in the words “strong” and “bison.”

Fuck, I thought. That’s who I should call. I didn’t have his phone number in my contact list anymore. I tried to remember it. 780-967-something.

I downloaded Instagram. I hadn’t checked my account in months, maybe even a year. I knew he would be on it, though, looking for that instant gratification. He was always posting away and sliding into Instababes’ direct messages. Another system to give him the constant attention he needed. I typed in my username, maskotew—“prairie” in Cree. My password was the same for everything, ILAG8890—I Love Adam Gladue and then our birth years. A relic left over from my first email account and first boyfriend back in Pembina Creek. We broke up in Grade 11. But I kept the password.

I clicked open my messages. My inbox was full of invites to events, men trying to chat me up, white people asking for advice on reconciliation. All the shit that made me delete the app in the first place. I searched for Tyler’s account, TeeCardz. His profile picture was him holding a megaphone and standing on top of a barricade. That was from a few years back, when the railways were blockaded in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en. He was still skinny in the photo. I clicked the message button. We didn’t have any saved conversation history. That had long been deleted by one of us. I forgot who. I sent him a message:

Hey, I need to talk to you. Please call me asap.

Two hours later, he called. I was still sitting in the parking lot. “Hey,” I answered.

“What’s up? You pregnant?” he asked.

“You’re such a fucking asshole,” I said.

“Cause it’s not mine. We haven’t hooked up in like a year.”

“I’m not pregnant. Fuck you.” I tried my best to control my voice. Everything in me wanted to reach through the airwaves and strangle his fat neck.

“Oh . . . Did you want to come over then?” he asked. “I haven’t seen you in so long. It would be great to catch up.”

“I need your help,” I said.

“Pass.” He started laughing. “Wait, does it pay?”

“Nope. But I still need your help.”

“Why the fuck would I ever do that?” he said.

“Because without me, you wouldn’t be able to go around sticking your dick in all those white girls who want to get back at their racist daddies.”

He laughed again. “Grey, Grey, Grey.” I could tell he was amping himself up for one of his patronizing lectures. I wasn’t going to have any of that shit.

“Look, can you meet me at Terwillegar Park at one a.m.?”

“Fine.”

__________________________________

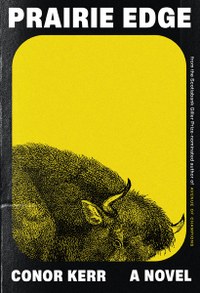

From Prairie Edge by Conor Kerr, published in the United States by the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2024 by Conor Kerr. All rights reserved.