Just thirty kilometres outside of Nairobi, off the Nakuru highway, the land becomes flatter and less populated. An unassuming field beyond Limuru gives way to several isolated buildings behind a rusty gate. This is Kamirithu Polytechnic, the present site of what more than two decades ago experienced one of the most important cultural revolutions on the African continent.

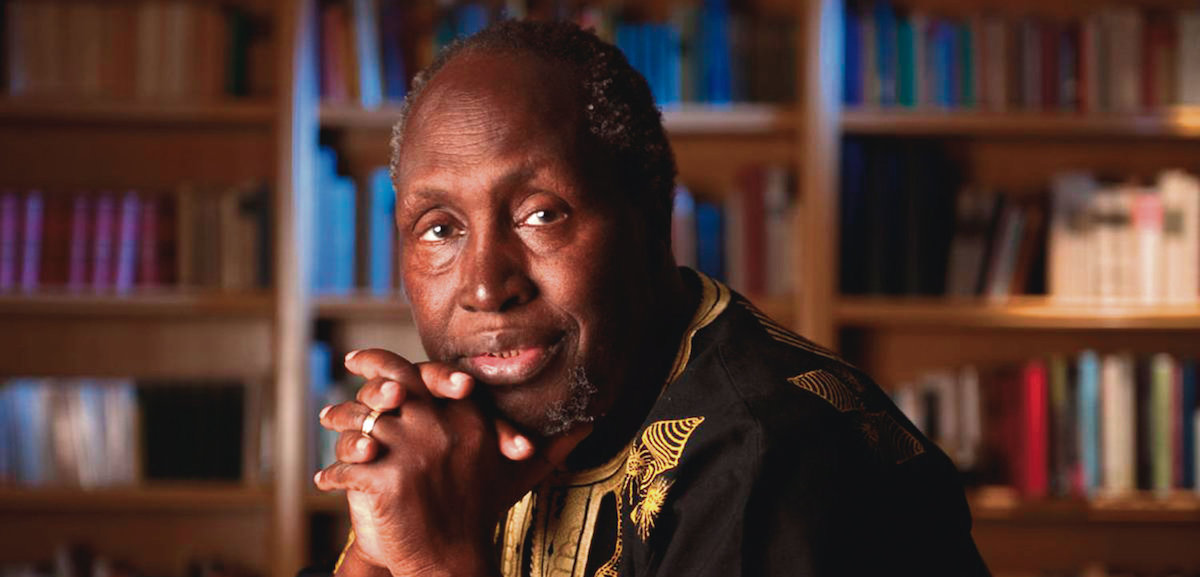

In 1976, locals from Kamirithu village approached Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who was born and still lived there, asking him whether he could help bring back to life their youth centre. Ngugi at the time was Chair of the Literature Department at the University of Nairobi. Soon, he and fellow writer Ngugi wa Mirii were scripting a play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want) which premiered at the Kamirithu Education and Cultural Centre’s open air theatre in 1977. The production was created with the community and set out to use only local resources: actors, stage managers and of course, the local language, Gikuyu. Notably Kamirithu the village had not only cultivated Ngugi’s writerly imagination (landscape features including Manguo marshes and the surrounding ridges feature prominently in his novels) but also had a historical trajectory that also inspired the writer’s early sense of political and economic injustice, starting off as a colonial labour reservoir when he was a child. Not surprisingly the new center was structured in way that addressed some of the concerns of Ngugi’s novels. Petals of Blood a novel which would be released the same year that Kamirithu featured its first play is preoccupied with history as a cycle of material exploitation depicted through its fictional setting Ilmorog and its evolution from village to large town after a national highway is built through it.

Today Kamirithu has become your standard peri-urban space (and it is off the Nairobi-Nakuru Highway, almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy projected in Petals of Blood. His description of Kamirithu in his prison diary, Detained has similar echoes to the new Ilmorog of Petals of Blood. Both settings show the long-term effects of what the writer has described as the politics of exploitation in African societies, dominated by neo-colonial elites and foreign Western interests. Instead of grass-thatched mud huts of Ngugi’s childhood you now have the ubiquitous mabati wooden sprawl that you find all over Kenya, creating something that is in-between the city concrete and the rustic; an aesthetic that has emerged from a struggling post-independence economy and astronomical population growth.

Within this context Kamirithu Educational and Cultural Centre emerged to become that rare phenomenon—not only a cultural but socio-political space and therefore the praxis for Ngugi’s ideas even more than his novels because of the involvement of the locals. Kenya’s political struggles have always been primarily been waged between elites in opposing camps headed by respective leaders playing tribal chieftains for their respective ethnic constituencies whose only options in the game of power are to play king-maker.

Kamirithu was a grassroots-based cultural awakening, an example of what the State has always willfully suppressed—the class dimension of Kenya’s politics. From it came the realization that when, and if, the revolution ever came to Kenya, it would not be through elite games but from an actualization of grassroots awareness of the country’s inequality of wealth. This possibly explains why state agents appeared at Kamirithu as it was about to release its first theatre production and closed down its activities subsequently jailing Ngugi. And that was not enough because later a state agents razed the open-air theatre the locals had built—to the ground.

Earlier this year when Ngugi’s son, writer Mukoma wa Ngugi, visited Kamirithu Polytechnic, the students and teachers he spoke with were ignorant of this history. When Mukoma told them about his father’s work with the Centre, the students asked him whether he had brought any books for them. This request for books rather than money possibly speaks to what Kamirithu had been trying to achieve—a local populace firmly in-charge of its own destiny. Ironically Kamirithu Polytechnic itself emerged from exactly what Ngugi and others had fought against, through a handout from then President Moi. After Kamirithu had been obliterated by state agents, the president, with a Machiavellian stroke, visited the area, shed tears at the poverty, and ordered a Polytechnic built. By then Ngugi had already been forced into exile swearing not to return while the Moi regime remained in power.

*

Ngugi’s vision—driven by the involvement of the people in political and social activities on their own terms exemplified by Kamirithu—might possibly explain why his recent returns to Kenya following his forced exile between 1982 and 2004 have not always been happy events. During his first visit back, Ngugi and his wife Njeeri were attacked at the Norfolk apartments where they were staying. Masked intruders forced themselves into their room and raped Njeeri, robbed them and put out cigarettes on Ngugi’s forehead.

Two days after the attack I attended an event at the Godown Arts Centre featuring Ngugi. Everyone was surprised when he showed up. There he sat before what was primarily an audience of artists. We were taken aback by the equanimity he spoke with. His voice had no trace of bitterness. Like many young aspiring writers present I was utterly horrified at what had taken place. It reminded all of us that the Kenya we thought we had left behind was still alive and well. It was an indictment for the whole of Kenya. The relationship between this attack, Ngugi’s writing and his politics continues to be a source of speculation.

As I was growing up in the 1980s and starting to read anything I could get my hands on, Ngugi was The Kenyan Writer.The Norfolk security guards were charged and later sentenced to death, but the courts dismissed any political motivation behind the attack. Ngugi in a later interview with Mayya Jaggi in the Guardian commented: “It wasn’t a simple robbery. It was political … We think there’s a bigger circle of forces—not just those who attacked us.”

What particularly struck me at the time was the bile in the perverse public reactions to the attack in the Kenyan dailies. The sheer animus in some of the theories included that Ngugi had joined Mungiki, a local militia, and then decided to leave and that this was a revenge attack. This was supposed to be a time of general euphoria following the 2002 elections after which the Moi regime had left after 24 years. At the time of the attack the general feeling was that the forces of Kenya’s sordid and macabre violent political history could never be quelled.

*

As I was growing up in the 1980s and starting to read anything I could get my hands on, Ngugi was The Kenyan Writer. And yet it was clear that he was perversely feared within a middle-class bourgeoisie who lacked the courage of his beliefs. I remember the snarky conversations of the adult relatives around me—how Ngugi and others were too much. Why could the writer not just be happy with all he had been blessed with? He was after all a University Don and was even allowed to import a Toyota without duty. Why could he not start a car importation business like many other lecturers?

I remember Detained on my father’s shelf when I was 11, next to the finance motivation books that were already the rage in Kenya. In my fertile imagination I was sure the book had been banned. The bright blue cover felt almost radioactive. I later learned that the book was never officially banned. That was never necessary—such was the power of the state in the 80s that it could easily declare Ngugi the devil in disguise and mainstream Kenya would believe that. And so there was a mass-internalization that he was someone with “dangerous” ideas. By then he had fled into exile and had also decided after Kamirithu and while still in jail that he would write his work in Gikuyu.

In 2010, when I was working as editor for Kwani Trust, we invited him to headline the Kwani? Litfest. In his keynote at the festival he entreated us, a younger generation of writers, to write in African languages rather than English. A few days later we went on a radio show together and I privately asked him afterwards what I needed to do because my Gikuyu was not strong enough to write in. He said with good-humored conviction that I had to learn. When I stressed that I did not think that Gikuyu would not capture the reality of growing up in Buru Buru, would not capture the Nairobi life that I was interested in writing and that was navigated through English, Kiswahili and Sheng, he shook his head insistently.

I did not tell him that his book Devil on the Cross was the first novel that I had read in which I recognized the Nairobi I had grown up in from its descriptions of the city centre through scenes on Ronald Ngala Street and Racecourse Road. I feared that he would ask me whether I had read the Gikuyu version Caitani Mutharabaini. Indeed I had never acknowledged this debt to him as a writer to anyone. Within the Kwani? community of writers at the time it was more fashionable to claim Meja Mwangi and his gritty River Road settings as influences. But after that visit many of us thawed from Ngugi’s warmth and generosity.

I began reading The Wizard of The Crow, which Ngugi had translated himself into English from the original Gikuyu Mrogi wa Kagogo. I started getting puzzled by some of the Gikuyu words included that did not seem very, well, Gikuyu. Is this the African language that Ngugi wanted all of us to write in? I sought out a linguistics scholar who told me that the origins of written Gikuyu lay in the translation of the Old Testament of the Bible. This had been done by Christian-trained Gikuyu clerks who did not necessarily speak, or understand Gikuyu, in its oral narrative roots as well as the elders who refused to engage with the new English missionaries.

The new written Gikuyu therefore might not have reflected the full cultural richness of the language. The scholar added that because of a flawed translation process there is something of the overtly literal about the written Gikuyu of the Old Testament. With this then becoming the default point of departure for all written Gikuyu, this then complicates attempts to write fiction in the language. I felt vindicated. Why would I seek to write in a written Gikuyu that was stilted?

A year later I was struggling with a novel I was writing, and in particular a section based in Muranga, Central Province where the reality of that world could only be told in Gikuyu. It suddenly hit me that I could not write the section in English unless I first imagined it in Gikuyu. It was only then I understood what Ngugi had been trying to do in The Wizard of the Crow with what felt like anglicized Gikuyu. I realized I had made the mistake of dismissing Ngugi’s message on writing in African languages by forcing a crude simplicity to it. I am not sure why I thought Ngugi meant that I had to learn that written Old Testament Gikuyu to write. Now looking at some of the Gikuyu used in The Wizard of The Crow, and struggling with the Muranga section of my novel in progress, I understood one had to approach one’s own language as a way of freeing up one’s imagination in ways that someone else’s language might not.

Those anglicized Gikuyu words in The Wizard of The Crow made me understand the world of the novel that their English equivalent could not. It sounded sweeter in Gikuyu as it always does. Ngugi taught me that I too had to find my own Gikuyu cosmological imaginary just as he had been striving to do for many years. In writing this part of the book I understood that English could only become mine if I was able to bend it to an honest imagination of the Muranga I was trying to capture. I rewrote that section my novel-in-progress in the Gikuyu I had heard as a child and only then could I re-imagine it in English.

And yet in a Kenya today with ever-rising inequality, a huge youth unemployment problem, Ngugi remains understandably more feted for his political ideas than for his writing craft. Beyond a generation born in the late 80s who lived during a time that could still be witnessed in Ngugi’s books and Kenyan academic circles, one feels that few know his work well. Because of this Ngugi at times feels untouched by time. Regurgitated discourse on Ngugi in Kenyan academic spaces might not have served him as their selected champion well. In addition, the deterioration of the Kenyan public education system over time and badly taught secondary school classes suggests that a whole generation has come to detest both literature, if not Ngugi who has been a staple of the education curriculum.

Now with a steadily growing youth-based grassroots anger at the state and its perpetual failed promises, Ngugi and others are being vindicated in the eyes of a younger generation.Kamirithu notwithstanding, I also find that many scholars and writers of my generation have succumbed to outlandish conspiracy theories and disparaging claims of the writer informed by the ethnic sensitive nature of Kenyan society post PEV (post elections violence in 2008). After those 2007 elections he was accused on Twitter of being a supporter of ethnic “cleansing” by a few keyboard warriors because he allegedly supported the incumbent, Mwai Kibaki.

I have been told many times that there is no reason that Ngugi should be more prominent than the late Grace Ogot, a Luo writer of his generation echoing the same kind of elite games that have characterized Kenyan politics since independence. It is not enough to just acknowledge that we are blessed to have both. Ngugi, it is even said, blocked Meja Mwangi from being taught at the University when he was head of department there. In Detained Ngugi has already written of a similar kind of ethnic chauvinism during his time there. Ngugi who was once enemy of the state has since entered what the late Binyavanga Wainaina in an editorial rant after the attack on Ngugi called “Pull Him Down” (PhD) Kenyan territory that fears success so much that it must tear apart those who achieve it. Wainaina wrote, “it is a measure of the power of Ngugi’s writing, and his politics, that people can take it so powerfully, so personally. For if so many are invoking their PHD status on him, he must truly be formidable.”

And while it is still hard to gauge what Ngugi means to a younger generation of Kenyan writers—those now in their twenties, a recent event at Nairobi based-Pawa 254 suggests that they might be more amenable to what he was saying to me about language. There, Ngugi appeared in 2016 and staged an event with Jalada Africa, a new generation Nairobi-based pan-African writers’ collective. Jalada Africa was celebrating the work of Ngugi wa Thiong’o through a translation of a short story, or rather fable, by the writer titled Ituĩka Rĩa Mũrũngarũ: Kana Kĩrĩa Gĩtũmaga Andũ Mathiĩ Marũngiĩ (The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright).

Ngugi explained how this had come to be. He had revived a short story he had written decades ago. Jalada translated the story into more than 50 languages and counting and it went viral. This ability to work with new younger literary players like Jalada represents the Ngugi who more than two decades ago recognized the power of the grassroots through Kamirithu. The event brought together different generations with different strengths. Ngugi was in Kenya to receive yet another honorary doctorate from a Kenyan University the next day but he said what Jalada had done for his story was as great an honor as the degree he would receive the next day. The University of Nairobi where Ngugi and others held debates on changing the name of the English Department to Literature decades ago is still yet to recognize him in similar ways.

Ngugi continues to write and appear publicly with continued optimism; increased visits back to Kenya and more importantly the release of new material through his memoirs has opened his work beyond the traditional parochial spaces of old sycophants and new enemies in Kenya. The writer also seems to have softened his stance on language possible from recognizing the complexities that plague a new Kenyan writing generation. At the Jalada event his position was that we need as many languages as possible even if one needs to understand his own mother tongue best.

Now with a steadily growing youth-based grassroots anger at the state and its perpetual failed promises, Ngugi and others are being vindicated in the eyes of a younger generation who are angry at their parents for a Kenya that has failed to live up to its earlier promise. The same generation that now attends Kamirithu Polytechnic and many others like it across the country. What Ngugi used to point out regularly with many others who were targeted by the state is now a common diet that characterizes popular political grassroots movements such as Bunge La Wananchi at the public Jeevanjee gardens who fight for lower prices of maize meal for their ugali.

We will yet again wait to hear the outcome of this year’s Nobel Prize. Two years ago bookmakers cast him as one of the favourites. I have no doubt that if he wins those old forces will start bubbling. Ngugi will have his Soyinka-Chineizu moment where a coterie of Kenyan-based academics and writers will scream murder. This seems to be the lot of the African writer. It is almost guaranteed that such an achievement, as Ngugi winning the Nobel would, like the Obama Presidency, be celebrated more in Kenya’s neighboring countries, which have a less complicated relationship with him. This is more than Binyavanga’s “Pull Him Down”; it is also what I call a realism neurosis to describe street reactions to contemporary African novels especially when internationally popular.

The wags will ask what practical use are such books compared say to a book on how to be financially successful. What is the importance of Ngugi’s early novels Weep Not Child and The River Between and their village settings when crime and corruption are our most visible social issues in Kenya today? If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a civilization to produce a writer of Ngugi’s stature. And yet in Kenya, I feel that we are yet to understand that. We are great because of Ngugi and other Kenyan writers of his generation and beyond. And so I remember what Ngugi said to us at that Kwani? Litfest years ago. If you are not proud enough to write in your language no one will be proud for you.