Lit Hub Staff Picks: Our Favorite Stories This Month

The Best Writing at the Site in January

From essays to interviews, excerpts and reading lists, we publish around 150 features a month. And though we’re proud of each week’s offerings, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of our favorite pieces of writing from the month at Lit Hub.

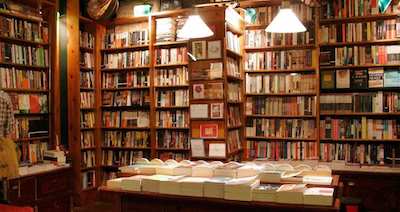

![]()

“On the Experience of Entering a Bookstore in Your Forties (vs. Your Twenties)” by Steve Edwards

“On the Experience of Entering a Bookstore in Your Forties (vs. Your Twenties)” by Steve Edwards

Being, at this moment, neither in my twenties nor my forties, but somewhere in between, I began reading this piece hoping for a little bit of fortune-telling. Instead, what I found was a lovely, moving essay about books and the way they attract us, shape us, and leave us—or not. “You can only read To the Lighthouse for the first time once before you’ll always know they never made it there,” Edwards writes, and I feel a little pang, because I have always been saddened by this very thing, and never before seen it written down anywhere. Which, I suppose, is often why we read at all.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

“Where New York’s Single Literary Girls Lived” by Amy Rowland

“Where New York’s Single Literary Girls Lived” by Amy Rowland

This piece combines so many things I love to read about: failure (honestly, if that reading about an instance of writerly failure doesn’t comfort you, I don’t trust you), terrible jobs, and weird living situations. Amy Rowland’s story of living in a women-only boardinghouse in the 90s (as a “retreat from the world” when no one wanted to publish her novel) is a funny and delightful depiction of a strange subculture as well as a humane account of that most human conditions, the downswing.

–Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub social media editor

“Why I Started Publishing an ‘Indigenous Version’ of My Articles” by Jenni Monet

“Why I Started Publishing an ‘Indigenous Version’ of My Articles” by Jenni Monet

“What stories and perspectives are missing in today’s newsfeeds?” If you’ve wondered this, you are not alone, and you should probably read award-winning journalist Jenni Monet’s personal essay in which she describes her experiences in colonized newsrooms and her decision to “sequester the editorial gap” by self-publishing her stories. From rejected edits to questionable photo choices, this piece will offer some insight into the editorial process and point you in the direction of some of Jenni Monet’s untouched work.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

“What Do I Risk Losing by Writing Down My Family’s Stories in English?” by Jamil Jan Kochai

“What Do I Risk Losing by Writing Down My Family’s Stories in English?” by Jamil Jan Kochai

Jamil Jan Kochai recounts his return to appreciation for the oral storytelling tradition of his Pakhto-speaking grandparents and grapples with everything he’s lost, first by ignoring these stories, and then by attempting to translate them into English and to write them down. In this article that is so painfully relatable for any child of immigrants, especially those with an interest in Words, Kochai argues for “rejecting the supremacy of the Text,” a return to his true job as a writer to serve stories and the Word.

–Kevin Chau, Lit Hub editorial fellow

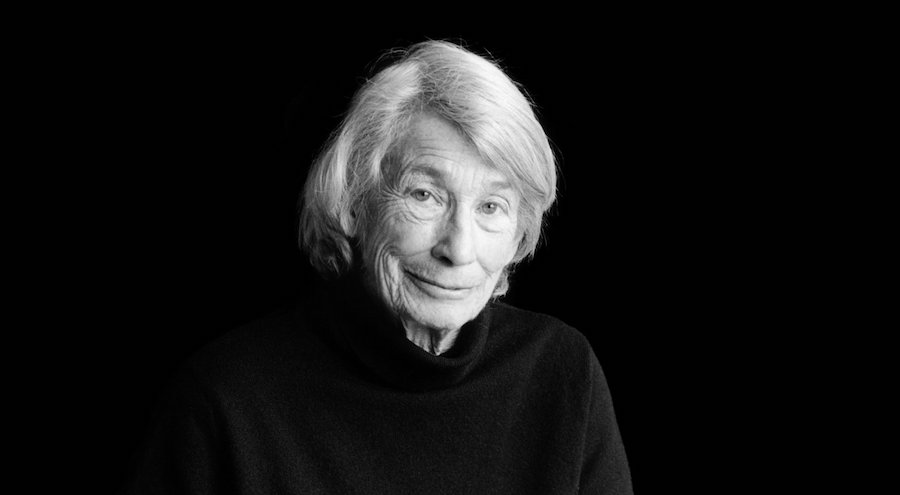

“On the Overlooked Eroticism of Mary Oliver” by Jeanna Kadlec

“On the Overlooked Eroticism of Mary Oliver” by Jeanna Kadlec

Among the many beautiful tributes to Mary Oliver that were published this month, one stands out to me: Jeanna Kadlec’s essay on the queer eroticism in her poetry, an often-overlooked aspect of her life and work. A famously private person, Oliver did not often talk about her personal life or her relationship with her longtime partner, Molly Malone Cook, and while her writing resonated with millions of people, this aspect of it has typically been left out of the public conversation. Kadlec considers the role of queer desire in Oliver’s poetry, starting with the often-quoted line, “You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.”

–Corinne Segal, Lit Hub senior editor

“On the Myth of an Edenic, Pre-Columbian ‘New’ World” by David Treuer

I’m cheating a bit here: this is actually an excerpt from David Treuer’s ambitious and important (yes, important! I am available for jacket copy), history of Indigenous life in North America from 1890 to the present, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee. What happened in 1890? The massacre of Wounded Knee, in which 300 Lakota men, women, and children were murdered by the United States Army, all of which (and much, much more) was immortalized in Dee Brown’s widely read 1970 history Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Foundational to Treuer’s project here is that Indian life is far too readily consigned to the language of elegy and tragedy, and that despite a dozen generations of colonizer predation there is yet richness, complexity, and joy among the living First Nations; that even as we lament the cruelties of the past we can celebrate the humanity of the present.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

“On The Casual Sociopathy of the Traditional Mystery,” by Gytha Lodge

“On The Casual Sociopathy of the Traditional Mystery,” by Gytha Lodge

“Was this really what happened in Agatha Christie? Surely she wasn’t quite so casual about death.” In this thoughtful take on the dark side of traditional and cozy mysteries, Gytha Lodge looks at the dangers of presenting murder as acceptable entertainment merely because the crime is not messy. By the logic of this article, the more violent and discomforting a death in a crime novel is, the less exploitative of human suffering it becomes. An unusual take on an oft-discussed topic!

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor

“When Even the Greatest of Writers Grapples With Self Doubt,” by Gabrielle Bellot

This meditative piece by Gabrielle Bellot on the last poems of W. B. Yeats—wherein he grappled with aging, self-doubt, and despair—is a beautiful, lyrical reminder for writers everywhere not to give up, even when it seems that the well of creativity has run dry and inspiration will never strike again. “With or without fame, we can never know if our work will live on,” Bellot writes. “Perhaps it’s enough to sing, and keep singing, and hope, after our own night-shawl has closed around us, that someone else will hear it, and, hardest of all, remember it.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks senior editor

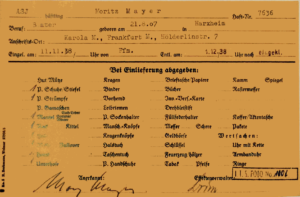

“My Name is Fritz Mayer: An Account of Buchenwald” by Mark Mayer

“My Name is Fritz Mayer: An Account of Buchenwald” by Mark Mayer

In this short piece which we published on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Mark Mayer explains that his grandfather’s story of survival is much more complex and lucky than the stranger-than-fiction “story of two Fritz Mayers” relayed here. But it is a story about being alive, the terror of dying, and brings to life a history that can never be forgotten.

–Emily Firetog, Lit Hub deputy editor

“How A British Bookseller Fell in Love With American Noir” by Joseph Knox

“How A British Bookseller Fell in Love With American Noir” by Joseph Knox

“They took everything they had, their words, their tragedies, their disappointments, and weaponized them into pin-prick sharp novels of enduring power, wit and insight.” Crime writer Joseph Knox discovered the joys of American noir as a British bookseller steeped in a searingly personal and funny, often dark, distinctly stylish genre—much of which was unpublished at the time in the UK. For those looking for an entree into crime fiction, this ode to American noir adoringly mentions some of the all-time greats, and is likely to turn the last crime holdouts into converts.

–Camille LeBlanc, CrimeReads editorial fellow

“Into a Crueler America: Two Border Crossings, 30 Years Apart” by Reyna Grande

“Into a Crueler America: Two Border Crossings, 30 Years Apart” by Reyna Grande

While on the road promoting her memoir about her family’s own immigration story, Reyna Grande sees a man on her plane with nothing but the clothes on his back. It turns out he’s just been released from a detention center, hungry and confused. How easy it is for to help him, Grande realizes, once they begin speaking, to treat him with respect, to appreciate the luxury of her own position. Grande doesn’t for a second aggrandize herself by describing this awakening. Instead, she had written a little model for how to live in these cruel times. Kindness, she shows, isn’t just necessary, it’s far easier than we think to live by, especially if we pay attention to what’s around us.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

“The Virtue of Giddiness in Art” by Rosie Haward

“The Virtue of Giddiness in Art” by Rosie Haward

After reading Rosie Haward’s thrilling, sensual dive into the meaning of “giddiness,” I started doubting whether I’d ever properly experienced the feeling. In writing about the representation of women in a Gian Lorenzo Bernini sculpture (The Ecstasy of St. Teresa) and two films (Ecstasy, 1933 & Possession, 1981), Haward gives due to “bodies that are both fluid and static but also always ecstatic in their giddiness.” It’s a lyrical romp disguised as media criticism—a formalistic collapse that hints at the apparent queerness of “fixed” forms.

–Aaron Robertson, Lit Hub assistant editor