Seventy-five years ago, in February 1945, some of the last battles of World War II were still being fought but the Allies—US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin—knew the defeat of Nazi Germany was not far off. Their next great challenge was to decide how to manage the peace and to do that the three leaders needed to meet face to face, as they had last done in Teheran in 1943. Under pressure from Stalin, the chosen venue was on his home territory—the Black Sea resort of Yalta on the Crimean Peninsula, recently liberated from the Nazis.

Between February 4 and 11, 1945 the “Big Three”—as the press called them—made decisions that resonate to this day. Stalin’s price for Soviet entry into the war against Japan enabled the Red Army to advance into Korea and precipitated the Korean War, leading to the continuing partition of Korea and the ongoing confrontation with the Kim dynasty today. Yalta also seeded the ground for the Cold War. Within just weeks Stalin violated protocols signed at the conference that should have guaranteed democratic freedoms for the countries of Eastern Europe, and the Iron Curtain began to descend.

This diary reveals—often in the words of those who were there—what happened on each of eight momentous days, exactly 75 years ago, as Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill not only defined a new world order but bequeathed a problematic legacy to our time. Head here to read days one, two, and three.

*

Day Four

Wednesday, February 7, “brilliant sunshine”

Morning: Livadia Palace

American delegates are tiring of the lavish food. Harry Hopkins’s son Robert, attending as a US army photographer, complains, about the “abundance of beluga caviar at the Livadia Palace … a heaping saucer of caviar for each person is the first course at breakfast every day followed by herring, bread, fruit and tea. The menu never varies.” General Marshall, who detests fish and is allergic to shellfish, is struggling with the Black Sea turbot, bass, shrimp, squid, and crayfish so often on the menu, and relying on the stack of jumbo-size Hershey bars he has brought with him.

10.00: Livadia Palace

US Chiefs of Staff endorse the bomb line separating those areas which the British and American air forces will attack from those the rapidly advancing Soviets will assault. It runs through Berlin, Dresden and Vienna to Zagreb.

15.00: En route to Livadia Palace

Sarah Churchill accompanies her father on the drive to the Livadia for the day’s plenary session. The sun is shining “so hard on the sea” that the reflection makes them blink. “The Riviera of Hades,” Churchill says.

16.00: Grand Ballroom, Livadia Palace

The fourth plenary session opens and Roosevelt raises Poland. They must act boldly and decisively to agree a provisional government: “We want something new and drastic—like a breath of fresh air.” Stalin claims he only received the President’s letter “an hour and a half ago.” He has tried but failed to reach the leaders of the Lublin Poles. As for the other Poles suggested by Roosevelt, he doubts “they could be located in time to come to the Crimea.” However, his Foreign Minister Molotov has proposals “which appear to approach the President’s suggestions” but they are being translated into English. While they wait, Stalin suggests they discuss the United Nations.

Molotov reports that, having considered the US proposals, “the Soviet Government feels that these fully guarantee the unity of the Great Powers in the matter of preservation of peace” and are “entirely acceptable.” Soviet official Ian Maisky notes the palpable relief of the American and British delegations with “smiles on many lips.” However, Molotov has a sting in the tail. He asks for three of the sixteen Soviet Republics to be admitted to the General Assembly of the United Nations—Ukraine, Belorussia and Lithuania—“the first to be invaded by the enemy.” Surely they deserve membership as much as British Dominions like Australia and Canada, Molotov says. Having told Congress he will oppose extra seats for the Soviet Union, Roosevelt is in a quandary. He suggests referring the issue to Foreign Ministers but has reckoned without Churchill.

“It would be a great pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food it dies of indigestion.”Conscious of the implications of “one nation, one vote,” for his beloved British Empire, Churchill defends the right of Britain’s self-governing Dominions to seats in the UN General Assembly. By analogy he has “great sympathy” with the Soviet Union’s aspirations to have more than one voice. He will telegraph his War Cabinet tonight to ask their views. Knowing Churchill’s determination to protect Britain’s Dominions and even “to get India into the United Nations,” Roosevelt is neither surprised nor pleased.

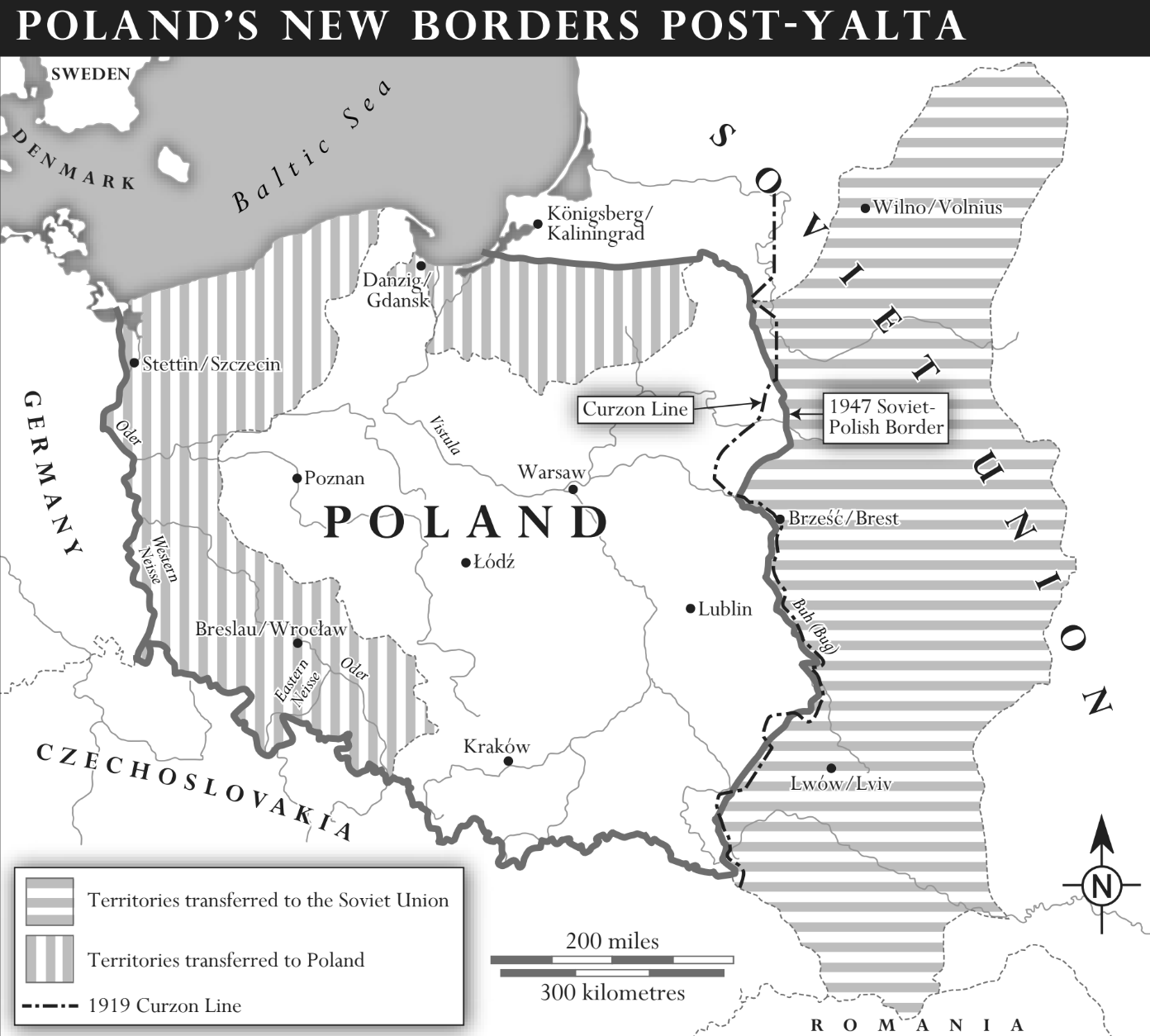

Translations of the Soviet proposals on Poland are handed out. On Poland’s eastern border, the Soviet Union will agree minor digressions in Poland’s favor. The western border should be the Oder and Western Neisse Rivers. On Poland’s future government, the Soviets suggest “some democratic leaders from Polish émigré circles” be added to the Lublin group. After the Allies recognize this enlarged government, it would hold elections “as soon as possible.” Molotov repeats Stalin’s claim that it has been impossible to contact anyone in Poland but insists the Soviet proposals “go far toward meeting the President’s wishes.”

Neither Roosevelt nor Churchill challenge the ridiculous fiction that the Soviets cannot contact either the Lublin Poles or others. Neither do they challenge the fact that these proposals assume the retention of the Soviet-backed Lublin group as the core of the provisional government, rather than the establishment of an entirely new body as they have asked. They request more time to study the proposals.

On Poland’s borders, Churchill says he has always favored a westward shift but not more than the Poles can handle: “It would be a great pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food it dies of indigestion.” Also, the British public would be “frankly shocked” at the forcible transportation westward of so many millions of Germans. Stalin suggests quietly that this is not a problem since “most Germans in those areas have already run away from the Red Army.” Churchill acknowledges this makes matters easier: “Moreover, 6 or 7 million Germans have already been killed, and at least 1 or 1.5 million more will probably be killed before the end of the war,” which will create more space. Nevertheless, the transfer of such huge numbers of people must be considered in the context of “the capacity of the Poles to handle it and the capability of the Germans to receive them.” He will “sleep on this problem.”

20.00: The session adjourns.

That evening: Vorontsov Palace

Churchill telegraphs his War Cabinet in London that “Today has been much better. All the American proposals for the United Nations constitution were accepted by the Russians.” Britain is asking “a great deal” in having places in the General Assembly for her Dominions as well as herself. It would shield Britain from criticism if two or three Soviet republics had seats. Furthermore, a friendly gesture to the Soviets might be expedient to secure concessions on Poland for which he perceives a glimmer of hope.

Churchill provides his cabinet colleagues with a little vignette of Yalta: “In spite of our gloomy warnings and forebodings, Yalta has turned out very well so far. It is a sheltered strip of austere Riviera, with winding Corniche roads. The villas and palaces … are of an extinct imperialism and nobility. In these we squat on furniture carried with extraordinary effort from Moscow.”

That evening: Roosevelt’s apartments, Livadia Palace

The President debates with his advisors what to do about the Soviet request for extra seats in the UN General Assembly. “From the standpoint of geography and population,” he realizes, there is nothing preposterous about the proposal, especially as real power will rest in the Security Council. Should he make such a concession? He is undecided.

Late night: Yusupov Palace

Around midnight, Stalin and his military commanders sit down to eat. The key topic of conversation is the Soviet Union’s price for joining the war against Japan.

CHECK BACK TOMORROW FOR A DIARY OF DAY FIVE.

_______________________________________

Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World, by Diana Preston is available now from Grove Atlantic. Featured image: meeting of Foreign Ministers in the Yusupov Palace prior to the 4th plenary session. (Molotov is third from the left; UK Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden is across the table next the man with glasses; Stettinius is third from the right, with Harriman to his right.)