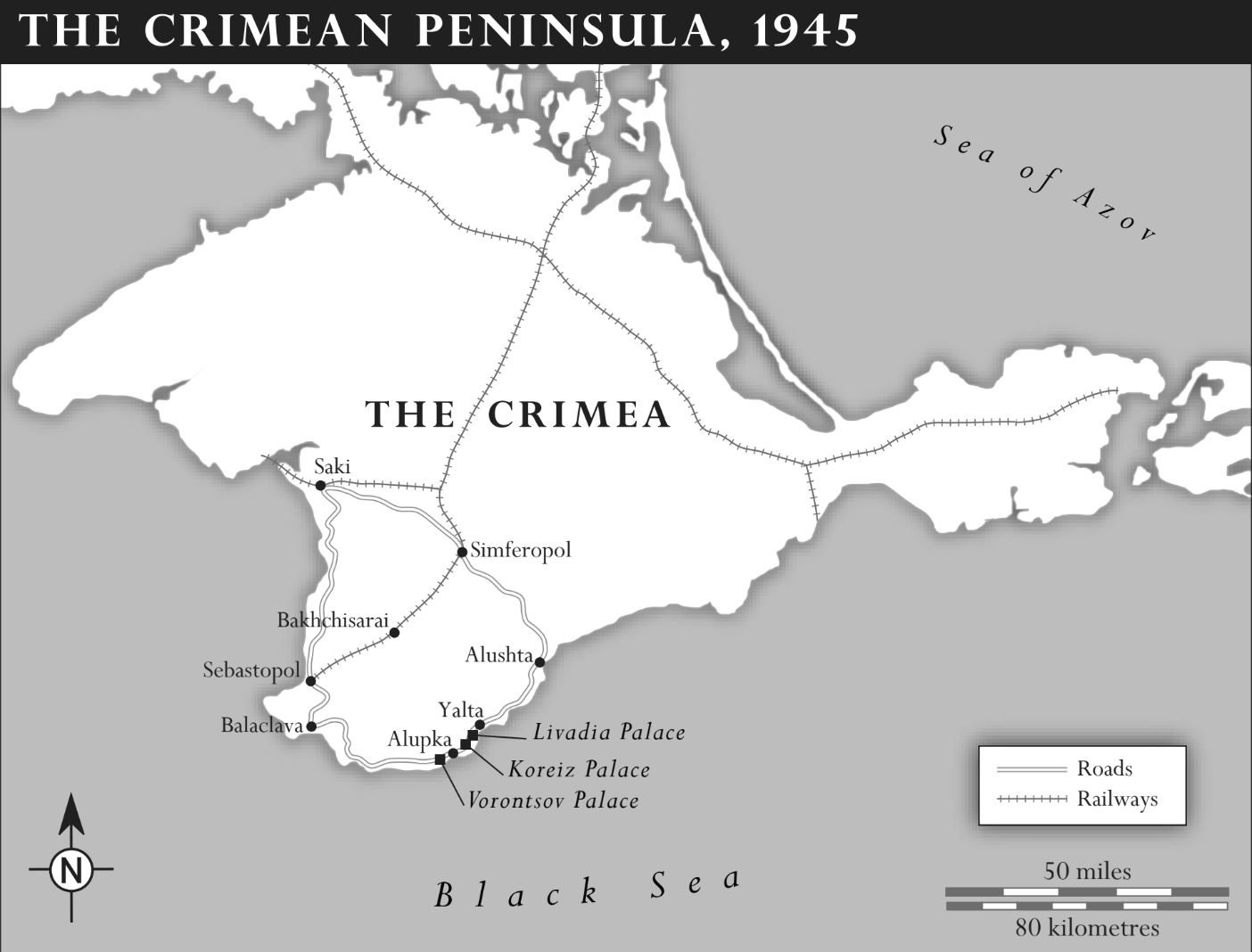

Seventy-five years ago, in February 1945, some of the last battles of World War II were still being fought but the Allies—US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin—knew the defeat of Nazi Germany was not far off. Their next great challenge was to decide how to manage the peace and to do that the three leaders needed to meet face to face, as they had last done in Teheran in 1943. Under pressure from Stalin, the chosen venue was on his home territory—the Black Sea resort of Yalta on the Crimean Peninsula, recently liberated from the Nazis.

The frail Roosevelt, who had only weeks to live and whose entourage included his daughter Anna Boettiger, left Washington in the Ferdinand Magellan presidential railcar to begin his taxing journey a third of the way around the world. In war-blitzed London, Churchill and his daughter Sarah boarded a plane for a cold flight on the first leg of their journey, while Stalin left Moscow in a heavily armored train that carried him south across snowy, shattered landscapes still strewn with burned-out tanks.

Safely arrived in the Crimea, the leaders and their teams settled into three hastily renovated palaces outside Yalta: Stalin and his team in the hilltop Yusupov Palace that had once belonged to Rasputin’s assassin, Prince Felix Yusupov; the US delegation in the Italianate white marble Livadia Palace constructed by the last czar, in whose Grand Ballroom the conference’s plenary sessions would convene where grand duchesses once waltzed; the UK delegation in the Vorontsov Palace, a fantastical structure described by Churchill’s daughter Sarah as “a Scottish baronial hall inside and a Swiss Chalet plus Mosque outside!” Both the Vorontsov and Livadia palaces had—as the Americans and British guessed—been extensively bugged by Stalin’s security chief Lavrentii Beria so he could eavesdrop on their conversations. Inside the palaces, an army of staff from Moscow’s top hotels prepared to wait on the visitors. Outside, machine gun-toting members of Beria’s notorious security force, the NKVD, patrolled the grounds.

As they prepared to meet, the only objective the three leaders shared completely was the swift defeat of Nazi Germany. Otherwise each had his own agenda, his own priorities. Stalin wanted a swift end to the war, massive reparations from a defeated Germany and the establishment of a buffer zone of compliant states around the Soviet Union. Roosevelt hoped to agree to terms with Stalin for the Soviet Union’s swift entry into the war against Japan, and thus to save a million young American lives likely to be lost in an invasion of the Japanese home islands, to win Stalin’s approval for his plans for a United Nations organization, and to secure a democratic future for recently liberated countries. Churchill wanted to preserve a war-weakened Britain’s dwindling influence in the world, to safeguard its empire, and to ensure fair and free government in Eastern Europe, especially Poland, for whom in 1939 Britain had gone to war.

Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill not only defined a new world order but bequeathed a problematic legacy to our time.Between February 4 and 11, 1945 the “Big Three”—as the press called them—made decisions that resonate to this day. Stalin’s price for Soviet entry into the war against Japan enabled the Red Army to advance into Korea and precipitated the Korean War, leading to the continuing partition of Korea and the ongoing confrontation with the Kim dynasty today. Yalta also seeded the ground for the Cold War. Within just weeks Stalin violated protocols signed at the conference that should have guaranteed democratic freedoms for the countries of Eastern Europe, and the Iron Curtain began to descend.

The new United Nations organization set up at Yalta should have been able to intervene, but the voting arrangements agreed there allowed the Soviet Union, as one of the five permanent members of the Security Council possessing a veto, to prevent action. With the UN hamstrung ever since by these voting rules, the world continues to struggle over how to contain Russian territorial ambitions such as their recent occupation of the Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine, just as Roosevelt and Churchill battled in vain for the freedom of Eastern Europe, much of it already occupied by Soviet troops.

The decision of the “Big Three” to exclude the haughty Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle from Yalta also had far-reaching consequences. It fueled de Gaulle’s suspicion that the UK and US planned an Anglo-American hegemony and, in the 1960s, was a factor in his decision twice to veto Britain’s entry into the European Community. Arguably, had Britain entered earlier, it might have had greater influence, integrated better, and Brexit might not have happened.

This diary reveals—often in the words of those who were there—what happened on each of eight momentous days, exactly 75 years ago, as Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill not only defined a new world order but bequeathed a problematic legacy to our time.

*

Day One

Sunday, February 4, 1945, a “wonderfully mild” day in Yalta

10:30: Livadia Palace

With the conference about to begin, President Roosevelt confers with his senior advisers including silver-haired Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, US ambassador to Moscow Averell Harriman, and military chiefs Admiral William Leahy, General George Marshall, Admiral Ernest King, and General Laurence Kuter about US priorities. Harriman says Stalin will “very likely wish to raise the question of what the Russians would get” in return for entering the war against Japan.

President Roosevelt meets with his advisors in the Livadia Palace. Left to right: Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Major General L.S. Kuter, Admiral E.J. King, General George C. Marshall, Ambassador to the Soviet Union Averill Harriman, Admiral William Leahy, Roosevelt. Photo: United States Army Signal Corps.

President Roosevelt meets with his advisors in the Livadia Palace. Left to right: Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Major General L.S. Kuter, Admiral E.J. King, General George C. Marshall, Ambassador to the Soviet Union Averill Harriman, Admiral William Leahy, Roosevelt. Photo: United States Army Signal Corps.

Noon: Yusupov Palace

British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden’s car negotiates the precarious road winding high above the Black Sea to the Yusupov for him to call on Vyacheslav Molotov, his Soviet counterpart, in hopes of deciding common objectives for the conference. He and Molotov—known as “Stone Arse” for his ability to sit for hours in negotiations saying “no”—agree that the current military situation in Europe and the treatment of Nazi Germany, once defeated, should top the agenda. They should also discuss Roosevelt’s brainchild, the new United Nations organization. However, when Eden proposes the conference should consider the future of Poland, Molotov snaps that Poland, now occupied by the Red Army, must be left to manage its own affairs.

Early afternoon: Vorontsov Palace

Stalin arrives in his black heavily armored Packard limousine for private talks with Churchill. He exults over “the helpless situation in which the German army is now placed in Poland and East Prussia.” When Churchill asks what Stalin would do if Hitler fled Berlin, Stalin assures him “the Soviet armies will hunt him down.”

16.15: Roosevelt’s private apartments, Livadia Palace

Stalin arrives for a private meeting with Roosevelt watched by Stettinius who thinks “his powerful head and shoulders set on a stocky body” radiate “great strength.” Mixing a pitcher of dry martinis, Roosevelt passes a glass to Stalin, apologizing that “a good martini should really have a twist of lemon.” Next day, a huge lemon tree flown in from Stalin’s native Georgia and bowing under the weight of 200 pieces of fruit will appear in the Livadia’s entrance hall. Roosevelt tells Stalin the devastation he has seen in the Crimea has made him “more bloodthirsty in regard to the Germans than a year ago.” Stalin warns that much hard fighting remains to defeat the German “savages.” He presses for a swift, emphatic US/UK advance across the Rhine into the Ruhr to precipitate Germany’s economic collapse.

Joseph Stalin in Moscow, August 1945. To his immediate left: Georgy Malenkov, Lavrentii Beria, and Vyacheslav Molotov. To his immediate right is his eventual successor, Nikita Khruschev. Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd.

Joseph Stalin in Moscow, August 1945. To his immediate left: Georgy Malenkov, Lavrentii Beria, and Vyacheslav Molotov. To his immediate right is his eventual successor, Nikita Khruschev. Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd.

Roosevelt and Stalin discuss the Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle who, by the unanimous and instant consent of the three leaders, has not been invited to Yalta and who, Roosevelt remarks, likens himself to Joan of Arc. Stalin dismisses de Gaulle as a “very complicated” man whose expectations that his country be treated equally with the Soviet Union, US and UK are unrealistic since in 1940 “France had not fought at all.” He asks whether they should give France a zone of occupation in a defeated Germany. “Only out of kindness,” the President replies.

Finally, Roosevelt, keen to conciliate Stalin by distancing himself from Churchill, tells Stalin “something indiscreet” he wouldn’t wish to say “in front of Prime Minister Churchill”—that the British want France built up into a military power strong enough to hold the line for a while if another European war occurs. The British are “a peculiar people” who want “to have their cake and eat it too,” expecting the Americans to “restore order in France,” then hand political control to them.

17.00: Grand Ballroom, Livadia Palace

US, British, and Soviet still photographers and motion-picture cameramen jostle to capture the delegates’ arrival for the first plenary session. An aide pushes Roosevelt into the ballroom in his wheelchair. Churchill arrives in a colonel’s uniform. The Soviet delegation, led by Stalin, enters last. When all are seated at the large round table near a crackling birchwood fire, Stalin invites Roosevelt, as the only head of state present, to open the conference. Roosevelt pauses for dramatic effect. When he speaks, he predicts the conference “will cover the map of the world” but proposes they first discuss the latest military position. Harriman thinks Stalin feels “a certain awe” of the president and “is afraid of Roosevelt’s influence in the world.”

General Antonov, head of the Soviet military delegation, describes how since January 12 Soviet troops have advanced 300 miles and are over the River Oder within 50 miles of Berlin. They have destroyed 45 German divisions and taken 100,000 prisoners but suffered 300,000 casualties. He asks the American and British to accelerate their armies’ advance and to launch air strikes against rail junctions in Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig to hinder German troop movements eastwards, to which the US and British delegations readily agree. General Marshall reports that in the west American and British fighter aircraft and light bombers have already destroyed “a great deal of German transport” and oil supplies but that German forces are continuing to bombard the key port of Antwerp with “robot bombs and rockets” (V2s, the world’s first ballistic missile).

He warns that ice floes churning in the swift current of the Rhine will prevent any attempt to cross before March 1 and that the German navy “are about to resume large-scale submarine warfare” using their new schnorkel vessels, whose ventilation tubes enable them to remain submerged for extended periods, making them hard to detect and destroy. Using forceful language and rising from his chair and “emphasizing his points with dramatic gestures,” Stalin queries the number of US and UK tanks and divisions, pointing out that in recent fighting the Russians deployed 9,000 tanks. Churchill reassures him about the US and UK’s overwhelming advantage over German forces in aircraft and armor, though not infantry. When Stalin asks what more the western Allies want Soviet forces to do, Churchill says only to continue “to do as they are doing now” and proposes that next day they discuss “the future of Germany, if she has any.” Stalin and Roosevelt agree.

19.50

The first plenary session adjourns

20.30: Livadia Palace

Roosevelt hosts a small formal dinner for Stalin and Churchill at which his Filipino mess crew from Shangri La [Camp David] serve a Russo-American fusion of caviar, sturgeon, chicken salad, meat-pie and Southern-style fried chicken. Guests drink Russian champagne and vodka, five types of wine and make dozens of toasts. Stalin waters his vodka and during the meal tries out English expressions—“What the hell goes on around here?” and “You said it!”—that he has learned watching American films. However, he looks offended when Roosevelt confides how he and Churchill call him “Uncle Joe” as a term of endearment and the mood changes. Discussion turns to preserving the coming peace. Churchill says the great powers must respect the right of smaller nations, but Stalin insists only those who have borne the brunt of the fighting can have a say in determining the peace.

Midnight: Vorontsov Palace

Anthony Eden writes in his diary “Stalin’s attitude to small countries struck me as grim, not to say sinister.”

CHECK BACK TOMORROW FOR A DIARY OF DAY TWO.

_______________________________________

Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World, by Diana Preston is available now from Grove Atlantic.