20 Notoriously Underrated Writers You Should Be Reading

Yes, Even Nobel Prize-Winners Can Be Chronically Underappreciated

What makes an author underrated? Well, there’s an argument to be made that most literary writers are—by virtue of the fact that these days they are sorely under-read by the culture at large. But even within the sphere of the literary community, some great writers get forgotten or ignored, and others are simply not appreciated as much as they should be. So for our purposes here, “underrated” will mean both “rated below their value” and “not rated enough.” It does not, as you will see, necessarily mean unknown!

Of course, rating of any kind is subjective (don’t tell Book Marks), and to that end, rather than subject you to my own scattered notions, I have instead collated the opinions of other reputable sources—critics, writers, and journalists who have, at one time or another, deemed an an author underrated, underappreciated, or otherwise unfairly ignored. That doesn’t exactly solve the opinion problem, but I’ve tried for the most part to include only those authors who are often considered to be deserving of a wider audience. Twenty of these are noted below, but the list, as ever, could go on and on. Who would you add?

Robert Walser

Robert Walser

According to Benjamin Weissman, writing in the LA Times:

Robert Walser (1878-1956) is the dreamy confectionary snowflake of German language fiction. He also might be the single most underrated writer of the 20th century. Even though his prose is quite delicious—and no matter how many times his perfect novel, Jakob Von Gunten, is reissued—booksellers rarely stock him. Walser is a sentence artist of the highest magnitude who spent his last 27 years in an asylum in Switzerland.

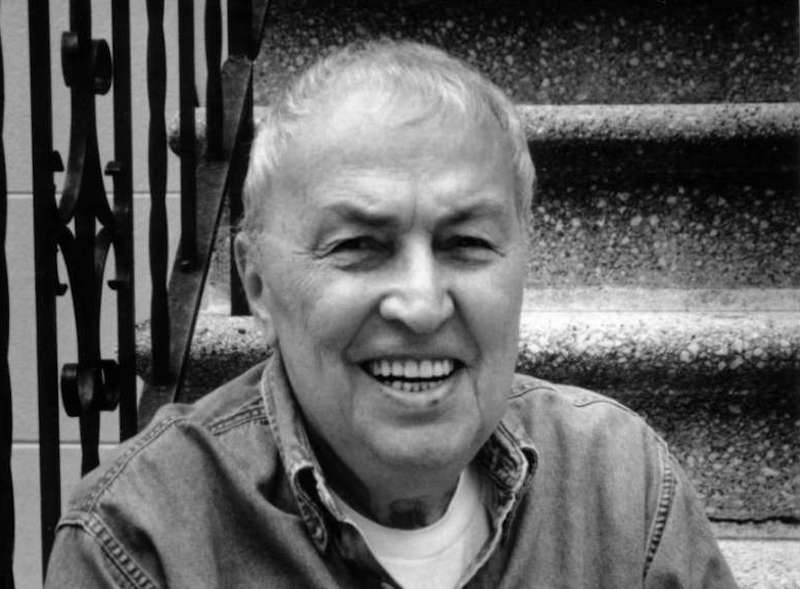

James Salter

James Salter

According to Alex Bilmes, writing in Esquire:

Slowly, his literary stock has risen, but he has not yet achieved wide recognition or sales commensurate with his status among other writers. His work has been saluted by a parade of literary giants (Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, Philip Roth, John Irving), and he has won prestigious awards and the favour of influential critics (Susan Sontag, Harold Bloom), but just as often Salter has been dismissed by the press and overlooked by the academy, and almost consistently he has been ignored by the public.

Partly for those reasons he is a romantic figure, almost a mythic figure, especially to other writers. But his cult status is not simply derived from his relative lack of commercial success. It is also the result of his subtle, supple and seductive voice on the page.

Also famously described by James Wolcott in Vanity Fair as America’s most “underrated underrated author.”

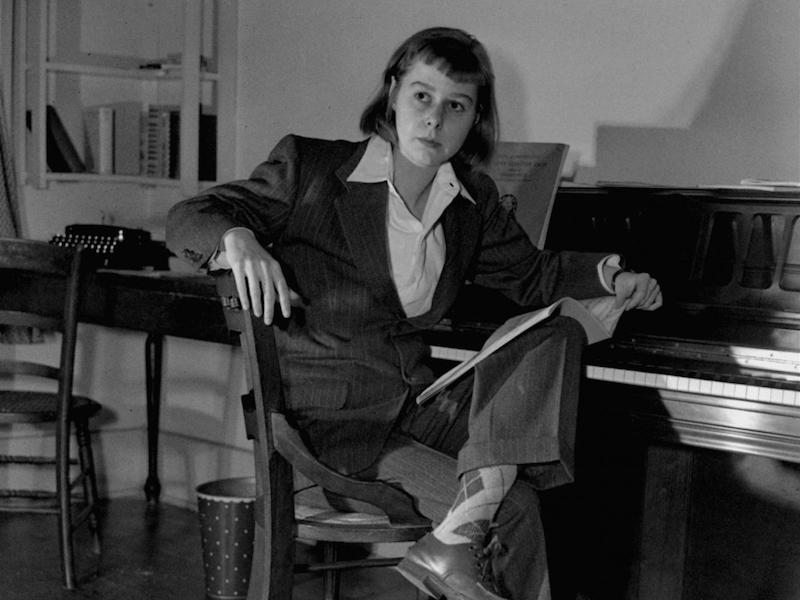

Carson McCullers

Carson McCullers

According to Sarah Schulman, writing in Literary Hub:

Absolutely our most underrated writer, McCullers has been relegated to the “southern gothic” ghetto. But she had the immense power of transcendence and was able to represent all kinds of people far outside of her personal experience. From the gay, Jewish deaf mute of Heart is a Lonely Hunter, to the magnetic dwarf of Sad Cafe, her work is a singular lesson in human identification. Richard Wright, the author of Black Boy, reviewed her first novel, published in 1940 at the age of 22, and said she was the first white writer to create fully human black characters. Sad Cafe features the single most specific and explosive definition I have ever read of the difference between loving and being loved.

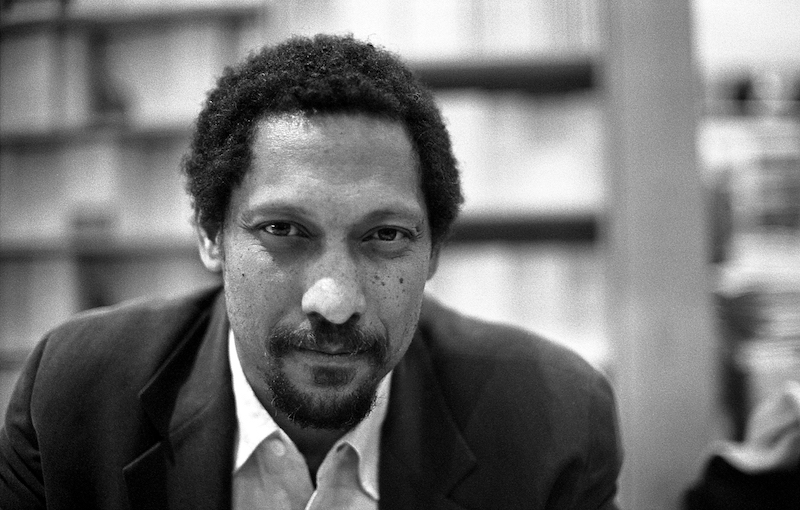

Percival Everett

Percival Everett

According to Michael Schaub, writing for NPR:

It’s not surprising that So Much Blue is such a perfectly structured novel; Everett is an author who started his career off strong and just keeps getting better. It’s a generous, thrilling book by a man who might well be America’s most under-recognized literary master, and readers will be thinking about it long after the last page. As Kevin observes at one point: “Like most things that come back to haunt you, it haunted me in the beginning. No ghost is born overnight.”

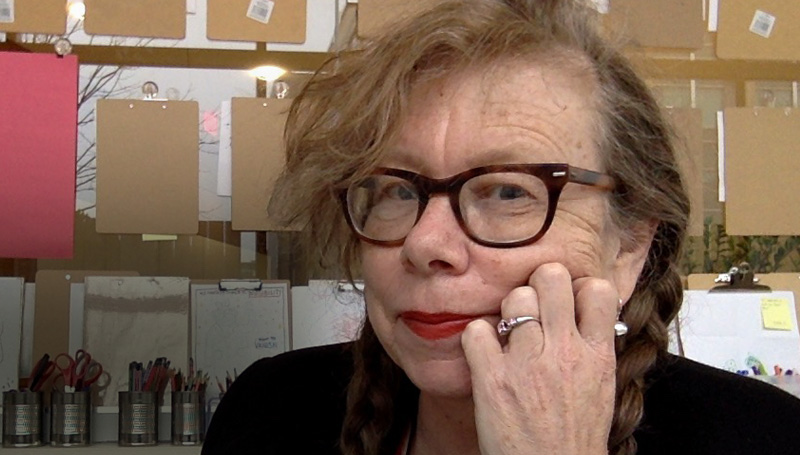

Lynda Barry

Lynda Barry

According to Mary-Louise Parker, writing for Oprah:

Lynda Barry might be the most underrated writer ever. She is the wisest and funniest chronicler of adolescence in America, and when my inner loner starts wailing uncontrollably, I pick up anything of hers and laugh until my face hurts, until she inevitably hits me with something so profoundly true and heartbreaking, I wonder if she’s been spying on me my whole life.

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym

Famously nominated as “the most underrated writer of the 20th century” by Philip Larkin in a 1977 TLS survey—which also relaunched her career.

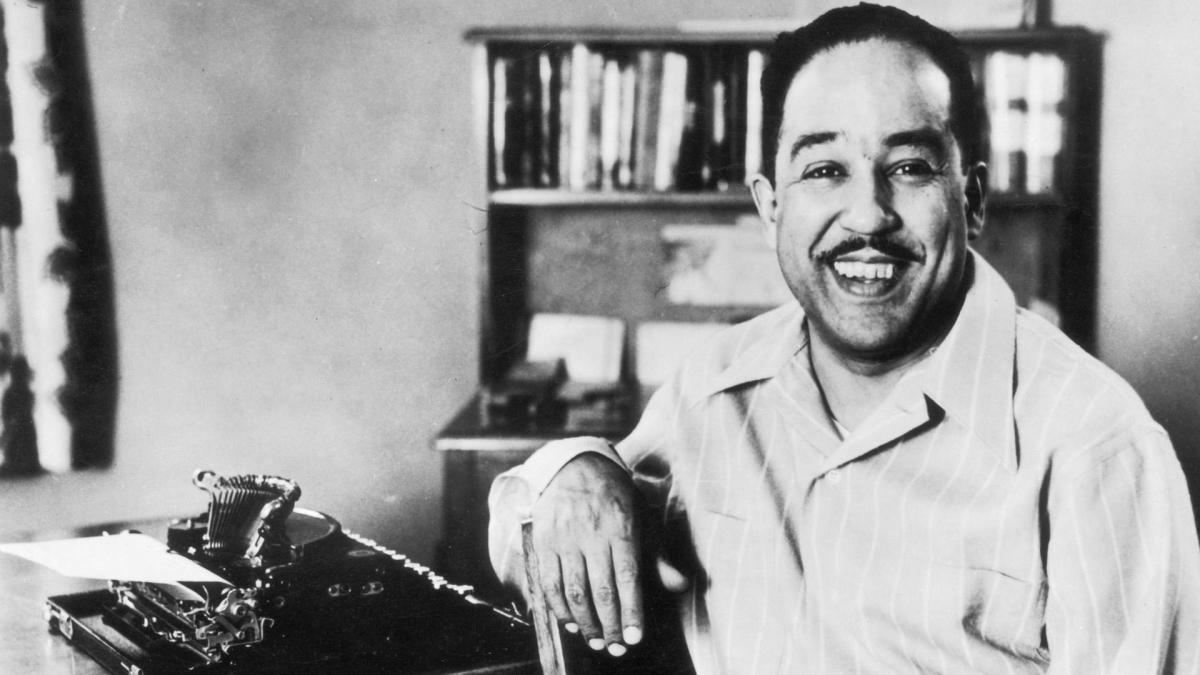

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes

According to Amiri Baraka, in his 1986 introduction to The Big Sea:

Langston Hughes is, in one sense, the most underrated writer in this country. His name is conjured recently, with encouraging frequency, yet there are a startling majority of American artists who know even less than cocktail party jabber about the Black masses’ main poetic man.

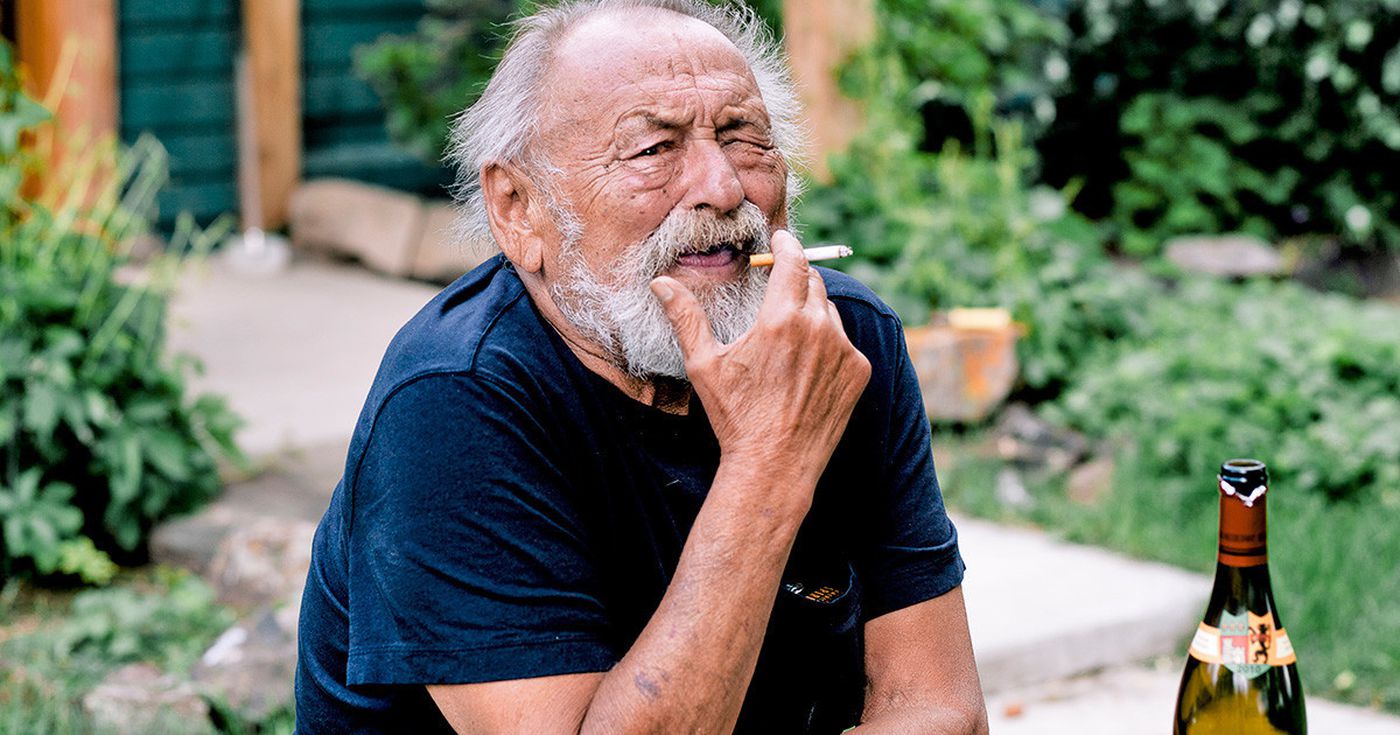

Jim Harrison

Jim Harrison

According to Bill Morris, writing for The Daily Beast:

A friend and I were talking the other day when the conversation ran up against a maddening mystery: How is it possible that a smallish army of discerning readers agree that Jim Harrison is one of the few truly great living American writers, yet he has not gotten the wider audience—or the widespread praise—he so plainly deserves?

The question is especially timely because Harrison has just come out with a new novel, The Big Seven, which reprises his “retired careworn cop,” Simon Sunderson, who just wants to go trout fishing in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula but runs into a clan of inbred homicidal hellions. It’s Harrison’s 36th book, which means that his impossibly varied yet impossibly consistent output—novels, novellas, short stories, poems, reportage, memoir, and some wicked writing about food—now occupies roughly one yard of shelf space. Why isn’t this man regarded as a national treasure?

Edward St. Aubyn

Edward St. Aubyn

According to Lev Grossman, writing in TIME:

The second book I want to talk about is Edward St. Aubyn’s At Last. I wrote once in this space that I thought St. Aubyn (you say it Saint Aw-bin) might be the most underrated novelist writing in English. Generally when I go for the big statement like that, I wince when I think about it later. But I’m still not wincing. When I read St. Aubyn I’m floored over and over again by the warmth and intelligence and eloquence of his work, the moreso because he traverses landscapes of such extreme emotional bleakness.

. . .

I read the grandly comprehensive, massively praised social novels of English writers like Alan Hollinghurst and Philip Hensher, and I absolutely appreciate their grandeur and their comprehensiveness; but I learned more about humanity from At Last than I did from those books, and had a better time doing it, too. After years of being under-published in the U.S., St. Aubyn has been taken up by Farrar, Straus Giroux, which is bringing out At Last with great fanfare; Picador is also reissuing the first four books in one volume. With any luck St. Aubyn will finally get his due. Then I can nominate somebody else for most-underrated novelist in English instead.

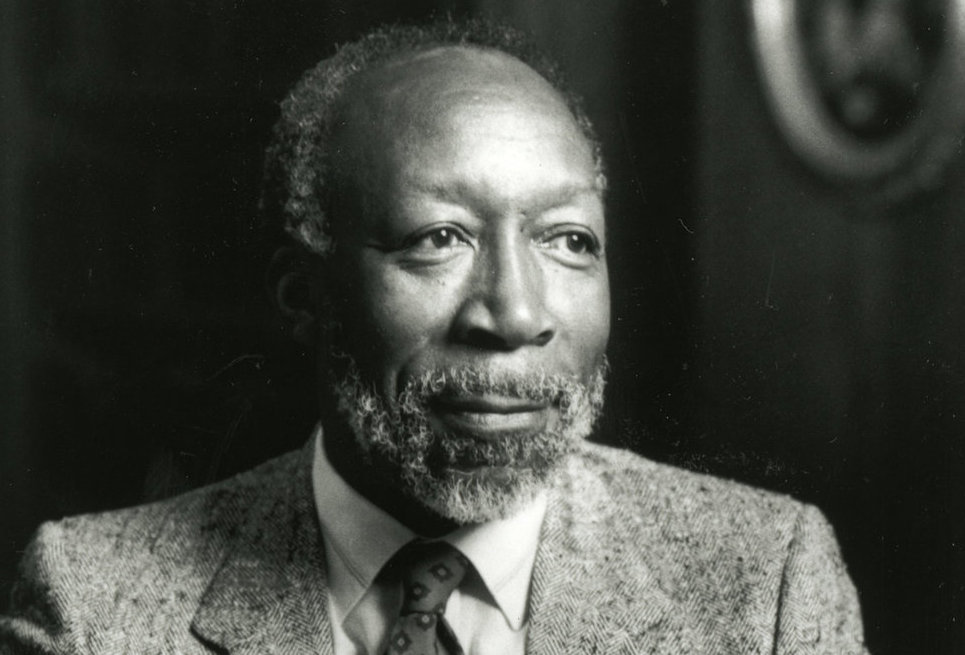

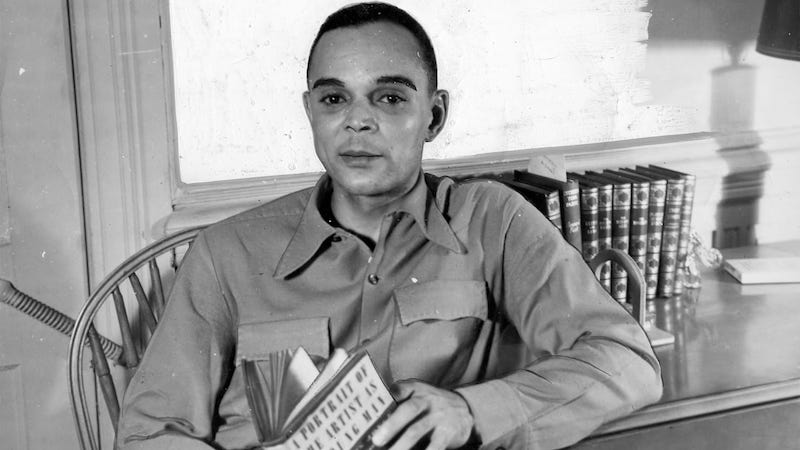

John A. Williams

John A. Williams

According to Williams’ obituary in the New York Times:

Mr. Williams, whom the critic James L. de Jongh called “arguably the finest Afro-American novelist of his generation,” excelled in describing the inner lives of characters struggling to make sense of their experiences, their personal relationships and their place in a hostile society. His manifest gifts, however, earned him at best a twilight kind of fame — a reputation for being chronically underrated.

Night Song, his second novel, published in 1961, caught the attention of critics with its compelling picture of the jazz world of Greenwich Village and the retrospective ruminations of its hero, a dying saxophonist. “He gets close enough to the good novel about jazz that has never yet been written to make one hope he may write a good novel about something,” the British magazine The Spectator said in its review.

That novel was “The Man Who Cried I Am, a look at 30 years of American history through the eyes of a dying black American writer living in Europe who reflects on his life and on his troubled marriage to a Dutch woman. Eliot Fremont-Smith, in his review for The New York Times, called it “a compelling novel, gracefully written, angry but acute, committed but controlled, obviously timely, but deserving of attention for far more than that.”

John Williams

John Williams

According to Tim Kreider, writing in The New Yorker:

In one of those few gratifying instances of belated artistic justice, John Williams’s Stoner has become an unexpected bestseller in Europe after being translated and championed by the French writer Anna Gavalda. Once every decade or so, someone like me tries to do the same service for it in the U.S., writing an essay arguing that Stoner is a great, chronically underappreciated American novel. (The latest of these, which also lists several previous such essays, is Morris Dickstein’s for the Times.) And yet it goes on being largely undiscovered in its own country, passed around and praised only among a bookish cognoscenti, and its author, John Williams, consigned to that unenviable category inhabited by such august company as Richard Yates and James Salter: the writer’s writer.

(Though at this point we should note that Stoner has become famous for not being famous enough, whatever that means.)

Alice Munro

Alice Munro

According to Jonathan Franzen, writing in The New York Times (though before her Nobel Prize. . . ):

Alice Munro has a strong claim to being the best fiction writer now working in North America, but outside of Canada, where her books are No. 1 best sellers, she has never had a large readership. At the risk of sounding like a pleader on behalf of yet another underappreciated writer—and maybe you’ve learned to recognize and evade these pleas? The same way you’ve learned not to open bulk mail from certain charities? Please give generously to Dawn Powell? Your contribution of just 15 minutes a week can help assure Joseph Roth of his rightful place in the modern canon?—I want to circle around Munro’s latest marvel of a book, “Runaway,” by taking some guesses at why her excellence so dismayingly exceeds her fame.

. . .

But who is Alice Munro? She is the remote provider of intensely pleasurable private experiences. And since I’m not interested in reviewing her new book’s marketing campaign or in being entertainingly snarky at her expense, and since I’m reluctant to talk about the concrete meaning of her new work, because this is difficult to do without revealing too much plot, I’m probably better off just serving up a nice quote for Alfred A. Knopf to pull—”Munro has a strong claim to being the best fiction writer now working in North America. ‘Runaway’ is a marvel”—and suggesting to the Book Review’s editors that they run the biggest possible photograph of Munro in the most prominent of places, plus a few smaller photos of mildly prurient interest (her kitchen? her children?) and maybe a quote from one of her rare interviews—”Because there is this kind of exhaustion and bewilderment when you look at your work. . . . All you really have left is the thing you’re working on now. And so you’re much more thinly clothed. You’re like somebody out in a little shirt or something, which is just the work you’re doing now and the strange identification with everything you’ve done before. And this probably is why I don’t take any public role as a writer. Because I can’t see myself doing that except as a gigantic fraud”—and just leave it at that.

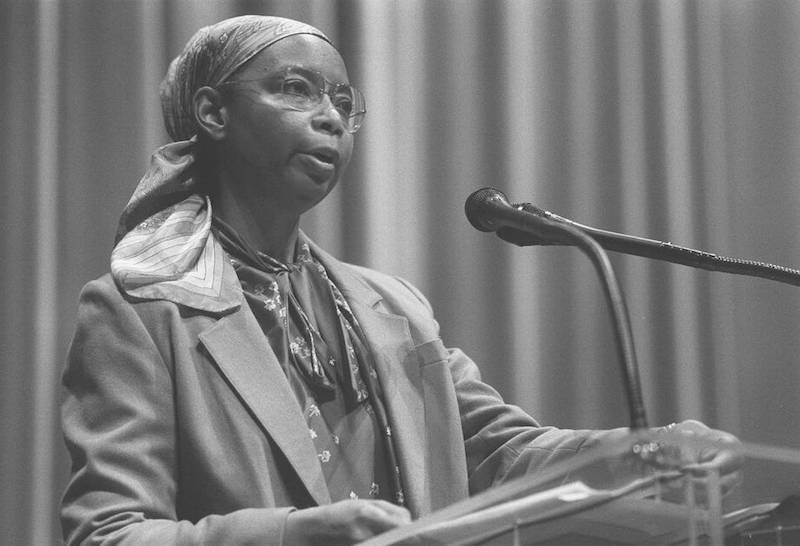

Gayl Jones

Gayl Jones

According to Daniel Handler, interviewed by the TLS:

For the life of me I cannot see why Gayl Jones is not considered a major American writer. Her eye is fierce and wise, her prose is vivid and gorgeous and her subject matter is a necessary addition to the conversation.

Christina Stead

Christina Stead

According to Jonathan Franzen, writing in The New York Times:

Anyone trying to revive interest in [The Man Who Loved Children] at this late date will labor under the shadow of the poet Randall Jarrell’s long and dazzling introduction to its 1965 reissue. Not only can nobody praise the book more roundly and minutely than Jarrell already did, but if an appeal as powerful as his couldn’t turn the world on to the book, back in the day when our country still took literature halfway seriously, it seems highly unlikely that anybody else can now. Indeed, one very good reason to read the novel is that you can then read Jarrell’s introduction and be reminded of what outstanding literary criticism used to look like: passionate, personal, fair-minded, thorough and intended for ordinary readers. If you still care about fiction, it might make you nostalgic.

Jarrell, who repeatedly linked Stead with Tolstoy, was clearly taking his best shot at installing her in the Western canon, and in this he clearly failed. A 1980 study of the 100 most-cited literary writers of the 20th century, based on scholarly citations from the late 1970s, found Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein and Anaïs Nin on the list, but not Christina Stead. This would be less puzzling if Stead and her best novel didn’t positively cry out for academic criticism of every stripe. Especially confounding is that The Man Who Loved Children has failed to become a core text in every women’s studies program in the country.

David Markson

David Markson

According to his obituary in The New York Times:

David Markson, whose wry, elliptical novels probing the scattered mind of the artist and the unruly craft of making art were frequently called postmodern and experimental and almost always surprisingly engaging and underappreciated, died Friday in his Greenwich Village apartment.

. . .

Though his books—including Springer’s Progress (1977), Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988) and This Is Not a Novel (2001)—were often admiringly reviewed, Mr. Markson was a novelist well known largely to other novelists. This was partly because he was a central figure in the Village writing scene in the 1960s, a frequenter of literary watering holes like the Lion’s Head, but also because he eschewed conventional novelistic forms and tropes. Like other experimentalists, he made the form of the novel, at least in part, its subject.

Ellie Partovi

Ellie Partovi

Dana Johnson

According to Roxane Gay, interviewed in the TLS:

Dana Johnson is really underrated. Since I read her first book, Break Any Woman Down, I’ve been absolutely intrigued by her writing. She has a strong sense of style, pacing and narrative voice. And she is consistently excellent.

Adam Thorpe

Adam Thorpe

According to Eileen Battersby, writing in Irish Times:

It is a familiar theme; a person vanishes and life goes on, as it does with relentless indifference. Many novelists have been drawn to disappearances, often within a political context. This time it is somehow different. But then poet Adam Thorpe, author of nine previous novels and two short story collections, is not only Britain’s most underrated writer, he is also among the most original.

And according to Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

Thorpe’s career is surely one of the great literary mysteries of the age. In the years since Ulverton, he has published a further nine novels; Flight, a thriller about a messed-up freight pilot, came out earlier this year. They are inevitably superb—my favourite is Between Each Breath, an extraordinarily clever and beautifully written tale of music, marriage and Estonia—and always well-reviewed, and yet you look for his name in vain on Booker and bestseller lists alike. To me, this is as baffling as it is unfair, and I wonder how he accounts for it. “I don’t know,” he says, quietly. “One can hardly say I’ve been unambitious.”

Marcel Schwob

Marcel Schwob

According to Stephen Sparks in Literary Hub:

Marcel Schwob may be the most influential writer you’ve never heard of. Criminally overlooked in the English-speaking world, Schwob—a sort of French Robert Louis Stevenson—nevertheless exerted influence over a diverse array of his more famous successors, including Alfred Jarry, Borges, Paul Valery, Roberto Bolaño, and others. He is the epitome of the writer no one thinks they read, but who, due to his profound influence, lives on in the work of others.

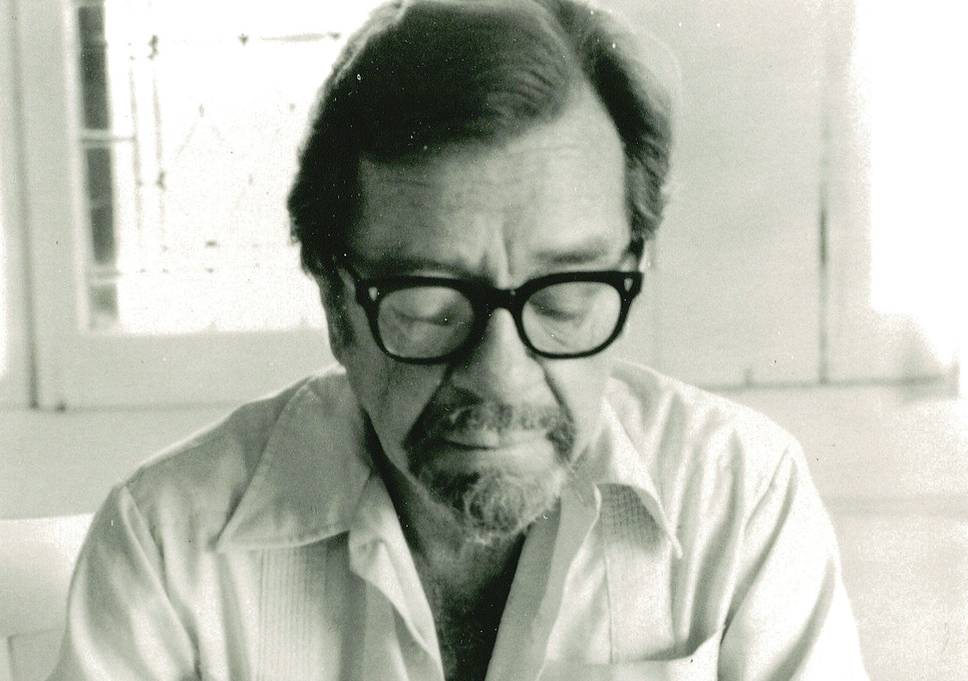

Chester Himes

Chester Himes

According to Luc Sante in The New York Review of Books:

After his complex realist novels of race relations were met with indifference and scorn in America, he moved to France. There, his obscurity seemed total until a publisher of detective paperbacks persuaded him to attempt a crime novel set in Harlem, a milieu he, as a Midwesterner, knew only glancingly. This first effort was striking and original, and it was a roaring success in French translation. Soon he found himself famous in Europe, although inconsistently solvent. His novels did not really make him much money until two of them were used as bases for Hollywood movies, by which time he had ceased to write them. Even the success of the movies failed to make the books catch on in the United States and, by the time Himes died, all of his work was out of print in English. It is only now, seven years after his death, that a majority of his books are again available in America, and then only after having been reprinted in England, so that some of the present American editions sport British spellings and vocabulary. Thus Himes, an important and singular African American writer, remains even posthumously an exile.

His biographer, James Sallis, described him as “one of America’s most neglected and misunderstood major writers.”

Henry Green

Henry Green

According to Leo Robson in The New Yorker:

His stock was high among fellow-writers. In a 1952 Life profile, W. H. Auden was quoted calling him “the best English novelist alive.” The following year, T. S. Eliot, talking to the Times, cited Green’s novels as proof that the “creative advance in our age is in prose fiction.” But Green had never been a popular success. In 1930, Evelyn Waugh had reviewed “Living,” Green’s novel about Birmingham factory life, under the headline “A Neglected Masterpiece.” It was the first of several dozen articles that bemoaned Green’s lack of acceptance and helped bind his name as closely to the epithet “neglected” as Pallas Athena is to “bright-eyed.”

Waugh blamed philistine book reviewers, but he knew that Green’s image hadn’t helped. “From motives inscrutable to his friends, the author of Livingchooses to publish his work under a pseudonym of peculiar drabness,” he wrote. . . . After a certain point, he refused to have his portrait taken. Dundy had first recognized him from a Cecil Beaton photograph that showed only the back of his head.

And according to David Lodge in The New York Review of Books:

Henry Green occupies a special but somewhat puzzling place in the history of modern English fiction. That his real name was Henry Yorke is symbolic of the general elusiveness of his literary identity. He seems to stand to one side of his fictional oeuvre, smiling enigmatically and challenging us to put a label, and a value, on it. He has been called a “writer’s writer,” and even, according to Terry Southern, “a writer’s-writer’s writer.” W. H. Auden, Eudora Welty, V. S. Pritchett, Rebecca West, and John Updike have all described him, at various times, and in various ways, as the finest novelist of his generation, yet he never enjoyed either the commercial success or the literary fame of contemporaries such as Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and Christopher Isherwood.

He was neither shrewd nor lucky in the development of his literary career. After a precocious and promising debut, Blindness (1926), begun while he was still at school, he wrote a brilliant novel about working-class life, Living (1929), several years before such subject matter became fashionable, and then took ten years to write his next, Party Going (1939)—a work whose concern with a group of narcissistic socialites setting off on a Continental holiday seemed rather frivolous in the encroaching shadows of World War II. In the 1940s he became more productive, and more widely read (Loving [1945] even appeared briefly on the US best-seller lists), but just as he was beginning to attract serious critical attention, interest was diverted by a new wave of British writers, the so-called Angry Young Men, with whose coarse, iconoclastic energies he had little affinity. Whether by coincidence or cause and effect, his creativity seemed to suddenly dry up at this time. The latter part of his life, from the publication of his last novel, Doting, in 1952, to his death in 1973, was a sad story of increasing reclusiveness, alcoholism, and melancholia. His novels went out of print, and his name virtually disappeared from the canon of modern British fiction.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.