Notable Literary Deaths in 2017

A Last Goodbye to the Authors and Editors We Lost This Year

This has not been the best year. In addition to, well everything, we lost a number of literary luminaries in 2017: beloved novelists, champions of the written word, legendary editors, and genre-defining journalists. Of course, as readers, we have not lost their work, which will last as long as any of the rest of us do (though I suppose we’ll have to see how long that is), and so we can remain grateful. Here, we pay tribute to some of those great writers, who will not be forgotten.

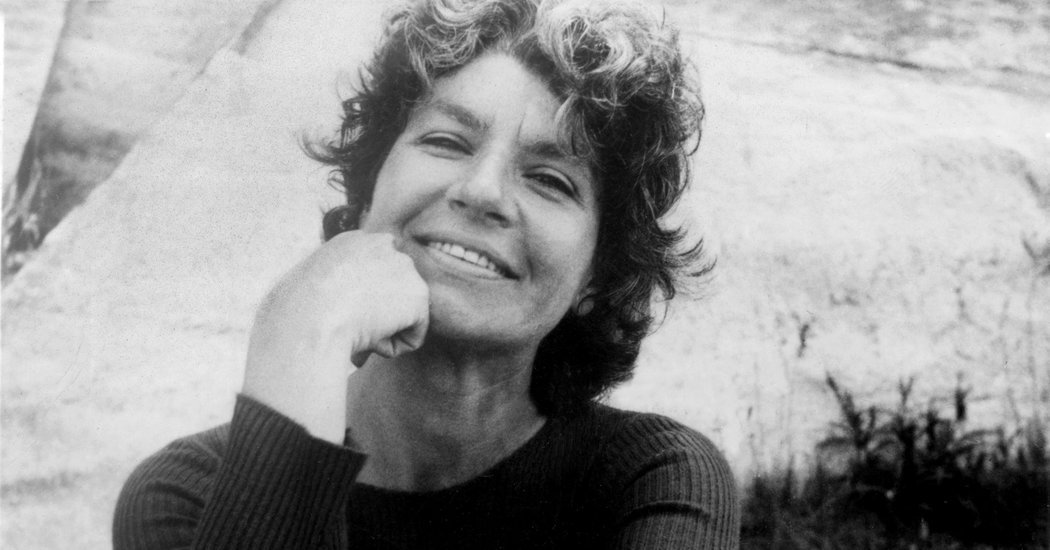

Paula Fox, March 1st

The prolific novelist, memoirist, and children’s book author Paula Fox died on March 1st in Brooklyn at the age of 93. She is perhaps best remembered for her excellent, barbed masterpiece Desperate Characters, which Tom Bissell called “a novel that cuts across generations and aesthetic tastes like no other modern novel I know. Postmodernists love it. I love it. Hipsters love it. Academics love it. Realists love it. My mother loves it.” That’s perhaps not so surprising for a novel about New York, and marriage, and rabies.

Derek Walcott, March 17th

Nobel Prize-winning poet and playwright Derek Walcott died on March 17th at the age of 87. Born in St. Lucia, Walcott was deeply invested in the notions of belonging and identity, and was also the recipient of MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, a Royal Society of Literature Award, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry, the inaugural OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, the T. S. Eliot Prize, and the Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award. “He captured the day-to-day and the epic alike,” Gabrielle Bellot wrote in a lovely remembrance of Walcott. “[His language] could be lazy and lacertilian, rhythmic as the tide, dense as our mountains and fleeting as their ghosts. You can hear T.S. Eliot through Walcott; more intriguingly still, you can read Eliot anew after Walcott. Frequently, he connected the Caribbean to the mythos of ancient Greece—most clearly in his own epic, Omeros, but ever-present elsewhere.” He was also filled with writing wisdom.

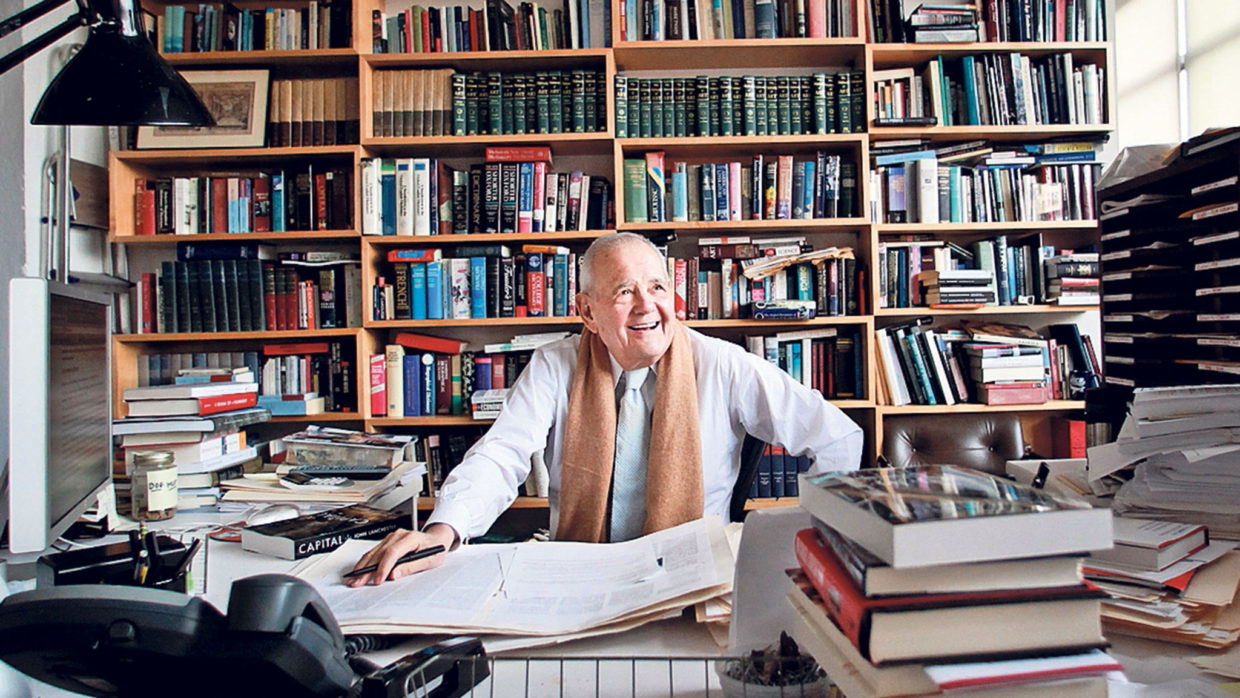

Robert B. Silvers, March 20th

Robert B. Silvers, founding editor of The New York Review of Books, devoted champion of writers, and instrumental force in the literary world, died in March the age of 87. “It’s just that he’s a marvelous, wonderful editor,” Joan Didion once said of Silvers. “It’s a responsiveness that you don’t usually find. Everyone who works with him marvels at it, I think.” He worked with Didion, not to mention Gore Vidal, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Susan Sontag. He mentored A.O. Scott, Deborah Eisenberg, and Darryl Pinckney. A once in a generation mind is gone, but at least we had him for as long as we did.

Robert M. Pirsig, April 24th

In April, Robert M. Pirsig, author of the cult novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, died at his home in South Berwick, Maine, at the age of 88. Pirsig was also a philosopher, and his famous novel introduces readers to his theory of the Metaphysics of Quality, which is not exactly Zen, but not wholly dissimilar to it. “Like a mother hiding spinach in the lasagna to get her kids to eat their veggies, Pirsig lures readers into exploring philosophical or intellectual terrain within a tale of day-to-day life,” Bernadette Murphy wrote. “In Z.M.M., the reader is drawn in by the narrator’s 17-day cross-country motorcycle trek and his relationship with his 11-year old son, Christopher. That human connection is what makes his flights into the theoretical realm not only palatable but organically necessary.” For his part, Pirsig said: “I think metaphysics is good if it improves everyday life; otherwise forget it.”

Jean Stein, April 30th

Jean Stein, who honed the art of the oral history to perfection with her biographies of Robert Kennedy and Edie Sedgwick, both co-authored by George Plimpton, died in April at the age of 83. She worked at The Paris Review and Esquire, and was the editor and publisher of Grand Street from 1990 to 2004. Her most recent book was West of Eden, an oral history of Los Angeles that became a bestseller. Before her death, she established the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award and the PEN/Jean Stein Grant for Oral History, the former of which “focuses global attention on remarkable books that propel experimentation, wit, strength, and the expression of wisdom.” She is also well remembered for her epic parties.

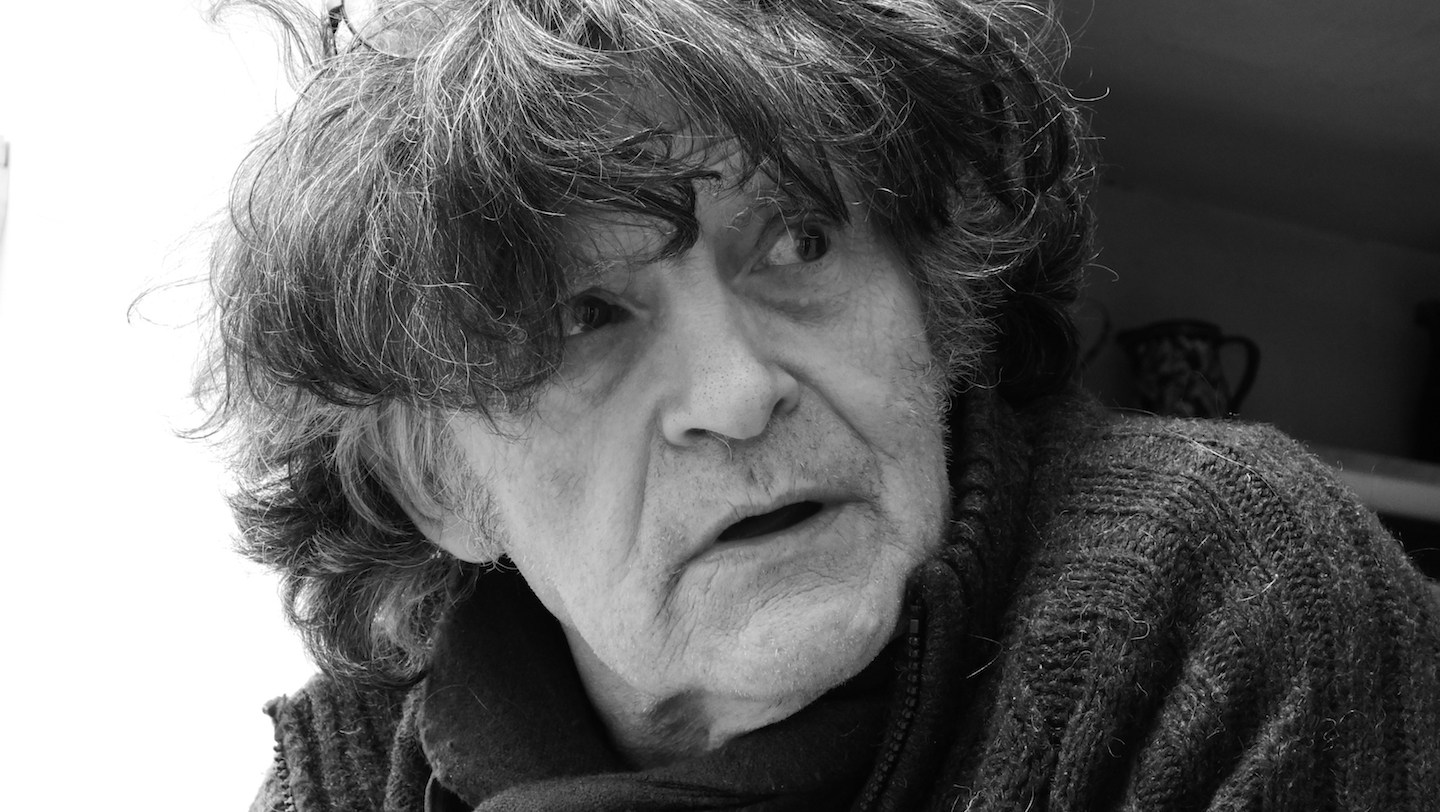

Denis Johnson, May 24th

Influential novelist and short story writer Denis Johnson died in May at the age of 67. His collection Jesus’ Son is a touchstone for many, many writers, the kind of book that has gets passed hand to hand, with whispers and knowing looks. He’s the rare cult author that has also enjoyed mainstream success: he has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Whiting Award; in 2007, he won the National Book Award for Tree of Smoke, and in 2012 was a Pulitzer finalist for Train Dreams. His death sent shockwaves through the literary world. “Denis spent his life writing about our better angels, in about as oblique, and earned, a way as anyone could imagine,” Jim Shepard told us. “He was our master of rendering moments of psychological nakedness so palpable that the comic and the piteous, the appalling and the transcendent, were made to lie down together. He never ceased to remind us that somewhere inside that self that we presented to the world—that self that we knew so often disheartened others—there was that person we wished the world could know; that person we wished that we ourselves could more consistently glimpse.”

Michael Bond, June 27th

Michael Bond, creator of Paddington Bear, died in June at his home in London at the age of 91. The character surprised even Bond by becoming a worldwide sensation, selling 35 million copies of the books, which have been translated into 40 languages. “I am constantly surprised by all the translations,” Bond once said, “because I thought that Paddington was essentially an English character.” After Bond’s death, author Francesca Simon said that he “created that infinitely rare thing: an iconic, utterly original, instantly recognisable and memorable character. He was one of the greats.”

Heathcote Williams, July 1st

The radical poet Heathcote Williams, who as The New York Times put it, was also a “playwright, actor, lyricist, painter, sculptor, magician and relentless scourge of the British establishment for half a century,” died of lung disease in July at the age of 75. “If you were to take the exploding typewriter of William Burroughs, add a soupçon of sophistication from Marshall McLuhan, a little popular science, a few comic books and a dash of popular psychology, and then stew the whole thing up with hate, then I suppose you might come out with a play such as Heathcote Williams’s AC/DC, Clive Barnes wrote in a 1970 review of Williams’s play. Williams was not only compared to Burroughs in his time, but also Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Blake, D.H. Lawrence, and other writers in the “great tradition of visionary dissent.” He also spray-painted graffiti on Buckingham Palace, which takes some guts.

Photo: Liu Xia

Photo: Liu Xia

Liu Xiaobo, July 13th

Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese essayist and poet, who was found guilty of “inciting subversion of state power” based on his criticism (literary and otherwise) of the Chinese government, and awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while imprisoned, died in July of liver cancer while under guard in a hospital, at the age of 61. “Liu Xiaobo will remain a powerful symbol for all who fight for freedom, democracy and a better world,” Berit Reiss-Andersen, the chairwoman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, told The New York Times. “He was truly a prisoner of conscience, and he paid the highest possible price for his relentless struggle.”

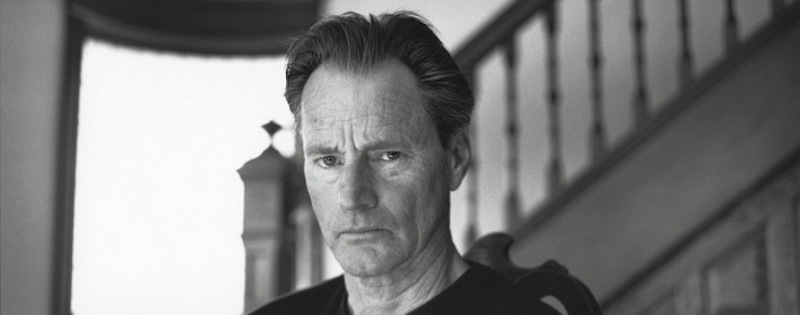

Sam Shepard, July 27th

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, actor, and American icon Sam Shepard died at home in July at the age of 73, from complications from Lou Gehrig’s disease. His work was often bleak, infused with black humor, beautiful glimpses at the fringes of life in America. In Shepard’s plays, Ben Brantley wrote in The New York Times, “he dismantled the classic iconography of cowboys and homesteaders, of American dreams and white picket fences, and reworked the landscape of deserts and farmlands into his own shimmering expanse of surreal estate. In Mr. Shepard’s plays, the only undeniable truth is that of the mirage. . . he presented a world in which nothing is fixed.” He was prolific, avant-garde, and served as a rallying voice for many self-described outsiders. “I’ve heard writers talk about ‘discovering a voice,’ but for me that wasn’t a problem,” he told The Paris Review. “There were so many voices that I didn’t know where to start. It was splendid, really; I felt kind of like a weird stenographer.”

Judith Jones, August 2nd

Judith Jones, the editor responsible for bringing us The Diary of Anne Frank (which she rescued from a pile of rejects when she was an editorial assistant, arguing it into existence) and who discovered Julia Child, died in August at the age of 93. She worked at Knopf from 1957 to 2011, when she retired as a senior editor and vice president. Jones was also a cookbook author and memoirist in her own right, and in 2006 was awarded a James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award.

Lillian Ross, September 20th

Legendary journalist Lillian Ross—who worked at The New Yorker for seven decades, to the tune of more than five hundred articles—died in September at the age of 99. “Ms. Ross’s particular skill was to charm her subjects into revealing their most unscripted, id-like selves, as Hemingway memorably did during a three-day tour of New York City with Ms. Ross at his side,” Penelope Green wrote in The New York Times. “In the article that resulted, a riveting, hilarious work of cinematic journalism, she nailed, among other quirks, Hemingway’s idiosyncratic, article-free “Indian talk:” “Book is like engine,” Hemingway told her. “We have to slack her off gradually.” With that piece, “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?” Ms. Ross largely invented the modern entertainment profile; it would also earn her accusations that the work was a vicious parody, though Hemingway had read it before publication and adored it.”

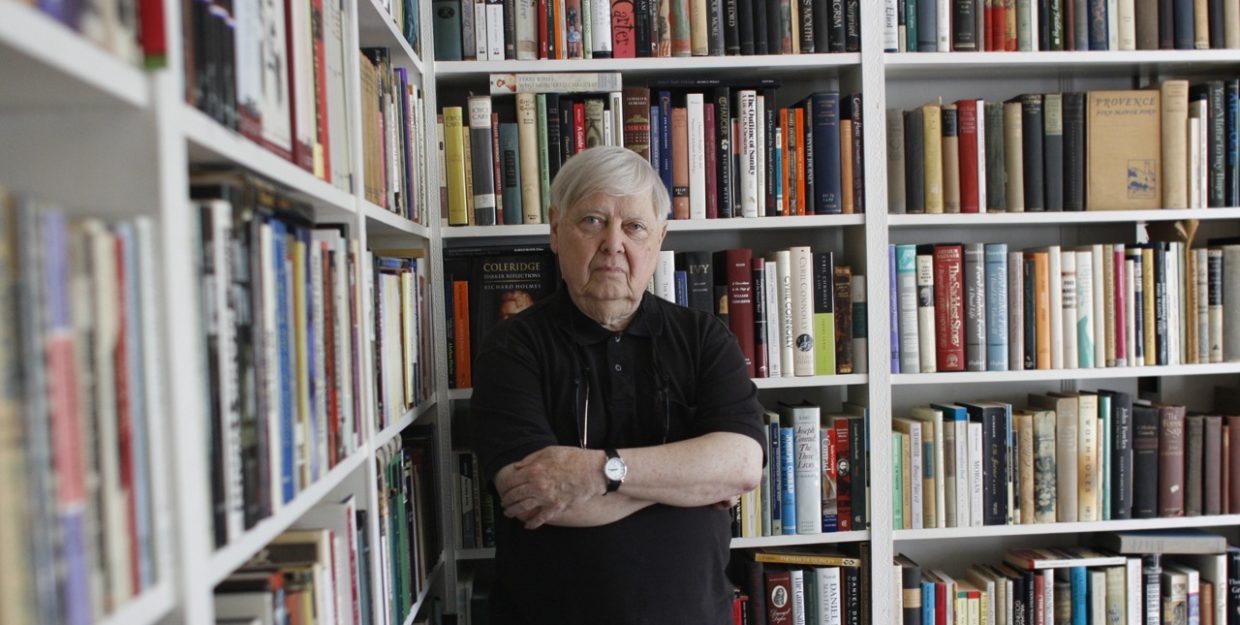

William H. Gass, December 6th

Boundary-breaking experimental writer, essayist, critic and philosophy professor William H. Gass died this month at the age of 93 at his home in St. Louis. He will be remembered, first and foremost, as one of our best masters of the sentence. “It was Gass’s strangeness, structured in precise language and uncanny metaphor, that made me return to his work,” Nick Ripatrazone wrote. “The cold incantations of “The Pedersen Kid” were mimetic and metafictive in the same moment; certainly Gass was some kind of magician? A philosopher who could make me feel?” Yes, I’d say.

Bette Howland, December 13th

Writer, critic, and MacArthur “Genius” grant recipient Bette Howland died last week at the age of 80. “No matter what her subject is, Mrs. Howland is always looking for the bone and marrow of Chicago,” Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote in a 1978 review of Blue in Chicago. “And always the prose with which she searches is arrhythmical, nervous, self-questioning, passionate. You can’t fall into step with her, because the moment you do she shifts her cadence and takes off for another part of town, another time, another thing about Chicago.” However, though much awarded and clearly brilliant, she has in recent years been more-or-less forgotten by the literary establishment. “What happened to a career that held such talent and promise?” A.N. Devers asked in a 2015 piece about Howland and her rediscovery by Brigid Hughes, Howland was nomadic and often lived in isolation. Why did she retreat from what she had earned for herself? What role has the literary community played in allowing her work to fall from memory? Her son Jacob thinks the MacArthur is part of the answer.” Indeed, she didn’t publish anything else after winning the award.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.