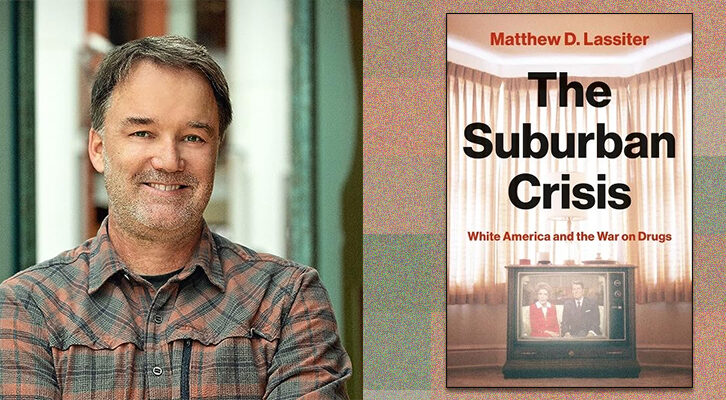

Why I Had to Leave Home to Write About It

Tyler Barton on the Path to Developing a Story

Once at a party, I was introduced as a writer. It felt kind of nice for a second. But then a stranger who had gone to my high school asked me what it was I wrote about. I’ll never forget the way this simple question made me stumble. “I don’t know… uh—normal people?”

“Oh! I’ve seen that book at Target.”

“No, that’s Sally Rooney.”

“I meant like, who’s your audience?” he asked, smirking, crushing me. This party took place in York County, Pennsylvania, hosted by my oldest friends in a dilapidated house they all shared. I’d just graduated from an MFA, and I couldn’t answer.

Flustered, I said something about Art. I may have been drunk. My face certainly flushed. Why was I suddenly peeved? And at whom? My buddies still get belly-laughs from reminding me of that moment: Hey, Ty, I was just wondering about something. Yeah, who’s your audience?

*

When I first started sending my collection out, I didn’t know what it was about. This was late 2018, and I was feeling the just-post-grad school rush to publish and the stupid, self-imposed deadline of my thirtieth birthday looming in the near future. I rushed. I hit submit. And submit. And submit. As was necessary, nothing came of it. Perhaps it’s the kind of mistake a writer needs to make to ultimately gain an understanding of their own work, one of those lessons learned the hard way. Regardless, it was still a mistake.

Even if I couldn’t talk about it, I did believe my book was about something. After all, I’d performed a series of exercises, such as writing imagined jacket copy—“…mirroring the constant state of liminality into which late-stage capitalism forces individuals…”—pitching the book over the phone to friends—“It’s as much about the ineffability of the now as it is the need to transcend ego…”—and devising a complicated index card system—“Each character is exhausted by desire!”—which taught me a lot about my own tendencies, but did not induce any sort of overarching enlightenment about my book, or how to talk about it clearly and succinctly. Maybe what I had was what I’d feared I’d end up with all along: twenty of my best stories, tied together only by the fact I wrote each one.

This process of learning what my work was about required a lot of letting go—of declarations, of stories themselves, and of self-imposed rules.As a proselytizer for story collections for nearly a decade, I have long talked about how the greats of the genre go above and beyond a random gumbo of disparate stories. Civilwarland skewers capitalism through a series of dystopian lenses drenched in humor. Birds of America presents a cast of lonely adults confronting the outsiderness they feel within their own families and communities. We the Animals is both a series of connected stories and a novel, and it says more about the role of love in a dysfunctional family than any great American domestic epic three times its size. In fact, over the five years I spent writing dozens and dozens of stories, I stopped using the term “collection” altogether, as it seemed to imply the pieces were simply thrown together in a pot.

Of course, in my case, they kind of were. Faking it, I called my manuscript a book of stories. The subtext was that a purposeful, thematic book of short fiction could be just as good, just as important, as the coveted, marketable novel. I still believe this, but the difference is that now I see that those early versions of my collection were not cohesive, pointed, or arranged in a way that felt, well, important.

This process of learning what my work was about required a lot of letting go—of declarations, of stories themselves, and of self-imposed rules. Now that the book is out, I’m almost certain I know what it’s about—home—and most crucially, I’ve learned that almost certain is as close as I want to get.

*

One of the pre-conceptions holding me back was that epigraphs were pretentious and to be avoided. I think I’d mixed a professor’s distaste for epigraphs on workshop submissions with something I heard a favorite rapper say about never opening an album with a guest verse: if it’s your album, your voice should be the first thing heard.

But then I went on a residency in the Adirondacks to revise some key stories, re-select which pieces I wanted in the manuscript (in five years I’d written almost fifty I liked, and needed to choose less than half), and re-conceptualize the book’s structure and thrust. I brought all my favorite collections with me and wound up re-reading Tell Me: Thirty Stories by Mary Robison. Midway through the book, there’s an unassuming four-page story called “In Jewel” about a high school art teacher weighing whether to marry her lawyer fiancé and thereby leave her coal-mining hometown of Jewel, West Virginia. The first-person narrator talks with wit, sadness, and obsessive attention to the tiny details that prove the town of Jewel is her true and studied home.

The only other time the narrator left Jewel was for a degree at the Rhode Island School of Design a decade earlier, where she had a nervous breakdown that only ended when she returned (“Back in Jewel again—surprise—I was fine”). At the top of a mountain that’s “on fire inside” there sits a giant boulder which is predicted to one day tumble down, crush a family’s home, and “tear out part of the neighborhood.” When I flipped to the final page, I saw something I had underlined years earlier, a gem of a sentence: “I like feeling at home, but I wish I didn’t feel it here.”

So many of my own main characters flashed to mind—Todd, taking residence at the demolition derby; lonely Rhonda building mailboxes shaped like famous architecture; Sabrina, flouting curfew to be with her mother in the dementia ward; Eve, trying to escape her assisted living facility. This was their dilemma too. Either they needed to find a new, healthier home, or they needed to let an old one go. This realization helped me return to my pile of stories and select only the ones that explicitly addressed the idea of “home,” which meant tough cuts to favorite stories (stories published in prestigious journals, stories containing some of my very best jokes and premises).

I left the residency with a revised version of the book that was closer to the goal of being cohesive and thematically pointed. But of course, my impatience pushed me to hurry toward new contest deadlines. I submitted again and again, wincing over every submission fee.

*

I had to let go of an arbitrary and restrictive belief that books weren’t about big, heavy nouns. “Loss” “Love” “Friendship” “Death” “Identity”—this was how books were talked about in blurbs and Library of Congress cataloguing, but that was all marketing BS, right? Real books, the kind I wanted to be known to write, explored more granular, esoteric, and literary subjects. I had to ask myself: what’s un-literary about home?

So in the book’s fourth iteration, I chose stories in the following categories: the loss of, the yearning for, or the frustration with one’s home. I added Robison’s epigraph, and I put “home” in the title. I chose the title of a story in the book (“Where the Rubies Live”) and then Machado’d the subtitle: Where the Rubies Live & Other Homes. Though this would not be the final title my editor at Sarabande and I would settle on in the fall of 2020, it was the title I needed in order to firmly plant my flag in the sand and give readers a lens.

I submitted it to Sarabande in January of 2020, for the second time (an earlier, unfocused version of the book had been a finalist for their annual story prize), and in July I got the call that they wanted to publish it. It was coming true, a dream I’d had since my 12th-grade English teacher introduced me to Miguel Street by V.S. Naipaul: I would publish a book of short stories with a respected press.

Home can become placeless, unbound by space. How freeing that can be.After all, the books that had lit the path for me—Tenth of December; Birds of America; We the Animals; Valparaiso, Round the Horn—were all about home. Did it mean I was an unoriginal hack? Maybe, but at least now I was being honest.

The question I should have asked myself that winter after my residency was not where should I send my manuscript, or can I afford another $40 reading fee, but rather: Why had I been writing so much about home? And more importantly, how had it taken me this long to realize it?

When I “went away” to a state school in 2009, it was only a 40-minute drive from where I grew up. Within a month of dorm life, I had driven back home six times, and by October, I learned my parents were splitting up. Though my father would own the house I was raised in for four more years, my mom was moving out, and the one place in the world where I felt safe was changed irrevocably. When it became too hard to watch my family fall apart firsthand, I stayed away, feeling nervous and lonely in my dorm room, studying my roommate’s class schedule so I knew when I could cry in private. This is also the time when I first started taking short story writing seriously. Those early stories were action-happy escapes into fantasy worlds and nightmarish surrealism. To quote Madeline ffitch’s one-of-a-kind collection Valparaiso, Round the Horn, “I was able to write stories with quite a lot of shooting off of guns.” I had never shot a gun and never will because I hate them. If only I could see that I wrote about what scared me.

It wasn’t until I was twenty-five and moved away from south-central Pennsylvania to south-central Minnesota that I began to write more realistic characters who were estranged from or fed up with the places they lived. I even started writing a series of failed stories set in a lightly fictionalized small town in York County, Pennsylvania (I swapped out “Dover,” my actual hometown, for “Deliver”). Whether I realized it at the time or not, the fathers in the stories spoke (little) and acted like my father, and the mothers were sad, missing their kids, and failing at love in middle age.

The children, teenagers, and young adults I wrote about all found themselves in liminal spaces—runaways killing time in hotel elevators; band mates stranded on the side of the road; a pre-teen stuck in a hotel because her house exploded due to a gas leak; children lost in the woods and selling knives to strangers in a quixotic attempt to save the family home.

It took leaving home to write about it. And that’s absolutely what I was doing, even if it took years of staring at my stack of index cards to see what was staring back at me.

*

The COVID-19 pandemic created for me a new restlessness about place, the future, and security. It wasn’t envy I felt seeing pictures of friends bunkering down in their parents’ houses to weather the storm of the pandemic, but fear. If my landlord pulled the rug out now and told us we had to find a new place, where would we go? If, god forbid, my partner died, where could I retreat in order to recover?

Identifying, describing, and sitting with my fears pushed me to have hard, necessary conversations with my atomized family. It made me think of Robison’s narrator from “In Jewell,” who feels frozen with indecision about whether or not to leave her hometown—staying feels so much like death (what with the boulder hovering over town), but leaving feels too uncertain.

This summer, I chose uncertainty and took a job in the high peaks of the Adirondacks. It began this fall, and in September, two months away from the release of my first book, my wife and I moved 400 miles north, to a town a twentieth of the size of the city we were leaving.

I don’t yet feel at home here in Saranac Lake. However, when I recently left for a week, I started feeling something unfamiliar—it was new, pure, and nearly debilitating. Homesickness. What I found odd was that when I closed my eyes and thought of Erin and Petey (our dachshund), we were not in any specific location, apartment, or town. We were simply holding each other. My vision was of their faces, not of walls, furniture, or windows; it was evidence that home can become placeless, unbound by space. How freeing that can be.

I don’t know if I’ve found freedom yet; I suspect the purest form of belonging and security comes from within, a comfort with being alone in the home of one’s self, where the liminal space of the daily becomes a simple, quiet now. Now, my work is to prioritize not the publication of another book, but the peace of being who I am no matter where I’m located.

These days, when I do get the urge to write, I ignore that voice asking what it’s about, who my audience is. I don’t know. And that’s okay because on some deeper, truer level, I do know. It just might be awhile before I can tell you about it.

__________________________________

Eternal Night at the Nature Museum by Tyler Barton is available via Sarabande Books.