Why Byzantium? Studying the Art of the Middle Ages as a Queer Latinx

Roland Betancourt on the Origins of His Latest Book

“Why Byzantium?” It’s a question I have often been asked as a queer, Cuban-American studying Byzantine art.

In the fall of 2010, I attended a party filled with graduate students in art history from Harvard and MIT. As a second year PhD student at Yale, who had almost gone to MIT instead, I was excited by the prospect of meeting fellow, young art historians.

As the apartment began to fill, the host came up to me and introduced herself. We chatted a bit about where we were from and where I was studying. And, then, she moved on to the customary line in any conversation between academics: “What do you study?” Innocently, I replied, “Byzantine art.” I expected the conversation to move on from there, as it went for most people: making small talk about advisers and colleagues, quietly judging each other for the intellectual rigor and nuance of one’s research projects. But, my host stopped, asking with shameless dismay, “Why Byzantium? Why don’t you study Latin American art?” A part of me has existed in this moment for the past ten years, never fully knowing why.

At this point, a year into my graduate career, this had actually become the expected route of any conversation: a combination of quizzical intrigue about my focus on Byzantium and the imperative that I study Latin American art instead. This too was always inevitably met with three questions, listed here in order: “But, you don’t look Hispanic,” “Which one of your parents is Cuban?,” and, of course, “But, why is your name French?” My answers to these questions were ultimately dissatisfying to all who asked them.

Back at that party, standing in a room filled with Harvard, MIT, and Yale PhD students, I recall that no one there worked on Latin American art, at least at the time, and that no faculty member at any of our schools focused on this area of study. In other words, had I worked on Latin American art, I would not have been standing in that room with this illustrious crowd. That is how it felt then, and how it would feel for the rest of my graduate career.

Over the years that followed, I cannot remember anyone ever telling me that I could not work on issues of sexuality and race. But, what was impressed on me in passing conversations was that such studies were lacking in scholarly rigor, wholly anachronistic, and had no place in serious academic scholarship within art history. In fact, many of these comments are still a part of my academic life, often spoken by colleagues who might—in other spaces—fashion themselves as allies.

This way of thinking had certainly been ingrained in me since my time at the University of Pennsylvania, and it became more of a prohibited area of study rather than a space of potential consideration for my work. I was already radical enough, in my own special ways. All this felt far too precarious for a first-generation American, queer, and Latinx scholar.

I came to learn queer theory illicitly. My partner at the time passed along syllabi from their classes at Harvard that opened my world to a whole realm of scholarship, one that was thriving with the intellectual complexity and depth that I had long yearned for. Reading the work of queer and Latinx scholars, from Elizabeth Freeman to José Esteban Muñoz, radically changed my world. It not only showed me that a whole field of research existed, but it allowed me to imagine for myself a new, luminous horizon. This work seeped into everything I did, my discussions of art, temporality, visual analysis, writing, and argumentative structure. To my advisers, this work was invisible, buried in the methodology section of my dissertation and appearing idiosyncratic at best.

Leaving graduate school, I immediately found myself far from Yale at the University of California, Irvine. It was, frankly, a jarring change. Living in Los Angeles was disorienting. Pool water glistened in a harsh sun beside dusty old concrete and dilapidated lead windows at an ill-treated apartment building from the 1930’s off Melrose. Living in Los Angeles also felt like home. The threat of hurricanes replaced by the threat of earthquakes, and here most people didn’t quite understand my accent or dialect of Spanish.

In Hollywood, no one asked you what you studied, and no one cared that you were a professor or had a PhD. I wasn’t a scholar, a researcher, or a historian here, I was simply someone who taught some classes, somewhere down south. It was stifling, but also utterly liberating to be so far away from the voices of stricture and doubt that guided my research before.

In Los Angeles, I felt forgotten and alone. I was a child free to play without supervision. I must have written six academic articles that first summer, which would trickle through peer review and publication for the next two and half years after that. In that freedom, I began to think again of what was necessary: unholy ideas dilated without chastising. And, “side projects” on queer theory and Byzantium began to fill documents and notepads scattered on the dining room table. They filled emails to distant colleagues and midnight chats. They took over my teaching as I began to teach my students about queer monks, trans saints, the brutalities of empire, and racialized violence. But none of it still would make it into scholarly print.

Reading the work of queer and Latinx scholars, from Elizabeth Freeman to José Esteban Muñoz, radically changed my world.Two years after my arrival in Los Angeles, I was awarded a prestigious fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey—one of my major pipedream goals, second only to winning a MacArthur Grant. At this point, I had two book manuscripts finished, and another in the works. But it was all work emerging out of my dissertation. And so, I was yoked to that text’s staid commitments. Those commitments were wearing on me.

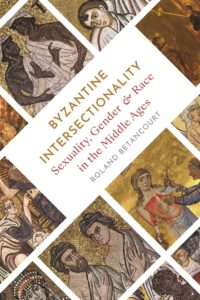

Riveted by the freedom offered by the Institute and as a familiar hatred spewed across our country, I ditched the project I had applied to the fellowship to pursue. Instead, I drafted up a book entitled Byzantine Intersectionality collecting all those notes and narratives scattered across the margins of my research on Byzantine art, culture, and theology. From these scraps, I worked in the ensuing months to flesh out five narratives about the unexpected realities of medieval life, detailing sexual consent, reproductive choice, gender variance, same-gender desire, and racialization.

I presented the first chapter of this book on Election Day 2016 on the topic of sexual consent in narratives of the Annunciation. It was met with warm enthusiasm and silent reservation. The next day, a colleague came up to me at lunch and looked at me, frankly, telling me: “Well, your book matters a lot more today than it did yesterday.”

It is easy to assume this book emerged out of the 2016 Election. But the reality was that it existed long before this moment. As a queer Latinx, 2016 confirmed truths painfully, but it only reasserted the reality of the world in which I had existed my entire life and which my schooling had meticulously, gracefully, and discretely enforced.

As I continued writing over the following months, a lot changed in the world and in my personal life, making each chapter poignantly important. There was an urgent rush to show that there was no newness or invention to the lives, subjectivities, and loves of my present. Over the years, this book became more painful as I was filled with guilt that I had not written it earlier. That I had not started earlier. And as I presented this work, I came to know who my colleagues really were: the ones who denied the existence of trans people in the middle ages or who denied queer theory as a valid model for historical inquiry. And I have lost jobs offers for these reasons.

In that freedom, I began to think again of what was necessary: unholy ideas dilated without chastising.When I discuss my book, I tend to describe it self-depreciatively as a “provocation” to my field, or as a book meant to “generate conversation.” Certainly, I firmly believe that my goal has been accomplished if in ten years my book is wholly outdated, surpassed by rich new scholarship in queer and trans studies. But, the reality of is that I find absolutely nothing provocative, controversial, or unique in my book. It is nothing more than a sincere reading of primary sources in their original language, depicting a candid look at the first millennium and a half of Christianity from the vantage point of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Truly, the only thing different about this book from any other one in my field is that it was written by a queer Latinx. When confronted with the complexities of sexuality, gender, and racialization, I as a historian have never assumed a white, cis, heterosexual as my historical subject.

Instead, I poignantly recognized the words of an 11th-century philosopher describing his gender as neither feminine nor masculine, like an instrument whose strings are both high and low pitched, including elements of both but being only neither. I recognized the pleas for articulating same-gender communities, which not only acknowledged the ways in which love sometimes slips into sex, but also showed a respect for people’s gender, not for what sex they were assigned at birth.

It is not radical to see why writers might have become concerned with Mary’s consent in discussing the Incarnation of Christ, placing her willing consent as the hallmark of Christian salvation. It is not radical to recognize how women across time have sought the best medical care for their bodies, preserving ancient knowledge about contraceptives and abortive practices, while doctors advocated for the termination of pregnancies to save a woman’s life.

None of these ideas are radical or revisionist, they are deeply sincere.

Ultimately, it is hard for me to explain from where this book began. Over the years, it becomes clear to me that I could not have not written this book, even if I had tried to resist it. Byzantine Intersectionality emerged from the simple reality of existing in this world as a queer, Latinx historian of Byzantine art.

“Why Byzantium?” Why would a queer, Latinx person study Byzantine art? The answer to this question is not about the person who studies Byzantium. The answer to this question is a declaration as to what our history and scholarship have to gain from that person.

__________________________________

Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender, and Race in the Middle Ages by Roland Betancourt is now available via Princeton University Press.