A few years ago, following the modest success of a book I had edited,(1) I was invited to give a series of lectures at a university in a small and somewhat remote city in central Europe which I shall not name. (There is no great reason for my reluctance to withhold the name of the city. Suffice to say that some of the incidents I will go on to relate, and the people mentioned in them, may want to maintain a veil of modesty. Those who know the city will no doubt recognise it; I trust their discretion.) A Professor at the city’s well-established university had been much impressed by the book, and had contacted me about the possibility of delivering some lectures on the theme. After various proposals were entertained, I ended up being extended an invitation to give a series of ten lectures on lost, forgotten or unjustly neglected books (rather than lost, forgotten or unjustly neglected writers, which had been my previous field). Flattered by the invitation and the Professor’s interest and enthusiasm, I jumped at the chance, especially seeing as the terms they were offering were more than generous. It was a good time to be leaving, as well. Endings—whether those of books or relationships—can make good beginnings.

So that is why I found myself waiting at a station in a city whose name I could hardly pronounce, and where I did not speak a word of the local language, waiting for someone I would not recognise to take me somewhere I did not know.

This, I thought, this is good.

*

I walked along the station platform and ignored the stalls selling coffee, gigantic pastries and newspapers with disturbingly few vowels in their mastheads. I saw men dragging cases, a large family shouting at each other, commuters scuttling, two lovers breathlessly reunited. One or two uniformed drivers stood around smoking (yes, this was a place where it seemed you could still smoke in a railway station without fear of reproof), holding signs for hotels whose names I had seen in guides to the city. There were none for me, nothing with my name on it, the driver I had been promised apparently now long since departed due to the interminable delay. Obviously, there was the temptation to claim that I was Herr Vandervelde or Signor Bandera or Dr Flannery, not least to see how long I would be able to get away with the deception, but the temptation was brief. I am not a good actor, or liar. I get anxious too easily. I have a fear of being found out.

John Berger has written that “of all nineteenth-century buildings, the mainline railway station was the one in which the ancient sense of destiny was most fully re-inserted . . . in a railway station the impersonal and the intimate coexist. Destinies are played out.” I waited to see what destiny would be played out for me, relishing my intimacy against the impersonality. In a French railway station, the hall immediately before the platforms is called la salle des pas perdus: the room of lost steps, a place which retains the echoes of the footfalls of those who crossed it and have long since vanished. As I waited there uncertainly, I wondered if they used the same expression in this country. I paced back and forth, losing steps, in an attempt to appear at least somewhat purposeful. If you have a purpose, I find, people are far more likely to ignore you.

After some time I remembered I had been wise enough to write the name and address of the hotel where I was to spend my first few evenings in the city on a slip of paper that I had stashed in my wallet. I found it folded between a few unfamiliar bank notes with improbably large numbers on them and decided I would walk out of the station, find the taxi rank, hand the paper to a driver and let myself be carried to my destination.

1. The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (Melville House, 2014).

__________________________________

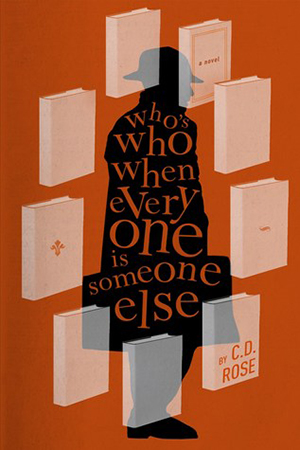

From Who’s Who When Everyone Is Someone Else. Used with permission of Melville House. Copyright © 2018 by C.D. Rose.