Whit, Sugi, and Special Guest Jabari Asim Reflect on the Podcast’s Indelible Interviews and Controversies from the Past Four Years

Fiction/Non/Fiction at 100 Episodes

For the 100th episode of Fiction/Non/Fiction, co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan hand out the first-ever “Nonnie Awards” for the podcast’s standout moments from the past four years. Then author, poet, and playwright Jabari Asim reflects on how the discourse on racism and police brutality has shifted since last summer. Asim also reads from his upcoming novel Yonder, out in January 2022.

To hear the full episode, subscribe to the Fiction/Non/Fiction podcast through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player above. And check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel and Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel. This podcast is produced by Andrea Tudhope.

*

Selected readings:

Jabari Asim

Yonder (out January 2022, available for pre-order) • Stop and Frisk • We Can’t Breathe: On Black Lives, White Lies, and the Art of Survival • Mighty Justice

Others

Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration by Ruben Jonathan Miller • The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones • The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas • Watchmen (TV series) • Fiction/Non/Fiction, June 2020: Black Stories Matter: Terrion Williamson and Jabari Asim on Narrative During the George Floyd Protests • Fiction/Non/Fiction, February 2020: Coronavirus and Contagion: Laurie Chen and Richard Preston on Writing About the Spread of Disease • Fiction/Non/Fiction, March 2019: C. Riley Snorton and T Fleischmann Talk Gender, Race, and Literature • Fiction/Non/Fiction, September 2018: Garrard Conley and SJ Sindu on the Mainstreaming of Queer Identity • Fiction/Non/Fiction, January 2018: Literary Color Lines: On Inclusion in Publishing • Fiction/Non/Fiction, November 2017: We’re All Russian, Now: Talking Russian-American Politics, and the Enduring Appeal of Russian Literature

*

Excerpt from a conversation

between Whit and Sugi:

Whitney Terrell: I want to talk about the Fiction/Non/Fiction awards.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Your idea? It’s a very interesting idea.

WT: Do you not like this idea?

VVG: I like this idea. It’s hard. It involves judgment. I’m very good at being judgey. It might piss people off, but making choices is a way of generating discussion.

WT: Wouldn’t it be great if there was somebody sitting around going, I did not win a Fiction/Non/Fiction award, boy, does that make me so mad.

VVG: [laughing]

WT: Like all the people sit around who didn’t get NEAs—like me—you know, feeling bad about it. All right. I have an idea for what we should call these awards.

VVG: Should I be happy or terrified?

WT: Well, why don’t you listen to my idea? I think we should call them the Nonnies. Eh? Eh?

VVG: [pause] Okay, so…

WT: Do you have something better?

VVG: I do not have anything better. I guess we can go with that. But whatever we call them, our first and honestly most important Nonnie will be the Shashank Murali We Don’t Need No Education Award, given to the topic area that was most relevant to the Fiction/Non/Fiction podcast and thus the world over the past four years. The nominees are all up on our website under the By Topic for Educators tab—thanks to our former intern, Shashank Murali, who is a student at the University of Minnesota. You should all visit this tab, by the way, especially obviously, if you’re an educator. It’s sort of a “if you liked this episode of the podcast, you might also want to assign this one” kind of scenario. And they are drumroll please [drumroll] COVID-19, climate change, industry insider, race, and gender and sexuality. Is there anything there that you would like to add?

WT: I mean, I understand why we grouped those on the website in that way. And I think that makes sense to me. The only thing that I would add—I think authoritarianism was something that we did a good job of covering. And, you know, we wrote about authoritarianism and the forces of authoritarianism rising in Sri Lanka, in India, in Poland, in the United States and Myanmar. And in Hong Kong. Am I missing anything? Those are the ones I remember specifically talking about. That’s a lot of episodes. And a lot of the Trump-related stuff was really sort of about authoritarianism and what it meant and how he was adopting ideas of authoritarianism. But this wasn’t clear from the beginning of his presidency, that that’s what was going on or that it was linked up to other countries. I mean, when we did that episode, with Steve Yarbrough, about the rise of authoritarianism in Poland, which was fairly early on, I had no idea. And I found that one of the most scary episodes that we did, because I did not understand that this movement was happening already, and in a country as large as Poland and recently democratic, and you know, you learn about it all the same things happening in Hungary. And that started to feel like a growth of a movement that I don’t think is over. And so I feel like I don’t know if that’s the most important topic, but I would include that in our group.

VVG: Yeah, that makes sense. I don’t know if this exactly falls under that umbrella, but your friend Tom Frank came on the show a couple times and talked about populism, which connected to my understanding of authoritarianism in interesting ways. I found that episode to be really illuminating. To think about the ways and the meanings of populism being inverted over time, through history, and the ways that Trump was and wasn’t a populist in the original way. That was surprising to me. And of course, doing the Sri Lanka-related one—we got to have some amazing reporters on the show, which I was so happy about. The show obviously features a lot of fiction writers, poets, but then I think, pairing that with reporters and letting the reporters who don’t often get to talk about their thoughts on craft in the same way that, you know, talking about craft is the bread and butter of creative writing a lot of the time and I don’t know that journalists get invited to talk about that sort of stuff on a show like ours often. And so making space for that, I learned a lot about how I might think about writing about authoritarianism, or race and gender, or, you know, leaderless movements like the one in Hong Kong, I remember Javier Hernandez, talking about what it meant to try to write about a movement that was trying very self consciously to not have an icon at its head. And to think about those ideas and apply them to fiction. That has been really satisfying for me almost regardless of which topic we were talking about, I found that I was able to take that away from almost everyone. But what do you think was the most covered? Or most important?

WT: Well, I can remember different episodes for each. We’re going to talk about Richard Preston in a minute. I thought we had a really good episode with him that predicted what was going to happen with COVID-19. And then we had a Danez Smith episode that was really good about living under quarantine that I that I liked. We’ve had Nathaniel Rich to talk about climate change and Juliana Spahr.

VVG: Yeah, the poet Juliana Spahr.

WT: Her episode was really good. And that’s not the only climate change stuff that we’ve done.

VVG: I loved Emily Raboteau’s stuff.

WT: Yeah, yeah, that’s who I was thinking of. But I still think this podcast’s signature is talking about race and American society, and race and how it affects the way people write. We’ve talked about it in the publishing industry, we’ve talked about it in policing. We’ve talked about it from the very first episode, which was about Colin Kaepernick, all the way up through our last episode with Adam Serwer. This podcast comes out of our friendship with and learning from James Alan MacPherson, and this is something that Jim was always constantly talking about—if you want to understand American society, you’ve got to think about it in terms of race. I feel like that, to me, is our biggest throughline.

*

Excerpt from a conversation

with Jabari Asim:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: We started our very first episode by listing the names of Black men who had been shot by the police, and the godfather of our show is our former professor James Alan McPherson, who taught Whitney and I separately, shared many of the same texts with us, and taught a lot about the throughline of race in American life in history.

Whitney Terrell: Which is why we wanted to have you back for this 100th episode. And one of the things we talked about when we spoke to you—and we’ve talked about with a lot of other guests like Mat Johnson, Brit Bennett, Victor LaValle, Danez Smith, Dwayne Betts, Timothy Yu and most recently Adam Serwer—we talked about narrative, and how narrative has represented race and policing. That’s something that we discussed a lot in the episode that you were on. I wonder if you feel like these norms of narrative and the way we think about narrative on this particular issue has shifted during the year that passed since you were on the show, in a positive or negative way.

Jabari Asim: One of the operative words there, though, is “we.” When we talk about do we look at the narrative differently, if you look at African Americans, we’ve always looked at the narrative differently. Mainstream America seems to be still very much divided politically. So I don’t necessarily think that our efforts to shift the narrative have really moved the needle as much as would be necessary. But we are seeing some little indications. For example, in some of the media reports of late, I’ve seen reporters and editors more willing to say racist, for example, as opposed to allegedly racist, or alleged racist comments. And now with growing frequency, seeing racist comments labeled as racist comments or racist behavior. This is a small thing. But if you’re African American, and you’ve been monitoring this kind of discourse for some time, you notice these shifts, and that’s very different. And it’s connected, partly, to newsrooms responding to calls for diversity. We don’t just mean reporters of color, we mean people in decision-making positions of color, who can make a call on a headline, on a description of behavior or commentary. And I think that’s where you’re seeing the influence, where the narrative is being regarded somewhat differently. So, small indications like that, there are some changes, but by no means should those indications be read in my view as a substantial movement of the needle.

VVG: I was listening to the episode that we taped with you last year, and I noticed that you mentioned the date 1619. You didn’t specifically reference The 1619 Project that Nikole Hannah-Jones led, but you mentioned that date and I was thinking about how, over the past year, I’ve heard that date more and more, and I was trying to decide if I could count that as one of the norm shifting. In recent days we’ve seen Nikole Hannah-Jones, go through really racist treatment from the Board of Trustees and a donor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she had initially been recruited for a tenured position, a Knight chair in journalism, and she decided to go to Howard, which is an HBCU. And I was thinking, as I was listening to our previous conversation, about everything that you’d said about, who is the audience? Who has access to write? What do those norms mean, and who are they for? Her dramatic and profoundly moving decision to go to Howard, for me, it was like she was saying that it wasn’t her job to fix that norm.

JA: Yeah, she also expressed an exhaustion of having to devote so much energy to proving that she belonged in these white spaces, and she didn’t want to do that anymore. As a longtime African American journalist, of course, I can totally relate to that. The other good side of her movement to Howard University is that it does shine a necessary light on the type of journalism that’s being developed in places like Howard University, Hampton University, and most notably, I would say, Morgan State University in Baltimore, where they have a really world class, African American led journalism program, and they’re turning out really talented people who are going to do that work, in terms of shifting the narrative. But of course, the hostility toward Nikole Hannah-Jones derives from this fury that she has stirred up by daring to so openly want to change the narrative in terms of the relationship between white supremacy and American history. And, of course, we need to point out that an African American at the top of the masthead at the New York Times helped make that possible. There’s not an African American at the top of the masthead at the Los Angeles Times. So that’s beginning to happen, but it’s all overdue. It’s so overdue. I don’t want us to waste a lot of energy patting ourselves on the back and talking about how far we’ve come when we have so far to go. It’s an ongoing battle. From the earliest African American journalists, John Russwurm, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, that’s exactly what they were doing. So Nikole Hannah-Jones is doing wonderful work, but really following in their footsteps. And that resistance has always been there. So it’s a continuing struggle.

VVG: Last year you said, “the weight of societal custom shapes our portrayals.” Since then, many things have happened. I’m curious how you think the conversations and events of last summer and what happened after are beginning to appear in our culture, and how important it will be in the long run that Derek Chauvin was convicted and sentenced to jail.

JA: It’s important to note that shortly after George Floyd was killed, Jacob Blake was shot and left paralyzed by police. There’s rhetoric and then there’s actual consequences and changes in police behavior. The jury is still very much out on that. It’s common sense for African Americans to regard any hint of PR in the direction of police becoming more sensitive with healthy skepticism. I would say that it’s very early in terms of the post George Floyd period for us to be making large scale assessments. I think we just need to be open eyed, and continue the struggles to create and implement systems in which police are actually responsible to their alleged constituencies.

VVG: So last time we were talking about cowboy narratives and the way that people tell stories to let themselves off the hook. I hope—and maybe this is just an aspirational hope—that one of the things I am seeing slightly is narrative, even mainstream narrative, getting messier, less conclusive, more willing to accept a real world in which things are untidy, unfair. I think of narratives like The Hate U Give, and “Watchmen.” And Derek Chauvin was convicted, and then there’s such a lack of accountability in so many other ways. This morning I was scrolling through my timeline, and I saw a story that was sort of like cop PR about a police officer arresting a DoorDash driver, but then completing his order. And I was like, I don’t care. I was like, how did this make it into the newspaper? The narrative around who the police are does seem to be moving away from that kind of tidiness or “one man can save the day.”

JA: No question. I totally agree with you. Another area of improvement that I’ve seen—there’s so many initial reports in mainstream newspapers when there is a police shooting that seem to almost copy the police report word for word. But so many of these reports have been exposed as the fiction that they are that newspapers are beginning to put that kind of language and scrutiny into those initial reports and on television as well. So I agree with you. I think that is a positive step. And I think your word messy is appropriate. They’re taking more care to disclose the messiness of the circumstances surrounding these shootings and how long it takes to actually ascertain the facts.

__________________________________

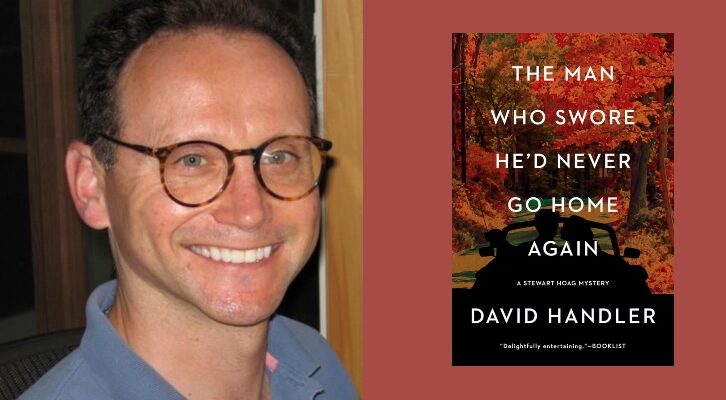

Transcribed by https://otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Andrea Tudhope. Photo of Jabari Asim by JennyMae Kho. Photo of Whitney Terrell by Leslie Many. Photo of V.V. Ganeshananthan by Annette Hornischer, courtesy of the American Academy in Berlin.