When Tom Seaver Came Into the Big Leagues He Came in Pitching

(But That Didn't Stop Lou Brock From Telling Him to Fetch a Coke)

There were only 5,379 fans at Shea Stadium when Tom Seaver took the mound for the second time, April 20, 1967, to face the Chicago Cubs. His opponent, the wily thirty-seven-year-old lefty Curt Simmons, was in the final year of his career but was still capable of keeping a team at bay for five or six innings—which is what he did on this day. The score was locked at 1–1 going into the sixth when the Mets got to Simmons and provided Seaver a welcome cushion, on a single by their increasingly impressive-hitting young outfielder Cleon Jones, followed by a sacrifice bunt, an RBI single by the veteran third baseman and 1964 National League MVP Ken Boyer, a double by Tommy Davis (like Boyer, a former National League All-Star acquired in trade by Devine), and a sac fly by Swoboda.

Buoyed by the 3–1 lead, Seaver stranded a couple of Cubs base runners in the seventh. But when he gave up a leadoff single to shortstop Don Kessinger in the eighth and retired second baseman Glenn Beckert on a hard-hit liner to left field, once again, here came Westrum, along with Boyer over from third and Harrelson from short.

“How do you feel, Tom?” Boyer asked.

Looking at Westrum, Seaver wanted to say he was fine. But he also didn’t know if he had enough to get through another inning, and right now he was the winning pitcher of record.

“I’m pooped, Wes,” he admitted, while also noting that the next Cubs batter, outfielder Billy Williams, a future NL batting titlist and Hall of Famer, had tripled in the only run off him in the third.

Rookie Don Shaw, Seaver’s road roommate, came in and got Williams to hit into an inning-ending double play, and then, after the Mets scored three more runs in the bottom of the inning, retired the Cubs in order in the ninth.

Westrum would later tell the writers that what impressed him just as much that day as Seaver’s 7⅓ innings of one-run, five-strikeout, walk-free ball was his honesty. “He could have selfishly told me he was okay, and I probably would have left him in, but he knew he was about out of gas, and that wouldn’t have been fair to the team,” the manager said.

Five days later, Seaver faced the Cubs again, this time at Wrigley Field. He pitched ten innings, yielding only four hits and one unearned run for a 2–1 victory. He was 3-1 with a 2.21 ERA for his first six major-league starts when he faced the Braves—and his boyhood idol Hank Aaron—in Atlanta on May 17. In their first encounter, with one out in the first inning, Seaver got Hammerin’ Hank to ground into an inning-ending double play on a sinking fastball. The next time up, leading off the fourth, Aaron struck out looking. In 2016 Seaver remembered strutting back to the dugout after the inning, being giddy with joy.

“You can just imagine how I felt at that time, having retired Henry on a double play and a strikeout looking,” he told me. “Growing up, the Braves had always been my favorite team because Henry was my favorite player. Henry was always first with me, and I don’t find it strange at all that a white boy who wanted to become a major-league pitcher would most identify with a black hitter. I thought of Aaron as excellence. He was so much fun to sit and watch because he was so damn consistent, dedicated, and yet capable of making the game look so easy to play. Confidence flowed out of him.”

That was never more evident than in his next at-bat, in the sixth, with the Mets nursing a 3–1 lead. After a one-out single by Felipe Alou, Aaron clubbed a long home run to left field to tie the score. The pitch was the same sinking fastball Seaver had struck him out on two innings earlier. Seaver had always prided himself in remembering hitters’ tendencies and weaknesses and then capitalizing on them. On this occasion, he learned a lesson that hitters, especially hitters like Bad Henry, also remembered.

“When Seaver came into the big leagues, he came in pitching.”

Meanwhile, the rookie pitcher helped his own cause with the bat, going 3-for-3 with a pair of run-scoring doubles off Braves starter Bob Bruce. The contest remained tied until the bottom of the ninth when catcher Joe Torre, playing with a broken index finger, led off with Atlanta’s third homer of the night for a 4–3 win. (Over the course of his career, Aaron was 18-for-82, .220, with 5 homers and 14 strikeouts against Seaver.)

In a July 2017 interview, at the Hall of Fame, Aaron recalled those first impressions he had of Seaver.

“Tom was just so dedicated. He came up to the big leagues knowing what baseball players were all about. I can’t think of anyone else in my twenty-three years in the big leagues who was as competitive as he was,” he said. “I remember that first time we faced him, somebody on our team said, ‘This kid coming out of California, right out of college, he’s not ready for the big leagues.’ And then I went up to the plate, and I said, ‘I don’t think you’re right. This kid is ready for the big leagues and probably ready for the Hall of Fame.’” Aaron laughed. “He was that good. I don’t know who his teacher was, but to me I would have to say he was more than ready for the Show.”

Seaver made it a point of getting to know Aaron, and, through the years, they talked often, particularly about what might have been.

“He seemed like he wanted to meet me, and I wanted to meet him,” Aaron said. “We had a great relationship. It was not one of those deals where we shook hands and he said, ‘Well, I’ll take it easy on you.’ We were friends until he put on that uniform and got on the mound, and then I was his enemy. I had heard all about him because of that draft that came as a result of the Braves’ illegally signing him. I think we would have won a few championships if he’d been a pitcher on our Braves ball club, don’t you?”

In five starts in May, Seaver pitched three complete games, winning two of them and giving up more than three runs only once. On July 3 he hurled his ninth complete game of the season, a 5–3 victory over the Giants at Shea Stadium, giving him a 7-5 record with a 2.70 ERA. After the game, he learned he was the lone Mets player to be selected to the All-Star Game in Anaheim, California, on July 11.

“When Seaver came into the big leagues, he came in pitching,” said Billy Williams in a July 2018 interview at the Hall of Fame. “And if you picture him, when he threw the ball, he always dragged his knee—that knee would always go to the ground, and he threw the ball low. He seldom gave you a good pitch to hit. And he knew how to get people out.” As Ron Darling, a standout starter for the Mets from 1983 through 1991 and later a baseball TV analyst, observed: “Because of the way Tom was built, stocky, strong, six foot one, he had the ability to do a thing that we call the ‘drop and drive.’ Every pitcher wants to do it, but few can because you have to be built a certain way. I’m six feet, Tom was six one. I could never drop and drive because it was just too hard to get that low. When you watched his body, he was just so powerful from the waist down and was able to use his lower half.”

Despite the quiet admiration he was receiving from his peers, when Seaver arrived at the National League clubhouse and looked around the room at the sight of Aaron, Clemente, Mays, Drysdale, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, Bob Gibson, and Ernie Banks all suiting up as his teammates for the day, he felt like Alice in Wonderland. Only two years earlier, he’d been pitching for USC, and now here he was in the presence of some of the greatest players baseball had ever known—as an equal, no less, at least in the minds of the players, coaches, and managers who had selected him to the All-Star Game.

It took only a couple of minutes to jolt him back to reality. As Seaver was looking around the room for his locker, Lou Brock, the speedy St. Louis Cardinals outfielder and soon to be the preeminent base stealer in baseball, approached him. “Hey, kid,” Brock said, “mind fetchin’ me a Coke?”

At first, the embarrassed Seaver didn’t know what to say, so he dutifully went over to the soda cooler, pulled out a Coke, and brought it back to Brock. “Here you are, Lou,” he said, putting out his hand. “By the way, I’m Tom Seaver.”

Now it was Brock who was momentarily embarrassed. Then they both laughed. But Seaver never let Brock forget the unintentional slight. Every year at the Hall of Fame inductions in Cooperstown, whenever he’d see Brock in the lobby of the Otesaga Hotel, he’d holler out: “Hey, Lou! Fetch me a Coke, will ya?”

“Being in that clubhouse and seeing all those guys who, as a baseball fan, I always had the impression were super beings, not human, I was really in awe of it all,” Seaver recalled to me in a 2016 interview.

“But my biggest thrill, before the game itself, was when Sandy Koufax came into the clubhouse to visit his old friends and sat down beside me.” The three-time NL Cy Young Award winner, who led the league in ERA from 1962 through 1966, had shocked the sports world by retiring in November. Though just thirty-one years old, Koufax had been bedeviled by chronic arthritis in his valuable left arm, and he quit the game to prevent injuring himself permanently. Now he was trying his hand as a baseball announcer for NBC-TV. “All of a sudden,” marveled Seaver, “here we are talking like two ordinary guys, and he’s chatting with me like I’m his equal.”

Seaver began to sense the Mets played harder when he pitched.

Before the game, Seaver told the New York writers he didn’t expect to see any action. Back in those days, the leagues played the All-Star Game to win, and it was not uncommon for starting pitchers to throw at least three innings. As Seaver pointed out, with Gibson, Drysdale, Marichal, and Ferguson Jenkins, all future Hall of Famers, not to mention four or five other starting pitchers with far more experience than he had, it didn’t figure there would be enough innings for the rookie.

As it turned out, there were.

In what became the longest All-Star Game in history (until matched in 2008), the Americans and Nationals engaged in a 1–1 stalemate into the fifteenth inning. While National League manager Walt Alston made use of all of his heralded aces, including Marichal, Gibson, Drysdale, and Jenkins, plus two others, Mike Cuellar of the Houston Astros and the Philadelphia Phillies’ Chris Short, once it got to the eleventh inning, his American League counterpart, Hank Bauer, handed the ball to Catfish Hunter of the Oakland A’s, and left it with him. In the top of the fifteenth, Hunter finally buckled, yielding a one-out solo home run to the Cincinnati Reds’ Tony Perez.

As soon as the ball cleared the fence, Alston signaled down to the bullpen for Seaver to start warming up. For the Mets rookie, it was a “Who, me?” moment. After being assured that Alston wanted him and not veterans Claude Osteen or Denny Lemaster to protect the game, he jumped up and began throwing, his heart pounding and his stomach churning. Nancy and his parents were in the stands, and he could only imagine what they were thinking, seeing him warming up in anticipation of getting the save in his first All-Star Game.

As Seaver came out of the bullpen, he remembered jogging past Clemente in right field, and trying his best to slough off the pressure he was feeling by yelling, “Let’s get three and go home here!”

“That’s right, rook,” Clemente replied. “Go get ’em, keed!”

Then as he got to the infield, he said to Pete Rose at second base, “How about you pitching and me playing second?”

The Cincinnati Reds’ star, in the middle of his third straight .300 season, laughed.

“That’s okay. I’ll stay where I am. You’ll get it done,” he said assuringly.

After retiring leadoff hitter Tony Conigliaro on a fly to left, Seaver peered down at his Boston Red Sox teammate, Carl Yastrzemski, wagging his bat at the plate. The menacing left-handed hitter would go on to achieve the rare Triple Crown, leading the league in batting average (.326), home runs (44), and runs batted in (121), and, almost anti-climactically, win the 1967 American League Most Valuable Player Award that season. As Seaver told me years later: “I wanted no part of Yastrzemski, and there was no way he was getting a pitch to hit.”

He didn’t. After walking Yaz, Seaver retired Detroit catcher Bill Freehan on a fly to Willie Mays in center and closed out the game in spectacular fashion by striking out White Sox outfielder Ken Berry, pinch-hitting for Hunter, on a high, midnineties fastball. “That,” said Seaver, “was my new highlight of the day. In the clubhouse afterward, the Aarons, Mayses, and Cepedas were all coming up to me and shaking my hand, and my eyes, I’m sure, were as big as saucers.” He was especially taken by the raucous celebration in the NL clubhouse afterward. Even though it was only an exhibition, and most of them had played in numerous All-Star Games, the National Leaguers, who were in the process of winning nineteen out of twenty All-Star contests from 1963 through 1982, took it seriously. On the plane flight home, Seaver said to Nancy, “Those guys are all winners. They take pride in winning. That’s what we’ve got to start instilling with the Mets.”

Whether or not it was just his imagination, Seaver began to sense the Mets played harder when he pitched. He wasn’t the only one who took winning to heart, as evidenced in his April 25 extra-innings win against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Seaver was pitching a 1–0 shutout when, with two outs in the ninth, Bud Harrelson botched a grounder to short by Ron Santo, allowing the tying run to score. The next in- ning, Seaver led off with a single, was sacrificed to second by Cleon Jones, and scored the go-ahead run on a single by Al Luplow. After retiring the Cubs in order in the bottom of the tenth for the complete- game victory, he came into the clubhouse and found the disconsolate Harrelson sitting alone at his locker, his head buried in his hands. “These guys do care,” Seaver thought. “At least some of them do.”

Seaver, 9-8 after the All-Star break, ended the 1967 season at 16-13, making him the first Mets starter to surpass thirteen wins. His 18 complete games, 251 innings, 179 strikeouts, and 2.76 ERA also set Mets records. In 8 of his 13 losses, he gave up 4 or fewer runs. Seaver was finishing up classes back at USC when, on November 20, three days after his twenty-third birthday, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America overwhelmingly elected him National League Rookie of the Year, 550 points to 300 points over runner-up Dick Hughes, a right-hander who’d gone 16-6 for the world champion St. Louis Cardinals.

For Seaver, it had been a very good first year in the major leagues.

__________________________________

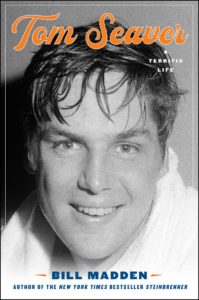

From Tom Seaver: A Terrific Life by Bill Madden. Copyright © 2020 by Bill Madden. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Bill Madden

For more than forty years Bill Madden has covered the Yankees and Major League Baseball as the national baseball columnist for the New York Daily News. He is the author of several books, including the New York Times bestseller Steinbrenner, and has collaborated on memoirs by Lou Piniella and Don Zimmer. Madden was the 2010 recipient of the Baseball Hall of Fame's J.G. Taylor Spink Award and is a member of the Writers Wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He lives in Florida.