When Sidney Poitier Went to the Moscow Film Festival

George Stevens, Jr. on Cold War Cultural Diplomacy Behind the Iron Curtain

The Cold War and the contest of ideas with the Soviet Union were high on USIA’s agenda as I made plans to lead the American delegation to the 1963 Moscow Film Festival. “I’ve agreed to serve on the jury in Moscow,” producer-director Stanley Kramer informed me in a phone call from Hollywood.

Stanley was a friend who was known for making successful films with social content. I suggested that this was an opportunity to screen American films behind the Iron Curtain. Stanley was keen on the idea, so working with a young foreign service officer in the American embassy, Terry Catherman, I put together a list of Kramer films to determine if the Russians would be receptive.

With surprising speed they indicated a willingness to host showings of Judgment at Nuremberg, Inherit the Wind and The Defiant Ones at the Moscow Filmmakers’ Union, and invite Kramer to speak. I knew Stanley would effectively represent an American point of view.

Word came that the State Department had concluded that the proposed films were “not appropriate.” They thought The Defiant Ones, with Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis as clashing chain gang prisoners, would confirm the Soviet line that the United States was a racist country, and Judgment at Nuremberg would undercut our ally West Germany by reminding viewers of Nazi atrocities.

Bureaucratic tussles escalate quickly and views harden, so I reached out to a new acquaintance, Averell Harriman, a senior figure in Kennedy’s State Department. Averell had served as governor of New York and was our ambassador in Moscow during the war, attending the Yalta Conference with Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin. Now in his seventies, he understood the levers of power.

His mental agility and tough-mindedness led colleagues to call him “the Crocodile.” (“He just lies up there on the riverbank, his eyes half closed, looking sleepy. Then, whap, he bites.”) I made my case about Kramer and the kind of films we wanted to screen, and was heartened that he shared my view.

Harriman called me at home at seven the next morning. (I later quizzed him about these early calls. “I like to get people thinking about my issues before they get busy thinking about their own.”) “Your problem is Tommy Thompson,” he said. “I’ll arrange for you to see him.”

It occurred to me that if we could get Sidney Poitier to come to Moscow, his charismatic presence would cast a positive light on the public screening

Llewellyn E. Thompson, twice American ambassador in Moscow, was now Kennedy’s ambassador-at-large serving on the National Security Council, advising the president on Soviet affairs. I felt like a Hollywood rookie when I got off the elevator on the seventh floor, where power resided at the State Department.

Ambassador Thompson was cool but courteous, and seemed prepared for a serious discussion. He listened while I explained my view that Soviet filmmakers whose creativity was constrained by the state would respect these films and envy the freedom of Americans to address controversial issues. The ambassador surprised me by reversing himself and approving the showings, with the caveat that Kramer’s films be shown only to the film community, not the general public.

Terry Catherman met me at Sheremetyevo Airport on a gray July day and took me to the Hotel Moskva. He was working on preparations for Harriman’s test ban negotiations but was excited by his concurrent duties with our delegation. Moscow was drab and grim and inhospitable to tourists, even in midsummer. We would soon be referring to the Moskva—a massive gray neo-Stalinist building near the Kremlin with a lobby that resembled a train station—as the Comrade Hilton.

There were delegations from sixty-four countries, including Soviet client states North Vietnam, Cuba and East Germany, which gave the festival a political aspect not seen at Cannes or Venice. Minister of Culture Yekaterina Furtseva, who worked her way up from being a weaver in a textile factory to the first woman to sit on the powerful Presidium, was on hand. There was a saying: “Whatever Khrushchev thinks, Furtseva says.” She dressed with more style than was customary for Soviet women and was especially hospitable to the glamorous, left-leaning Simone Signoret and her husband Yves Montand, and to Federico Fellini, who arrived with his wife Giulietta Masina and his new film, 8 1/2.

But when it was time to negotiate, Furtseva displayed the steel of a party apparatchik. Her deputy, Vladimir Baskakov, a towering man with a static eye that gave him a menacing look, controlled the festival. A Russian friend warned that Baskakov was a nasty piece of work.

The opening ceremony was in the newly constructed Palace of Congresses inside the Kremlin, the six-thousand-seat auditorium with marble columns where major political events took place. Senior officials and astronauts were seated on the stage decorated with flags of participating nations. To our surprise Stanley Kramer received an ovation when the jurors were introduced. Later when his films were screened the audience chanted, “Krah-mer, Krah-mer.”

I explained my view that Soviet filmmakers whose creativity was constrained by the state would respect these films and envy the freedom of Americans to address controversial issues.

Our delegation also included Danny Kaye, Geraldine Page, Shelley Winters, composer Elmer Bernstein, screenwriter Abby Mann, and Ilya Lopert, a Lithuanian-born American who was head of United Artists in Europe. Ilya, clever and tough and able to swear in seven languages, became my counselor and good friend.

“Hollywood—A Hit in Moscow!” was the banner headline in Variety. “Hollywood,” wrote correspondent Harold Meyers, “has accomplished a major breakthrough at the Moscow Film Festival in striking contrast to its participation in previous years.”

So far, so good.

Minister Baskakov saw the response to the Kramer films and surprised us by announcing—contrary to my agreement with Ambassador Thompson—a Sunday evening public showing of The Defiant Ones in the Palace of Congresses. I went to see Baskakov and took Ilya Lopert with me. “Vladimir,” I said, “our agreement is that the Kramer films are to be shown only at the Filmmakers Union.” Baskakov was obdurate. He had the film and he was going to show it on Sunday, demonstrating that in the Soviet Union possession is 100 percent of the law.

Ilya and I retreated to my suite. I was distressed about violating my understanding with Ambassador Thompson, but it occurred to me that if we could get Sidney Poitier to come to Moscow, his charismatic presence would cast a positive light on the public screening. Ilya and I grappled with the maddening Soviet phone system, and three hours later connected with Sidney, who was filming in London. I told him about the screening in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses.

“Sidney, your presence would make it a great night for America in Moscow. Ilya can arrange with United Artists for you to get Saturday off. Will you come?”

“I’ll be there,” Sidney said after a pause. “I’ll get my own ticket.”

On Saturday afternoon Ilya, Terry Catherman and I were about to go meet Sidney’s flight at Sheremetyevo when the phone rang in my suite. It was Baskakov. “Mr. Stevens. Kremlin Palace no longer is available. The Defiant Ones now is at Palace of Sport on Sunday morning.” Shell-shocked, I looked up from the phone. Ilya grabbed it and began cursing Baskakov in several languages. We now faced telling Sidney that the prestigious Kremlin Palace screening was now taking place outside of town on Sunday morning.

Sidney, gentleman that he is, accepted the news gracefully and Stanley Kramer joined us for dinner at Aragvi, a Georgian restaurant favored by the cultural elite (we called it Sardi’s Very East). We had a vodka-laced dinner, joked about Soviet duplicity, and returned to the Moskva for an early morning pickup.

We saw a serpentine line of eight thousand Russians standing in the morning chill. They were waiting to see the American film.

The American delegation had a major asset in our assigned interpreter Vladimir Posner. In his mid-twenties, Vlad had gone to Stuyvesant High School in New York until his father, a Russian-born film executive, was charged as a spy and returned to Moscow. Vladimir’s English had a New York patina, and his fluent Russian made our translated remarks accessible and our events enjoyable. (Two decades later he would become a prominent Soviet affairs commentator on ABC’s Nightline.)

Vlad joined Sidney, Stanley, Ilya and Susan Strasberg, who was on our delegation, in a van for the Sunday morning ride to the sports arena. We turned off the highway, circled the parking area, and approached a vast wooden building—at which point we saw a serpentine line of eight thousand Russians standing in the morning chill. They were waiting to see the American film.

We took the stage and I spoke of the freedom we enjoyed in the United States. “I’m glad so many of you can see The Defiant Ones, a film that explores tensions in our society.” Vlad translated my words, then Kramer’s. “This film deals with some of our faults and it reaches out to you for your understanding,” he said to applause. “We hope one day you will be able to explore issues in your own country that concern you.” Sidney, dignified and magnetic, said, “I live my life as an actor and relish the opportunity to play challenging roles.” The lights went down and The Defiant Ones unspooled.

Tony Curtis, a surly chain gang prisoner shackled to fellow inmate Poitier as they try to escape, says, “You know the trouble with us? We spend all of our life not saying a word—we wait until we die before we shout.” This evoked a spontaneous ovation.

At the climax, their chains broken, the two men run to leap on a moving train. Sidney hoists himself up. He extends his hand and Curtis clasps it. Poitier struggles to pull him aboard. The audience began applauding, only to see both tumble from the speeding train and be recaptured.

Henry Tanner’s report in the New York Times described the Russian spectators jumping to their feet. “In an extraordinary display of emotion almost the entire audience began streaming toward the corner of the huge hall where Sidney Poitier, the Negro star of The Defiant Ones, was standing. There were mostly young persons. Many wiped tears from their eyes as others cheered and clapped.” I saw Sidney look down and observe how moved Susan Strasberg was, and watched as he drew her to her feet, her sunglasses falling, revealing tears as she wept openly. Sidney embraced her and the roar of the crowd strengthened.

Tanner observed in the Times, “The young Soviet artists and intellectuals who are struggling for greater freedom of expression have reason to be gratified by what happened here during the Moscow’s Third International Film Festival.”

___________________________________

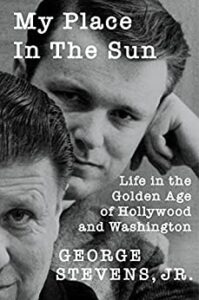

Excerpted from My Place In The Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington by George Stevens, Jr. Copyright © 2022. Available from University Press of Kentucky.

Featured image: Sidney Poitier expresses appreciation to interpreter Vladimir Posner on return from screening of The Defiant Ones at the Sports Palace in Moscow, July 1963. Left to right: John Strasberg, Susan Strasberg, Stanley Kramer and Stevens, Jr.

George Stevens, Jr.

George Stevens, Jr. is a director, writer, producer, and playwright. He is the founder of the American Film Institute, creator of the AFI Life Achievement Award and the Kennedy Center Honors, and has served as co-chair of the President's Committee on the Arts and Humanities for President Obama. Awards and honors include fifteen Emmys, eight Writers Guild and two Peabody Awards, the Humanitas Prize, the Spirit of Anne Frank Award, an NAACP Legal Defense Fund Award, and an Honorary Academy Award in 2012. He is the author of Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood's Golden Age and the Broadway play Thurgood. Find out more at georgestevensjr.com and follow George on Twitter at @officialgsjr.