What’s a Poetry Reading Doing at a Tech Start-Up Anyway?

On MailChimp's GetLit Series, and Poetry and Advertising's Long Relationship

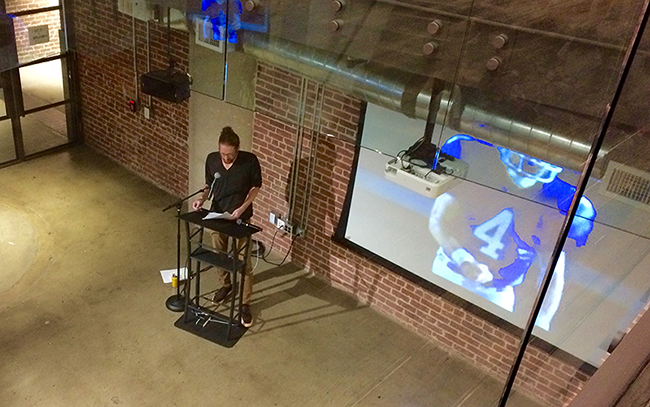

The poet Nick Sturm has given dozens of readings at coffee shops and bars and bookstores and universities and once, from inside the bathtub of a house in Akron, Ohio as a shower pounded over his shoulders and sprinkled into his can of Colt45. But it was not until a Thursday evening this September that Sturm, 31, gave a reading from inside the corporate headquarters of a tech start-up, beside a projection of its logo.

“So that’s, like, checked off the list,” Sturm quipped as he introduced his first poem to his audience: 75 employees of the Atlanta start-up MailChimp and their invited guests, who leaned forward to hear him speak from their seats in the office amphitheater, a cascade of steps that led down to the office’s lowest point where Sturm stood on raw concrete.

Photo by the author.

Photo by the author.

Founded in 2001, MailChimp provides small-business owners with a package of marketing tools that help them build, maintain, and grow their client base through email newsletters. Its employees often deploy literary language to promote a brand or spread a specific message rather than as a form of artistic expression. The company’s “Book Club” refers to a series of in-house texts that set policy. And its library is stocked with business titles such as Pre-Suasion, Brainsteering, and The Art of Deception.

But since March of this year, MailChimp has invited local writers to read to employees over local beers and beef skewers, pinot noir and guacamole.

The series, GetLit, was founded by two employees, Kory Oliver and Matt DeBenedictis who are both fixtures in the city’s literary scene, having run readings and presses and podcasts, but who, like most writers, needed better paying day jobs. Sturm knew both organizers socially, but remained wary. He had never heard of a poetry reading in an office before. “I came in kind of cynical, unsure of what this means, why I was being asked,” he said.

Sturm agreed for two reasons. The first was economic. MailChimp has branded itself as a top sponsor for Atlanta’s arts, investing $1 million of the $400 million that it reported in profits over last year to local organizations. And some of that cash goes to the city’s literary life: to the arts publication Burnaway and to the region’s biggest literary festival. For these and other efforts, MailChimp was the first corporation to win Atlanta’s Nexus Award, a prize that has in the past only gone to artists, critics, and curators.

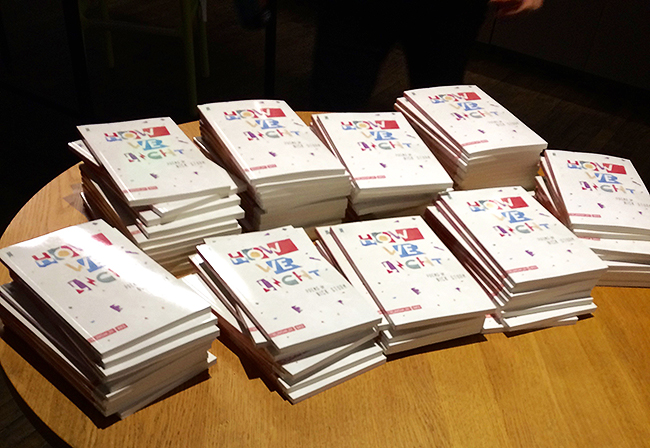

To this end, MailChimp buys 150 copies of an author’s work to distribute to employees at every GetLit reading. Sturm calculated that would bring in $1,500 to the publisher of his 2013 book, How We Light. Such numbers rarely make cameos in the sales ledgers of independent poetry presses; a sale of 150 books would nearly wipe out the poetry section at the nearest bookshop—Posman Books—which on the night of the reading stocked just 173 books of poetry by authors from John Ashbery to Kevin Young.

Photo by the author.

Photo by the author.

Sturm’s second reason to accept was artistic. Outside of his poetry, Sturm is a scholar of the second-generation of New York School poets, a group that was famously unpretentious about spaces and audiences, reading in yards and churches and community centers to crowds as small as eleven. Sturm himself founded a series at a punk bar in an Ohio basement where beer was sold for 50 cents because, like the poets he studied, he had come to believe that poetry could create an ecstatic moment in any space.

“You really want people to have an experience with the sound that you make,” he said. “It’s like music. It doesn’t matter where you play, you’re going to create a certain tone.”

*

MailChimp’s headquarters occupy the fourth and fifth floors of the Ponce City Market, the former location of a Sears, Roebuck, & Co. factory, whose industrial grommets and exposed brick have been polished by the same developers who transformed a former Nabisco factory on Manhattan’s west side into the glitzy Chelsea Market. It’s an Atlanta development that makes no secret of its outreach to millennial consumers. The building hosts an annual Millennial Mixer Holiday Party, serves up bao sandwiches and artisanal cocktails in its network of food stalls (don’t call it a food court). By the elevators that lead to MailChimp’s entrance, a booth sells canvas coin purses printed with cheeky, twitter-ready sayings including, “Someday I Hope to Respect Myself as Much as I Respect Beyoncé.”

To park downstairs for the duration of the event costs any non-employees $9. And to reach the rotunda, we gave our names to a security guard who summoned the company’s Employee Happiness Ambassador, a young woman with a helmet of dyed, purple-gray hair, who pressed a finger to a sensor against the door that, recognizing her print, clicked open the locks.

We wandered through the vast, corporate lobby, where statement art is meant to broadcast the company’s taste for whimsy. A mural proclaiming “Passion Never Fails” loomed over a reception desk, and rows of neon skateboards paneled the company board room. At the top of the amphitheater where Sturm would read, a concrete column had been wrapped with knitting to resemble the striped bark of a beech tree. A miniature zeppelin hung on wire above tin tubs, where cans of LaCroix lay out like oysters on beds of packed ice. But before a guest could reach for a seltzer, a man in a catering uniform withdrew a towel to wipe down the can. “We don’t want your hands cold,” he explained.

Photo by the author.

Photo by the author.

No bartenders had performed that service at the punk bar in Ohio. “You can’t even have an experience of physical discomfort in this place in the slightest, most meaningless way,” Sturm observed, as he munched on potato skins beside his collaborator and wife Carrie Lorig. They looked slightly out of place, too human for the air; Sturm’s thick red hair frizzed out of its bun, and Lorig’s white silk dress swished in the slight breeze of the air conditioning. But they could also have been mistaken for other MailChimp employees—thirty-somethings sitting at a table spread with a white cloth.

As employees filled the echoing space, slinging down their totes—Wythe Hotel, WNYC—slurping from cans of Dale’s Pale Ale, and pulling out iPhones, they seemed to take no notice of Sturm or his guests. Jordan Samet could not help watching the crowd from a researcher’s perspective. A PhD student in Accounting who studies the relationships between employers and employees, Samet was struck by the simple fact that employees had opted to stay at work, after work. Research has shown that company perks—from the LaCroix, to the bikes that MailChimp rents to its employees at no cost—can ultimately result in financial payouts for the company when it comes to recruitment and loyalty. “It seems ‘New-Age-y’” Samet said. “But it works.”

That relationship, which economists call Gift Exchange, does not only apply to physical rewards. Speaking to Slate for a puff piece on MailChimp’s interior decor, MailChimp’s general counsel explained how the “Passion Never Fails” mural performs a double duty: assuaging the anxiety of workers, while making them into active, if sometimes inadvertent, marketers. “The mural in our entry hallway is a particularly good example of how the murals [affect] morale and speak to people personally,” Valerie Warner Danin told Slate. “Parts of that mural end up in employees’ Instagram feeds all the time, always with a different caption or interpretation as to how that part relates to them or their day.”

The incorporation of art into the office, and the pull of poetry there alongside it, is part of a 20th-century trend. It’s management’s response to the complaints of workers and the broader culture that the office has become a space that kills that “passion” and produces generations of gray-flannel-suit wearing laborers. “For a long time corporations have been trying to restructure their workplaces in order to make them feel less like workplaces and more like art places, to allow workers to feel they’re having authentic experiences in the workplace” says Jasper Bernes, a poet and scholar who looked at that trend for his book, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization. “Now managers are asking for the same qualities that poetry provides.”

To that end, MailChimp’s in-house leadership academy, MailChimp University, was developed by an Emory University researcher who asked, “How can we have better conversations?” And the company’s style guide—written by a former Paste magazine editor turned Communications Director—sounds almost like a college course in poetry, with the title “Voice & Tone.” The guide urges employees to write in a manner that is “human,” to always aim to “speak truth,” and to “to write for and about other people in a way that’s compassionate, inclusive, and respectful.” The guide also betrays a flirty openness to the poem as form, especially when describing the brand’s voice:

MailChimp’s voice is:

Fun but not silly

Confident but not cocky

Smart but not stodgy

Informal but not sloppy

Helpful but not overbearing

Expert but not bossy

Weird but not inappropriate

But while the structure of that guide might recall poetry, the content condones a censorship of life’s negative, “sloppy” emotions and “silly” truths that would make any writer flinch.

On the evening of Sturm’s reading, employees had arranged magnetic poetry kits on the office refrigerators into the phrases: “Should you smash laptop,” “Integrate explode is you” and “human advertise marketing overthrow.”

*

The lines between corporate culture and poetry have never been as starkly drawn as some poets would have you think. The American poet James Merrill was a Merrill-Lynch Merrill; T.S. Eliot worked as a bank-clerk while concocting The Wasteland; and the poet that Nick Sturm has devoted his own scholarship to—Ted Berrigan—once quipped, “On Easter Sunday, you rise from the grave—which is great. But on Easter Monday, you have to go get a job and support yourself—which is not so great.”

W.H. Auden absconded from his job in a propaganda office to serve on the front lines in the Spanish Civil War, but ended up teaching AT&T executives in the 1950s. As poetry invaded workplaces, Marshall McLuhan observed how ad copy had become the “main channel of intellectual and artistic effort in the modern world.”

Christopher Grobe argues in “Advertisements for Themselves: Poetry, Confession, and the Arts of Publicity” (forthcoming in Cambridge Press’ American Literature in Translation 1950-1960), that it was the first New York School of poets who openly tore down poetry’s high walls to let in advertising’s vagaries, with Frank O’Hara dropping brand names into the Lunch Poems he penned during his day job at MoMA, declaring the ultimate branded American experience—“Having a Coke with You”—to be “even more fun” than visiting a litany of post-war European sites, or contemplating exhibitions of European art.

O’Hara’s work convinced the poet Max Blagg to quit his day job as a bricklayer and venture to New York, where in 1992 he followed the path his idol had carved for him. Appearing in a campaign for Gap jeans, Blagg read a poem that referred both to intimate sexual experiences and to the fit of denim “like an old lover coming back for more / curved into the shape of your thigh / like they were custom made to do just that.”

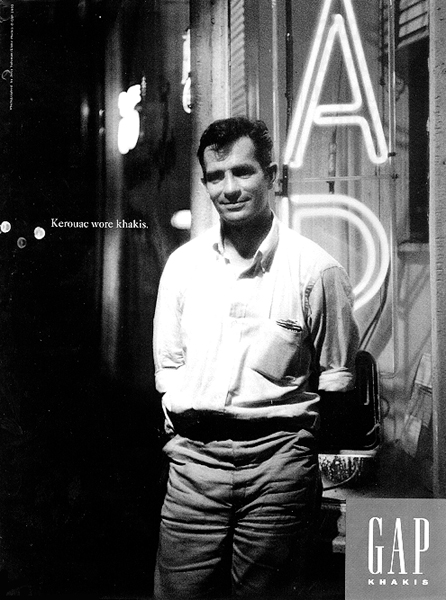

The poet Bob Holman, a founder of the Bowery Poetry Club, remembers Blagg’s television spot opening the gates for a number of collaborations between poets and corporations, including one Holman participated in with Nike. But there was also a cost to such collaborations, Holman recalled: a relinquishing of control. Holman refused to read on a tour sponsored by the cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris when the company wanted final approval of his content. And in a footnote to Joyce Johnson’s memoir of the beat years, she notes that the retailer Gap actually “airbrushed out” her image from a photo of a slouchy, care-nothing Kerouac that had been re-tooled to sell khakis.

As poets once filtered into AT&T offices, they are now wandering into the communications hubs of our day: tech spaces. The poet C.K. Williams has read from a TED Talk stage. And in 2008, when Google was in the midst of a court battle with New York’s Authors Guild over content, the poet Al Young dropped into its headquarters. The reading was part of the “Authors at Google” series, which is now streaming on YouTube. But at that reading, Young counseled other poets to be wary of giving up control to corporations. “If we leave public discourse and we leave language to the cultivation of corporations and politicians and governments it will degenerate, and it has degenerated,” Young said. “This is not real language—this is language that has been fashioned by a press secretary or someone for the purpose of covering something up or deceiving or steering people off on the wrong track.”

Some critics have judged poets harshly for wandering too far toward corporate control. Writing in Harper’s, Jonathan Dee argued that one of the poets who worked alongside Holman with Nike would only ever be known as the “poet from the Nike television commercial,” having “demonstrated that the content of her work is arbitrary; that is, it’s for sale.”

As Daniel Kane recounts in his history All Poets Welcome, the poet, who called herself Emily XYZ, countered in a letter to the editor: “Wrong! I am just as obscure as ever, only I’m a little less in debt.”

For Sturm and the poets of his generation, debt feels much more immediate than the idea of a sacrosanct space where poetry lives without interference from corporations. Sturm holds a PhD in poetry, has been featured in the Best American Non-Required Reading, and has scraped by thanks to day jobs delivering pizzas, working in a skate shop and at a driving range, managing a campus convenience store, and toiling on a corn farm. Even now as he teaches writing to college students, Sturm helps to pay the bills by working as a proofreader and a critic.

To Sturm, university spaces feel no more open to the experience of poetry than punk bars or corporate offices. Sometimes, those spaces may actually be less open, he says. “If you go into a university and you’re reading, all these grad students and undergrads and faculty, they all have these preconceptions about what poetry is and what it does,” Sturm said. “Maybe you said one thing about Kristeva in a poem, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, that Kristeva reference. Let me tell you about my Kristeva thing.’”

But at MailChimp, no one drew Sturm aside to impose their own readings over his work. “We were equals,” Sturm observed. “And when you find people ready to experience a certain sound because their expectations haven’t been tamed by a particular narrative, then that’s really—that’s really exciting.”

“For Sturm and the poets of his generation, debt feels much more immediate than the idea of a sacrosanct space where poetry lives without interference from corporations.”

MailChimp seems uniquely open to the work of poets. Writing in The Guardian last year, Lara Williams claimed that MailChimp’s platform, TinyLetter, could be the “saviour of modern poetry,” as hundreds of poets use the platform not just to distribute news about events to fans, but also to distribute poems directly to readers, short-circuiting publishers all-together. Michael La Ronn’s self-help guide for poets, Indie Poet Rock Star, recommends using MailChimp to keep readers informed, while Poets and Writers magazine maintains five separate email newsletters for its readers, and the publisher McSweeney’s uses the platform to sell its books. Even Jasper Bernes says he uses the platform for the small press he helps run, Commune Editions. And here’s why. As the writer Zan Romanoff reports, she receives more and deeper feedback from her 600 subscribers on MailChimp’s TinyLetter platform, than from the more than twice as many who follow her on Twitter. “Being allowed into someone’s email feels intimate,” she says.

It’s that intimacy that prompted Lyz Lenz, writing in the New York Magazine blog The Cut, to compare TinyLetter to the “secret script used by women in the rural villages of Jiangyong in Hunan Province of China.” That 2015 article ran below the headline “Are Newsletters the Internet’s New Safe Space for Women?,” and quoted a female writer who had moved her work from a blog to TinyLetter, after what the writer called an “overwhelming” negative response to a post she wrote about a film’s depiction of a rape.

But intimate audiences have a cost.

*

When I reached out to MailChimp to speak to the founders of its reading series about these and other questions, a public relations employee barred an interview, and demurred from fully answering one question with the line, “We like secrets almost as much as we like readings.”

For weeks, the line needled me. I thought of it while speaking over the phone to my mother, and fending off a colleague from reading my emails. It quickly became my favorite excuse to keep something hidden. At the same time, it reminded me of just what seemed strange about a poetry reading in a locked and gilded room. So when I ran into the GetLit founder Kory Oliver at a bar weeks after the reading, I mentioned that I was still bothered by the cutsey line and Oliver, like any writer proud of his creation, blurted out, “I wrote that.”

So I was surprised to see Oliver go public on November 1st. In a blog post on the company’s website about the series, he opened with MailChimp’s mission statement: “to make Atlanta ‘better, weirder and more human.’” And he described how coworkers said they felt “motivated” to explore “other literary events” as evidence that the series accomplished that goal, creating an “impact that continued to reverberate.”

A reverberation is a low, growling noise felt in the heart and the lungs. Merriam-Webster defines it as to “continue in or as if in a series of echoes.” And I wondered why Oliver was praising poetry that created such a quiet sound rather than a scream. To me, the aims of poetry—any poetry—feel at odds with a lack of transparency. How can poetry be powerful if it isn’t allowed to permeate through the culture? Or, as a poet might put it, what is the point of baring your soul in private?

*

MailChimp’s Austin Ray, 34, toggles between a day job and a life as a writer. In addition to working as a content editor, crafting in-house brochures and announcements, Ray writes on culture for such publications as GQ and Rolling Stone. He took the podium to open the September GetLit reading with a work of experimental, essayistic prose.

“I’ve come to believe that tweeting about chard is, perhaps, the only thing that will save us as a human species,” Ray said, tongue halfway in cheek. “While the world is often a difficult, angry and hopeless place, chard provides. Take some reassurance from that and tweet about it.” The piece lived in the middle kingdom between apostrophe and instructional, taking on the tone of blogs for clients and employees that Ray regularly authors. Organizer Matt De DeBenedictis pointed out the pattern, joking as he took the podium that the piece could have been titled, “Developing Your Chard Brand.” The audience laughed at that—a reaction that proved a challenge for the next reader, Nikki Ferron, a new hire in the company’s compliance department.

Ferron warned the audience that her poem “might give you the feels.” And in quite a different tone than one could imagine Ferron pointing out a problem of compliance, she said, half spitting, her enormous voice turning the concrete room into a theater, an opera house: “Can someone please explain / why the solution to a problem is always a war / that creates infinite problems / that hurt us even more?” Her poem strummed through quick rhythms to hit dark, emotional notes.

When it was finally Sturm’s turn to take the stage, the room was boiling over emotionally, ready to be moved by the poet that stood before them in muted tones—brown corduroys, brown sneakers, and a washed out greenish sweater.

Sturm announced that he would read his poem “A Basic Guide to Decision Making” in part because it includes reference to a power point presentation. Then he took a step back. “But I don’t know if you guys have power points. I love how I need to ask that.”

The poem is hardly about a power point presentation, or a diet coke can, or origami swans, or any of the other 21st-century detritus that, like O’Hara’s can of coca cola, helps to gird the poem’s structure. It walks us through a magical-realist fable of a town that gives up on the dreams of its forefathers, beginning with a gathering much like the one in MailChimp’s own halls, where a civilization meets to “discuss the issue” of building a bridge. In the meeting they become distracted, fall asleep and “When the people at the town meeting / woke up they tried to remember the PowerPoint but the past / was like a bleached coral reef . . . ” Rather than following their original mission, the townspeople start afresh, establishing a new town in the place of their meeting, and “After a few generations . . . ” their heirs forget what they had come for, what truths they had been searching. They’re brought back to the mystery of their past when “In a pile of rubble, someone found a Diet Coke.” And so another meeting begins, which finds the townspeople deciding to do exactly what their forefathers had wanted them to do: “They did not know why they chose to build a bridge / only that the idea to build a bridge felt good . . . ”

And much like the people in the town who did not know why they were building a bridge, the people in Sturm’s audience might not have known why they were listening to poems—that ancient art form, that message from their forefathers—in the offices of a start-up. But it had begun to feel good.

Sturm’s final poem, “Endzone,” is a meditation on male chauvinism, group-mentality, and physical combat as told over clips from the 1999 film Varsity Blues. The film is about a football team that overcomes steroid use to triumph over a rival school or, as Sturm puts it in his poem, a “Clash of Kings, as though that’s actually a conflict / One side gets more points, but the structure is intact.” The poem is an ode to Guillaume Apollinaire’s “Zone,” which describes the soullessness of Europe’s baubles on the eve of the first World War, and like that poem, Sturm says in his lines, it also “produces a portrait of a failing culture on the cusp of change.”

But before Sturm began to read his own work, he hit play on a recording of Ted Berrigan talking about his experience playing football. The room filled with the dead poet’s gravelly, time-scraped voice. And for a moment, as if in automatic reaction, the audience looked away from Sturm and around the room. They were hunting for the source of the sound, looking for the speaker. But he was not there. And as they looked around they looked at each other, smiled awkwardly, waved hello. In their quest for an absent poet, they had locked eyes only with each other.