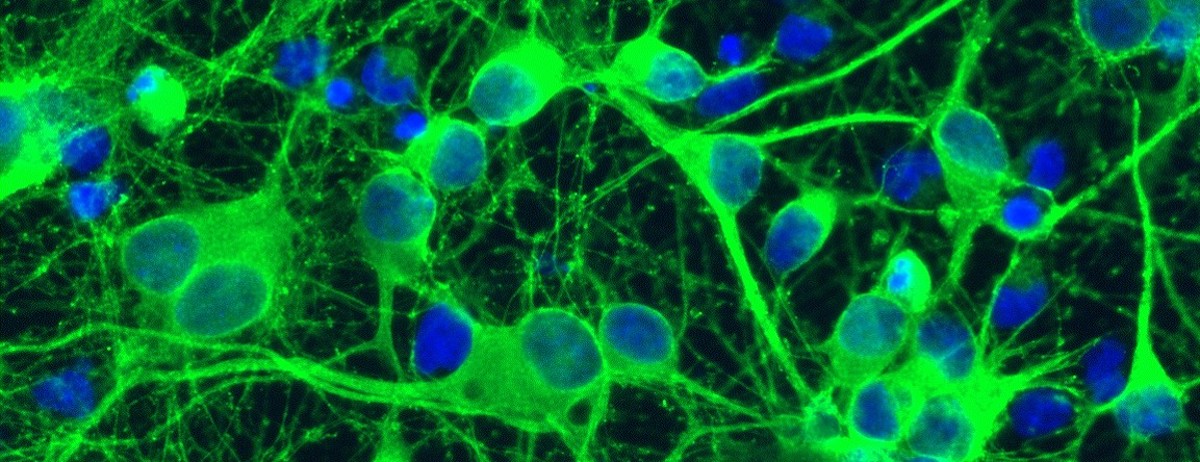

Dori Schafer—the “scientific daughter” of Beth Stevens and “scientific granddaughter” of Ben Barres—is a dedicated, down-to-earth researcher who, ten years after bursting onto the scientific scene as a young investigator in Stevens’s lab and pioneering the imaging technique that demonstrates how microglia destroy synapses, is now an award-winning scientist in her own right. Schafer serves as a professor of neurobiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, where she continues to study the role of microglia in an array of diseases across the life span.

I turn to Schafer—the first scientist ever to observe microglia destroying synapses in real time under her microscope—and ask whether she thinks the emerging science on microglia gives us new insight into the increasing number of neuropsychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders we’re seeing in so many different age groups.

Schafer agrees it’s a crucial question for our time, and one that scientists are only now beginning to ask. “We’re just scratching the surface as to the environmental effects of our modern environment on brain health,” she admits. “And once we ask that question, we have to also ask how today’s environment is affecting microglia” in specific. Is something in our environment triggering these tiny cells to express more inflammatory factors, and potentially eat more synapses—resulting in more disease?

“Microglia have always been around, even if we are just starting to understand their role in brain health,” she explains. “So that hasn’t changed.”

Genetics, of course, plays a role in which individuals are more prone to develop a certain disease at a certain time in their lives. Whatever genes made it more likely that Heather would grow up to develop dysthymia made it more likely that her daughter, Jane, would face anxiety too. But it is also true that there are no genetic epidemics. Genes simply don’t change that fast, over the course of a generation. Genetics alone cannot account for these growing trends.

To some degree, Schafer points out, higher diagnosis rates are also at play—more primary care providers are trained to catch psychiatric disorders and addiction in patients and intervene as early as possible, and more pediatricians are on alert for neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders in children and teens. And, as more Americans are aging, public health efforts have educated us about Alzheimer’s—so more aging Americans are getting diagnosed sooner.

When you are sick, microglia crank up inflammation so that you don’t feel like engaging with life.But better diagnosis rates can’t account for these staggering trends. So, if microglia haven’t changed, and there are no genetic epidemics, and better diagnosis rates alone don’t account for these rising rates, what does?

“Our environment has changed a great deal in such a very short period of time,” says Schafer, who has a wide, open smile and shoulder-length ash-blond hair. “We’ve undergone enormous changes in our diet in the past hundred years, we’ve been exposed to more toxic chemicals in the environment—and there are just so many more chronic societal stressors in everyday life.” For instance, she says, “We know that kids growing up, especially girls, are exposed to a lot of psychological pressures in our culture that are novel.”

For instance, Schafer points out, “Growing up as young women, we receive constant cues regarding body image and gender roles. We are also continuously on guard, witnessing sexual harassment at school and in the workplace and seeing how women are depicted in the media.” Girls can’t help but worry, at every turn, whether they measure up—and whether they are safe in our society.f

Given the ubiquitous nature of social media in today’s digital age, most girls are exposed to these chronic psychosocial stressors—a never-ending stream of stories about incidents of violence or inequities perpetrated against women, as well as commentaries critiquing images of the female body—on a relatively constant basis. And, often, girls manage any stress they may feel alone—in today’s society, we frequently lack the kind of wider community connectedness and extended-family closeness that can help buffer the effects of stress.

“And we know that chronic stress changes the body and brain,” adds Schafer.

All of these toxic exposures, Schafer says, “result in peripheral immune events that affect the brain and vice versa. The interesting thing is that when these events affect the brain, they affect microglia too.”

Part of the problem in elucidating this trend is that “it’s hard to nail down any single environmental event,” she says. Instead, myriad triggers—exposure to environmental chemicals, unhealthy diets, chronic stressors—add up, affecting the brain’s microglial immune response in a cumulative way, which could lead to more runaway inflammation and more synapse loss over time.

We also know that microglia communicate with the body’s immune cells. And we know that microglia can be easily triggered to spark neuro-inflammation, or chip away at brain synapses, by the very same stimuli that elicit inflammation in the body.

So why have microglia, which should function as the protective immune cells of the brain, morphed so dramatically in so many individuals from behaving as the angels of the brain into dangerous assassin cells in the course of just a few generations? Well, that requires a brief trip back in time.

Let’s pretend that it’s five hundred years ago, circa 1500, and you live in a small feudal village somewhere in Europe, where infectious diseases such as whooping cough, measles, and tuberculosis (which once had a 50 percent mortality rate) regularly make their way through your town. Many children do not survive to adulthood.

If tuberculosis starts to wend its way through your village, and you are unlucky enough to catch it, your immune system will immediately crank up inflammatory infection-fighting immune cells to do battle against the pathogen. Levels of inflammatory cytokines in your body will skyrocket. It probably won’t surprise you at this point to learn that, while you are ill, your microglial cells are also mounting an inflammatory response in your brain.

And here’s where it gets really interesting. Evolutionary biologists believe that microglial cells have a very specific and important—and helpful—reason for mounting an immune attack on the brain whenever the body falls ill. (And it isn’t to fight the pathogen or virus per se—physical infections send immune signals to alert the brain, which in turn promotes neural inflammation, but the infection itself doesn’t cross into your brain tissue.)

Microglial cells, it turns out, developed the ability to mount an immune offensive in the brain in order to help you heal, and to keep you and your family safe.

Let’s go back to our tuberculosis-in-the-village analogy. Let’s say you are one of the lucky few, and you slowly begin to recover from tuberculosis. You are still convalescing, but there are promising signs that you are turning the corner. You are going to live. Even as you continue to physically improve, however, you still feel horrendous. You feel a torpor-like fatigue, despair. You have impaired psychomotor function (it’s hard to move, or lift your arm to brush your hair). You feel a nameless dread and malaise you can’t shake. You want to curl up into a little ball and keep the covers over your head and rest, for what feels, at that moment, like the rest of your life. And that’s because, even as your body begins to successfully battle the infection, microglia continue to spew forth inflammatory chemicals in your brain, causing changes to neurocircuitry that change your behavior too, in ways that will likely prompt you to experience a complete loss of interest in life—or anhedonia.

In other words, in addition to the physical symptoms that accompany tuberculosis, you are now also exhibiting what physicians call “sickness behavior.” Even as your body continues to improve, your brain feels groggy. You still feel too tired to get up and wash your face, to dress yourself. You feel depressed, unmotivated, fatigued, and sleepy, and find it hard to concentrate.

So you mostly keep to your bed.

And the reason you feel so depressed and unmotivated is, once again, thanks to microglia. When you are sick, microglia crank up inflammation so that you don’t feel like engaging with life.

Many of these 21st-century triggers can cause our inflammatory response to go on high alert—poised for an all-out defense.And that, it turns out, is a pretty neat evolutionary trick.

Even as you start to recover, you still don’t feel like moving, socializing, or engaging in activities that used to interest you. And that means that your immune system can leverage all of the body’s resources for healing. With this more robust immune response, you get better faster. This also helps your kin: By staying in bed, you’re less likely to spread your germs around. So your children and siblings and cousins are more likely to survive too, which allows them to pass the genes you all share along to the next generation. Your social withdrawal also minimizes the likelihood of your being exposed to additional infectious agents in the world outside.

By the time you feel clear-headed and well enough—mentally and physically—to go back to your normal day-to-day life of helping with the harvest, or selling market wares, you no longer need to conserve all of your energy for healing.

If you’re a child and you survive, you get to grow up, have children, and pass your heartier immune response to this pathogen along to them, which will help them survive in the future.

Just a short period of microglia-enhanced depression, aka “sickness behavior,” could save your life, and the lives of your family.

This is, as we all know, a classic tale of natural selection.

But what’s entirely new is the recognition, among neuroimmunologists, not only that our immune systems evolved alongside microbes and pathogens, but that this coevolution conferred some benefit to our ancestors because of the fine-tuned glial immune response in the brain, which influenced our social behavior in profound ways.

Our ancestors’ immune systems became “highly educated” to respond in smart social ways to a pathogen-rich environment. And it is microglia that gave us much of our evolutionary advantage in what was once a highly microbial and pathogenic world.

Meanwhile, in our twenty-first-century urban and suburban settings, we don’t face as many threats from pathogens. Infections like tuberculosis are rare. (And, as of this writing, happily, we seem to be keeping a lid on plagues and pandemics.) We live in a much more sterile environment in general too. We don’t meet up with the same microbes we once did: We don’t sleep on dirt floors, or dig root vegetables from microbe-rich soil very often (even if you do grow your own vegetables, the quality of today’s soil, for a host of environmental reasons, is more sterile than ever before).

Some of this is good news, and some of this is not such good news for us. Many of the evolutionary microbes that evolved alongside us in our natural environment kept our immune response busy and active in healthy ways too.

*

We may be living in a world that’s no longer rife with old familiar pathogens, but that doesn’t mean that we’re living in an environment that’s “too clean.”

In today’s world, our immune system isn’t encountering the accustomed nature-made pathogens, microbes, and invaders our ancestors came to know. But at the same time, we’re inundated with new and completely unrecognizable man-made foreign invaders. And these are bombarding us from every direction. Which means we’re living amid a very different backdrop of potential “threats” compared to those we evolved with. We’re coexisting amid a chemical soup of manufactured environmental toxins: eighty thousand chemicals that have never been tested on the human immune system, much less on the brain’s immune system. Nevertheless, all these chemicals are EPA-approved for use in items we come into contact with every day: flame retardants in furniture and carpets, dioxins in car exhaust, endocrine disrupters in cosmetics, plasticizers in baby toys, and toxic pesticides sprayed on our home gardens, farm crops, and agriculture, to name a few.

It’s not just the air we breathe or what we slather on our skin that’s problematic. Our diets have changed. Compared to our ancestors, we’re ingesting a fair amount of processed foods full of additives, preservatives, and other artificial ingredients that may further confuse our immune system.

And many of these twenty-first-century triggers can cause our inflammatory response to go on high alert—poised for an all-out defense.

To use our villager analogy, it’s as if your village was accustomed to ongoing skirmishes between your village and nearby warring fiefdoms. You and your comrades knew exactly how to respond to those factions.

Only now, suddenly, you’re getting attacked by a new style of warfare—bombs and tanks you aren’t prepared to defend against—from every direction.

Your immune system simply can’t keep up with it all.

__________________________________

From The Angel and the Assassin by Donna Jackson Nakazawa. Used with the permission of Ballantine Books. Copyright © 2020 by Donna Jackson Nakazawa.