“We Get to Be Young Only Once.” On My Life-Changing Discovery of Laurie Colwin

How Kim Fay Read—and Ate—Her Way Through Home Cooking During Her Formative Years

When I first read Laurie Colwin’s Home Cooking, I was a few years out of college. Highlights in my culinary repertoire up to that point included Kraft macaroni and cheese and Rice-a-Roni. I did not, as Colwin did when she started out on her own, live in a Greenwich Village apartment the size of a placemat with no kitchen.

I lived in Seattle and worked at a bookstore across town in Pioneer Square. The Elliott Bay Book Company was arguably the best bookstore in the country, with high brick walls, raw wood shelves, and a bounty of nooks and crannies in cavernous, historic rooms that once housed, at various points in time, a hotel, a saloon, a lady barber shop, and typewriter and Studebaker retailers. It was an indie bookstore, although we didn’t use that term in the early 1990s because nearly all bookstores then were independent.

Ironically, I was in charge of the cookbook section. Moi, the Rice-a-Roni connoisseur. I adored this section with a passion that belied my culinary ignorance. And it was there where I discovered that Laurie Colwin, the author of one of my favorite novels, Happy All the Time, also wrote a book of food essays. I had never heard of “food essays.” I used my employee discount on a hardcover of Home Cooking because I wanted to know more.

I took my newly purchased copy back home. My apartment was cozy, decorated with hand-me down furnishings and framed prints from my post-college backpacking trip through Europe. It was mine and mine alone. No parents, no roommates. Instead, there were two small bookshelves that welcomed my growing collection of British women novelists, and a stereo, where I listened one night, entranced, to a BBC broadcast of A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf.

I discovered that I did not have to make a choice to be this or that, sacrifice one version of me to be another version of me.

Laurie Colwin was raised by a mom who cooked with some degree of expertise. I was raised by a mom who barrel-raced horses and had to be taught by my dad, when they were first married, how to boil water. This was because, further back, she was raised by her dad, a sailor, who nourished her with tons of love and Swanson TV dinners. Though I had a cupboard full of canned and boxed foods—I could whip up Jiffy apple cinnamon muffin mix like nobody’s business—I had dreams of being sophisticated, an aspiration fed by 1950s Harlequin romances, Mary Tyler Moore, and an April 24, 1971 copy of the New Yorker that I somehow acquired during my childhood. I believed sophistication was tucked away somewhere in my genes.

With dense Seattle clouds hovering above my skylights, I curled up on my love seat—the apartment did not have space for a full-size sofa—and devoured Home Cooking in a single gulp. It was a thrill to discover that Colwin, who knew about things like polenta (never heard of it) and olive oil (never heard of that either), also loved hunkering down at home and cooking a good beef stew. Beef stew was something else I could make, along with meatloaf and peanut butter cookies using a Betty Crocker cake mix.

For those few enchanted hours, I read about a young woman who threw Manhattan dinner parties (intimidating) but wasn’t afraid to serve chili and potato salad to her guests on a fold-out card table with cigarette burns in its leatherette surface (I could do that). She wrote breezy but not fluffy novels, bought her kitchen gadgets second-hand at tag sales, disgraced herself at parties, bemoaned glamorous dishes in glossy magazines, volunteered at a shelter for homeless women, stood firm by even her most egregious culinary mistakes (gray steak cubes in lukewarm fondue), attended literary festivals, and wrote, “I love to eat out, but even more, I love to eat in.”

My world changed from that day forward. I discovered that I did not have to make a choice to be this or that, sacrifice one version of me to be another version of me. I could be many versions, from down home all the way to biggish city, at the same time. I had never been one of those small town kids who dreamed of growing up and discarding her past. I loved my past. But I wanted something more. Not bigger (after all, an Eastern Washington landscape is cinematically sweeping). Not better (I didn’t think in terms of better or worse). But varied, more suited to who I was inside. Laurie Colwin introduced me to an example of how that was possible, and she gave me the tools to begin: her recipes.

Armed with tea that I resourcefully mail-ordered from specialty shops in Vancouver, B.C. and Amsterdam, I decided that my first effort at homey sophistication would be bread. Learning to bake one’s own bread seemed like a worldly thing to do.

We get to be young only once. We get to search for ourselves in a certain kind of way only once.

What my elfin kitchen lacked in space, it made up for in newness and layout. It had a decent-sized counter perfect for kneading dough. In this space, sometimes to the rambunctious rock music of live bands at the Eagles Hall on the other side of my brick wall, sometimes to the newly discovered mysteries of Miles Davis’s Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, I mastered the bread recipe in Home Cooking—sometimes.

Other times I mastered doorstops. And at the bookstore I became known as the Laurie Colwin fanatic. My adulation was no secret. It was either charming or annoying, depending on who I was speaking to. My regular customers knew of my passion, and there was one, a young lawyer, who came in late at night, and we would pass hours trading glowing praise of our kitchen deities: his was M.F.K. Fisher.

One evening in 1992, the store’s buyer asked me to come upstairs with him to the receiving department. He was a shaggy-haired man who I rarely spoke to. Despite his self-effacing nature, he was famous throughout the country for his taste in books. Authors came to speak at our bookstore solely because of him. When we got upstairs, he let me know in his shy way that Laurie Colwin had died. At 48. Of a heart attack. He told me to take my time and left me alone, surrounded by unopened boxes, shelves of unlabeled books, trays of invoices, and October air steeped in the chill of nearby Elliott Bay. I grieved. I still grieve. We get to be young only once. We get to search for ourselves in a certain kind of way only once.

The following year, Laurie Colwin’s More Home Cooking was published. I consumed it as I had Home Cooking, in one voracious sitting, but my eagerness was mixed with melancholy. During the past months, my cupboards had become a tribute to her influence on my life, the cans replaced by spices and interesting grains. When I finished reading, I cooked and baked with new intensity. I owed Laurie that. Without a single fleck of conceit, she had taken the lead and shown me a way to be. She had given me a version of myself that felt right. I perfected her shortbread, and it became a staple Christmas present. My sister’s best friend, who also died too young, used to beg me to make it for her. She would freeze it and ration it out until the next batch arrived. I perfected her tomato pie and served it to friends for more lunches than I can count.

Tomato pie requires planning and prepping, which I did with a proper convert’s zeal. It is luxuriant with old-fashioned, non-dietary ingredients: buttermilk, mayonnaise, grated cheddar cheese. It is on page 111 of More Home Cooking. In my copy, the corner of that page is turned down (something I usually frown upon), and the page is warped from the countless times I spilled on it while cooking. I have circled the entire recipe in green highlighter, and written “Yum!” beside it not once, but twice: once in regular pen and a second time, in giant letters in pink highlighter. I served this dish to my parents when they came to visit their city mouse bookseller daughter in her brick-walled loft apartment in Seattle. I served it to one of my fellow booksellers, Beth, when we were in the courtship phase of what was to become a best friendship.

Most of all, I served it to myself. To be eaten at the small drop-leaf table beneath my skylights, while I read Margaret Drabble, Penelope Lively, Muriel Spark, Anita Brookner, and Iris Murdoch, all for the very first time. Each of them opening up a new way of looking at the world. Each of them opening up a new way to be the me I was alongside the me I wanted to be. Each of them setting out a path, the way Laurie Colwin had set out a path. She was the first writer to do so for me, and while not the last, she is the one who holds a special place in my heart. And, of course, in my stomach, too.

______________________________________________________

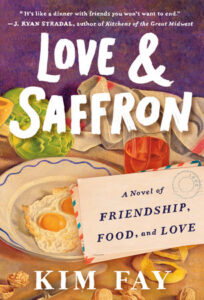

Love and Saffron: A Novel of Friendship, Food, and Love by Kim Fay is available now from G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Kim Fay

Born in Seattle and raised throughout the Pacific Northwest, Kim Fay lived in Vietnam for four years and still travels to Southeast Asia frequently. A former bookseller, she is the author of Communion: A Culinary Journey Through Vietnam, winner of the World Gourmand Cookbook Awards’ Best Asian Cuisine Book in the United States, and The Map of Lost Memories, an Edgar Award finalist for Best First Novel. She is also the creator/editor of a series of guidebooks on Southeast Asia. Fay now lives in Los Angeles.