Was Yeats' "The Second Coming" Really About Donald Trump?

How Poetry Transcends Political Crises Through Time

For almost 50 years, I’ve read and written poetry as a kind of spiritual discipline, drawn to the possibilities for alert expressiveness and concision, looking for a language that pushes into areas of thought and feeling where the undisciplined and frequently harsh discourse of everyday life—the chatter of daily conversation, radio and television, newsprint, endless commentary—doesn’t easily wedge itself. And the relevance of poetry is never at issue for me, even in this age of e-readers and blogging.

As Ezra Pound famously said, poetry is “news that stays news.” To make this point, I recently read the opening stanza of Yeats’ “The Second Coming” to a class, chanting the lines (as Yeats would have), savoring the muscularity of its phrasing, its challenge to the reader on so many levels:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre,

The falcon cannot hear the falconer.

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loose upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of a passionate intensity.

I asked the class to imagine the circumstances of this stanza, and one fellow quipped, “He’s writing about Donald Trump, right?”

He wasn’t wrong. The worst, as always, are full of a passionate intensity. Nothing changes there. But Yeats was, indeed, writing about another time of political and moral crisis. Millions had died in the Great War, which had just stuttered to an inconclusive halt, and the air tingled with fear: things had truly fallen apart. The comforting ceremonies of religion and politics, or middle-class social life, were pulled out from under the people, unbalancing them on the “blood-dimmed tide.” In Ireland, the promises of independence from Britain held as much terror as hope. “Mere anarchy” loomed, and fascist dictators on the Continent would soon capitalize on the anxieties of populations who craved certainty in uncertain times. Some “rough beast,” as Yeats suggests at the end of his poem, may well have been “slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.”

Reading Yeats always brings me back to my earliest days as a reader and writer. At 20, I left United States for nearly seven years in Scotland, a student at St. Andrews. I went via Ireland, first making my way to County Sligo, the so-called Yeats country. I went to Drumcliffe, the village where Yeats is buried lies in a modest graveyard under the shadow of Ben Bulben, with a searing epitaph (his own words) on the headstone:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

I wasn’t, however, quite ready to cast a cold eye on anything, not yet. I wanted to make my own way as a poet.

In St. Andrews, I soon met Alastair Reid, a poet, essayist, and translator. Then in his forties, he lived in a stone cottage by the North Sea with his young son. He did a little teaching, but he mostly wrote for a living, often for The New Yorker. He had begun translating several major Latin American writers, including Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda.

Through a mutual friend, we met at pub in the village, drank several pints of beer, ate sausages, and talked about poetry throughout a wet October afternoon. I talked about my hope to write poems, and Alastair said: “It’s as much about reading as writing. Read poetry every day, live in the poems, and then imitate them.” He noted that I had arrived in Britain at a good time for poetry, as any number of splendid poets had hit their stride, including George Mackay Brown and Norman MacCaig—two of the best Scottish poets of that era. He urged me to get their latest volumes, and I soon did. The English poet Ted Hughes had produced a handful of books by this time, and Alastair loaned them to me. They quivered with raw life, taking readers by the throat. (Crow appeared in 1970, just two years after I arrived in St. Andrews, challenging readers with a fierce, amoral vision.) Seamus Heaney had just begun his astounding journey in poetry, gathering images from his childhood in Northern Ireland, finding a language adequate to his experience, setting the air around him alight with a uniquely palpable diction, with an odd, extravagant music. And Anne Stevenson, an American who lived now in Scotland, had recently published some of her best work: fiery, brittle, intelligent poems like shards of broken glass.

I quickly gathered a small library, reading the work of these poets avidly, taking on their voices, allowing my voice to play off theirs. And I would bring my latest efforts to Alastair, who would sit beside me at his kitchen table with a mug of tea, crossing out words and phrases, suggesting new ones, sometimes rearranging stanzas. Perhaps the first poem of mine—it’s the earliest poem in my New and Collected Poems (2016), was written then. I know that because I remember Alastair moving the stanzas about. It was, perhaps fittingly under his mentorship, a rough translation of a poem by Ovid. It’s called “Amores (after Ovid),” and its music owes everything to Alastair, whose poetry I had more or less memorized within months of meeting him:

Amores (after Ovid)

An afternoon in sultry summer.

After swimming, I lay on the long divan,

dreaming of a tall brown girl.

Nearby, a din of waves

blasted in the jaws of rocks.

The green sea wrestled with itself

like a muscular beast in the white sun.

A tinkle of glasses woke me: Corinna!

She entered with fruit and wine.

I remember the motion of her hair

like seaweed across her shoulders.

Her dress: a green garment.

She wore it after swimming.

It pressed to the hollows of her body

and was beautiful as skin.

I tugged at the fringe, politely.

She poured out wine to drink.

“Shy thing,” I whispered.

She held the silence with her breath,

her eyes to the floor, pretending,

then smiling: a self-betrayal.

In a moment she was naked.

I pulled her down beside me,

lively, shaking like an eel—

loose-limbed and slippery-skinned.

She wriggled in my arms at play.

When I kissed her closer

she was wet beneath me and wide as the sea.

I could think of nothing but the sun,

how it warmed my spine as

I hugged her, shuddering all white light,

white thighs. Need more be said

but that we slept as if

the world had died together with that day?

These afternoons are rare.

“That’s your voice,” said Alastair, giving me a verbal pat. But I knew that it was his as well, with its Celtic twang, its iron whimsicality, its sly indirection. These characteristic move through “Daedalus,” a touch poem about father-and-son. It begins:

My son has birds in his head.

I know them now. I catch

the pitch of their calls, their shrill

cacophonies, their chitterings, their coos.

They hover behind his eyes and come to rest

on a branch, on a book, grow still,

claws curled, wings furled.

His is a bird world.

Through Alastair I met in person any number of the poets he admired, including Mackay Brown, MacCaig, Anne Stevenson and, to my amazement, both Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda. Stevenson became a good friend, and she lived in Glasgow with her partner, Philip Hobsbaum. I would sometimes make my way by train to their flat for Philip’s Sunday evening seminars. One brought copies of new work and passed them around, and Philip—a ferocious reader who had honed his critical skills under F.R. Leavis and William Empson—would pounce on weak verbs, stray adjectives, fuzzy nouns. He once quite literally tore a poem of mine into fine strips and dropped it on the floor when I said I wasn’t sure what I meant by one line that he called into question. “Never write a single line of poetry that you can’t yourself understand,” he told me.

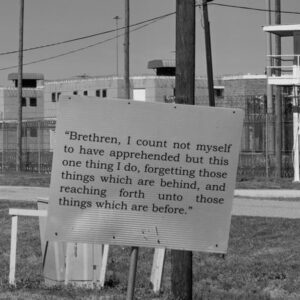

He believed passionately in poetry as the truest form of expression, an antidote to the loud and poisonously empty language that rattled in the public sphere. “There is so much idle talk,” Philip said to me once. “Poetry passes through idle talk, but it arrives in permanent speech. It’s the ‘still small voice’ of scripture.” I remember sitting with him once with Wordsworth open on our laps on a spring afternoon, and we read aloud several of his most famous lyrics. “He has the most subtle mind and ear in English poetry,” he told me. I still have that well-marked copy of Wordsworth the bookshelf in my study, and at difficult times I open it, and I can still hear Philip reading.

I came to poetry as a young man who found something essential there, something that had been missing in my life. Five decades later, poetry has never to me seemed more necessary, with its granularity of diction, its precise metaphors, its bracing clarity. I even find its obscurities productive, as it moves at times to the edges of meaning, gesturing into the silence in which it rests. It’s the rare day I don’t begin my day’s work with a book of poems open on my lap. ( I try not to read the news until later, and when I do—especially in the past year—it has been demoralizing.) I have, of course, my favorite poets—a whole wall in my study is devoted to poets from Chaucer and Shakespeare and Hopkins to Adrienne Rich, Charles Wright, and many others. A few poets—Wordsworth, Hopkins, Yeats, Frost, Stevens, Eliot, and Auden – remain touchstones, worth reading again and again.

When I started writing, I imagined I would only write poems. And I have never stopped writing poems. But soon prose entered my life—I started with literary criticism, as a graduate student, but soon tried my hand at fiction. I later moved into biography, personal essays, and political commentary, even screenplays. To be frank, I’m half startled that I’ve written so much prose—all so unplanned.

I often recall Alastair saying that poetry, for him, occupied brief periods of startled awareness, the stuff of “inklings, oddments, omens, moments.” Prose was, in his view, a medium in which one could address the mundane world, its emotional sprawl, gathering strands into a woven fabric that somehow mirrored reality, even became it. I would myself hesitate to make too much of the distinctions between poetry and prose: at their best, they both move toward passionate expression, refinement of feeling, a kind of freedom in language and thought that is hard to find in the usual straightjacket of every discourse, where cliché and imprecision reign.

This political season has been especially jarring for those who crave the freshness, the linguistic and moral challenges, of good poetry. In such times, I often reread “What Kind of Times Are These” by Adrienne Rich, who repeatedly faced—as a poet—the harsh, unpleasant realities of American life, with its coercions, its barbarous emotional dislocations. This brief poem opens with an image of place: an “old revolutionary road,” which for her calls up memories of early upheavals, forgotten acts of violence, summoning “the persecuted / who disappeared” into the shadows of certain trees. For me, the poem recalls the aggressions of early settlers and the death of native peoples, the Mexican War, the horrors of slavery. Rich suggest that she has walked in those places “at the edge of dread,” and reminds us that this isn’t some “Russian poem.” It’s an American poem, a country birthed in sprays of blood, and which lives in the repressed knowledge that lingers at the edge of everyday consciousness.

Rich moves into “the dark mesh of woods.” Like everything in America, this forest is for sale at a price: “I know already who wants to buy it, sell it, make it disappear.” She concludes:

And I won’t tell you where it is, so why do I tell you

anything? Because you still listen, because in times like these

to have you listen at all, it’s necessary

to talk about trees.

We all want talk about the trees, after all: nature soothes us. It’s more difficult to talk about violence, which runs from the early Indian wars of colonial America through our current hostilities in the Middle East, with recent threats of “carpet bombing” (a hideously inappropriate metaphor) raised by politicians running for high office. In times like these, as Rich notes, we look around us and begin to feel the presence of the past, with its sour echoes in contemporary realities. In the language of good poems, with a bit of luck, we find ourselves lifted as well as exposed by what we discover. We occupy an inner landscape, where the voice of poetry itself—refracted a thousand ways in individual poetic voices—moves toward what Heaney once called “a restoration of the culture to itself.”

Jay Parini

Jay Parini is a poet, biographer, and critic who has published seven novels, most notably The Last Station, which was made into an Academy Award-nominated film in 2009 and translated into over 25 languages. He is the D. E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing at Middlebury College, and the author of Promised Land: Thirteen Books that Changed America.