I’ve known Walter Bernstein for 30 years. In all my adult life I have never met a more intelligent, loving, sensitive, questioning, heroic man. Whether putting his body in the way to block stones hurled at Paul Robeson or marching across nighttime, Nazi-dominated, Yugoslavia to be the first American to interview the insurgent Josep Broz Tito—a hero in his own right. Walter underwent LSD psycho-therapy in the 1960s and wrote some of the most beautiful scenes ever seen on the movie screens that most often lie to us. He interviewed the great Sugar Ray Robinson while riding shotgun in his pink Cadillac and worked closely with the incomparable Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte.

At once Walter is an original and a filial brother in arms. His convictions and beliefs were often dangerous for him and his loved ones. His socialism, for instance. Many of us, maybe all of us, have convictions and beliefs but how many have the courage to stand up for what we believe and behind others who have no choice but to fight? Not many I think. For this reason alone there is greatness to Mr. Bernstein.

Today, Tuesday, August 20, 2019, Walter will celebrate his 100th birthday. One hundred years fighting the good fight with his body and mind, his love of justice and an open heart. One hundred years of sharing his larder, his knowledge, and his restless pursuit of what is right in the midst of chaos, prejudice, stupidity, and downright evil. One hundred years searching for the right words and images while celebrating any and all who join in this endless, completely human adventure.

Walter agreed to a short interview concerning the previous hundred years. I didn’t ask about his parents or siblings, his elementary school experiences or his first love. Instead I talked about a life lived in a land of potentials and pitfalls.

*

Many years ago I asked Walter what it was like to be on Joe McCarthy’s Blacklist.

For those of you who don’t know the senator from Wisconsin: Joseph McCarthy fanned the fires of hatred for anyone who might have believed in some aspects of socialist reform. McCarthy and his supporters developed a list that came to be called the Blacklist. If your name was written there you could be banned from government and other jobs. People’s lives and careers were destroyed by this list. Some went to prison. Some left the country. Some even committed suicide.

Walter Bernstein serving in Italy, in WWII.

Walter Bernstein serving in Italy, in WWII.

But as I was saying. . . Walter Bernstein was on this list. He was definitely a socialist. He believed that capitalism was not a close relative of democracy.

So I asked Walter what it was like to be on that dreaded list.

He said, “I was standing on the subway platform waiting for my train with everyone else. The train pulled into the station and a car stopped in front of me. As the doors opened I felt a tap on my shoulder and so I turned around. Two men in cheap suits stood there. One of them said, ‘Are you ready to talk, Mr. Bernstein?’ I shook my head and got into the train. The doors closed and the two FBI agents watched me as the train pulled away.”

Walter is quite loquacious at dinners and parties, hanging out with peers or helping students at the Sundance Institute figure out what’s going on in their screenplays. He remembers every book read, movie seen, and conversation he’s ever had. But when it comes to interviews his answers are brief, concise, and succinct. After all Walter has been a screenwriter for well over half a century. Extraneous words in a screenplay can only lead to confusion. His lessons come from Hammett and Hemingway. He is never the subject but only the arbiter of the language that tells the story.

When I asked Walter B. about attending a certain Paul Robeson concert in Pittsfield, Massachusetts he said that he and his friends knew there could be trouble because there were demonstrations planned against the internationally famous bass baritone, pro-communist black man—Robeson.

“And was there trouble?” I asked Walter.

“Only because of the cops,” he said.

“The police were on the side of the demonstrators?”

“They protected the right wing protestors and then attacked and arrested many of us. It didn’t matter though—because we kept Paul safe from harm.”

“How did you do that?”

“We surrounded him so they couldn’t get at him.”

“And did you get arrested?” I asked Bernstein.

“No. I was lucky. I only got beat up a little.”

After activism I decided to ask Walter about his adventures with LSD. Back in the days when the psychedelic drug was not yet outlawed it was the subject of much speculation and experimentation.

“I had two therapists back then,” Bernstein said. “A regular psychotherapist and then another one who would give me LSD. I’d take the drug and then the therapist would lead me through the hallucinations and revelations trying to get at the deepest motivations of my psyche.”

“What was it like?” I asked.

“It was the difference between prose and poetry,” Walter B. said and then he went quiet. Being a poet in his own right, Walter thought this was the complete answer to the question.

When I asked for a little more he said, “Regular psychotherapy brought you to the inner issues step by step. It was a long journey. You had to sift through all the experiences and unconscious responses before you could get to the meanings. A very long process. A thick novel. But LSD took you right to the heart of desire, fear, and wonder.”

“It was like a shortcut?”

“I wouldn’t call it short. The sessions would sometimes last three or four hours.”

“Was it worth it?”

“I don’t know if it did me any good or not but I enjoyed the experience.”

“Why would you even consider such a radical approach to therapy?”

“For the hell of it,” he said. “A lot of other Hollywood types like Cary Grant were doing it. And my girlfriend at the time was into it and so . . .”

*

Having mined drugs enough I turned to the subject of Sugar Ray Robinson, widely regarded as the greatest pugilist in history. Walter was tasked with interviewing Robinson and Ray agreed to allow the young journalist to come with him around Harlem.

“I didn’t really like the guy,” Walter B. said.

“Why not?”

“He was too full of himself. He knew how good he was and said so. He spent the time picking up women and soaking up the love of Harlem—a neighborhood that needed heroes.

One hundred years of sharing his larder, his knowledge, and his restless pursuit of what is right in the midst of chaos, prejudice, stupidity, and downright evil.“But he really was great. That night we went to a boxing match and he dissected it for me in ways I never would have seen. I remember in one fight Ray said of one of the contestants, ‘Georgie’s doing business tonight.’ The superior boxer had been paid to take a dive. And when Robinson said it I could see that a whole other contest taking place.”

Walter had boxed as an amateur in the army. He was a lightweight and very good. He knew many boxers in New York in the late 1940s through the 60s. He can talk sports for days.

“Walter,” I said after hearing about the unequaled Sugar Ray, “what do you have to say about socialism after all this time?”

This question got a sigh and pause from the veteran filmmaker.

“I still am,” he said, “–a socialist that is. Maybe half-assed, maybe not clear on how change is to take place but I still believe that we have to have a Marxist edge against Capital.”

Sometimes the poetry of description is enough.

*

Sundance Institute began under Robert Redford in 1980. It is an organization committed to the growth and well-being of filmmaking, among other related arts. Walter B. was there from the beginning—teaching, talking, celebrating and trying his best to share his considerable knowledge with novitiates and peers.

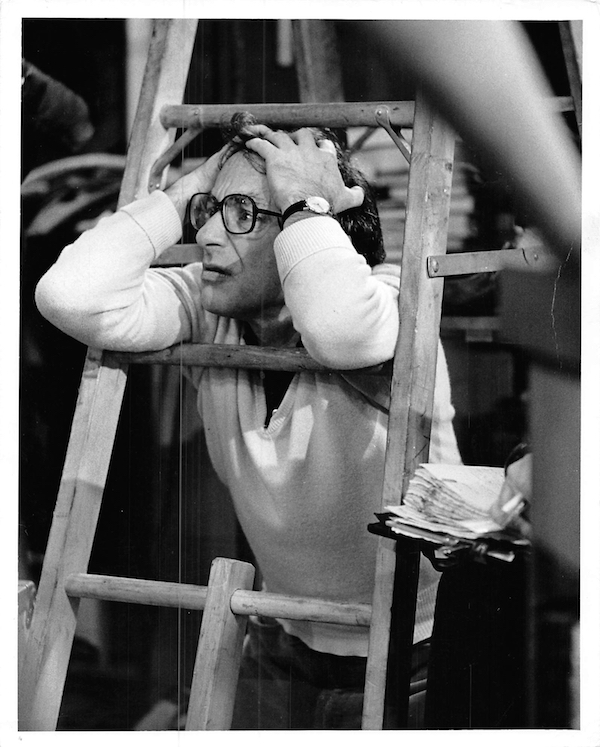

Walter B. on set.

Walter B. on set.

I asked Walter to tell me how he felt about the Institute and what it has become after all these years.

In typical Bernstein fashion he said, “Sundance is a very important place for filmmakers and filmmaking. It’s a place where people come to learn and to experience each other as equals. It is a state of grace.”

*

Walter has been married four times. Among the first three wives he has four children. It wasn’t until later in life that he met and married literary agent Gloria Loomis. I have seen the two together for decades and I can say that there has not been a moment between them, in my experience, that has not been backlit by love. And so I had to ask Walter about Gloria.

“What can I tell you?” he said. “I met her, intruded on her life, and she took me in. I’m just lucky, I guess.”

*

At the end of our hundred-year excursion I asked Walter what he thought his greatest accomplishments were.

Without hesitation he said, “Surviving.”

He was silent for a few beats after that and then said. “Holding onto my socialism, standing up for what I believed. I think I did that okay.”

He had done. And I would have left it at that but because this is Walter B. and movies are his métier I had to ask one more question.

“So, Walter, what film of yours are you the most proud of?”

He took maybe 15 seconds to think about all the wonderful works he’d put out in the world and then said, “The Molly Maguires. Yes. The Molly Maguires.”

I don’t think he could have made a better declaration. The Molly Maguires—a secret society of miners who fought for the rights of the men who delved into the earth for the betterment of the world. Men who were ill-paid, overworked, and considered disposable. Men who stood up for what they believed, many of whom paid for it with their lives.

Walter along with his blacklist friend, director Martin Ritt, along with the actors Sean Connery and Richard Harris. They did some truth-telling in that film. It was a box office flop but still it’s what Walter is most proud of.

A great man. A man of few words. Walter Bernstein did it in the poetry of life.