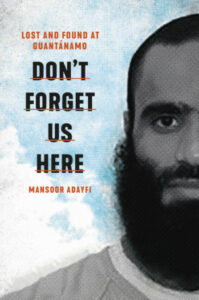

Waiting in Darkness: My Time At Guantánamo

Mansoor Adayfi on the Fifteen Years He Spent As Detainee #441

I waited in darkness for death.

The interrogators were done with me. You aren’t valuable enough to keep alive, they said. I didn’t have the intelligence they wanted on al Qaeda’s chain of command. They bound my hands with duct tape, then taped my eyes and ears. They taped my mouth and then pulled a hood over my head. They dragged me outside into the cold and forced me to my knees. I hadn’t seen the light of day in weeks and I thought I would never see blue sky again. I’d been kept hooded or inside dark rooms, stripped naked, and beaten bloody for I don’t know how long. Weeks. A month. Maybe more. I was in Afghanistan, but I didn’t know where.

If I hadn’t lived it, I wouldn’t have believed what happened to me. It happened so fast and none of it made sense. It all started days before I was supposed to return home to Yemen, when my friend and I were ambushed on the highway in northern Afghanistan and kidnapped by warlords. At first, they just wanted our truck and to ransom us for money.

I grew up in a tiny village in Yemen that had no electricity or running water. I’d been told all my life that I was smart. I was eighteen and full of the stubborn confidence boys can have at that age. I’d never been in a situation I couldn’t talk myself out of. None of that mattered when the United States started bombing and dropping leaflets offering reward money for al Qaeda and Taliban fighters. The warlords got a better price selling Arabs to the Americans.

The warlords told me to say that I was al Qaeda or the Americans would kill me. The Americans told me they knew I was an al Qaeda leader—a recruiter, a middle-aged Egyptian—and all I had to do was admit it. None of it was true.

*

Waiting on my knees to be executed, I wished that I could see my mother one last time to say goodbye. I regretted my sins and the mistakes I’d made, and I prayed to Allah to forgive me, wishing that I was closer to Him and had done more good deeds in my life. One day, we all will stand before Him. He knows I haven’t wronged these people who tortured me. He knows I have caused harm to no one.

A man cried close by. He begged someone to stop beating him. He begged for his life. This wasn’t new. In the endless darkness, I’d heard women and children beg, too. A soldier yelled and then there was gunfire, but it wasn’t for me. My heart pounded through my temples. I cried. Where would the bullet hit me? Would they shoot me in the head? In the chest? Would I feel pain? The rest of my life existed in these seconds and no more. I prayed again to Allah. I wished I wasn’t so cold.

Allah, oh Allah. I bear witness that there is no deity but Allah, I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah. Allah, oh Allah.

I told myself that I would be strong when they came for me. I’ll make them work. I won’t walk. So they dragged me, my toes digging into the dirt. Allah, oh Allah. They threw me to the ground and tore off my clothes and stripped me naked. They searched me in the worst way, and what did they think they would find after I had been tortured and left naked for months? They pulled a hood over my head, put me into a burlap sack, and taped me up. But they didn’t shoot me. They threw me into what I imagined was a truck and tied me to the floor. At least the floor was warm. Engines rumbled to life and shook my entire body. I wasn’t in a truck; I was in an airplane. The engines revved louder and louder and then the weight of the world filled my stomach. Allah, oh Allah.

They searched me in the worst way. What did they think they would find after I had been tortured and left naked for months?

“Let me help you help yourself,” the interrogators had kept saying to me in the black site. “I don’t want to hurt you.”

I’d spent weeks in darkness hanging from a ceiling, naked, beaten, electrocuted until all that remained was pain, real pain, a pain I never imagined existed. I tried to figure out what I could say that would make them stop. I told them the truth—that I was a student, that I was eighteen, that I was from Yemen. I told them I wasn’t a fighter, that I didn’t hate America, that I wasn’t al Qaeda—but they didn’t want that. They wanted something from me I didn’t have to give. They wanted me to admit that I was a man named Adel, an Egyptian al Qaeda recruiter, a terrorist who planned bombings. Fine. “I’ll be whoever you want me to be,” I said. “I’ll be your Adel.”

I said whatever they wanted just to stop the pain. Just because they told me to say it and I did, didn’t make it a sin, but I still prayed for Allah’s forgiveness. Allah, oh Allah. I thought that once I had given them what they wanted, it would all be over. But now they wanted details. Details I couldn’t give them. If I had no value, what would they do with me? At that moment, I lost a part of me I would never get back. The pain, the questions, the torture changed me, and I didn’t know who I was anymore. The person they’d sold was gone forever.

*

When they didn’t execute me, I thought that the worst must be behind me. Nothing happened on the airplane except the sharp contact of boots to my body. The plane landed and I got one more boot to the head and then someone pulled me up and tore open my bag. They wanted me to walk but I couldn’t. Allah, oh Allah. I wouldn’t. One of them put me in a chokehold and dragged me off the plane, punching me in the face, the ribs, the head. He threw me on a pile of bodies, like slaughtered sheep, and that’s where I stayed. How many others had they disappeared like me?

Noise and movement swirled around us, people talked and shouted in English I couldn’t understand. I couldn’t see. I couldn’t think. Allah, oh Allah. We stayed like this for hours, naked and duct-taped and hooded, freezing in the open wind as soldiers kicked us, peed on us, spit on us, put their boots on our necks. All of it humiliating but minor compared to what they’d done to me before.

Allah, oh Allah. Time melted and then someone dragged me away from that pile of bodies. They took the hood off my head, then ripped the duct tape from my mouth and ears but not my eyes. A man spoke in English and another talked into my ear in Arabic.

“Are you with al Qaeda?” he asked. “No.”

“Are you with the Taliban?” “No.”

“Are you a fighter?” “No.”

“Have you been to al Farouq training camp?” “No.”

“Do you know where Osama bin Laden is?” “No.”

“Do you know where Mullah Omar is?” “No.”

“Do you know where Khalid Muhammed is?” “No.”

Allah, oh Allah. I said no over and over and then they shoved something in my ass. That’s when I fought back. My hands were taped but I kicked. I kicked and shouted. Then a mountain of soldiers piled on top of me, pounding me with fists and boots. When they were done beating me, the guy asking the questions came back.

“That’s what we do to people who lie to us,” he said. “You want some more? Don’t worry, you’ll get more.”

They tore the duct tape from my eyes. The bright light burned after months of darkness. Someone stepped in front of me and took photos of my face, my naked body, everything. My eyes adjusted and my surroundings came into focus. I was in a tent. There were soldiers everywhere; some wore masks and white protective suits splattered with blood. There was blood everywhere. One of the soldiers was beating a naked man. In one area were bags of clothes—where were the men who wore those clothes? Allah, oh Allah. Is this where they kill me?

“That’s what we do to people who lie to us,” he said.

I was told to sign a piece of paper that said if I tried to escape, they had the right to shoot and kill me. I refused. If they were going to kill me, I wouldn’t sign my own death certificate. They hooded me again and shackled me.

And then I heard a distant voice, a woman’s voice that reminded me of my mother and lifted me away from fear. I tuned out all the other sounds around me, the beatings, the engines screaming outside. I focused on that one voice, sweet and calm like my mother’s, and that voice brought me to life again. She spoke in English and I didn’t know what she said, and it didn’t matter. That voice transported me to a place in my heart where there was no more pain or suffering or fear. When I listened to her voice, I found peace in something my mother had always said to me when putting me to bed: Allah will never abandon you.

When they came for me, I was calm. They loaded me on a stretcher, naked except for the hood and shackles, and carried me away. Gates clanked open and closed. They put the stretcher on the ground, replaced my shackles with duct tape, and left. I waited in darkness for something to happen. And when nothing did, I reached up and took the hood off my head.

Bright lights lit everything like day. Generators roared. Soldiers shouted. Helicopters hovered above. Freezing cold slashed my weak and broken body. I was in a large open tent wrapped in barbed wire. I could see five other tents. None of them had walls protecting the inside from the cold and blowing snow. Outside were five towers, each topped with soldiers armed with heavy machine guns. American soldiers in desert uniforms swarmed everywhere.

I found a blue jumpsuit on the stretcher next to me and put it on, the first real clothing I’d worn in months, since I was first kidnapped. I was so happy that I could finally cover myself. The night was so cold. All around me were men bundled up in blankets trying to shield themselves against the icy wind.

I had never seen anything like this. The armored trucks, the helicopters, the number of soldiers with machine guns. Nothing made sense.

“Where are we?” I asked out loud, not expecting an answer. “You are at the American prison camp in Kandahar,” a voice said in Arabic.

I lay back down on the stretcher. I was all the way south! Allah, oh Allah. I was so tired. I was so hungry and thirsty. Finally, I slept. And in my dream, I saw myself in a metal cage wearing orange. I was woken by that beautiful voice again, talking quietly close by. I didn’t know what she said or whom she was talking to, but I closed my eyes and listened to this lovely voice until it faded away. That woman’s voice was the voice of life, like a mother’s whisper that says, Everything is going to be okay.

I believed this.

________________________________________________

Excerpted from DON’T FORGET US HERE: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. Used with the permission of the publisher, Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Mansoor Adayfi.

Mansoor Adayfi

Mansoor Adayfi is a writer and former Guantánamo Bay Prison Camp detainee, held for over 14 years without charges as an enemy combatant. Adayfi was released to Serbia in 2016, where he struggles to make a new life for himself and to shed the designation of a suspected terrorist. Today, Mansoor Adayfi is a writer and advocate with work published in the New York Times, including a column the Modern Love column "Taking Marriage Class at Guantánamo" and the op-ed "In Our Prison by the Sea." He wrote the introduction, "Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantánamo Bay," for the 2017-2018 exhibition of prisoners' artwork at the John Jay College of Justice in New York City, and contributed to the scholarly volume, Witnessing Torture, published by Palgrave. In 2018, Adayfi participated in the creation of the award-winning radio documentary The Art of Now for BBC radio about art from Guantánamo and the CBC podcast Love Me, which aired on NPR's Snap Judgment. Regularly interviewed by international news media about his experiences at Guantánamo and life after, he was also featured in Out of Gitmo, a mini-documentary and part of PBS's Frontline series. Work from his memoir was recently featured at a public reading at the Edinburgh Book Festival along with work by Guantánamo Diary author Mohamedou Ould Slahi. His graphic narrative, Caged Lives, was by The Nib and will be included in the anthology Guantanamo Voices. In 2019, he won the Richard J. Margolis Award for nonfiction writers of social justice journalism.