How do immigrant writers respond to COVID-19? In what way has it affected their dreams? Has the understanding of the future also been recalibrated? This is an edited version of a Zoom conversation between Jhumpa Lahiri, Eduardo Halfon, and Ilan Stavans that took place on July 23rd, 2020.

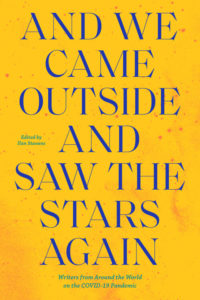

Lahiri was in Rome, Halfon in southern France, and Stavans in Cape Cod. Stavans is the editor of the new anthology And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again: Writers from Around the World on the COVID-19 Pandemic (Restless Books), which includes pieces by Lahiri, Halfon, and segments of an email correspondence that Stavans and New Yorker journalist Jon Lee Anderson have held since the pandemic began.

*

Ilan Stavans: My dreams lately have been more vivid that usual. The texture in which they unfold is intense. I seldom remember my dreams, but now I wake up disturbed in the middle of the night, not because of the images I witnessed in my dreams but because I feel that the emotions they’re conveying are raw, urgent.

Years ago, an Indian friend told me that we don’t dream of a tiger and then feel scared. It is the other way around: we are scared and then we dream of a tiger. Have your dreams been different since the pandemic began?

Jhumpa Lahiri: Last night I had a classic COVID nightmare. My brother-in-law was coming to visit. He had a fever. Then my son Octavio also had a fever. I was frantically trying to understand what to do. I also had an interesting dream early on in the pandemic, while I was still in Princeton. I was flying in a very small airplane with a couple of friends. I was exhilarated to be in the air. I looked down at one point and saw the ocean, which, as you know, Ilan, I have a great passion for.

I hadn’t seen it in a long time. At first I was thrilled. But then I saw hundreds and hundreds of people on the beach. My friends on the plane and I decided we needed to go somewhere else and I was relieved to leave the crowds behind. Clearly, these dreams are expressions of basic fears, about searching for safety.

IS: Did you wake up anxious after either of these dreams?

JL: Yes, I woke up feeling anxious both times. Dreams are so inherently mysterious. Some remain with us, coherent, and others are just fragments. But yes, my dreams, in general, have been more intense in recent months. There is also the awareness of waking up and every day having to confront the truth again.

One of the reasons I’m grateful to be in Rome is that it is a place I love very deeply. When I wake up, I’m concerned. But I’m also happy to be here. I feel protected. I would feel similarly if I were in Wellfleet, another place I very much love and feel at peace in.

When COVID broke out and we realized what we were headed for, I remember thinking I wanted to be in a coma for the next year. “Wake me up when it’s over. I don’t want to deal with it.” Then I stopped saying this to myself, because sometimes you get what you wish for. It is all so grim, and we are getting so tired of it. It has been disheartening for those of us in the United States who followed the rules. In Italy, my friends say, “we made an intense sacrifice, the whole country, every single person took part, otherwise we would have faced the consequences, including fines.”

And now that they’ve emerged from it, after truly flattening the curve, there’s a sense of relief, even of cautious exhilaration. Of course, people are on standby, wondering if there will be a second wave. On the whole, in Italy, the entire country can now say: that was then and this is now. We can’t say that in the United States. There has been one tsunami followed by another. It’s all a big mess. It’s hard to sustain, mentally and emotionally.

Going back to dreams, I’m sure we’re hungrier than ever to explore our unconscious. Especially those of us who haven’t been able to travel. My family and I are fortunate in that we managed to come to Italy. Most people I know have been stranded.

Eduardo Halfon: From the beginning, more than my dreams it was my sleep that was affected. The pandemic hit us in Paris. It was painful to see a deserted Paris. And the uncertainty of what was happening outside affected my sleep. We were away from home. We were guests in Paris—I had a fellowship from Columbia to spend a year there, writing. And not being in my own environment, not having a personal doctor, not knowing how the health-care system worked—these variables disturbed me. I was thrown into a constant state of anxiety.

I also started dreaming about family members getting sick. Not with COVID, necessarily, more of a general sickness. I think it stemmed from the fact that if someone did get sick—my father, my mother, my brother, my sister—I would not be able to be with them. That made me feel even closer to my wife and my son, who were there with me.

But I kept thinking how the pandemic would have affected me if I weren’t a father or a husband, if it was just me. Would it have been easier? Would I have been able to work more? I wouldn’t have had to take care of anyone, or to worry about either of them getting sick—my biggest concern. Although, at the same time, I couldn’t imagine spending two months of lockdown without them.

Yes, writing was difficult if not impossible with a toddler at home, but I was also too busy keeping him busy, playing and inventing with him new games, sheltering him from what was going on outside, in the streets. We were bunkered down together.

IS: In spite of the anxiety, I confess to also have enjoyed quarantine. I’m sure I’m not the only one. It has come as a respite. Not to travel, not to be constantly on the move. In my case, I have rediscovered the tranquility my home has always given me. I had taken it for granted. Now I cook more. Alison and I take long walks. Mixed with the anxiety, and frankly the fury at the ineptitude of our government, is also a sense of gratitude.

My writing feels different, too. I relax better while I’m writing. I’ve always enjoyed it. But now I do more. Perhaps it is because I have thought much more seriously about finitude. I only have a limited time. Things will suddenly end. I will not be myself at some point.

“I haven’t been able to be with my mother, who lives in Mexico City, for a long time. She is absolutely alone in her apartment.”Somehow, I have noticed the birds more than before. Cardinals, finches, hummingbirds, blue jays. Alison put up some feeders. The birds come regularly. Their movements are nervous. They have always been. But I see that nervousness now more emphatically. In Wellfleet, we have also been visited by wild turkeys. A large family: the parents and about eight chicks. They go about their way without worry. I envy them, honestly.

Jhumpa, I notice in your words anger toward the United States, a feeling to want to keep the country at arm’s length, far away from you. We’ve talked about it at dinners. Is it more pronounced? Isn’t what is happening to this country predictable? The excess of individualism, the libertarian response to government rules, the conviction that everyone is exceptional. It all has been in the collective DNA. The pandemic and Donald Trump’s ineptitude have simply made the fault lines more visible.

JL: It certainly helps me, when I live in the United States, to have another point of reference, another home—socially, culturally, linguistically. Octavio was going to school in Italy this year while the rest of us were living in Princeton. Having my son in Rome meant that I was always rooted in two places, and this caused me to have even more perspective.

For the past eight years, I have been cultivating an intense relationship with Italy, and especially with Rome where I now live part of the year. Of course this is a big investment: of time, of energy, of finances. But as a result I always think to myself: if things get bad in the United States, we can leave. I especially felt it after Trump was elected. It was enormously reassuring. Like so many, I was in a deep state of shock, mourning, and terror. But I had the keys to my Roman apartment in a coffee can in my study in Princeton. All we had to do was book tickets.

Ironically, when COVID hit, I couldn’t leave. I had a job. There were roots, responsibilities. Literally, the solution I had created wasn’t possible. That was hard for me to accept. I had to stay put, obey the rules, and hope things would slowly improve. And they have, otherwise I wouldn’t be in Italy now. However, the freedom one feels is tentative. It’s still a risk to move around. Things are uncertain.

I feel anger, of course. I think one of the best aspects of America is also one of its limitations: freedom to a fault. The insistence on doing it my way without thinking about the collective. False statements of patriotism mean nothing to me, but sacrificing for the greater good means a great deal. There has been a total lack of leadership, by a dangerous man. It’s the perfect storm. We needed someone to say, “Listen up everyone! This is very serious. We have to all work together. We have to listen to the scientists.” That message never came. It’s a buffet style approach to society. We needed a seated dinner with a fixed menu.

In Italy, on the whole, there’s a greater sense of community, and far more day-to-day interaction involved in living one’s basic life. There’s less isolation, less alienation. I miss that when I’m in America.

IS: I haven’t been able to be with my mother, who lives in Mexico City, for a long time. She is absolutely alone in her apartment. I talk to her every other day but it isn’t the same. And I haven’t been able to hug my son Josh, who is in Brooklyn. I miss the love that comes from the day-to-day physicality. You come from a diasporic Jewish family, Eduardo. You were raised in Guatemala and studied in the United States. I think of you as an expat, although I don’t know that the “ex” refers to. What is the center of gravity for you and your family? Do you also approach the pandemic as an immigrant?

EH: I approach everything as an immigrant. I’ve always approached everything as an immigrant. I come from an immigrant family. I was raised that way. Always on the move.

In my life, I’ve experienced two different United States: in the 1980s growing up in South Florida, and then the decade I spent recently in the Midwest—in Nebraska and Iowa. Two completely different experiences. In the latter, I arrived in Lincoln just as Obama had been elected. The atmosphere was optimistic. Like both of you, I had always been attached to universities, which are like an oasis. International students, international faculty. It was easy.

Then came the nightmare of Trump’s election. As a Latin American, I immediately sensed in him the type of bully we are accustomed to south of the border. A con man. A shyster—a wonderful word, difficult to translate into Spanish. It isn’t an accident that what is happening in the United States right now, with the pandemic out of control because of a complete lack of leadership, is also happening in Brazil and other Latin American countries, Guatemala included.

“My grandparents were Jews from Poland, from Lebanon, from Syria, from Egypt. Like them, I live on the move, ready for the next place.”But I see all of this from the outside. Although I’ve lived in the US almost half of my life, I have always seen the country as an outsider. I never became an insider, never became a citizen (I was always there with some type of visa), never felt like an American, although I could pretend to be one. But when I’m in Guatemala I feel the same. Likewise in Spain. Likewise here in France. I’m never completely at home anywhere. You see those suitcases behind me? They’re still full. I haven’t taken all of my clothes out. I didn’t while I was in Nebraska, either. I always have them ready to go. Mine is an itinerant life.

I like, Ilan, that you used the word “diaspora.” My grandparents were Jews from Poland, from Lebanon, from Syria, from Egypt. Like them, I live on the move, ready for the next place. Always hovering everywhere, never landing anywhere. I was educated that way: to always be at the ready. So when COVID arrived, I was of course ready to move. Suitcases packed, let’s get out of Paris. And we did, to a small town in southern France. In due time, however, I’ll also get out of southern France.

My son is three and a half. He has already moved six times. He has three passports. Clearly, this itinerant life is continuing. It’s a nomadic existence, a Jewish type of life.

IS: In the earlier days of the pandemic, my sons, just like everyone else, kept talking about going back to “normal.” In the last few weeks, I have noticed they no longer use the word. They are in their twenties. I have asked them, separately, what they think the future will look like. Neither believes inthe same future they envisioned in December, for instance.

The future, as a dimension, has been utterly reconfigured. To them it now feels more tentative, less forgiving. By this I mean the conviction that you might do anything you dreamed of in it. Maybe not anymore. What do you think?

JL: The future is by definition an unknown. We all have hopes, plans, expectations. But life teaches us again and again that nothing apart from the present moment is within our grasp. This has been one of the great lessons of Rome for me personally, and I hope, also for my children: to live each day with appreciation and with awareness, knowing that tomorrow everything could change.

History teaches us and the pandemic now reminds us, acutely, of how precarious life is, how little we still know. It’s a sobering reality, especially for young people. But honestly, my children have faced the considerable disruptions caused by the pandemic with extraordinary strength, patience, and even-headedness. They have never despaired the way they did the night Trump was elected.

EH: I can’t help thinking that the opinion about the future of someone like me, that is, someone of my socioeconomic standing, would be radically different from, say, the opinion of a poor indigenous Guatemalan or a poor rural Nigerian. For them, the future has always been tentative, unforgiving, devoid of any possibility of plans or dreams. Their situation hasn’t changed—it’s still day to day, still hand to mouth.

They still struggle every day to put food on the table. They still have no access to health care or adequate schools. Their daily existence is as precarious now as it was before the appearance of any virus. It is only for us, the more privileged, the ones who have lived under the illusion of planning and dreaming up fairytale futures, that things feel as though they’ve now dramatically changed. The rest of the world just put on a mask.

__________________________________

And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again, an anthology of reflections amid the COVID-19 pandemic, is available now.