There Is Grace in Patience: On the Writing Lessons of Tarot

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood Considers Trust, Discovery, and Dreaming While Awake

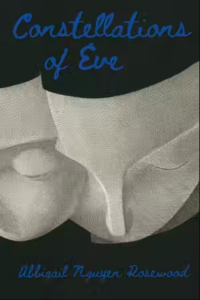

One of the challenges of being a writer is not writing, but waiting. To be a professional wordsmith means to be a professional person-in-waiting, to find a cozy corner in limbo and curl up there with a couple of magazines, tabloids, a few choice hallucinogens, anything to distract the mind from the agony of not knowing. It took over two years and nine drafts to find a home for my second novel Constellations of Eve. During that time, I developed a habit of conferring my deck of Tarot (designed by Yoshi Yoshitani) every morning. Before taking my first sip of coffee, before checking my emails, I would shuffle the cards: nervous, excited, hopeful.

Like many fortune-telling objects—the wishbone, the tea leaves at the bottom of a china cup, the magic 8-ball, the stars—Tarot is an object of hope. As I drew a card, I would ask questions, the kinds you might expect from a writer: Will my novel ever find a home? Will today finally be the day? Sometimes the cards were generous, showing up as an upright Page of Coins, meaning “talent shines and money news.” Other times, my heart would sink at the appearance of The Tower.

Surrender, the card says.

You mean give up? I ask.

You can’t resist change.

The message is, of course, open to multiple interpretations: therein lies the power and seduction of Tarot. Randomness or synchronicity is up to the seeker to decide. The cards provide an axis for my desperation and obsessive thoughts. Much like writing, Tarot is a framework from which random events can be aligned and given meaning. Instead of vague despair and frustration, my feelings are anchored: it’s not that my book is horrible, I would tell myself, it just isn’t the right time for it yet, as the cards clearly show.

In America, a culture of heroes, people often attribute success to their lone effort and harshly blame themselves for failures, rather than seeing the wheel of fortune at work and the whims of the heavens at work. Alain de Botton, writer and philosopher, believes that, “we live in an age when our lives are punctuated by career crisis, by moments when we thought what we knew about our lives, about our careers, comes into contact with a threatening sort of reality.”

With American meritocracy, we gain individualism, but also lose the spiritual guidance and faith inherent to religion. Instead of going to church, we have to develop our own system of faith. Success is almost impossible to measure in the arts, and the writer must deal with their career crisis almost daily. Writing is nothing less than an act of faith, a toiling that would make no sense at all if not for the belief that the work has meaning. Tarot asks us to pay attention to the ordinary, to discover in our own life abundant symbols and patterns. It is a way to insist on meaning.

Suspension does not have to be limbo, I realize. There is grace in patience, in waiting, in trusting the hands one is dealt.

Because what a writer writes is often inextricably bound with how they feel, Tarot can also serve as an emotional roadmap. The work requires a constant engagement with difficult truths, many of which are deeply buried. Tarot art is symbolic, a language dating back to as early as the 13th century that speaks directly to our psyche—a bridge between our physical plane and the divine. At my desk, I would study the chosen card for clues, sometimes with a nearly clinical interest, as to what themes, ideas, and signs I should pay attention to.

Other times, the card worked its way into my inner world the way dreams do, summoning flashes of memories, a vague sense of dread, a color, becoming seeds to a new scene in a novel, a short story, an essay. In an interview with Bill Moyers, Joseph Campbell says, “The dream is an inexhaustible source of spiritual information about yourself.” Using Tarot is a way of dreaming while awake.

My second novel, Constellations of Eve is a modern fable, following three incarnations of one love story. Each reality allows Eve, an artist and mother crippled by fears of being abandoned by those she loves, another chance at fulfillment—but can she get it right? The structure of the three story lines are inspired by Tarot, with each reality represented by a card that I invented. When I first began the book, I wanted to write parallel stories that echo each other, but struggled to find a way to weave them together.

Tarot lends an aura of the mystical and otherworldly to the novel. This allows me to be more playful in the story, to showcase gestures, feelings, atmospheres that might not work in realism. The novel opens with a death and yet not a death, the end and not the end, and the appearance of the cards signals to the reader how to read the story and let them know what to expect. Constellations of Eve is in many ways a continuation of my daily writing routine, drawing cards to imagine different outcomes, different loves, different deaths in both life and fiction.

My preference for the occult, the surreal, is grounded in a childhood spent in Vietnam amongst fields where the grass grew past your head, in candle-lit rooms whenever the electricity shut down across the whole district, on bamboo mats where the adults huddled together to read fortunes on playing cards. Through a spread of cards, I could hear my father, speak to him, imagine him next to me. Dead, but not gone. Whether through prayers, dreams, Tarot, or writing, we are all capable of resurrection. We can travel effortlessly through time and across multiple planes of being; die many deaths. Our lives are chronological, but not only, for as much as we move with our body, we also live with our mind, which is not time-bound.

Tarot reminds me to trust the process to treat writing as an end in itself and publishing as a happy bonus. The Hanged Man card depicts a man suspended upside down, a serene expression on his face. He chooses to be there in waiting, progress defined not only by actions but also suspension. Two and a half years ago, the imprint that was to publish Constellations of Eve didn’t exist yet. Suspension does not have to be limbo, I realize. There is grace in patience, in waiting, in trusting the hands one is dealt.

_________________________________________________________

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood’s Constellations of Eve is available now via Texas Tech University Press.

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University and lives in Brooklyn, New York. Her debut novel, If I Had Two Lives, has been hailed as “a tale of staggering artistry” by the Los Angeles Review of Books and “a lyrical, exquisitely written novel” by the New York Journal of Books. The New Yorker called it “a dangerous fantasy world” that “double haunts the novel.” Her short fiction and essays can be found at Electric Lit, Lit Hub, Catapult, The Southampton Review, The Brooklyn Review, Columbia Journal, and The Adroit Journal, among others. In 2019, her hybrid writing was featured in a multimedia art and poetry exhibit at Eccles Gallery. Her fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best American Short Story 2020. She is the founder of Neon Door, a forthcoming immersive literary exhibit.