The Worst White House Kitchen in History

The Roosevelts Went Well Beyond Ketchup with Steak

Eleanor Roosevelt didn’t care what she ate. She had no palate, she wasn’t interested in food, it gave her no pleasure—or at least people have been saying these things ever since she became a public figure in the 1920s.

“Victuals to her are something to inject into the body as fuel to keep it going, much as a motorist pours gasoline into an auto tank,” her son James once declared, and nobody among her friends or relatives seems to have disagreed. Eleanor herself joined the chorus: she used to say she was incapable of enjoying food. It’s too bad, then, that she never had the chance to study her own paper trail. It’s as long and rich as you might expect from one of America’s most prominent political activists, and it would have surprised her by delivering quite a different verdict. An intense relationship with food ran right through Eleanor’s life, darting into her work, her feminism, and her deepest relationships.

“I am sorry to tell you that my husband and I are very bad about food,” she wrote in response to a query from the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1929. “I do not know of any particular dish which he likes unless it is wild duck.” FDR did like wild duck; he also loved steak, lobster, heavy cream, caviar, and cocktails, but she wasn’t about to admit any of that to the Journal. Instead, she chose to lie, which was sometimes her favorite way to discuss matters of appetite—especially, as we’ll see, FDR’s appetite. But the art of the cover-up, which Eleanor practiced diligently all her life, was difficult to maintain when it came to cooking and eating. Eleanor wrote so often and so copiously about herself, in memoirs and letters and articles, that the truth had a way of spilling out. Over the years, she became a reliable source on a subject she would have insisted she knew nothing about—her own food story. And it isn’t a story about a woman with no palate for pleasure.

Still, it’s easy to see how Eleanor acquired her bleak culinary reputation. By all accounts, the food in the Roosevelt White House was the worst in the history of the presidency. Longtime White House staff began noticing a change right after FDR’s inauguration in 1933. Eyeing the luncheon buffet Eleanor had ordered, the chief butler called the table “sick-looking”—it featured two kinds of salad, bread-and-butter sandwiches, and vast quantities of milk. A few weeks later California senator Hiram Johnson was invited to dinner and told his son afterward that the most ordinary meal they had at home was “infinitely superior” to what he had been served at the White House. “We had a very indifferent chowder first, then some mutton served in slices already cut and which had become almost cold, with peas that were none too palatable, a salad of little substance and worse dressing, lemon pie, and coffee.” Mutton was not on the menu that night; Johnson had been eating dark, dry, overcooked lamb.

Ernest Hemingway, invited to dinner in 1937, told his mother-in-law it was the worst meal he had ever eaten. “We had a rain-water soup followed by rubber squab, a nice wilted salad and a cake some admirer had sent in. An enthusiastic but unskilled admirer.” The visit had been arranged by the journalist Martha Gellhorn, who was a good friend of Eleanor’s and often stayed overnight at the White House. As they waited for their flight in the Newark airport, Hemingway was surprised to see Gellhorn intently eating sandwiches, three of them, and asked her what on earth she was doing. She said everyone in Washington knew the rule: When you’re invited to a meal at the White House, eat before you go.

Formal dinners prompted more elaborate menus and the best White House tableware, but the same desultory cooking. “I suppose one ought to be satisfied with dining on and with a solid-gold service, but it does seem a little out of proportion to use a solid-gold knife and fork on ordinary roast mutton,” wrote Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes in his diary after the 1934 cabinet dinner. Again, he was eating lamb. Guests who had arrived in black tie and evening gowns for the first state dinner of the new administration found themselves sitting down to an early Thanksgiving. Stuffed celery, roast turkey and cranberry sauce, sweet potatoes with marshmallows, frozen pineapple salad, and ice cream with a product called “rubyettes”—grapes that had been colored and flavored to resemble cherries—made up what The New York Times politely referred to as a “traditionally American” menu. The Washington Post was more blunt: “Gentlemen, let us adjourn to a coffee-shoppe!”

Even the return of wine to the White House table, announced for the 1934 cabinet dinner after the long drought of Prohibition, didn’t offer much by way of festivity. The American wine industry was a shambles after 14 years of neglect, with vineyards lost and wineries ruined. French wines were available—Elizabeth Farley, the wife of the postmaster general, treated herself to a glass of imported champagne at the Mayflower Hotel before the dinner—but Eleanor didn’t want the public to think that the new administration was staging some sort of bacchanal in the midst of the Depression. She decided that two “light American wines” would be served and ordered a California sherry and a New York State sparkling wine, limiting the hospitality to one glass of each. As it turned out, overindulgence was not a problem. “The sherry was passable, but the champagne was undrinkable,” Ickes wrote in his diary. He could see Mrs. Farley reacting to her first sip: she nearly grimaced. Eleanor’s consultant on the wines had been Rexford Tugwell, the undersecretary of agriculture, who was born in upstate New York and remained loyal to its struggling vineyards. Late the next evening, Ickes and a few friends joined FDR in his study for an impromptu get-together, and the president, laughing about how awful the cabinet dinner champagne had been, ordered up a couple of bottles of the real thing. They all drank convivially until midnight. Eleanor wasn’t there.

Everyone who ate in the White House seems to have complained about the food—FDR, his aides, the family, old friends, Washington insiders. Even the women in the press corps, who flocked to the all-female press conferences Eleanor held every week and were devoted to her, whispered that a press lunch had been “abominable.”

Yet now and then a positive report surfaces. Louis Adamic, for instance, a prolific writer on issues of American immigration and diversity, was invited to come for dinner with his wife one evening in January 1942. Because FDR rarely socialized outside the White House—he disliked being seen in public in his wheelchair—Eleanor made a point of bringing new people into his orbit when she thought they might interest him. Adamic said later that he had been far too nervous to pay attention to the menu, but his wife told him afterward what they had eaten: rare roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, string beans, salad, and a trifle for dessert, along with wine, champagne, and brandy. She said it was all very good, and she was probably right—since Winston Churchill had arrived unexpectedly. No wonder Adamic couldn’t focus on his plate. The original menu, planned without the prime minister in mind, had been baked fish stuffed with bread crumbs, and a marshmallow pudding.

Serving appetizing food in the White House was hardly an impossible challenge, and previous administrations had managed very well. The Hoovers, unpopular though they were, never had to field criticism about the menus or the cooking. On the contrary, Lucius Boomer, manager of the Waldorf-Astoria, had lunch at the White House after Hoover was trounced in 1932 and said he had never tasted food so delicious. (Ava Long, the housekeeper at the time, whom Eleanor replaced, pointedly included this anecdote in her reminiscences.) But the fact that a decent meal for Churchill could be summoned on such short notice makes it all the harder to understand why the typical state of White House food should be so dreary. Nobody expected the White House to serve roast beef and champagne every night during wartime, but Churchill didn’t just get a special menu, he was treated to careful cooking as well. The Roosevelts were accustomed to dry, leathery roasts; Churchill’s was properly rare.

What happened in 1933? Why did the food deteriorate so spectacularly? Most historians blame Eleanor and what they assume to be her indifference to matters of the table. After the election, according to this theory, she quickly hired a housekeeper and a kitchen staff for the White House and then threw herself into what mattered far more to her—civil rights, women’s equality, poverty, housing, employment, and the war. She was the busiest, most public, most productive First Lady in history, and complaints about dinner just didn’t register.

But this explanation ignores nearly everything else we know about Eleanor, beginning with her extraordinary talent for friendship. Warm, charismatic, genuinely sympathetic, and invariably thoughtful, she was the one who always remembered to ask the timely question, send the flowers, write the note. All year she kept an eye out for possible Christmas presents, so she could be sure of having just the right gift ready for each person on her long list. Stories abound of guests arriving for lunch or dinner at the White House and feeling desperately nervous until Eleanor, comfortable and welcoming, drew them into the room and put them at their ease.

What’s more, as she wrote in her memoir of the White House years, she was impressed early on by the awe and affection Americans felt when they visited 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, either as tourists or as invited guests. It was a powerful symbol not only of the nation, but of American hospitality, and she strongly believed that as First Lady she personified that hospitality. It’s hard to imagine that such a woman could read caustic newspaper stories about the terrible White House food and do nothing about it just because she cared more about unemployment. In truth, what was happening at the White House table didn’t reflect Eleanor’s disdain for food, it reflected a welter of complicated feelings about being First Lady at all—a job she had never wanted and the public face of a marriage that tormented her.

During FDR’s first term, Eleanor happened to read a popular new novel called Time Out of Mind, by Rachel Field. She was so taken by the portrait of the heroine that she wrote about the book in her syndicated column, “My Day.” The novel is set in a village on the coast of Maine, at the end of the 19th century, and features a woman whose crushing disappointments in love have left her profoundly detached not only from others, but from herself as well. In Eleanor’s words, the heroine is “absolutely self-forgetful,” as if her own humanity has fled. She puts in hours of hard, physical work each day and hopes to think of nothing else. “The description of the times when she tried to be just hands and feet, a mechanical automaton that moved and yet was numb, is very poignant,” Eleanor wrote. “For one reason or another, many of us can remember times like that in our lives.” Eleanor certainly could—the word “automaton” was one she used about herself more than once; and “times like that” extended over much of her life. It was during those times that she cultivated a detachment from the ordinary pleasures of eating and drinking. “How I wish I could enjoy food!” she cried out in a letter once. And yet she did enjoy food when the place and the people were right. They were never right in the White House.

__________________________________

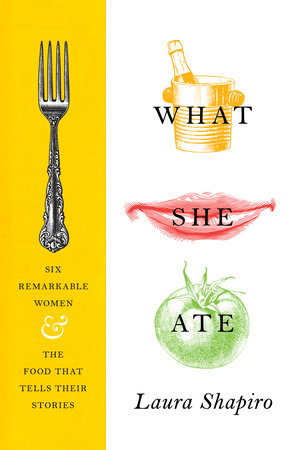

From What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories, by Laura Shapiro. Courtesy Viking, copyright 2017, Laura Shapiro.

Laura Shapiro

Laura Shapiro was an award-winning writer at Newsweek for more than fifteen years. Her articles have appeared in many publications, including The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Granta, and Gourmet. She is at work on a book about how women’s attitudes toward food in the late 1940s to early 60s presaged the cultural and culinary revolutions to come. She lives in New York City.