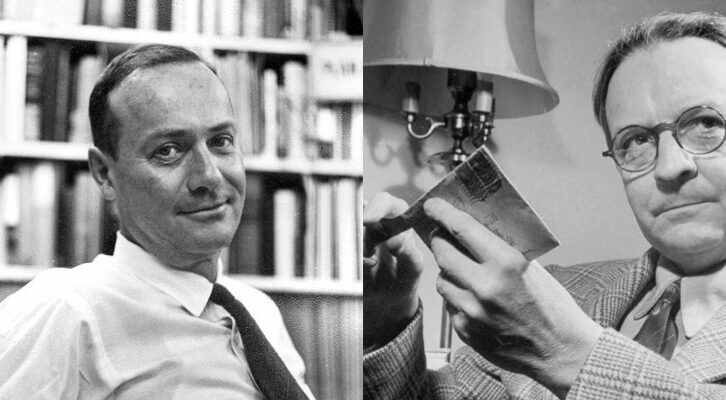

The Weird Stenographer: Sam Shepard on His Long Writing Life

RIP the Great American Playwright

Sam Shepard, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, actor, and American avant-garde icon died Thursday at his home in Kentucky from complications from Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 73. He often spoke of writing as his “salvation,” and if his prolific catalogue of work is to be believed, he sought that salvation constantly—and in turn, brought it to others with his moving, often surreal works of outcast art. Though famously hesitant to give interviews, he has, over the years, spoken in a number of places about his writing practice, the books he loved and authors who changed him, the life of the writer, and his relationship with literary inspiration. Here, I’ve collected some of his wisest and funniest words on the craft.

On what made him want to become a writer:

Oddly enough, it was reading Eugene O’Neill. I’d read Long Day’s Journey Into Night [1956], and I remember seeing Sidney Lumet’s black-and-white film adaptation [released in 1962], which I still think is one of the best adaptations of anything—of a book, of a play—ever done. . . But I remember being struck by the idea that it was a play, so I read the play and I read about O’Neill, and in an odd way, there was something that I connected with there . . . There was something wrong with the family. There was a demonic thing going on that nobody could put their finger on, but everybody knew the ship was sinking. Everybody was going down, and nobody knew why or how, and they were all taking desperate measures to stay afloat. So I thought there was something about that that felt similar to my own background, and I felt I could maybe write some version of that. (from an interview with Michael Almereyda in Interview, 2011)

On the very first thing he ever wrote:

I remember that when I was a kid, I wrote a story about a Coke bottle. You know that in the old days Coke bottles had the name of the city where they were manufactured inscribed on the bottom–St Paul, Dubuque, wherever. So I wrote this story about this bottle and its travels. It would get filled up in one town, some-one would drink it and throw it out the window, and then it would get on a truck and go somewhere else. (from an interview in Rolling Stone, 1986)

On finding his voice:

I’ve heard writers talk about ‘discovering a voice,’ but for me that wasn’t a problem. There were so many voices that I didn’t know where to start. It was splendid, really; I felt kind of like a weird stenographer. I don’t mean to make it sound like hallucination, but there were definitely things there, and I was just putting them down. I was fascinated by how they structured themselves, and it seemed like the natural place to do it was on a stage. A lot of the time when writers talk about their voice they’re talking about a narrative voice. For some reason my attempts at narrative turned out really weird. I didn’t have that kind of voice, but I had a lot of other ones, so I thought, Well, I’ll follow those. (from The Paris Review‘s The Art of Theater interview, 1997)

On writing like a rock star:

First off let me tell you that I don’t want to be a playwright. I want to be a rock and roll star. I want that understood right off. I got into writing plays because I had nothing else to do. So I started writing to keep from going off the deep end. That was back in ’64. Writing has become a habit. I like to yodel and dance and fuck a lot. Writing is neat because you do it on a very physical level. Just like rock and roll. A lot of people think playwrights are some special brand of intellectual fruit cake with special answers to special problems that confront the world at large. I think that’s a crock of shit. When you write a play you work out like a musician on a piece of music. You find all the rhythms and the melody and the harmonies and take them as they come. So much for theory. (from a 1971 biographical program note)

On the freedom of being a writer:

I feel very lucky and privileged to be a writer. I feel lucky in the sense that I can branch out into prose and tell different kinds of stories and stuff. But being a writer is so great because you’re literally not dependent on anybody. Whereas, as an actor, you have to audition or wait for somebody else to make a decision about how to use you, with writing, you can do it anywhere, anytime you want. You don’t have to ask permission. (from an interview with Michael Almereyda in Interview, 2011)

On writing his first novel:

After six book collections, basically I thought, ‘God, wouldn’t it be so great to be able to sustain something? . . . I don’t know how to explain it. I really don’t. Hopefully it’s a novel, but I have the hardest time sustaining prose. I feel like I’m a natural-born playwright but the prose thing has always mystified me. How to keep it going? . . . How do people do it, for years and years? I’ve been working on this for 10 years!” (from an interview in The Guardian, 2014)

On writing prose vs. writing plays:

You know, writing for the theatre is so different to writing for anything else. Because what you write is eventually going to be spoken. That’s why I think so many really powerful novelists can’t write a play—because they don’t understand that it’s spoken, that it hits the air. They don’t get that. . . But of course I have the opposite problem. . . I can hear language, I can hear it spoken out loud. But when it comes into the head I have a much harder time. (from an interview in The Guardian, 2014)

On the problem with American writers:

The thing about American writers is that as a group they get stuck in the same idea: that we’re a continent and the world falls away after us. And it’s just nonsense. . . We’re on our way out . . . Anybody that doesn’t realise that is looking like it’s Christmas or something. We’re on our way out, as a culture. America doesn’t make anything anymore! The Chinese make it! Detroit’s a great example. All of those cities that used to be something. If you go to a truck stop in Sallisaw, Oklahoma, you’ll probably see the face of America. How desperate we are. Really desperate. Just raw. (from an interview in The Guardian, 2014)

On Amiri Baraka and the state of experimental theater in the ’60s:

[T]heater seemed so far behind the other art forms, like jazz or Abstract Expressionism in painting or what they called “happenings” and the other kinds of experimentations that were taking place at that time. Theater still seemed to have this stilted, old-fashioned quality about it. So I couldn’t quite understand why theater, as a form, was spinning its wheels and not really going anywhere. Writers like LeRoi Jones . . . What’s his name now? Amiri Baraka . . . But back then he was LeRoi Jones, and he wrote some brilliant plays like The Toilet [1964] and Slave Ship [1969]. I think he was the most brilliant playwright of his era. And yet he was being overlooked as well. I don’t know what it was . . . It’s hard to say that it was because of the racial stuff . . . I thought his plays were far and away above anything else that was going on, even though there were other people struggling to do that sort of experimental work. . . I got to know LeRoi Jones, or Amiri Baraka, a little bit, and he was always sort of wary of me . . . But I thought he was a brilliant fucking writer—in prose and poetry as well. He’s overlooked in the scheme of things. He was angry . . . He was pissed. When I first met him, he was running around with an attaché case and a raincoat and was sort of neatly coifed and stuff. Then all of the sudden, he transformed into this revolutionary. (from an interview with Michael Almereyda in Interview, 2011)

On Roberto Bolaño and (not) belonging to a “brotherhood of writing”:

What I like most about Bolaño is his courage. . . In terms of what he’s writing about, how he’s doing it, and then, of course, the background of it all is that, at a certain point, he realized that he was terminally ill. He had this liver disease and, evidently, he was waiting for a transplant that came too late. But he never indulged in self-pity. I think there’s only one piece I’ve ever read about his illness directly. But it’s always in the background and, posthumously, we now understand that he was writing all this stuff while he was dying without indulging in that as a subject. . . I think Bolaño had a generosity about him that was unique. He seemed to include so many people in the circle of his adventures, whereas I felt like I was pretty selfish. When you get right down to it, I was only interested in these plays. And, of course, I did have some friends, but I don’t think I was as generous as Bolaño in his depiction of the people who influenced him and who he hung out with. I was never a part of any kind of literary club. I didn’t belong to any sort of brotherhood of writing, which Bolaño was always referring to. (from an interview with Michael Almereyda in Interview, 2011)

On Samuel Beckett:

He’s meant everything to me. He’s the first playwright—or the first writer, really—who just shocked me. It was like I didn’t know that kind of writing was possible. Similar to the experience of reading [Arthur] Rimbaud, it was like, “Where the fuck did he come up with this?” Of course, with Beckett, you can say it was [James] Joyce, because he’d worked for Joyce, but it was more than that. His trilogy of novels Molloy [1951], Malone Dies [1951], and The Unnamable [1953] are essentially monologues, and to see how he moved from those to plays . . . It was an absolutely seamless evolution. To me, with Waiting for Godot [1953], Endgame [1957], Krapp’s Last Tape [1958], and Happy Days [1961], he just gets better and better until he has just honed this thing . . .I suppose it was the form more than anything else that I was obsessed with, because I felt like the form of theater at the time was so retrograde. That’s what Joe Chaikin [the theater director] was after—this theme of naturalism that was so present was so old-fashioned and backward and unexpressive of the times. Theater needed a brave new kind of expression, and Beckett had invented a brand new form. (from an interview with Michael Almereyda in Interview, 2011)

On William Shakespeare:

I think there’s a big mystery about Shakespeare, but it’s too late to confirm it. I mean, look at the plays, the way they suddenly shift gears – from the earlier period to those later tragedies. Something happened that nobody knows about. I think he was involved in something deeply mysterious and esoteric, and at the time they had to keep it under wraps. There’s an awful lot of amazing insight in his plays that doesn’t come from an ordinary mind. And there was a tremendous monastic movement at that time. Who knows what he was into? (from an interview in Rolling Stone, 1986)

On his writing schedule:

When something kicks in, I devote everything to it and write constantly until it’s finished. But to sit down every day and say, I’m going to write, come hell or high water—no, I could never do that. . . There are certain attitudes that shut everything down. It’s very easy, for example, to get a bad attitude from a movie. I mean you’re trapped in a trailer, people are pounding on the door, asking if you’re ready, and at the same time you’re trying to write. . . . Film locations are a great opportunity to write. I don’t work on plays while I’m shooting a movie, but I’ve done short stories and a couple of novels. (from The Paris Review‘s The Art of Theater interview, 1997)

On the impact of drinking on his writing:

I didn’t feel like one inspired the other, or vice versa. I certainly never saw booze or drugs as a partner to writing. That was just the way my life was tending, you know, and the writing was something I did when I was relatively straight. I never wrote on drugs, or the bourbon. (from The Paris Review‘s The Art of Theater interview, 1997)

On the era when he didn’t rewrite:

Yes, when I was young and dumb, you know. Nineteen or twenty or something like that. I thought rewriting was against the law. (from an interview with GQ, 2012)

On why he won’t explain his own art:

[A]s soon as you start talking about your art and examining it and analyzing it, you kill it. You absolutely kill it. So I’m not going to do that. I’m not interested in putting it to death, you know? Once everyone is through, they’ll go, “Oh, now I get it.” They discard it. They throw it away. So long as they continue to question it, and so long as it continues to put them in the unknown and in the questioning mood, I think it has value. When they all of a sudden say, “Oh, I get it, I understand it, that’s what it’s all about,” you’re dead as an artist. Don’t you think? That’s why I will never write a memoir. (from an interview with GQ, 2012)

On waiting for inspiration to strike:

You wait, but you don’t wait too long, and then you pounce and sit right in the middle of it. I’m working on a monologue now. At the very beginning I thought, oh, if I wait a couple of days maybe more material will come. But I didn’t, and I’m glad. More material would have come, but I wouldn’t have written it down. (from an interview with The New York Times, 2016)

On the balance between craft and inspiration:

I don’t think you can have too much craft. Maybe you can’t have enough. It’s a funny balance between what we like to call inspiration and what we like to call work. And you can’t do without either one. If you hang around and wait for something to hit you in the head, you’re not going to write anything. You’ve got to work. You want to work for something. And these experiences, or accidents, can happen anytime. rough the back door.

For instance, I’ve been working on these stories, fiction, for some time, journals and whatnot, and I’ll be writing a while and take a look at something, and BOOM! there’s a play that’s developing while I’m working on short fiction, and I can’t not write it in that moment. I’ll think about all this time I’ve been spending working on this goddamn book, and then, what’s justified? (from an audience Q&A at the Cherry Lane Theater, 2006)

On how to tell when something is finished:

You write things in different states of mind. After a long day of writing, once you sleep on a story, that next morning isn’t the same as when you were engaged the previous night. You look at it later and realize it isn’t at all how you imagined it to be. So when you write a play ten years ago, and then come back to it, you’re a different person. So I think, Why not rewrite it in that new light? . . . The play has a rhythm. You gotta listen to it. You’ll know. (from an audience Q&A at the Cherry Lane Theater, 2006)

On endings:

I hate endings. Just detest them. Beginnings are definitely the most exciting, middles are perplexing and endings are a disaster. . . The temptation towards resolution, towards wrapping up the package, seems to me a terrible trap. Why not be more honest with the moment? The most authentic endings are the ones which are already revolving towards another beginning. That’s genius. Somebody told me once that fugue means to flee, so that Bach’s melody lines are like he’s running away. . . To me there’s something false about an ending. I mean, because of the nature of a play, you have to end it. People have to go home. (from The Paris Review‘s The Art of Theater interview, 1997)

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.