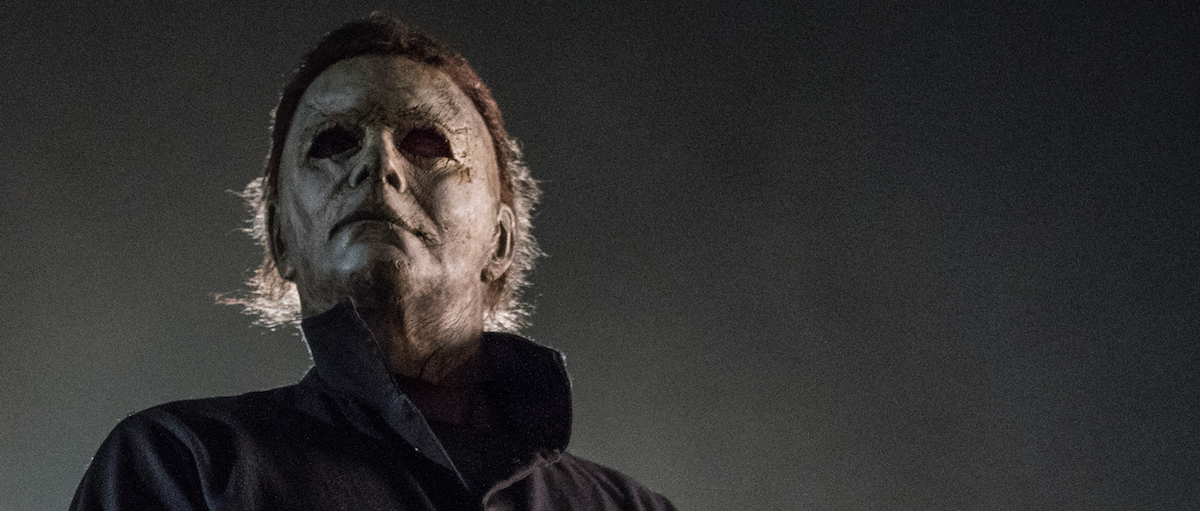

“I’ve seen enough horror movies to know any weirdo wearing a mask is never friendly,” Lizabeth Mott says in Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives. I imagine most of us have seen enough horror films to come to the same conclusion. The “weirdo wearing a mask” is perhaps the most recognizable trope in all of horror. Certainly this is true of the slasher subgenre: think of the hockey mask worn by Jason Voorhees in much of the Friday the 13th franchise or Leatherface’s multiple sewn-skin visages in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, think of the whitened William Shatner disguise that Michael Myers dons to do his dirty work in Halloween or the Munch-esque screaming face worn by the various Ghostface killers in the Scream film series.

Yet for all the mask’s prominence in horror cinema, it’s relatively rare for real world mass murderers and serial killers to wear masks in the commission of their ghastly crimes, so it’s strange that this has become such an iconic part of slasher lore. You might expect the actual instruments of murder to be the most terrifying elements of a scary movie, but at least as many viewers point to the villains’ masks as to their weapons when pinpointing the real root of their fear. Why might Jason’s goalie mask terrorize us more than his machete? Why might Michael’s blank, featureless façade instill more fear than his kitchen knife? Masks unsettle us because they force us to face fundamental metaphysical truths.

Throughout history, our ancestors have worn masks of one kind or another for the purposes of entertainment, mockery, ritual, protection, concealment, and transformation. A new face allows a person to take on a new role, to become someone else. Masks, in this way, have always been an essential part of our human need to play with identity. Their ability to promote this type of play—“playing pretend”—is contingent upon their capacity to disguise the wearer, conceal the face, and cloak what we suppose is the true self.

The mask acts as a barrier, a wall not only between us and him, but between us and understanding.In the most basic sense then, masks disturb us because they are, by definition, objects that cover all or part of the face, and facial recognition is a foundational aspect of generating human understanding and compassion. Our brains are specialized to recognize faces, analyze them for useful data, and empathize with them. We remember the faces of others much better than, say, their fingers, shoulders, or bellybuttons. We glean from a face much valuable information that can help us guess a person’s age, gender, race, nationality, health, economic status, psychological condition, emotional state, etc. We also communicate, commiserate, and connect through our faces. Thus, a person’s face becomes a synecdoche for the self.

Masking one’s face is a way to avoid being remembered, a way to refuse giving information, a way to eschew connection. Masks give the wearer the one thing we don’t want a killer to have: anonymity. If we can see his face, then there’s a chance we can empathize with him, encourage empathy in return, perhaps talk him out of the whole thing—and if we’re lucky enough to escape, seeing the perpetrator’s face would help us describe him to a police sketch artist or point him out in a line-up.

The mask acts as a barrier, a wall not only between us and him, but between us and understanding. Much of our fear comes from the fact that we don’t know—can’t know—who or what hides behind the mask. Indeed, in Friday the 13th: A New Beginning, the big reveal is that the man behind that film’s hockey mask isn’t Jason Voorhees at all, but a copycat killer. This conceit is played to horrifying effect in Tobe Hooper’s The Funhouse, where a strange man wanders a carnival in a Frankenstein’s Monster costume. When he is finally unmasked, what is revealed under the disguise is a nightmarish mutant face, so terrifying that the viewer almost longs for the comfort of the classic Universal creature’s green facial features. Here, the mask masks the true horror, an even more disturbing and unfathomable substrate; here, “horror is the removal of masks,” as Psycho author Robert Bloch claimed.

“A Man of Many Masks,” by James Ensor.

“A Man of Many Masks,” by James Ensor.

Though it is undeniably true that masks mask—that they promote concealment, performance, deception—there is another contradictory function of the mask. As Oscar Wilde famously declared, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Fernando Pessoa put it more poetically: “Masquerades disclose the reality of souls.” In other words, masks don’t merely conceal, they reveal. The mask may be a lie, but it is a lie that allows us to realize truth, to unveil reality, to disclose secrets, to perform honestly. In this “honest performance” paradox lies the truths of masks and metaphysics.

Not only does the mask paradoxically allow us to both play pretend and get at truth, but it manages to enact that underlying contradiction, revealing the lie as truth and the truth as lie. Identity, far from being an affinity, is a dance over an abyss. The chasm of self can only be crossed with an ever-expanding bridge of infinite masks.

The horror is the removal of masks because that which is under the mask is always another mask.“Every profound spirit needs a mask,” claimed Friedrich Nietzsche, “even more, around every profound spirit a mask is continually growing.” Our masks are not ours alone. They grow around us even when we don’t intentionally put them on. Others mask us as often as we mask ourselves—which is to say always. Without masks, we are shadows, dark shapes, bottomless pits—nothing more.

The best horror masks hint at this abyssal identity—in the holes of the one worn by Jason, in the nondescript blankness of the one worn by Michael, in the crude flesh collage-work of those worn by Leatherface. But this chasm of self can’t be glimpsed directly. Our proto-being (the us before the mask) is literally unthinkable, since the very act of thinking it masks it. If there can be no being that is not being-in-the-world, then there can be no being that is not being-with-a-mask.

Even a face, as Agatha Christie knew, “is, after all, nothing more nor less than a mask.” Thus, what we find in the removal of a mask, or in the revelation of anything properly hidden, is that the occulted world—that worm-infested earth beneath the deceptive topsoil—will remain occulted even in its exposure. The horror is the removal of masks because that which is under the mask is always another mask.

This played out in a particularly strange dream I had as a child, one spawned no doubt from watching too many episodes of Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! As a cartoon mystery built around characters who fear supernatural terrors, and with episodes that more often than not end with the unmasking of a disguised villain, Scooby-Doo is effectively introductory horror programming for children, initiating young viewers into the horror film’s macabre masquerade.

In the dream, my friends and I removed the mask from a bad guy we had caught red-handed. What we had caught him doing likely wasn’t important enough to register when I awoke, but if I did know then, I’ve long forgotten now. What followed, though, has been less easy to shake. In response to his unmasking, the man spoke some variation of that cartoon’s classic line, the one punctuating denouement of each episode: “And I would’ve gotten away with it, too, if it hadn’t been for you meddling kids!” But upon hearing that line, one of my friends began to pull at the villain’s face again—and it too proved to be a mask. Again and again, we would take turns pulling at his actual face, ripping at what seemed like flesh, only to discover another mask, ad infinitum.

What I knew then, without consciously realizing it, was that when it comes to identity, there is no outside mask. Everything is a mask, a series of masks, a swarm of simulacra with no referent reality. Infinite regress. Masks all the way down.

Ironically, then, the mask is itself the most honest face, because the mask admits its falsity. Jason Voorhees doesn’t need the hockey mask in order to conceal who he is; he needs it in order to reveal who he is. Likewise, Michael Myers doesn’t wear his white featureless mask to hide his identity; he wears it to reveal his identity—and, more generally, to reveal the masquerade that is the concept of identity itself.

If horror villains are emissaries from that occulted world, then their diplomatic mission isn’t merely one of death and destruction, but one of adumbration and revelation. They are here to shatter our reality, to confront us with the treachery of our images, to hew away at our meat and mechanisms in order to carve a space in our core, not so that something can fill it, but precisely so it can remain empty, so we can admit the internal void we avoid.

One of my favorite essays in the English language is “The Truth of Masks” by Oscar Wilde. In true mischievous Wildean fashion, the aesthete doesn’t use the word “masks” until the final line of the essay. His argument, put simply, is that Shakespeare paid close attention to the costuming of his plays, using dress as a means of producing certain dramatic effects. There is, according to Wilde, “no dramatist of the French, English, or Athenian stage who relies so much for his illusionist effects on the dress of his actors as Shakespeare does himself.” Yet after pages and pages arguing the importance of costumes in Shakespeare, the essay ends with the following sly admission:

Not that I agree with everything that I have said in this essay. There is much with which I entirely disagree. The essay simply represents an artistic standpoint, and in aesthetic criticism attitude is everything. For in art there is no such thing as a universal truth. A Truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true. And just as it is only in art-criticism, and through it, that we can apprehend the Platonic theory of ideas, so it is only in art-criticism, and through it, that we can realise Hegel’s system of contraries. The truths of metaphysics are the truths of masks.

On the one hand, this coda is what it claims to be on the surface: a moment where Wilde walks back his argument, admits he doesn’t entirely agree with the essay he has just written, is contradictory, even with himself. Yet this contrariness, this romantic irony, also manages to further his argument, completing the logic: costumes are crucial in Shakespeare because the truths of metaphysics are the truths of masks, because meaning is surface, illusion, fiction.

In the closing credits of Halloween, the killer is merely listed as “The Shape.” He is no longer Michael Myers. He exists as an outline, a silhouette, a body breathing through a mask—the occulted world in the shape of a man. And though we’re loathe to admit it, our outlines cut similar contours, for we are all vague shapes, all contrived masks. We are the mass of masked men and women in the finale of Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Face of Another. I am wearing a mask right now, and another beneath it—and another and another and another—just a stack of masks covering an abyss, moving forward, perpetually performing personas, even as I write these words. “Every surface is a cloak,” Nietzsche knew. “Every word also a mask.”

Thus, to borrow the words of René Descartes, “Masked, I advance,” from word to word, sentence to sentence, thought to thought, identity to identity, being to being, shape to shape.